NDEA Language and Area Centers: a Report on the First 5 Years. Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gelao Languages: Preliminary Classification and State of the Art Andrew Hsiu Center for Research in Computational Linguistics (CRCL), Bangkok, Thailand

The Gelao languages: Preliminary classification and state of the art Andrew Hsiu Center for Research in Computational Linguistics (CRCL), Bangkok, Thailand SEALS XXIII, May 2013 Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand Gelao’s position in Kra-Dai Kra-Dai (Tai-Kadai): primary branches Tai Hlai Ong Be Kam-Sui Kra Source: Ostapirat (2000) Goals of this talk Give a demographic overview of a little-known, but very important, language group Put together linguistics, anthropology, and history (mostly in Chinese) to get the “big picture” Propose a new preliminary internal classification of Gelao that takes recent data (post-2000) into account Explore some of Gelao’s interactions with neighboring languages Explain why Gelao is in urgent need of more scholarly attention Why Gelao? Why Gelao deserves much more attention in Kra-Dai studies: 1. Phylogenetic position: Divergent within KD 2. Internal diversity: Many distinct varieties, most likely around 10 languages (mutually unintelligible lects) 3. Historical importance: Major ethnic group in Chinese historical sources; known as Geliao 仡僚, etc. 4. Large present-day ethnic presence: Ethnic population of 500,000; speaker population: < 6,000. 5. Language endangerment: All Gelao varieties (except Central Gelao and Judu Gelao) are moribund with < 50 speakers left; fieldwork is extremely urgent. Internal diversity Gelao is by far the most internally diverse group of Kra languages. Remaining 3 Kra groups: relatively little internal variation – Buyang cluster (6 langs.): Paha, Ecun, Langjia, -

Even More Diverse Than We Had Thought: the Multiplicity of Trans-Fly Languages

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 5 (December 2012) Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century, ed. by Nicholas Evans and Marian Klamer, pp. 109–149 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp05/ 5 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4562 Even more diverse than we had thought: The multiplicity of Trans-Fly languages Nicholas Evans Australian National University Linguistically, the Trans Fly region of Southern New Guinea is one of the least known parts of New Guinea. Yet the glimpses we already have are enough to see that it is a zone with among the highest levels of linguistic diversity in New Guinea, arguably only exceeded by those found in the Sepik and the north coast. After surveying the sociocultural setting, in particular the widespread practice of direct sister-exchange which promotes egalitarian multilingualism in the region, I give an initial taste of what its languages are like. I focus on two languages which are neighbours, and whose speakers regularly intermarry, but which belong to two unrelated and typologically distinct families: Nen (Yam Family) and Idi (Pahoturi River Family). I then zoom out to look at some typological features of the whole Trans-Fly region, exemplifying with the dual number category, and close by stressing the need for documentation of the languages of this fascinating region. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 The distribution of linguistic diversity is highly informative, about 1 My thanks to two anonymous referees and to Marian Klamer for their usefully critical comments on an -

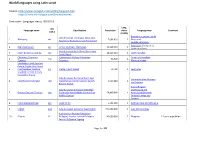

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

GERT OOSTINDIE Postcolonial Netherlands

amsterdam university press GERT OOSTINDIE Postcolonial Netherlands Sixty-five years of forgetting, commemorating, silencing Postcolonial Netherlands GERT OOSTINDIE Postcolonial Netherlands Sixty-five years of forgetting, commemorating, silencing amsterdam university press The publication of this book is made possible by a grant from Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research nwo( ). Original title: Postkoloniaal Nederland. Vijfenzestig jaar vergeten, herdenken, verdringen, Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, 2010 Translation: Annabel Howland Cover illustration: Netherlands East Indies Memorial, Amstelveen; photograph Eveline Kooijman Design: Suzan Beijer, Amersfoort isbn 978 90 8964 353 7 e-isbn 978 90 4851 402 1 nur 697 Creative Commons License CC BY NC (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) G.J. Oostindie / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2011 Some rights reversed. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 1 Decolonization, migration and the postcolonial bonus 23 From the Indies/Indonesia 26 From Suriname 33 From the Antilles 36 Migration and integration in the Netherlands -

LCSH Section T

T (Computer program language) T cell growth factor T-Mobile G1 (Smartphone) [QA76.73.T] USE Interleukin-2 USE G1 (Smartphone) BT Programming languages (Electronic T-cell leukemia, Adult T-Mobile Park (Seattle, Wash.) computers) USE Adult T-cell leukemia UF Safe, The (Seattle, Wash.) T (The letter) T-cell leukemia virus I, Human Safeco Field (Seattle, Wash.) [Former BT Alphabet USE HTLV-I (Virus) heading] T-1 (Reading locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell leukemia virus II, Human Safeco Park (Seattle, Wash.) BT Locomotives USE HTLV-II (Virus) The Safe (Seattle, Wash.) T.1 (Torpedo bomber) T-cell leukemia viruses, Human BT Stadiums—Washington (State) USE Sopwith T.1 (Torpedo bomber) USE HTLV (Viruses) t-norms T-6 (Training plane) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell receptor genes USE Triangular norms UF AT-6 (Training plane) BT Genes T One Hundred truck Harvard (Training plane) T cell receptors USE Toyota T100 truck T-6 (Training planes) [Former heading] USE T cells—Receptors T. rex Texan (Training plane) T-cell-replacing factor USE Tyrannosaurus rex BT North American airplanes (Military aircraft) USE Interleukin-5 T-RFLP analysis Training planes T cells USE Terminal restriction fragment length T-6 (Training planes) [QR185.8.T2] polymorphism analysis USE T-6 (Training plane) UF T lymphocytes T. S. Hubbert (Fictitious character) T-18 (Tank) Thymus-dependent cells USE Hubbert, T. S. (Fictitious character) USE MS-1 (Tank) Thymus-dependent lymphocytes T. S. W. Sheridan (Fictitious character) T-18 light tank Thymus-derived cells USE Sheridan, T. S. W. (Fictitious -

Languages of Indonesia (Papua)

Ethnologue report for Indonesia (Papua) Page 1 of 49 Languages of Indonesia (Papua) See language map. Indonesia (Papua). 2,220,934 (2000 census). Information mainly from C. Roesler 1972; C. L. Voorhoeve 1975; M. Donohue 1998–1999; SIL 1975–2003. The number of languages listed for Indonesia (Papua) is 271. Of those, 269 are living languages and 2 are second language without mother-tongue speakers. Living languages Abinomn [bsa] 300 (1999 Clouse and Donohue). Lakes Plain area, from the mouth of the Baso River just east of Dabra at the Idenburg River to its headwaters in the Foya Mountains, Jayapura Kabupaten, Mamberamo Hulu Kecamatan. Alternate names: Avinomen, "Baso", Foya, Foja. Dialects: Close to Warembori. Classification: Language Isolate More information. Abun [kgr] 3,000 (1995 SIL). North coast and interior of central Bird's Head, north and south of Tamberau ranges. Sorong Kabupaten, Ayamaru, Sausapor, and Moraid kecamatans. About 20 villages. Alternate names: Yimbun, A Nden, Manif, Karon. Dialects: Abun Tat (Karon Pantai), Abun Ji (Madik), Abun Je. Classification: West Papuan, Bird's Head, North-Central Bird's Head, North Bird's Head More information. Aghu [ahh] 3,000 (1987 SIL). South coast area along the Digul River west of the Mandobo language, Merauke Kabupaten, Jair Kecamatan. Alternate names: Djair, Dyair. Classification: Trans-New Guinea, Main Section, Central and Western, Central and South New Guinea-Kutubuan, Central and South New Guinea, Awyu-Dumut, Awyu, Aghu More information. Airoran [air] 1,000 (1998 SIL). North coast area on the lower Apauwer River. Subu, Motobiak, Isirania and other villages, Jayapura Kabupaten, Mamberamo Hilir, and Pantai Barat kecamatans. -

Number in Classifier Languages

Number in Classifier Languages A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Hiroki Nomoto IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Hooi Ling Soh March, 2013 c Hiroki Nomoto 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Acknowledgements Looking back at the years I spent for my doctoral studies, I cannot but realize that quite a number of people were there to play various roles. Most of them did not even know who I was, and I do not know who they were either, like those many strangers who said hi to me on the street, which by the way never happens at the places that I have lived other than in the United States. No matter how small their roles may be, they are definitely part of my memory and my life. Those who beat their collective power include the following individuals, to whom I wish to record my sincere gratitude here. The person who deserves the first mention is no one but my advisor, Hooi Ling Soh. If I had not met her in Singapore, my life—both academic and personal—would have been totally different. I greatly appreciate that she encouraged me to pursue my graduate studies at the Uni- versity of Minnesota (U of M). Though the decision making process was a painful experience, I strongly believe that I made the right decision. I have learned a lot through working with Hooi Ling. It is worth noting that my serious take on optionality and perspective towards it have developed in the course of our collaborative research on the verbal prefix meN- in Malay (Soh and Nomoto 2009, 2011, to appear). -

JSEALS Special Publication No

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 Papers from the Seventh International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics Edited by: Ring, Hiram <javascript:contributorCitation( ’Ring, Hiram’ );>; Rau, Felix <javascript:contributorCitation( ’Rau, Felix’ );> Abstract: This is a collection of 9 articles from the Seventh International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics held in 2017 in Kiel, Germany. The papers present significant advances in both diachronic and synchronic studies of Austroasiatic languages in Mainland Southeast Asia and Eastern India. Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-159822 Edited Scientific Work Published Version Originally published at: Papers from the Seventh International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics. Edited by: Ring, Hiram; Rau, Felix (2018). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. JSEALS Special Publication No. 3 PaPers from the SEVeNTH INterNatIoNal CoNFERENCe oN aUSTROASIATIC lINGUISTICs Edited by: Hiram Ring Felix Rau Copyright vested in the authors; Creative Commons Attribution Licence © 2018 University of Hawai’i Press All rights reserved OPEN ACCESS – Semiannual with periodic special publications E-ISSN: 1836-6821 http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52438 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. JSEALS publishes fully open access content, which means that all articles are available on the internet to all users immediately upon publication. Non-commercial use and distribution in any medium is permitted, provided the author and the journal are properly credited. Cover photo courtesy of Hiram Ring: Pnar speakers planting rice near Sohmynting, Meghalaya, North-East India. -

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum

Memoirs of the Queensland museum BRISBANE VOLUME 34 l March, 1994 Part 2 CUSTOMARY EXCHANGE ACROSS TORRES STRAIT DAVID LAWRENCE Lawrence, D. 1994:03 01: Customary exchange across Torres Strait Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 34(2):24l^46. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Customary exchange across Torres Strait is examined through a study of documentary sources, oral history and museum collections. The study includes an analysis of the material culture of exchange illustrating (he variety of artefacts of subsistence, ornamentation and dress, recreation, ceremony and dance, and warfare The idea that customary exchange across Torres Strait was a system of fixed, formalised, point-to-point trade routes is contested. This misconception, based on Haddon (1890, 1901-1935), McCarthy (1939) and Moore (1979), has arisen from reliance on historical documentary sources. By contrast, oral history from Torres Strait Islanders and coastal Papuans suggests that customary exchange was flexible and open, tied to changing social, political and cultural factors and operated within the framework of a dynamic Melancsian economic system. Customary exchange is re-evaluated and the paths and patterns of exchange are restructured. Panems of customary exchange formed as a result of separate linkages between individuals and groups and served to distribute scarce resources between the Islander, Papuan and Aboriginal peoples across <i region <>f considerable geographical, ecological and cultural diversity. Exchange is therefore interpreted in the context of the cultural and ecological discreteness of human groups within the Torres Strait region. This study also investigates the extent to which customary exchange exists in the contem- porary period and the implications of recent legal and administrative decisions such as the Torres Strait Treaty. -

How the Dutch Language Got Disseminated Into the World

国際政経論集(二松學舍大学)第 25 号,2019 年3月 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE (ARTICLES) How the Dutch Language Got Disseminated into the World Masako Nishikawa-Van Eester 西川(ヴァンエーステル)雅子 Samenvatting Dit artikel exploreert hoe het Nederlands verspreid werd in de wereld en welke invloed het had op de wereldgeschiedenis in het algemeen en op Japan in het bijzonder. Gedurende een zekere tijd waren Nederlands en Chinees de enige informatiekanalen aangaande de buitenwereld in Japan. Nederlands lag mee aan de basis van de modernisering van Japan in de 19de eeuw. De Nederlandse tolken/vertalers van toen werden opgevolgd door zij die Engels studeerden en die Japan verder op weg zetten om een moderne staat te worden. Verder werd Nederlands wereldwijd verspreid door de VOC (“Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie”). Vandaag nog zien we de overblijfselen daarvan in Suriname (Zuid-Amerika), Indonesië (Azië) en Zuid-Afrika (Afrika). De Nederlandse taal heeft duidelijk zijn steentje bijgedragen in het vormen van onze moderne samenleving. Abstract This article explores how the Dutch language spread into the world and how this fact influenced the world history thereafter, including the history of Japan. There was a period in Japan when Dutch and Chinese were the only information channels for the outer world. Dutch has given great influence on the dawn of the Japanese modernization in the 19th century. The Dutch translators/interpreters were succeeded by the English learners, who have propelled the development of Japan as a modern nation. Also, through the VOC, the East India Company, the Dutch language has spread its power and influence all over the world, and even today we see its remnants in Suriname in South America, Indonesia in Asia, and South Africa in Africa. -

Colleg3e of Arts and Sciences

COLLEGES OF' ARTS AND SCIENCE,S ·· Contents Colleges of Arts & Sciences .......................................... 86 Languages and Literatures of Europe and the Americas ............120 Degrees, Minors and Certifcates Offered ..................................87 Linguistics ................................................................................123 General nformation ..................................................................88 Second Language Studies ........................................................125 Accreditations and Affliations....................................................88 English Language nstitute....................................................128 Scholarships and Awards ...........................................................88 Hawaii English Language Program........................................128 A&S Honor Societies ..................................................................88 College of Natural Sciences .............................................129 Student Organizations ...............................................................88 Administration .........................................................................129 Undergraduate Programs ...........................................................88 College Certifcate ...................................................................129 Requirements for Undergraduate Degrees from the Colleges Mathematical Biology Undergraduate Certifcate ..................129 of Arts and Sciences ...............................................................88