Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

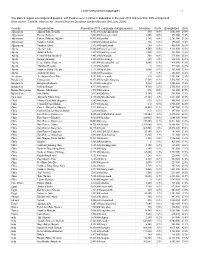

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Alfaz E Mewat's RJ Team Comprises A

VOL. 11 NO. 3 JANUARY 2014 www.civilsocietyonline.com .com/civilsocietyonline `50 broom as lightning rod AAAAAAPPP AAAnnnddd bbbeeeyyyooonnnddd ‘Laws aLone mewat’s feisty radio mobiLe Vaani taLks can’t stop Page 9 Pages 26-27 juggLing hiV numbers rise of cLean poLitics harassment’ Pages 10-11 Pages 29-30 Indira Jaising on the Justice Ganguly case and more a peopLe’s manifesto the other goa Pages 6-7 Pages 12-13 Pages 33-34 CONTENTs READ U S. WE READ YO U. the new politics s a magazine we have been keenly interested in efforts to clean up politics and improve governance. Our first issue, in september A2003, was on RTI and it had the then unknown Arvind Kejriwal on the cover. Our second issue, in October 2003, was about sheila Dikshit and how she was using RWAs to reach out to the middle class. Our third cover story, in November 2003, was titled ‘NGOs in Politics’ – it was about activists trying to influence politics and impact election outcomes. When we recall those issues, now 10 years old, we coVer story can’t help patting ourselves on the back. We had caught a trend much before anyone else had. The civil society aap and beyond space had begun taking shape in India and it was clear that important beginnings were being made in trans - The Aam Aadmi Party’s spectacular performance in Delhi heralds forming politics. Aruna Roy, Medha Patkar and a whole changing trends in Indian politics. Is this a movement or a party? lot of others were not only speaking for the weak and Is it a quick fix or a long-term solution? 20 powerless, but also trying to change the agendas of political parties. -

Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India

Chapter one: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India 1.1 Introduction: India also known as Bharat is the seventh largest country covering a land area of 32, 87,263 sq.km. It stretches 3,214 km. from North to South between the extreme latitudes and 2,933 km from East to West between the extreme longitudes. On this 2.4 % of earth‟s surface, lives 16% of world‟s population. With a population of 1,028,737,436 variations is there at every step of life. India is a land of bewildering diversity. India is bounded by the Indian Ocean on the Figure 1.1: India in World Population south, the Arabian Sea on the west and the Bay of Bengal on the east. Many outsiders explored India via these routes. The whole of India is divided into twenty eight states and seven union territories. Each state has its own cultural and linguistic peculiarities and diversities. This diversity can be seen in every aspect of Indian life. Whether it is culture, language, script, religion, food, clothing etc. makes ones identity multi-dimensional. Ones identity lies in his language, his culture, caste, state, village etc. So one can say India is a multi-centered nation. Indian multilingualism is unique in itself. It has been rightly said, “Each part of India is a kind of replica of the bigger cultural space called India.” (Singh U. N, 2009). Also multilingualism in India is not considered a barrier but a boon. 17 Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India Languages act as bridges because it enables us to know about others. -

Remaking of Meos Identity: an Analysis

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(3): 3711 -3724 ISSN: 00333077 Remaking of MEOs Identity: An Analysis Dr. Jai Kishan Bhardwaj Assistant Professor, Institute of Law, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra ABSTRACT The paper revolves around the issue of bargaining power. It is highlighted with the example of Meos of Mewat that the process of making of more Muslim identity of the poor, backward strata of Muslims i.e. of Meos is nothing but gaining of bargaining power by elitist Muslims. The going on process is continue even more dangerous today which was initiated mostly in 1920’s. How Hindu cadres were engaged in reconversion of Meos with the help of princely Hindu states of Alwar and Bharatpur in the leadership of Swami Shardhanand and Meos were taught about their glorious Hindu past. With the passage of time, Hindu efforts in the region proved to be short-lived but Islamic one i.e. Tablighi Jamaat still continues in its practice and they have been successful in their mission to a great extent. The process of Islamisation has affected the Meos identity at different levels. The paper successfully highlights how the Meo identity has shaped as Muslim identity with the passage of time. It is also pointed out that Indian Muslim identity has reshaped with the passage of time due to some factors. The author asserts that the assertion of religious identity in the process of democratisation and modernisation should be seen as a method by which deprived communities in a backward society seek to obtain a greater share of power, government jobs and economic resources. -

Data Source : Todd M. Johnson, Ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014)

Least evangelized megapeoples 1 The globe’s largest unevangelized peoples: 247 Peoples over 1 million in population in the year 2015 and less than 50% evangelized. Data source : Todd M. Johnson, ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014). Country People Name Population 2015 Language Autoglossonym Christians Chr% Evangelized Ev% Afghanistan Afghani Tajik (Tadzhik) 8,002,000 tajiki-afghanistan 800 0.0% 1,601,000 20.0% Afghanistan Hazara (Berberi) 2,604,000 hazaragi central 1,000 0.0% 574,000 22.0% Afghanistan Pathan (Pukhtun, Afghani) 11,995,000 pashto 2,400 0.0% 2,761,000 23.0% Afghanistan Southern Pathan 1,600,000 paktyan-pashto 320 0.0% 198,000 12.4% Afghanistan Southern Uzbek 2,590,000 özbek south 260 0.0% 466,000 18.0% Algeria Algerian Arab 23,684,000 jaza'iri general 9,500 0.0% 9,128,000 38.5% Algeria Arabized Berber 1,219,000 jaza'iri general 1,200 0.1% 544,000 44.6% Algeria Central Shilha (Beraber) 1,483,000 ta-mazight 300 0.0% 378,000 25.5% Algeria Hamyan Bedouin 2,836,000 hassaniyya 280 0.0% 582,000 20.5% Algeria Lesser Kabyle (Eastern) 1,002,000 tha-qabaylith east 5,000 0.5% 421,000 42.0% Algeria Shawiya (Chaouia) 2,129,000 shawiya 0 0.0% 479,000 22.5% Algeria Southern Shilha (Shleuh) 1,113,000 ta-shelhit 1,000 0.1% 363,000 32.6% Algeria Tajakant Bedouin 1,666,000 hassaniyya 0 0.0% 262,000 15.8% Azerbaijan Azerbaijani (Azeri Turk) 8,182,000 azeri north 820 0.0% 2,701,000 33.0% Bangladesh Chittagonian 13,475,000 bangla-chittagong 17,500 0.1% 5,542,000 41.1% Bangladesh Rangpuri (Rajbansi) 10,170,000 rajbangshi -

Abstract of Speakers' Strength of Languages and Mother Tongues - 2011

STATEMENT-1 ABSTRACT OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF LANGUAGES AND MOTHER TONGUES - 2011 Presented below is an alphabetical abstract of languages and the mother tongues with speakers' strength of 10,000 and above at the all India level, grouped under each language. There are a total of 121 languages and 270 mother tongues. The 22 languages specified in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India are given in Part A and languages other than those specified in the Eighth Schedule (numbering 99) are given in Part B. PART-A LANGUAGES SPECIFIED IN THE EIGHTH SCHEDULE (SCHEDULED LANGUAGES) Name of Language & mother tongue(s) Number of persons who Name of Language & mother tongue(s) Number of persons who grouped under each language returned the language (and grouped under each language returned the language (and the mother tongues the mother tongues grouped grouped under each) as under each) as their mother their mother tongue) tongue) 1 2 1 2 1 ASSAMESE 1,53,11,351 Gawari 19,062 Assamese 1,48,16,414 Gojri/Gujjari/Gujar 12,27,901 Others 4,94,937 Handuri 47,803 Hara/Harauti 29,44,356 2 BENGALI 9,72,37,669 Haryanvi 98,06,519 Bengali 9,61,77,835 Hindi 32,22,30,097 Chakma 2,28,281 Jaunpuri/Jaunsari 1,36,779 Haijong/Hajong 71,792 Kangri 11,17,342 Rajbangsi 4,75,861 Khari Boli 50,195 Others 2,83,900 Khortha/Khotta 80,38,735 Kulvi 1,96,295 3 BODO 14,82,929 Kumauni 20,81,057 Bodo 14,54,547 Kurmali Thar 3,11,175 Kachari 15,984 Lamani/Lambadi/Labani 32,76,548 Mech/Mechhia 11,546 Laria 89,876 Others 852 Lodhi 1,39,180 Magadhi/Magahi 1,27,06,825 4 DOGRI 25,96,767 -

Languages of India Being a Reprint of Chapter on Languages

THE LANGUAGES OF INDIA BEING A :aEPRINT OF THE CHAPTER ON LANGUAGES CONTRIBUTED BY GEORGE ABRAHAM GRIERSON, C.I.E., PH.D., D.LITT., IllS MAJESTY'S INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE, TO THE REPORT ON THE OENSUS OF INDIA, 1901, TOGETHER WITH THE CENSUS- STATISTIOS OF LANGUAGE. CALCUTTA: OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, INDIA. 1903. CALcuttA: GOVERNMENT OF INDIA. CENTRAL PRINTING OFFICE, ~JNGS STRERT. CONTENTS. ... -INTRODUCTION . • Present Knowledge • 1 ~ The Linguistio Survey 1 Number of Languages spoken ~. 1 Ethnology and Philology 2 Tribal dialects • • • 3 Identification and Nomenolature of Indian Languages • 3 General ammgemont of Chapter • 4 THE MALAYa-POLYNESIAN FAMILY. THE MALAY GROUP. Selung 4 NicobaresB 5 THE INDO-CHINESE FAMILY. Early investigations 5 Latest investigations 5 Principles of classification 5 Original home . 6 Mon-Khmers 6 Tibeto-Burmans 7 Two main branches 7 'fibeto-Himalayan Branch 7 Assam-Burmese Branch. Its probable lines of migration 7 Siamese-Chinese 7 Karen 7 Chinese 7 Tai • 7 Summary 8 General characteristics of the Indo-Chinese languages 8 Isolating languages 8 Agglutinating languages 9 Inflecting languages ~ Expression of abstract and concrete ideas 9 Tones 10 Order of words • 11 THE MON-KHME& SUB-FAMILY. In Further India 11 In A.ssam 11 In Burma 11 Connection with Munds, Nicobar, and !lalacca languages 12 Connection with Australia • 12 Palaung a Mon- Khmer dialect 12 Mon. 12 Palaung-Wa group 12 Khaasi 12 B2 ii CONTENTS THE TIllETO-BuRMAN SUll-FAMILY_ < PAG. Tibeto-Himalayan and Assam-Burmese branches 13 North Assam branch 13 ~. Mutual relationship of the three branches 13 Tibeto-H imalayan BTanch. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313,'761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9427804 The Gujars of Islamabad: A study in the social construction of local ethnic identities Spaulding, Frank Charles, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1994 Copyright ©1994 by Spaulding, Frank Charles. -

Some Areal Features of the 110-Item Wordlist for the Indo-Aryan Languages of South Odisha1

Anastasia Krylova Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences; [email protected] Some areal features of the 110-item wordlist 1 for the Indo-Aryan languages of South Odisha In this paper, I discuss the issue of replacement of basic lexicon due to language contact, spe- cifically focusing on Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, and Munda languages in South Odisha but with implications for Eastern India as a whole. Apart from direct borrowings, special attention is paid to cases of not particularly obvious substrate influence in Indo-Aryan languages, in which inherited lexicon is substituted by other inherited items as a result of semantic shift typical of a neighbouring language family. This type of phenomena should necessarily be taken into consideration in any quantitative studies involving lexicostatistical calculations. Keywords: Indo-Aryan languages; Dravidian languages; Munda languages; basic lexicon; lexicostatistics; areal linguistics. The aim of this study is to describe a number of specific features of the basic vocabulary con- tained in the 110-item Swadesh / Starostin / Yakhontov wordlists in the context of an entire lan- guage area (Sprachbund), primarily focusing on the data of the micro-language-area of South Od- isha (India) and its position within a larger area — East India as a whole (in the text below I shall refer to East India as a mini-area, since the term ‘area’ would be more suitable to de- scribe the entirety of South Asia as a whole). In these regions, three different language families are represented: Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, and Munda. Speakers of these languages are all set- tled in adjacent locations, where different language idioms mutually influence each other. -

Tokyo 2010 Handbook Contents

“All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” Matthew 28 :18-20 Tokyo2010 Global Mission Consultation Handbook Copyright © 2010 by Yong J. Cho All rights reserved No part of this handbook may be reproduced in any form without written permission, except in the case of brief quotation embodied in critical articles and reviews. Edited by Yong J. Cho and David Taylor Cover designed by Hyun Kyung Jin Published by Tokyo 2010 Global Mission Consultation Planning Committee 1605 E. Elizabeth St. Pasadena, CA 91104, USA 77-3 Munjung-dong, Songpa-gu, Seoul 138-200 Korea www.Tokyo2010.org [email protected] [email protected] Not for Sale Printed in the Republic of Korea designed Ead Ewha Hong TOKYO 2010 HANDBOOK CONTENTS Declaration (Pre-consultation Draft)ּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּ5 Opening Video Scriptּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּ8 Greetingsּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּ 11 Schedule and Program Overviewּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּ 17 Plenariesּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּּ -

WILDRE-2 2Nd Workshop on Indian Language Data

WILDRE2 - 2nd Workshop on Indian Language Data: Resources and Evaluation Workshop Programme 27th May 2014 14.00 – 15.15 hrs: Inaugural session 14.00 – 14.10 hrs – Welcome by Workshop Chairs 14.10 – 14.30 hrs – Inaugural Address by Mrs. Swarn Lata, Head, TDIL, Dept of IT, Govt of India 14.30 – 15.15 hrs – Keynote Lecture by Prof. Dr. Dafydd Gibbon, Universität Bielefeld, Germany 15.15 – 16.00 hrs – Paper Session I Chairperson: Zygmunt Vetulani Sobha Lalitha Devi, Vijay Sundar Ram and Pattabhi RK Rao, Anaphora Resolution System for Indian Languages Sobha Lalitha Devi, Sindhuja Gopalan and Lakshmi S, Automatic Identification of Discourse Relations in Indian Languages Srishti Singh and Esha Banerjee, Annotating Bhojpuri Corpus using BIS Scheme 16.00 – 16.30 hrs – Coffee break + Poster Session Chairperson: Kalika Bali Niladri Sekhar Dash, Developing Some Interactive Tools for Web-Based Access of the Digital Bengali Prose Text Corpus Krishna Maya Manger, Divergences in Machine Translation with reference to the Hindi and Nepali language pair András Kornai and Pushpak Bhattacharyya, Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization Niladri Sekhar Dash, Generation of a Digital Dialect Corpus (DDC): Some Empirical Observations and Theoretical Postulations S Rajendran and Arulmozi Selvaraj, Augmenting Dravidian WordNet with Context Menaka Sankarlingam, Malarkodi C S and Sobha Lalitha Devi, A Deep Study on Causal Relations and its Automatic Identification in Tamil Panchanan Mohanty, Ramesh C. Malik & Bhimasena Bhol, Issues in the Creation of Synsets in Odia: A Report1 Uwe Quasthoff, Ritwik Mitra, Sunny Mitra, Thomas Eckart, Dirk Goldhahn, Pawan Goyal, Animesh Mukherjee, Large Web Corpora of High Quality for Indian Languages i Massimo Moneglia, Susan W. -

'It Is a Dialect, Not a Language!'— Investigating

‘IT IS A DIALECT, NOT A LANGUAGE!’— INVESTIGATING TEACHERS’ BELIEFS ABOUT MEWATI PRERNA BAKSHI The Education University of Hong Kong Abstract There is a paucity of research on dialect awareness among teachers, particularly in South Asia. This paper investigates teachers’ beliefs about Mewati, a vernacular language variety spoken by the Meo people living in Haryana, India. Data was collected primarily through detailed semi-structured interviews from local native Mewati speaking Meo and non-Meo teachers working in rural government and urban private schools. Nearly all teachers expressed unfavourable beliefs towards Mewati and discouraged its use in the classroom. This despite teachers candidly admitting students struggle, often as late as the eighth grade, with the standard language(s) of Hindi and/or English adopted as the medium of instruction. View- ing this as a rite of passage all students must go through, teachers normalized the status quo by calling it a ‘natural’ and ‘transitory’ phase. This article argues, however, that these teachers’ beliefs and practices leave students struggling for far too long during their crucial years of learning and development. 50% of students leave school before reaching the eighth grade in India (UNICEF, 2005). These high dropout rates found across Mewat and India more generally could partly be explained by student alienation. Part of this alienation is a result of disregarding students’ first languages which are stigmatized as ‘dialects’. Keywords: language policy, language ideology, language attitude, teachers’ beliefs, mother tongue 1 Bakshi, P. (2020). ‘It is a dialect, not a language!’—Investigating teachers’ beliefs about Me- wati. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 20, 1-24.