Analysis of Mode Locking and Ultrashort Laser Pulses with a Nonlinear Refractive Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self Amplified Lock of a Ultra-Narrow Linewidth Optical Cavity

Self Amplified Lock of a Ultra-narrow Linewidth Optical Cavity Kiwamu Izumi,1, ∗ Daniel Sigg,1 and Lisa Barsotti2 1LIGO Hanford Observatory, PO Box 159 Richland, Washington 99354, USA 2LIGO laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachussetts 02139, USA compiled: January 8, 2016 High finesse optical cavities are an essential tool in modern precision laser interferometry. The incident laser field is often controlled and stabilized with an active feedback system such that the field resonates in the cavity. The Pound-Drever-Hall reflection locking technique is a convenient way to derive a suitable error signal. However, it only gives a strong signal within the cavity linewidth. This poses a problem for locking a ultra-narrow linewidth cavity. We present a novel technique for acquiring lock by utilizing an additional weak control signal, but with a much larger capture range. We numerically show that this technique can be applied to the laser frequency stabilization system used in the Laser Interferometric Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) which has a linewidth of 0.8 Hz. This new technique will allow us to robustly and repeatedly lock the LIGO laser frequency to the common mode of the interferometer. OCIS codes: (140.3425), (140.3410) http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/XX.99.099999 High finesse optical cavities have been an indispens- nonlinear response [8, 9] dominant and thus hinder the able tool for precision interferometry to conduct rela- linear controller. tivistic experiments such as gravitational wave detection Gravitational wave observatories deploy kilometer [1{3] and optical clocks [4]. The use of a high finesse cav- scale interferometers with extremely narrow linewidth. -

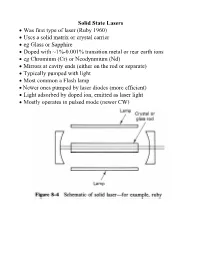

(Ruby 1960) • Uses a Solid Matrix Or Crystal Carrier • Eg Glass Or Sapphire

Solid State Lasers • Was first type of laser (Ruby 1960) • Uses a solid matrix or crystal carrier • eg Glass or Sapphire • Doped with ~1%-0.001% transition metal or rear earth ions • eg Chromium (Cr) or Neodynmium (Nd) • Mirrors at cavity ends (either on the rod or separate) • Typically pumped with light • Most common a Flash lamp • Newer ones pumped by laser diodes (more efficient) • Light adsorbed by doped ion, emitted as laser light • Mostly operates in pulsed mode (newer CW) Flash Lamp Pumping • Use low pressure flash tubes (like electronic flash) • Xenon or Krypton gas at a few torr (mm of mercury pressure) • Electrodes at each end of tube • Charge a capacitor bank: 50 - 2000 µF, 1-4 kV • High Voltage pulse applied to tube • Ionizes part of gas • Makes tube conductive • Capacitor discharges through tube • Few millisec. pulse • Inductor slows down discharge Light Source Geometry • Earlier spiral lamp: inefficient but easy • Now use reflectors to even out light distribution • For CW operation use steady light sources Tungsten Halogen or Mercury Vapour • Use air or water cooling on flash lamps Q Switch Pulsing • Most solid states use Q switching to increase pulse power • Block a cavity with controllable absorber or switch • Acts like an optical switch • During initial pumping flash pulse switch off • Recall the Quality Factor of resonance circuits (eg RLC) 2π energy stored Q = energy lost per light pass • During initial pulse Q low • Allows population inversion to increase without lasing • No stimulated emission • Then turn switch on -

Power Build-Up Cavity Coupled to a Laser Diode

I POWER BUILD-UP CAVITY COUPLED I TO A LASER DIODE Daniel J. Evans I Center of Excellence for Raman Technology University of Utah I Abstract combination of these elements will emit photons at different frequencies. The ends of these semiconductor In many Raman applications there is a need to devices are cleaved to form mirrors that bounce the I detect gases in the low ppb range. The desired photons back and forth within the cavity. The photons sensitivity can be achieved by using a high power laser excite more electrons, which form more photons source in the range of tens of watts. A system (referred to as optical pumping). 2 A certain portion of I combining a build-up cavity to enhance the power and the photons emit through the front and back cleaved an external cavity laser diode setup to narrow the surfaces of the laser diode. The amount of photons that bandwidth can give the needed power to the Raman get through the cleaved surfaces can be adjusted by I spectroscopy system. coating the surface or installing other mirrors. Introduction to Laser Diodes The planar cleaved surfaces of the laser diode form a Fabry-Perot cavity with set resonance frequencies I An important characteristic of all lasers is the (vp).3 The typical laser diode has a spacing of 150 f.1I11 mode structure. The mode structure refers to both the with an index of refraction of 3.5, yielding a resonance lasing frequency and the spatial characteristics of the frequency of 285 GHz. The wavelength spacing (~A.) I laser. -

Quantum Illumination at the Microwave Wavelengths

Quantum Illumination at the Microwave Wavelengths 1 2 3 4 5 6, Shabir Barzanjeh, Saikat Guha, Christian Weedbrook, David Vitali, Jeffrey H. Shapiro, and Stefano Pirandola ∗ 1Institute for Quantum Information, RWTH Aachen University, 52056 Aachen, Germany 2Quantum Information Processing Group, Raytheon BBN Technologies, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA 3QKD Corp., 60 St. George St., Toronto, M5S 3G4, Canada 4School of Science and Technology, University of Camerino, Camerino, Macerata 62032, Italy 5Research Laboratory of Electronics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA 6Department of Computer Science & York Centre for Quantum Technologies, University of York, York YO10 5GH, United Kingdom Quantum illumination is a quantum-optical sensing technique in which an entangled source is exploited to improve the detection of a low-reflectivity object that is immersed in a bright thermal background. Here we describe and analyze a system for applying this technique at microwave frequencies, a more appropriate spectral region for target detection than the optical, due to the naturally-occurring bright thermal background in the microwave regime. We use an electro-opto- mechanical converter to entangle microwave signal and optical idler fields, with the former being sent to probe the target region and the latter being retained at the source. The microwave radiation collected from the target region is then phase conjugated and upconverted into an optical field that is combined with the retained idler in a joint-detection -

Construction of a Flashlamp-Pumped Dye Laser and an Acousto-Optic

; UNITED STATES APARTMENT OF COMMERCE oUBLICATION NBS TECHNICAL NOTE 603 / v \ f ''ttis oi Construction of a Flashlamp-Pumped Dye Laser U.S. EPARTMENT OF COMMERCE and an Acousto-Optic Modulator National Bureau of for Mode-Locking Iandards — NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS 1 The National Bureau of Standards was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measure- ment system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Center for Computer Sciences and Technology, and the Office for Information Programs. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consistent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scien- tific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of a Center for Radia- tion Research, an Office of Measurement Services and the following divisions: Applied Mathematics—Electricity—Heat—Mechanics—Optical Physics—Linac Radiation 2—Nuclear Radiation 2—Applied Radiation 2—Quantum Electronics 3— Electromagnetics 3—Time and Frequency 3 —Laboratory Astrophysics3—Cryo- 3 genics . -

Ophthalmic Laser Therapy: Mechanisms and Applications

1 Ophthalmic Laser Therapy: Mechanisms and Applications Daniel Palanker Department of Ophthalmology and Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, CA Definition The term LASER is an abbreviation which stands for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The laser is a source of coherent, directional, monochromatic light that can be precisely focused into a small spot. The laser is a very useful tool for a wide variety of clinical diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Principles of Light Emission by Lasers Molecules are made up of atoms, which are composed of a positively charged nucleus and negatively charged electrons orbiting it at various energy levels. Light is composed of individual packets of energy, called photons. Electrons can jump from one orbit to another by either, absorbing energy and moving to a higher level (excited state), or emitting energy and transitioning to a lower level. Such transitions can be accompanied by absorption or spontaneous emission of a photon. “Stimulated Emission” is a process in which photon emission is stimulated by interaction of an atom in excited state with a passing photon. The photon emitted by the atom in this process will have the same phase, direction of propagation and wavelength as the “stimulating photon”. The “stimulating photon” does not lose energy during this interaction- it simply causes the emission and continues on, as illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1: LASER: Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation For such stimulated emission to occur more frequently than absorption (and hence result in light amplification), the optical material should have more atoms in excited state than in a lower state. -

Generation of a Flat-Top Laser Beam for Gravitational Wave Detectors By

Generation of a flat-top laser beam for gravitational wave detectors by means of a nonspherical Fabry–Perot resonator Marco G. Tarallo,1,2,* John Miller,2,3 J. Agresti,1,2 E. D’Ambrosio,2 R. DeSalvo,2 D. Forest,4 B. Lagrange,4 J. M. Mackowsky,4 C. Michel,4 J. L. Montorio,4 N. Morgado,4 L. Pinard,4 A. Remilleux,4 B. Simoni,1,2 and P. Willems2 1Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Pisa, Largo Pontecorvo 3, 56100 Pisa, Italy 2LIGO Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Boulevard, Pasadena, California, USA 3Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK 4Laboratoire des Matèriaux Avancès, 22 Boulevard Niels Bohr, Villeurbanne, France *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received 23 February 2007; revised 6 July 2007; accepted 11 July 2007; posted 13 July 2007 (Doc. ID 80265); published 7 September 2007 We have tested a new kind of Fabry–Perot long-baseline optical resonator proposed to reduce the thermal noise sensitivity of gravitational wave interferometric detectors—the “mesa beam” cavity—whose flat top beam shape is achieved by means of an aspherical end mirror. We present the fundamental mode intensity pattern for this cavity and its distortion due to surface imperfections and tilt misalignments, and contrast the higher order mode patterns to the Gauss–Laguerre modes of a spherical mirror cavity. We discuss the effects of mirror tilts on cavity alignment and locking and present measurements of the mesa beam tilt sensitivity. © 2007 Optical Society of America OCIS codes: 140.4780, 120.2230, 230.0040. -

3-5 Development of an Ultra-Narrow Line-Width Clock Laser

3-5 Development of an Ultra-Narrow Line-Width Clock Laser LI Ying, NAGANO Shigeo, MATSUBARA Kensuke, KOJIMA Reiko, KUMAGAI Motohiro, ITO Hiroyuki, KOYAMA Yasuhiro, and HOSOKAWA Mizuhiko An optical lattice clock and a single ion optical clock are being developed in National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT). Diode lasers are used for the develop- ment of extremely narrow linewidth clock lasers for optical frequency standards. Using the Pound- Drever-Hall technique, the required reduction of linewidth was achieved by locking the laser to an ultrahigh-fi nesse ultralow-expansion glass (ULE) reference cavity, which is set in the high vacuum chamber with a constant temperature and isolated against environmental noise and vibration. As a result, the laser linewidth is decreased down to several Hz. The Allan deviation is less than 4×10−15 at an averaging time over 100 s. A vibration-insensitive optical cavity has been designed, aiming the linewidth below 1 Hz. In this chapter, we report the present status of development of the clock lasers at NICT. Keywords Laser frequency stabilization, Diode laser, Optical reference cavity, Optical clock, Optical frequency standard 1 Introduction an uncertainty of 10−17 or less is divided into two types. The fi rst is the “optical lattice The second, the current time and frequency clock” [4] [5], neutral atoms are trap in the opti- standard unit, is defi ned according to the hy- cal lattice “magic wave length” and the second perfi ne structure transition of cesium atoms by is the “single ion clock” [6], single ion is con- the General Conference of Weights and Mea- fi ned to the Lamb-Dick regime. -

Main Requirements of the Laser • Optical Resonator Cavity • Laser

Main Requirements of the Laser • Optical Resonator Cavity • Laser Gain Medium of 2, 3 or 4 level types in the Cavity • Sufficient means of Excitation (called pumping) eg. light, current, chemical reaction • Population Inversion in the Gain Medium due to pumping Laser Types • Two main types depending on time operation • Continuous Wave (CW) • Pulsed operation • Pulsed is easier, CW more useful Optical Resonator Cavity • In laser want to confine light: have it bounce back an forth • Then it will gain most energy from gain medium • Need several passes to obtain maximum energy from gain medium • Confine light between two mirrors (Resonator Cavity) Also called Fabry Perot Etalon • Have mirror (M1) at back end highly reflective • Front end (M2) not fully transparent • Place pumped medium between two mirrors: resonator • Curved mirror will focus beam approximately at radius • However is the resonator stable? • Stability given by g parameters: g1 back mirror, g2 front mirror: L gi = 1 − ri • For two mirrors resonator stable if 0 < g1g2 < 1 • unstable if g1g2 < 0 g1g2 > 1 • at the boundary (g1g2 = 0 or 1) marginally stable Stability of Different Resonators Polarization and Lasers • Lasers often need output windows on gain medium in cavity • Output windows often produce polarized light • Polarized means light's electric and magnetic vectors at a particular angle • Normal windows lose light to reflection • Least loss for windows if light hits glass at Brewster Angle • Perpendicular polarization reflected • Parallel polarization transmitted with -

CRDS) Work? CRDS: a Technology That Can Assess the Amount of Molecules in the Air by Measuring the Molecular Absorption of Laser Light in an Optical Cavity

What Makes Cavity Ringdown Spectroscopy (CRDS) Work? CRDS: A technology that can assess the amount of molecules in the air by measuring the molecular absorption of laser light in an optical cavity. Light (photons) and Molecules Molecules can absorb light and get “excited” at special frequencies. hν CH4 molecule These special frequencies are molecule specific. H H f = special frequencies 1 k k= spring constant C f = 2π m m = mass H H Each type of molecule absorb light only at its special frequencies. Light is absorbed at special frequencies specific to each molecule. hν 1 k f = Detector π absorption 2 m Ethylene, C2O2 Methane hν hν’ Ethylene Detector absorption wavelength Methane, CH4 At these special frequencies, the greater the distance the light travels through the sample the greater the total absorption. short hν’ Detector absorption Same number of molecules per unit volume wavelength hν’ Detector absorption Long wavelength CRDS’s optical cavity transforms 45,000 ft (8.5 miles) into 22,500 round trips in a ~1 ft long sample cell. High Reliability Laser Frequency Meter Pressure Gauge Outlet Gas Flow Temperature Gauge (to pump) Sample Gas Inlet Photo Detector Three Mirror Optical Cavity ~1 ft Resulting in parts-per-billion sensitivity Control of these four factors make CRDS ideally suited to perform scientific and industrial measurements all over the world. • Detecting low levels of trace gases • Measuring small changes in the concentration of gases • Ensuring measurement accuracy • Ensuring long-term reliability of the measurement Aircraft -

Holmium-Co-Doped Fiber Lasers Using MAX Phase (Ti3alc2) H

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Generation of Q-switched Pulses in Thulium-doped and Thulium/ Holmium-co-doped Fiber Lasers using MAX phase (Ti3AlC2) H. Ahmad1,2 ✉ , A. A. Kamely1, N. Yusof1, L. Bayang1 & M. Z. Samion1 A MAX phase Ti3AlC2 thin flm is demonstrated as a saturable absorber (SA) to induce Q-switching in the 2.0 μm region. The Ti3AlC2 thin flm is sandwiched between two fber ferrules and integrated into thulium doped fber laser (TDFL) and thulium-holmium doped fber laser (THDFL) cavities. Stable Q-switched pulses are observed at 1980.79 nm and 1959.3 nm in the TDFL and THDFL cavities respectively, with repetition rates of 32.57 kHz and 21.94 kHz and corresponding pulse widths of 2.72 μs and 3.9 μs for both cavities. The performance of the Ti3AlC2 based SA for Q-switching operation indicates the high potential of other MAX phase materials to serve as SAs in future photonics systems. Q-switched fber lasers are highly desired laser sources for a wide number of applications due to their potential to produce high energy pulses for use in applications such as sensors1, micromachining2,3 and medical systems4–6. Recently, Q-switching in the 2 micron region has received increasing interest due to its various applications such as optical communications7, remote sensing8 and in particular for biological and medical applications9. Q-switched lasers operating at 2.0 µm have been demonstrated for various applications such as the treatment of skin discoloration due to melasma pigmentation10–12 by multiple passes with a large spot size laser13, as well as for the removal of tattoos14–19. -

A History of High-Power Laser Research and Development in the United Kingdom

High Power Laser Science and Engineering, (2021), Vol. 9, e18, 86 pages. doi:10.1017/hpl.2021.5 REVIEW A history of high-power laser research and development in the United Kingdom Colin N. Danson1,2,3, Malcolm White4,5,6, John R. M. Barr7, Thomas Bett8, Peter Blyth9,10,11,12, David Bowley13, Ceri Brenner14, Robert J. Collins15, Neal Croxford16, A. E. Bucker Dangor17, Laurence Devereux18, Peter E. Dyer19, Anthony Dymoke-Bradshaw20, Christopher B. Edwards1,14, Paul Ewart21, Allister I. Ferguson22, John M. Girkin23, Denis R. Hall24, David C. Hanna25, Wayne Harris26, David I. Hillier1, Christopher J. Hooker14, Simon M. Hooker21, Nicholas Hopps1,17, Janet Hull27, David Hunt8, Dino A. Jaroszynski28, Mark Kempenaars29, Helmut Kessler30, Sir Peter L. Knight17, Steve Knight31, Adrian Knowles32, Ciaran L. S. Lewis33, Ken S. Lipton34, Abby Littlechild35, John Littlechild35, Peter Maggs36, Graeme P. A. Malcolm OBE37, Stuart P. D. Mangles17, William Martin38, Paul McKenna28, Richard O. Moore1, Clive Morrison39, Zulfikar Najmudin17, David Neely14,28, Geoff H. C. New17, Michael J. Norman8, Ted Paine31, Anthony W. Parker14, Rory R. Penman1, Geoff J. Pert40, Chris Pietraszewski41, Andrew Randewich1, Nadeem H. Rizvi42, Nigel Seddon MBE43, Zheng-Ming Sheng28,44, David Slater45, Roland A. Smith17, Christopher Spindloe14, Roy Taylor17, Gary Thomas46, John W. G. Tisch17, Justin S. Wark2,21, Colin Webb21, S. Mark Wiggins28, Dave Willford47, and Trevor Winstone14 1AWE Aldermaston, Reading, UK 2Oxford Centre for High Energy Density Science, Department of Physics,