Energy Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Energy Use and Environmental Effects of Electric Vehicles

Article Primary Energy Use and Environmental Effects of Electric Vehicles Efstathios E. Michaelides Department of Engineering, TCU, Fort Worth, TX 76132, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The global market of electric vehicles has become one of the prime growth industries of the 21st century fueled by marketing efforts, which frequently assert that electric vehicles are “very efficient” and “produce no pollution.” This article uses thermodynamic analysis to determine the primary energy needs for the propulsion of electric vehicles and applies the energy/exergy trade-offs between hydrocarbons and electricity propulsion of road vehicles. The well-to-wheels efficiency of electric vehicles is comparable to that of vehicles with internal combustion engines. Heat transfer to or from the cabin of the vehicle is calculated to determine the additional energy for heating and air-conditioning needs, which must be supplied by the battery, and the reduction of the range of the vehicle. The article also determines the advantages of using fleets of electric vehicles to offset the problems of the “duck curve” that are caused by the higher utilization of wind and solar energy sources. The effects of the substitution of internal combustion road vehicles with electric vehicles on carbon dioxide emission avoidance are also examined for several national electricity grids. It is determined that grids, which use a high fraction of coal as their primary energy source, will actually increase the carbon dioxide emissions; while grids that use a high fraction of renewables and nuclear energy will significantly decrease their carbon dioxide emissions. Globally, the carbon dioxide emissions will decrease by approximately 16% with the introduction of electric vehicles. -

2017 2030 a Forward Looking Primary Energy Factor for A

A forward looking Primary Energy Factor for a greener European Future What is the Primary Energy Factor and why does it exist? The Primary Energy Factor (PEF) connects primary and final energy. It indicates how much primary energy is used to generate a unit of electricity or a unit of useable thermal energy. It allows for comparison between the primary energy consumption of products with the same functionality (e.g. heating) using different energy carriers (particularly electricity vs. fossil fuels). Electricity is a final energy carrier, produced from different primary energy sources like fossil fuels (gas, coal), nuclear and renewables (hydro, wind, solar). Currently a PEF of 2.5 is used as a “conversion factor" to express electricity consumption/savings in primary energy consumption/savings, regardless of the type of energy source used to produce it (also when the electricity comes from renewables). The current conversion factor implies that 1 unit of electricity requires an input of 2.5 units of primary energy. This assumes all power generation in the EU to have a 40% efficiency (100 / 2.5 = 40) – even non-dispatchable renewables from which energy is harnessed without the combustion of fuel. A PEF of 2.5 is too high and does not reflect the reality of power generation. The need to update the PEF to 2.0 The Commission has decided to review the PEF value and methodology in the Energy Efficiency Directive to better reflect the EU energy mix, in particular today’s share of renewable energy in electricity generation and its strong increase in the near future . -

Total Energy Consumption by Fuel, EU-27

EN26 Total Primary Energy Consumption by Fuel Key message Fossil fuels continue to dominate total energy consumption, but environmental pressures have been reduced, partly due to a significant switch from coal and lignite to relatively cleaner natural gas in the 1990s. The share of renewable energy sources remains small despite an increase in absolute terms. Overall, total primary energy consumption increased by an average of 0.6 % per annum during the period 1990-2005 (9.8 % overall) thus counteracting some of the environmental benefits from fuel switching. Rationale The indicator provides an indication of the environmental pressures originating from energy consumption. The environmental impacts such as resource depletion, greenhouse gas emissions, air pollutant emissions and radioactive waste generation strongly depend on the type and amount of fuel consumed. Fig. 1: Total energy consumption by fuel, EU-27 1800 1600 1400 1200 Renewables Nuclear 1000 Coal and lignite Gas 800 Oil 600 400 Million tonnes of oil equivalents 200 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Data source: EEA, Eurostat (historic data) 1. Indicator assessment Total primary energy consumption in the EU-27 increased by 9.8 % between 1990 and 2005. Over the same period, the share of fossil fuels, including coal, lignite, oil and natural gas, in primary energy consumption declined slightly from 83 % in 1990 to 79.0 % in 2005, although fossil fuel consumption increased in absolute terms (by more than 4 %). The use of fossil fuels has considerable impact on the environment and is the main cause of greenhouse gas emissions. -

History of Energy

CONCISE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORY OF ENERGY Editor C. CLEVELAND Boston University, Boston, MA, USA ELSEVIER Amsterdam—Boston—Heidelberg—London—New York—Oxford Paris—San Diego—San Francisco—Singapore—Sydney—Tokyo CONTENTS Editor's Preface vii Alphabetical List of Articles ix c Coal Industry, History of Jaak J K Daemen 1 Coal Mining in Appalachia, History of Geoffrey L Buckley 17 Conservation Measures for Energy, History of John H Gibbons, Holly L Gwin 27 Conservation of Energy Concept, History of Elizabeth Garber 36 E Early Industrial World, Energy Flow in Richard D Periman 45 Economic Thought, History of Energy in Paul Christensen 53 Ecosystems and Energy: History and Overview Charles AS Hall 65 Electricity Use, History of David E Nye 77 Energy in the History and Philosophy of Science Robert P Crease 90 Environmental Change and Energy 1 G Simmons 94 F Fire: A Socioecological and Historical Survey Johan Goudsblom 105 G Geographic Thought, History of Energy in Barry D Solomon, Martin J pasqualetti 117 H Hydrogen, History of Seth Dunn 127 Hydropower, History and Technology of John S Gulliver, Roger E A Arndt 138 M Manufactured Gas, History of Joel A Tarr 153 N Natural Gas, History of Christopher J Castaneda 163 Nuclear Power, History of Robert J Duffy 175 Contents O Oil Crises, Historical Perspective Mamdouh G Salameh 189 Oil Industry, History of August W Giebelhaus 203 OPEC Market Behavior, 1973-2003 A F Alhajji 215 OPEC, History of Fadhil J Chalabi 228 P Prices of Energy, History of Peter Berck, Michael J Roberts 241 Q Sociopolitical Collapse, Energy and Joseph A Tainter 251 Solar Energy, History of John Perlin 265 T Thermodynamic Sciences, History of Keith Hutchison 281 Transitions in Energy Use Arnulf Grübler 287 w War and Energy Vaclav Smil 301 Wind Energy, History of Martin Pasqualetti, Robert Righter, Paul Gipe 309 Wood Energy, History of John Perlin 323 World History and Energy Vaclav Smil 331 List of Contributors 343 Subject Index 345 vi. -

Chapter 1: Energy Challenges September 2015 1 Energy Challenges

QUADRENNIAL TECHNOLOGY REVIEW AN ASSESSMENT OF ENERGY TECHNOLOGIES AND RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES Chapter 1: Energy Challenges September 2015 1 Energy Challenges Energy is the Engine of the U.S. Economy Quadrennial Technology Review 1 1 Energy Challenges 1.1 Introduction The United States’ energy system, vast in size and increasingly complex, is the engine of the economy. The national energy enterprise has served us well, driving unprecedented economic growth and prosperity and supporting our national security. The U.S. energy system is entering a period of unprecedented change; new technologies, new requirements, and new vulnerabilities are transforming the system. The challenge is to transition to energy systems and technologies that simultaneously address the nation’s most fundamental needs—energy security, economic competitiveness, and environmental responsibility—while providing better energy services. Emerging advanced energy technologies can do much to address these challenges, but further improvements in cost and performance are important.1 Carefully targeted research, development, demonstration, and deployment (RDD&D) are essential to achieving these improvements and enabling us to meet our nation’s energy objectives. This report, the 2015 Quadrennial Technology Review (QTR 2015), examines science and technology RDD&D opportunities across the entire U.S. energy system. It focuses primarily on technologies with commercialization potential in the mid-term and beyond. It frames various tradeoffs that all energy technologies must balance, across such dimensions as diversity and security of supply, cost, environmental impacts, reliability, land use, and materials use. Finally, it provides data and analysis on RDD&D pathways to assist decision makers as they set priorities, subject to budget constraints, to develop more secure, affordable, and sustainable energy services. -

Pathways to Sustainable Energy Accelerating Energy Transition in the UNECE Region

UNEC E Pathways to Sustainable Energy Accelerating Energy Transition in the UNECE Region Energy underpins economic development and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and has a critical role to play in climate change mitigation. The recognition of the role that energy plays in modern society is highly signicant, however, there remains an important disconnection between agreed energy and climate targets and the Pathways to Sustainable Energy • Accelerating Transition in the UNECE Region approaches in place today to achieve them. Only international cooperation and innovation can deliver the accelerated and more ambitious strategies. Policies will be needed to ll the persistent gaps to achieve the 2030 Agenda. If the gaps are not addressed urgently, progressively more drastic and expensive measures will be required to avoid extreme and potentially unrecoverable social impacts as countries try to cope with climate change. This report uniquely focuses on sustainable energy in the UNECE region up to 2050 as regional economic cooperation is an important factor in achieving sustainable energy. Arriving at a state of attaining sustainable energy is a complex social, political, economic and technological challenge. The UNECE countries have not agreed on how collectively they will achieve energy for sustainable development. Given the role of the UNECE to promote economic cooperation it is important to explore the implications of dierent sustainable energy pathways and for countries to work together on developing and deploying policies and measures. Pathways to Sustainable Energy Accelerating Energy Transition in the UNECE Region 67UNECE Energy Series UNIT Palais des Nations CH - 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland E Telephone: +41(0)22 917 12 34 D E-mail: [email protected] N A Website: www.unece.org TION S UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE Pathways to Sustainable Energy - Accelerating Energy Transition in the UNECE Region ECE ENERGY SERIES No. -

Thermophotovoltaic Energy in Space Applications: Review and Future Potential A

Thermophotovoltaic energy in space applications: Review and future potential A. Datas , A. Marti ABSTRACT This article reviews the state of the art and historical development of thermophotovoltaic (TPV) energy conversion along with that of the main competing technologies, i.e. Stirling, Brayton, thermoelectrics, and thermionics, in the field of space power generation. Main advantages of TPV are the high efficiency, the absence of moving parts, and the fact that it directly generates DC power. The main drawbacks are the unproven reliability and the low rejection temperature, which makes necessary the use of relatively large radiators. This limits the usefulness of TPV to small/medium power applications (100 We-class) that includes radioisotope (RTPV) and small solar thermal (STPV) generators. In this article, next generation TPV concepts are also revisited in order to explore their potential in future space power applications. Among them, multiband TPV cells are found to be the most promising in the short term because of their higher conversion efficiencies at lower emitter temperatures; thus significantly reducing the amount of rejected heat and the required radiator mass. 1. Introduction into electricity. A few of them enable a direct conversion process (e.g. PV and fuel cells), but the majority require the intermediate generation A number of technological options exist for power generation in of heat, which is subsequently converted into electricity by a heat space, which are selected depending on the mission duration and the engine. Thus, many kinds of heat engines have been developed within electric power requirements. For very short missions, chemical energy the frame of international space power R&D programs. -

G-2: Total Primary Energy Supply

G-2: Total primary energy supply 1) General description ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1) Brief definition .................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2) Units of measurement ................................................................................................................... 2 1.3) Context………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 2) Relevance for environmental policy ......................................................................................... 2 2.1) Purpose ................................................................................................................................................ 2 2.2) Issue ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 2.3) International agreements and targets ................................................................................. 3 a) Global level ............................................................................................................................................ 3 b) Regional level ........................................................................................................................................ 3 c) Subregional level ................................................................................................................................. -

2018 Renewable Energy Data Book

2018 Renewable Energy Data Book Acknowledgments This data book was produced by Sam Koebrich, Thomas Bowen, and Austen Sharpe; edited by Mike Meshek and Gian Porro; and designed by Al Hicks and Besiki Kazaishvili of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). We greatly appreciate the input, review, and support of Jenny Heeter (NREL); Yan (Joann) Zhou (Argonne National Laboratory); and Paul Spitsen (U.S. Department of Energy). Notes Capacity data are reported in watts (typically megawatts and gigawatts) of alternating current (AC) unless indicated otherwise. The primary data represented and synthesized in the 2018 Renewable Energy Data Book come from the publicly available data sources identified on page 142. Solar photovoltaic generation data include all grid-connected utility-scale and distributed photovoltaics. Total U.S. power generation numbers in this data book may difer from those reported by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) in the Electric Power Monthly and Monthly Energy Review. Reported U.S. wind capacity and generation data do not include smaller, customer-sited wind turbines (i.e., distributed wind). Front page photo: iStock 880915412; inset photos (left to right): iStock 754519; iStock 4393369; iStock 354309; iStock 2101722; iStock 2574180; iStock 5080552; iStock 964450922, Leslie Eudy, NREL 17854; iStock 627013054 Page 2: iStock 721000; page 8: iStock 5751076; page 19: photo from Invenergy LLC, NREL 14369; page 43: iStock 750178; page 54: iStock 754519; page 63: iStock 4393369; page 71: iStock 354309; page 76: iStock 2101722; page 81: iStock 2574180; page 85: iStock 5080552; page 88: iStock 964450922; page 98: photo by Leslie Eudy, NREL 17854; page 103: iStock 955015444; page 108: iStock 11265066; page 118: iStock 330791; page 128: iStock 183287196; and page 136, iStock 501095406. -

A Global Survey of Building Energy Efficiency Policies in Cities

Urban Efficiency: A Global Survey of Building Energy Efficiency Policies in Cities Contents Foreword from C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group Foreword from Tokyo Metropolitan Government Executive Summary 1. A macro view of city-level policies 2. Objectives and methodology 3. Policy maps and global trends 3.1 Overview 3.2 Global trends illustrated by policy maps 3.2.1 Building energy codes 3.2.2 Reporting and benchmarking of energy performance data 3.2.3 Mandatory auditing and retro-commissioning 3.2.4 Emissions trading schemes 3.2.5 Green building rating and energy performance labelling 3.2.6 Financial incentives 3.2.7 Non-financial incentives 3.2.8 Awareness raising programmes 3.2.9 Promoting green leases 3.2.10 Voluntary leadership programmes 3.2.11 Government leadership 3.2.12 Other 4. Experiences from frontrunner cities 4.1 Overview 4.2 Case studies 4.2.1 Hong Kong 4.2.2 Houston 4.2.3 Melbourne 4.2.4 New York City 4.2.5 Philadelphia 4.2.6 San Francisco 4.2.7 Seattle 4.2.8 Singapore 4.2.9 Sydney 4.2.10 Tokyo 4.3 Analysis 4.3.1 Key characteristics 4.3.2 Inputs during design and implementation phase 4.3.3 Results and impacts 4.3.4 Success factors 4.3.5 Key challenges 4.3.6 Future perspectives 5. Conclusions Acknowledgements Appendices 1. List of web-based databases including information on energy efficiency policies and/or action worldwide 2. Policy map - City-led programmes 3. Questionnaire sent to cities for case studies 4. -

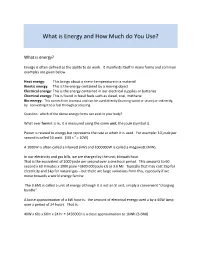

What Is Energy and How Much Do You Use?

What is Energy and How Much do You Use? What is energy? Energy is often defined as the ability to do work. It manifests itself in many forms and common examples are given below. Heat energy: This brings about a rise in temperature in a material Kinetic energy: This is the energy contained by a moving object Electrical energy: This is the energy contained in our electrical supplies or batteries Chemical energy: This is found in fossil fuels such as diesel, coal, methane Bio energy: This comes from biomass and can be used directly (burning wood or straw) or indirectly, by converting it to a fuel through processing Question: which of the above energy forms can exist in your body? What ever form it is in, it is measured using the same unit, the joule (symbol J). Power is related to energy but represents the rate at which it is used. For example: 10 joule per second is called 10 watt. (10J s-1 = 10W) A 1000W is often called a kilowatt (kW) and 1000000W is called a megawatt (MW). In our electricity and gas bills, we are charged by the unit; kilowatt hour. That is the equivalent of 1000 joule per second over a one hour period. This amounts to 60 second x 60 minutes x 1000 joule =3600 000 joule (J) or 3.6 MJ. Typically that may cost 25p for electricity and 14p for natural gas – but there are large variations from this, especially if we move towards a world energy famine. The 3.6MJ is called a unit of energy although it is not an SI unit, simply a convenient “charging bundle”. -

Chapter 4 EFFICIENCY of ENERGY CONVERSION

Chapter 4 EFFICIENCY OF ENERGY CONVERSION The National Energy Strategy reflects a National commitment to greater efficiency in every element of energy production and use. Greater energy efficiency can reduce energy costs to consumers, enhance environmental quality, maintain and enhance our standard of living, increase our freedom and energy security, and promote a strong economy. (National Energy Strategy, Executive Summary, 1991/1992) Increased energy efficiency has provided the Nation with significant economic, environmental, and security benefits over the past 20 years. To make further progress toward a sustainable energy future, Administration policy encourages investments in energy efficiency and fuel flexibility in key economic sectors. By focusing on market barriers that inhibit economic investments in efficient technologies and practices, these programs help market forces continually improve the efficiency of our homes, our transportation systems, our offices, and our factories. (Sustainable Energy Strategy, 1995) 54 CHAPTER 4 Our principal criterion for the selection of discussion topics in Chapter 3 was to provide the necessary and sufficient thermodynamics background to allow the reader to grasp the concept of energy efficiency. Here we first want to become familiar with energy conversion devices and heat transfer devices. Examples of the former include automobile engines, hair driers, furnaces and nuclear reactors. Examples of the latter include refrigerators, air conditioners and heat pumps. We then use the knowledge gained in Chapter 3 to show that there are natural (thermodynamic) limitations when energy is converted from one form to another. In Parts II and III of the book, we shall then see that additional technical limitations may exist as well.