Che Guevara Biography in Malayalam Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

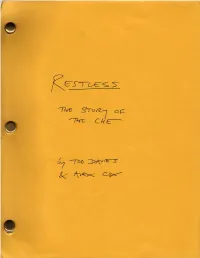

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Ernesto Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara CHEguerrilha diário da bolívia Tradução de João Pedro George l i s b o a : tinta‑da‑china MMIX © 2009, Edições tinta‑da‑china, Lda. Rua João de Freitas Branco, 35A, 1500‑627 Lisboa Tels: 21 726 90 28/9 | Fax: 21 726 90 30 E‑mail: [email protected] © 2006, Ocean Press, Centro de Estudios Che Guevara e Aleida March Fotografias © Aleida March e Centro de Estudios Che Guevara Título original: El Diario del Che en Bolivia Tradução: João Pedro George Revisão: Tinta‑da‑china Capa e composição: Vera Tavares Sobrecapa: adaptação do cartaz promocional do filme Che — Guerrilha 1.ª edição: Abril de 2009 isbn 978‑972‑8955‑94‑6 Depósito Legal n.º 290637/09 Índice Nota Introdutória 7 Diário da Bolívia 11 Comunicados Militares 273 Glossário 295 Nota Introdutória o dia 9 de Outubro de 1967, aos 39 anos de idade, Ernesto NGuevara de la Serna morreu assassinado pelo exército boli‑ viano. Fora capturado dois dias antes, e com ele uma agenda verde, onde registara os acontecimentos e as reflexões sobre a actividade diária da guerrilha, desde havia aproximadamente um ano. O diário foi confiscado pelos militares, mas logo em 1968 foi tornado público, por vias não inteiramente esclarecidas. Falta‑ vam‑lhe no entanto algumas páginas, que os serviços de informa‑ ções bolivianos tinham conseguido manter inacessíveis e que são agora editadas pela primeira vez. Evidentemente, Che foi redigindo estes textos em circuns‑ tâncias extraordinariamente adversas e é de supor que não tivesse a intenção de os publicar, pelo menos não sem antes os submeter a uma revisão. -

Díaz González, Yasmany.Pdf (7.003Mb)

UNIVERSIDAD CENTRAL “MARTA ABREU” DE LAS VILLAS FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA MECÁNICA E INDUSTRIAL DEPARTAMENTO DE INGENIERÍA MECÁNICA TRABAJO DE DIPLOMA TÍTULO: DISEÑO DEL MOLDE PARA SOPLADO DE UNA PIEZA TIPO CAPULLO Y OBTENCIÓN DEL CÓDIGO CNC DE PROGRAMACIÓN PARA LOS INSERTOS Y LA CAVIDAD IMAGEN. Autor: Yasmany Díaz González Tutores: Dr.C. Ing: RICARDO ALFONSO BLANCO Dr.C. Ing: YUDIESKI BERNAL AGUILAR Santa Clara 2017 UNIVERSIDAD CENTRAL “MARTA ABREU” DE LAS VILLAS FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA MECÁNICA DEPARTAMENTO DE INGENIERÍA MECÁNICA TRABAJAO DE DIPLOMA TÍTULO: DISEÑO DEL MOLDE PARA SOPLADO DE UNA PIEZA TIPO CAPULLO Y OBTENCIÓN DEL CÓDIGO CNC DE PROGRAMACIÓN PARA LOS INSERTOS Y LA CAVIDAD IMAGEN. Autor: YASMANY DÍAZ GONZÁLEZ. Tutores: Dr.C. Ing: RICARDO ALFONSO BLANCO. Dr.C. Ing: YUDIESKI BERNAL AGUILAR. Santa Clara 2017 Hago constar que el presente trabajo de diploma fue realizado en la Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de Las Villas como parte de la culminación de estudios de la especialidad de Ingeniería en Mecánica, autorizando a que el mismo sea utilizado por la Institución, para los fines que estime conveniente, tanto de forma parcial como total y que además no podrá ser presentado en eventos, ni publicados sin autorización de la Universidad. Firma del Autor Los abajo firmantes certificamos que el presente trabajo ha sido realizado según acuerdo de la dirección de nuestro centro y el mismo cumple con los requisitos que debe tener un trabajo de esta envergadura referido a la temática señalada. Firma del Tutor Firma del Jefe de Departamento donde se defiende el trabajo ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DISEÑO DEL MOLDE PARA SOPLADO DE UNA PIEZA TIPO CAPULLO Y OBTENCIÓN DEL CÓDIGO CNC DE PROGRAMACIÓN PARA LOS INSERTOS Y LA CAVIDAD IMAGEN. -

Hilda and Che

NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS reviews ‘A Great Feeling of Love’: Hilda and Che By Hobart Spalding sonal, which are often overlooked in The photos included in the book MY LIFE WITH CHE: THE MAKING OF writings about famous personages. help bring all this to life. A REVOLUTIONARY by Hilda Gadea Gadea, who became Che Guevara’s Life among the exile community, (Foreword by Ricardo Gadea), Palgrave wife, narrates in the first person. mostly in Guatemala but also Mex- Macmillan, 2008, 233 pp., $21.95 (hardcover) A Peruvian activist and economist, ico, constitutes another theme. The she chose exile in Guatemala after reader is struck by the deep level of the coup in her native country led solidarity that the exiles felt and their THE CUBAN REVOLUTION HAS PROBABLY by General Manuel Odria in 1948. willingness not only to protect each been given more attention in the U.S. Guatemala was then the scene of a other but to share when often they mass media than any other revolu- progressive revolution headed first had very little themselves. Clothes, tion to date. This is due to its longev- by Juan José Arevalo (1945) and af- a room, a job—all became currency ity, its proximity to the world center ter 1951 by Jacobo Arbenz. It had within the community. of empire, the United States, and not become home to many exiles fleeing Almost as in a Dostoyevsky novel, least to its many achievements. It also repressive regimes, and Hilda be- the local, national, and international reflects the colorful, dynamic person- came a fixture among that group. -

Como Ernestito, El Corajudo

Un gigante moral que crece Pág. 5 www.vanguardia.cu Santa Clara, 16 de junio de 2018 Precio: 0.20 ÓRGANO OFICIAL DEL COMITÉ PROVINCIAL DEL PARTIDO EN VILLA CLARA Como Ernestito, el corajudo Pienso en él, en el estereoti- Por Mercedes Rodríguez García Foto: SMB porque el «comandante Gueva- po que pueda formarse por la ra no hacía bandera de ser un reiteración de fotos, anécdotas, corajudo, ni le parecía impor- por las invariables efemérides tante tener el coraje convencio- celebradas casi siempre de nal. Él tenía un coraje austero, la misma forma, en el mismo el de la madre».(2) lugar, a la misma hora. Por ello, está bien expresar Por eso trato de encontrar los con fuerza, fi rmeza y justeza: rasgos primigenios. No aquellos ¡Seremos como el Che! que puedan emanar de sus an- Como el Che hombre, y como cestros, entre los que se cuentan el Che Ernestito. El niño que se —por línea materna— un virrey convertiría en leyenda. Un poco de España y buscadores de oro. genioso, pero un niño solida- Tampoco me interesan los rio, generoso, arriesgado, que del mítico rostro captado un siempre decía lo que pensaba día tremendísimo de duelo, con y nunca dejó de hacer lo que boina, melena, barba y jacket decía. ajustado al cuello, un frío y Un hombre que como padre, nublado octubre «kordasiano», a lo largo de la vida, no pudo que aún recorre el mundo en dedicar mucho tiempo a sus hi- afi ches, pancartas y carteles. jos, pues siempre dio prioridad Este mundo maltrecho, olvida- a las tareas en la dirección del do de afectos y lleno de renco- país que lo adoptó y nacionalizó res. -

Young Che.Pdf

r U E Y O U N G C H E Maxence Van der Meersch (1907-51); French author and lawyer, a humanist who wrote about the humble people of the northern region of his birth. Was awarded the Grand Prix de l'Acad6mie Frangaise in 1943 for Corps et dines [Bodies and Souls], his novel about the world of medicine, which became an international success and was translated into thirteen languages. Mario Dalmau and Dario Lopez: Cuban guerrillas who participated in the attack on the Moncada Barracks and were exiled in Mexico. Ricardo Gutierrez (1936-96): Argentine poet and doctor. He wrote The Book of Tears and The Book of Song. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939): Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist who co-founded the psychoanalytic school of psychology. He also made a long-lasting impact on many diverse fields, such as literature, film, Marxist and feminine theories, literary criticism, philosophy and psychology. Nonetheless, some of his theories remain widely disputed. Panait Istrati (1884-1935): left-wing Romanian author who wrote both in Romanian and French. He was horn in Braila and died of tuberculosis at the Filaret Sanatorium in Bucharest. Jorge Ricardo Masetti (1929-64): Argentine journalist who was the first Latin American to interview Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra. Founder and first director of the agency Prensa Latina. Close friend of Che Guevara. Led an ' insurrection in northern Argentina. Fell in comhat on 21 April 1964 in the mountains of Salta, Argentina. His noni de ^ guerre was Comandante Segundo. 338 Chronology Entries in italics signify national and international events. -

From Ascetic to Aesthetic: the Catharsis of Ernesto “Che” Guevara

From Ascetic to Aesthetic: the Catharsis of Ernesto “Che” Guevara By: William David Almeida Cuban Revolution • 26th of July Movement • Commander of the Fourth Column • Battle of Santa Clara Having originally served as the 26th of July Movement’s medical doctor, “Che” quickly rose to the ranks of commandante after demonstrating implacable fearlessness and resolve on the battlefield. Eventually, he would lead the decisive battle in Santa Clara which terminated the Batista regime. Ascetic Progression • Argentina • Cuba • Bolivia Why is it that such a privileged individual abandoned comfort time and time again to place himself into incredibly austere circumstances, and how is it that he became aestheticized (both photographically and intellectually) as a result? The Guevara Family Guatemalan Coup (1954) Tipping Point: This event concretized “Che’s” belief that armed revolution would be the only realistic catalyst to socioeconomic reform throughout Latin America. Excerpts from Che’s Message to the Tricontinetal Congress (1965) • “Latin America constitutes a more or less homogenous whole, and in almost its entire territory U.S. capital holds absolute primacy.” • “Our every action is a battle cry against imperialism and a call for unity against the great enemy of the human race: the United States of North America.” How ironic is it that the image of an individual who plotted terrorist attacks in sites such as Grand Central Station (NYC) has garnered and maintained such an intransigent following in contemporary, post-911 ‘America?’ Dichotomist -

FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America

FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America Marc Becker Subject: History of Latin America and the Oceanic World, Revolutions and Rebellions Online Publication Date: May 2019 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.218 Summary and Keywords Armed insurrections are one of three methods that the left in Latin America has tradition ally used to gain power (the other two are competing in elections, or mass uprisings often organized by labor movements as general strikes). After the triumph of the Cuban Revolu tion in 1959, guerrilla warfare became the preferred path to power given that electoral processes were highly corrupt and the general strikes too often led to massacres rather than a fundamental transformation of society. Based on the Cuban model, revolutionaries in other Latin American countries attempted to establish similar small guerrilla forces with mobile fighters who lived off the land with the support of a local population. The 1960s insurgencies came in two waves. Influenced by Che Guevara’s foco model, initial insurgencies were based in the countryside. After the defeat of Guevara’s guerrilla army in Bolivia in 1967, the focus shifted to urban guerrilla warfare. In the 1970s and 1980s, a new phase of guerrilla movements emerged in Peru and in Central America. While guer rilla-style warfare can provide a powerful response to a much larger and established mili tary force, armed insurrections are rarely successful. Multiple factors including a failure to appreciate a longer history of grassroots organizing and the weakness of the incum bent government help explain those defeats and highlight just how exceptional an event successful guerrilla uprisings are. -

CUBA Explore the World's Best-Kept Secret

adventurewomen THE DESTINATION IS JUST THE BEGINNING CUBA Explore the World's Best-Kept Secret December 9 - 18, 2021 adventurewomen 10 mount auburn street, suite 2, watertown ma 02427 t: (617) 544-9393 t: (800) 804-8606 www.adventurewomen.com adventurewomen THE DESTINATION IS JUST THE BEGINNING CUBA Explore the World's Best-Kept Secret TRIP HIGHLIGHTS ► Immerse your senses in Cuba’s thriving art, music, and cultural scene during stays in three distinct cities and towns ► Engage in insightful exchanges with women entrepreneurs and local artists ► Summon your inner salsa diva during a lesson from the pros ► Paddle a kayak through a wild pink flamingo habitat ► Enjoy charming accommodations in local paladares, and traditional meals in private, family-run restaurants ► Live the Havana lifestyle as you bicycle, stroll, cook, and cruise the city neighborhoods by classic car TRIP ROUTE adventurewomen 10 mount auburn street, suite 2, watertown ma 02427 t: (617) 544-9393 t: (800) 804-8606 www.adventurewomen.com adventurewomen THE DESTINATION IS JUST THE BEGINNING CUBA Explore the World's Best-Kept Secret QUICK VIEW ITINERARY Day 1 arrive in Havana, welcome dinner Day 2 explore Santa Clara, experience nightlife in Camagüey Day 3 explore Camagüey, pottery workshop, take in some live music Day 4 drive to Trinidad, meet a local artist to learn about her life and work Day 5 visit a coffee grower, hike in Topes de Collantes, optional evening on the town Day 6 kayak in Cienfuegos Bay, arrive in Havana Day 7 explore Old Havana, tour Havana by classic -

Young Ernesto Guevara and the Myth of Che Dan Sprinkle Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2012 Young Ernesto Guevara and the Myth of Che Dan Sprinkle Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Sprinkle, Dan, "Young Ernesto Guevara and the Myth of Che" (2012). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 256. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/256 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Young Ernesto Guevara and the Myth of Che Dan Sprinkle HST 499: Senior Seminar Spring 2012 First Reader: Dr. John Rector Second Reader: Dr. Max Geier June 6, 2012 1 Ernesto “Che” Guevara de la Serna is constantly dramatized and idolized for the things he did later in his life in the Congo, Guatemala, Cuba, and Bolivia pertaining to socialist revolution. The historical events Che partook in have been studied for decades by historians around the world and no consensus has been reached as to the morality of his actions. Many people throughout Latin America view Guevara as a heroic martyr for the people, whereas many people from the rest of the world see him as little more than a terrorist. What many of these historians fail to address is what exactly made Ernesto Guevara leave his relatively upper-middle class, loving family behind to pursue a life of revolution and guerrilla warfare. -

Book Reviews | Reseñas

European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe No. 102 (2016) October, pp. 119-153 www.erlacs.org Book Reviews | Reseñas – American Crossings: Border Politics in the Western Hemisphere, edited by Maiah Jaskoski, Arturo C. Sotomayor & Harold A. Trinkunas. Johns Hop- kins University Press, 2015. The front cover of American Crossings features a photograph by Tomas Caste- lazo of the corrugated metal wall running along the U.S.-Mexican border under a hazy blue desert sky. A thin, tall metal tower hovers along the right-hand side of the photo, a grey-steel tube camera at its pinnacle pointing outwards across the line into ostensibly Mexican territory. Adding gravitas to the tableau, an artist has attached brightly coloured coffins to the sides of the wall, each la- belled with a year and the associated number of deaths in attempts at crossing that year (2002, 371). The photograph presents an American border as a dead end space, a space of surveillance, obstruction, death. Dead end. Fortunately for the reader, and as the editors themselves are at pains to so- licit, the borders under investigation in American crossings share a ‘complexi- ty’ that belies this all-too moribund and static representation. Despite repeating the by now stale invocation that ‘in a globalized world, borders still matter’, they make a forceful argument that regional differences between the US and Latin America are key for understanding the specific socio-spatial trajectories of borders and borderlands in the area under study. Analysing borders in Latin America, they aver, shifts our attention to dynamics that depart from the ca- nonical borderland elements defining border studies in Europe or North Amer- ica.