Che's Travels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

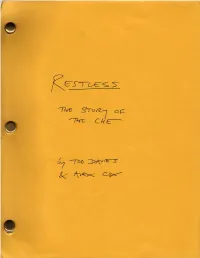

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Hilda and Che

NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS reviews ‘A Great Feeling of Love’: Hilda and Che By Hobart Spalding sonal, which are often overlooked in The photos included in the book MY LIFE WITH CHE: THE MAKING OF writings about famous personages. help bring all this to life. A REVOLUTIONARY by Hilda Gadea Gadea, who became Che Guevara’s Life among the exile community, (Foreword by Ricardo Gadea), Palgrave wife, narrates in the first person. mostly in Guatemala but also Mex- Macmillan, 2008, 233 pp., $21.95 (hardcover) A Peruvian activist and economist, ico, constitutes another theme. The she chose exile in Guatemala after reader is struck by the deep level of the coup in her native country led solidarity that the exiles felt and their THE CUBAN REVOLUTION HAS PROBABLY by General Manuel Odria in 1948. willingness not only to protect each been given more attention in the U.S. Guatemala was then the scene of a other but to share when often they mass media than any other revolu- progressive revolution headed first had very little themselves. Clothes, tion to date. This is due to its longev- by Juan José Arevalo (1945) and af- a room, a job—all became currency ity, its proximity to the world center ter 1951 by Jacobo Arbenz. It had within the community. of empire, the United States, and not become home to many exiles fleeing Almost as in a Dostoyevsky novel, least to its many achievements. It also repressive regimes, and Hilda be- the local, national, and international reflects the colorful, dynamic person- came a fixture among that group. -

Young Che.Pdf

r U E Y O U N G C H E Maxence Van der Meersch (1907-51); French author and lawyer, a humanist who wrote about the humble people of the northern region of his birth. Was awarded the Grand Prix de l'Acad6mie Frangaise in 1943 for Corps et dines [Bodies and Souls], his novel about the world of medicine, which became an international success and was translated into thirteen languages. Mario Dalmau and Dario Lopez: Cuban guerrillas who participated in the attack on the Moncada Barracks and were exiled in Mexico. Ricardo Gutierrez (1936-96): Argentine poet and doctor. He wrote The Book of Tears and The Book of Song. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939): Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist who co-founded the psychoanalytic school of psychology. He also made a long-lasting impact on many diverse fields, such as literature, film, Marxist and feminine theories, literary criticism, philosophy and psychology. Nonetheless, some of his theories remain widely disputed. Panait Istrati (1884-1935): left-wing Romanian author who wrote both in Romanian and French. He was horn in Braila and died of tuberculosis at the Filaret Sanatorium in Bucharest. Jorge Ricardo Masetti (1929-64): Argentine journalist who was the first Latin American to interview Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra. Founder and first director of the agency Prensa Latina. Close friend of Che Guevara. Led an ' insurrection in northern Argentina. Fell in comhat on 21 April 1964 in the mountains of Salta, Argentina. His noni de ^ guerre was Comandante Segundo. 338 Chronology Entries in italics signify national and international events. -

FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America

FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America Marc Becker Subject: History of Latin America and the Oceanic World, Revolutions and Rebellions Online Publication Date: May 2019 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.218 Summary and Keywords Armed insurrections are one of three methods that the left in Latin America has tradition ally used to gain power (the other two are competing in elections, or mass uprisings often organized by labor movements as general strikes). After the triumph of the Cuban Revolu tion in 1959, guerrilla warfare became the preferred path to power given that electoral processes were highly corrupt and the general strikes too often led to massacres rather than a fundamental transformation of society. Based on the Cuban model, revolutionaries in other Latin American countries attempted to establish similar small guerrilla forces with mobile fighters who lived off the land with the support of a local population. The 1960s insurgencies came in two waves. Influenced by Che Guevara’s foco model, initial insurgencies were based in the countryside. After the defeat of Guevara’s guerrilla army in Bolivia in 1967, the focus shifted to urban guerrilla warfare. In the 1970s and 1980s, a new phase of guerrilla movements emerged in Peru and in Central America. While guer rilla-style warfare can provide a powerful response to a much larger and established mili tary force, armed insurrections are rarely successful. Multiple factors including a failure to appreciate a longer history of grassroots organizing and the weakness of the incum bent government help explain those defeats and highlight just how exceptional an event successful guerrilla uprisings are. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós-Graduação Em Inglês: Estudos Linguísticos E Literários

i UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM INGLÊS: ESTUDOS LINGUÍSTICOS E LITERÁRIOS Olegario da Costa Maya Neto ACTUALIZING CHE'S HISTORY: CHE GUEVARA'S ENDURING RELEVANCE THROUGH FILM Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Inglês: Estudos Linguísticos e Literários da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Letras. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Anelise Reich Corseuil Florianópolis 2017 ii iii iv v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank my parents, Nadia and Ahyr Maya, who have always supported me and stimulated my education. Since the early years of learning how to read and write, I knew I could always rely on them. I would also like to thank my companion and best friend, Ruth Zanini. She patiently listened to me whenever I had a new insight or when I was worried. She gave me advices when I needed them and also took care of my share of the housework when I was busy. In addition, I would like to thank my brother Ahyr, who has always been a source of inspiration and advice for me. And I would like to thank my friends, especially Fabio Coura, Marcelo Barreto and Renato Muchiuti, who were vital in keeping my spirits high during the whole Master's Course. I would also like to thank all teachers and professors who for the past twenty six years have helped me learn. Unfortunately, they are too many to fit in a single page and I do not want to risk forgetting someone. Nonetheless, I would like to acknowledge their contribution. -

Guerrilla Warfare

GUERRILLA WARFARE CHE GUEVARA Introduetion to the Bison Books Edition by Mare Beeker UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS • LINCOLN ..L Guerrilla Waifare, by Che Guevara, copyright © 1961 by Monthly Review Press; reprinted by pennission of Monthly Review Press. INTRODUCTION "Guerrilla Warfare: A Method," by Che Guevara, is reprinted by pennission of the MIT Press from Che: Selected Works ofErnesto Guevara, edited and with an introduction by Rolando E. Bonachea Marc Becker and Nelson P. Valdés (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1969), copyright © 1969 by The Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Thirty years after his death, university students throughout Latin America still wear T-shirts emblazoned with Che Guevara's im Introduction © 1998 by the University of Nebraska Press age. Workers carry placards and banners featuring him as they AII rights reserved march through the streets demanding higher wages and better Manufactured in the United States of America working conditions. Zapatista guerrillas in southern Mexico paint murals depicting Che together with Emiliano Zapata and In @ The paper in this book meets the minimum requirements of dian heros. In Cuba, vendors sell Che watches to tourists. Not American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence only has he captured the popular imagination, but recently sev of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. eral authors have written lengthy biographies detailing the 1 First Bison Books printing: 1998 revolutionary's life. In the face of a political milieu that consid Most recent printing indicated by the last digit be1ow: ers socialism to be a discredited ideology, what explains this 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 continued international fascination with a guerrilla leader and romantic revolutionary who died in a failed attempt to spark a Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data hemispheric Marxist insurrection? Guevara, Ernesto, 1928-1967. -

IL CHE” …50 Anni Dalla Morte Di Che Guevara 09.10.1967 – 09.10.2017

Biblioteca cantonale Bellinzona Viale Franscini 30a 6500 Bellinzona “IL CHE” …50 anni dalla morte di Che Guevara 09.10.1967 – 09.10.2017 Bibliografia Il che … 50 anni dalla morte (Mazza Patrizia – ottobre 2017) Solo documenti presenti presso la Biblioteca cantonale di Bellinzona Che Guevara : pensiero e politica dell'utopia / Roberto Massari - Roma : Erre emme, 1994 – pp. 543 (Controcorrente ; 15) BZ-Biblioteca cantonale. Lettura. Segnatura:BCB vpve 32.13(7/8) MASS ME-Biblioteca cantonale. Magazzino (prenotazione obbligatoria, disponibile in 1 giorno). Segnatura:BCM 92 GUEV «Il Che è vivo…», hanno gridato per anni cortei e pubblicazioni di mezzo mondo. Ma per la storia del pensiero Ernesto Guevara sembrava ormai morto, visto che il compito di ricostruire le sue teorie era affidato esclusivamente a servizi giornalistici, libri ad effetto, ingenue celebrazioni apologetiche. Per quanto incredibile, era mancato fino ad oggi uno studio critico - sia in Europa che in America latina. Questo libro colma un vuoto e fornisce finalmente al pubblico la possibilità di «conoscere» il Che, dopo averne tanto «sentito parlare». Utilizzando tutto il materiale disponibile, la propria esperienza diretta a Cuba negli anni '60 e l'amicizia mantenuta per anni con la prima moglie di Guevara, l'autore traccia un ampio quadro dell'itinerario teorico del Che. Non mancheranno le sorprese, in questo itinerario, dato il carattere nettamente antidogmatico, polemico e libertario del pensiero di Guevara. Una scoperta «bella» per la storia della cultura e che ci avvicina a una comprensione di quell'«uomo nuovo», per il quale il Che lottò tutta la vita. È anche il senso della sua utopia e la tesi di questo lavoro: l'umanismo rivoluzionario di Guevara e la sua dialettica della liberazione si concludono là dove comincia il futuro (Editore) Che Guevara : utopia e rivoluzione / Jean Cormier ; [ed. -

Che Cronología

Ernesto Che Guevara. Cronología Si bien en su certificado de nacimiento constaba que Ernesto Guevara de la Serna había nacido el 14 de junio de 1928 su madre confesó treinta años mas tarde que Ernesto había nacido el 14 de mayo de 1928. 1928 14 de mayo. En la ciudad de Rosario, Argentina, nace Ernesto Guevara de la Serna, primer hijo de Ernesto Guevara Lynch y Celia de la Serna. 1929 Viven en la provincia de Misiones, donde la familia tiene un yerbatal. Nace su hermana Celia. 1930 Mayo. Ernesto sufre su primer ataque de asma. Le diagnostican afección asmática severa. 1932 La familia se radica en Bs As. Nace su hermano Roberto. 1933 Junio. Se trasladan a Alta Gracia, un pueblo en las Sierras Cordobesas, de clima propicio para los enfermos del sistema respiratorio. Vivirán alli hasta 1943. 1934 28 de enero. Nace su hermana Ana María. 1936 Estalla la guerra civil española. Su tío Córdova Ituburu es corresponsal de guerra del diario Crítica. Es la primera aproximación de Ernesto a la política. 1943 Vive en Córdoba. Concluye la escuela secundaria. Comienza una amistad con los hermanos Granado y los hermanos Ferrer. Nace su último hermano Juan Martin. CEME - Centro de Estudios Miguel Enríquez - Archivo Chile 1945 Se trasladan a Bs As. Ingresa a la facultad de medicina. Conoce a Tita Infante. Trabaja para pagarse la carrera. 1950 1 de enero. Recorre mas de 4500 km. del norte argentino con una bicicleta, a la cual le adosa un pequeño motor. Se detiene en el leprosario del Chañar. Trabaja en vialidad y en la flota mercante argentina. -

Che Guevara: You Win Or You Die by Stuart A

Children's Book and Media Review Volume 34 Issue 1 Article 20 2014 Che Guevara: You Win Or You Die by Stuart A. Kallen Lee Crowther Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Crowther, Lee (2014) "Che Guevara: You Win Or You Die by Stuart A. Kallen," Children's Book and Media Review: Vol. 34 : Iss. 1 , Article 20. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr/vol34/iss1/20 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Children's Book and Media Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Crowther: Che Guevara: You Win Or You Die by Stuart A. Kallen Author: Kallen, Stuart A. Title: Che Guevara: You Win Or You Die Year of Publication: 2012 Publisher: Twenty-First Century Books ISBN: 978-0822590354 Number of Pages: 88 Rating: Dependable Reading/Interest Level: Intermediate Keywords: Biography; Nonfiction; Argentina; Cuba; Che Guevara; Fidel Castro; Communism Stuart A. Kallen takes on the life of one of history’s more controversial figures in Che Guevara: You Win Or You Die. Ernesto “Che” Guevara, though born to a well-off family, grew up “keenly aware of the gap between rich and poor.” During his asthma-plagued youth, Che read voraciously and eclectically. In his early twenties, Guevara undertook a transcontinental journey which more deeply engrained in him a fierce indignation at the oppression of the poor. Guevara left his home country of Argentina to join Fidel Castro’s Communist revolution in Cuba, and devoted the remainder of his life to the ideals of the revolution, fighting in the Congo and later in Bolivia, where he was eventually tracked down and killed. -

Guevarism - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

مذهب جيفارا Guevarism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guevarism Guevarism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Guevarism is a theory of communist revolution and a military strategy of guerrilla warfare associated with Marxist revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara, a leading figure of the Cuban Revolution. During the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union clashed in a series of proxy wars, especially in the developing nations of the Third World, including many decolonization struggles. Contents 1 Overview 2 Criticism 3 See also 4 Notes Overview After the 1959 triumph of the Cuban insurrection led by a militant "foco" under Fidel Castro, his Argentina-born, cosmopolitan and Marxist colleague Guevara parlayed his ideology and experiences into a model for emulation (and at times, direct military intervention) around the globe. While exporting one such "focalist" revolution to Bolivia, leading an armed vanguard party there in October 1967, Guevara was captured and executed, becoming a martyr to both the World Communist Movement and the New Left. His ideology promotes exporting revolution to any country whose leader is supported by the empire (United States) and has fallen out of favor with its citizens. Guevara talks about how constant guerrilla warfare taking place in non-urban areas can overcome leaders. He introduces three points that are representative of his ideology as a whole: that the people can win with proper organization against a nation's army; that the conditions that make a revolution possible can be put in place by the popular forces; and that the popular forces always have an advantage in a non urban setting. -

Che Guevara: a False Idol for Revolutionaries

Che Guevara: A False Idol for Revolutionaries by Troy J. Sacquety 30 Veritas the mid-1960s, Ernesto “Che” Guevara de la most established families. While he squandered an In Serna, was a clear threat to American foreign inheritance, his wife, Celia, had her own and an estate policy in Latin America. His role in Cuba’s Revolution, that provided a small yearly income. Ernesto’s upbringing his outspoken criticism of the United States, and his was bohemian; as a boy he was free to do as he wished. proponency for armed Communist insurgencies in the But he was born with a serious, lingering ailment. Western Hemisphere, made him one of Washington’s top From the age of two Ernesto suffered from severe intelligence and military targets. “This asthmatic . who asthma, forcing the family to live in a dry region. His never went to military school or owned a brass button had father complained that “each day we found ourselves a greater influence on inter-American military policies more at the mercy of that damned sickness.”4 The asthma than any single man since the end of Josef Stalin.”1 Che’s made the often-bedridden Ernesto a voracious reader. He part in establishing the first Communist government in was also determined to lead an active life. Latin America was legendary in the region. In essence, Ernesto played sports and engaged in daredevil antics the U.S. Government was concerned by, not just Che to impress his friends. Although of slight build, he was the man, but what he proselytized on insurgency and especially good at rugby. -

Che Guevara: Hero Or Villain?

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State ESL for Academic Purposes Spring 3-16-2021 Che Guevara: Hero or Villain? Alberto Ramos [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/ma_tesol Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Language and Literacy Education Commons Recommended Citation Ramos, Alberto.(2020). Che Guevara: Hero or Villain?. Global Citizenship. This Learning Object is brought to you for free and open access by theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESL for Academic Purposes by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Che Guevara: Hero or Villain? Day 1 Alberto Ramos St. Cloud State University 2020 This is a unit in the course Global Citizenship for B2 CEFR EFL college students In this unit, students will be able to… • Listen for understanding • Work collaboratively in groups • Read texts critically • Understand and recall key vocabulary relating to Che and his political views • Compare and Contrast Marxism and Capitalism • Demonstrate critical thinking through public speaking • Write an organized personal response paper on Che’s revolutionary ideology Unit Plan and Activities Each day is designed for a 50 minute class period Day 1 Listening, Reading, and Speaking • 10 minutes- Introduce topic with warm up activity : general discussion questions with the whole class and an overview