ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: REFASHIONING THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

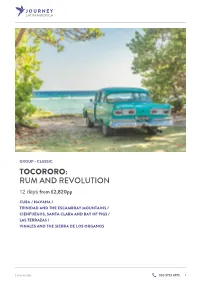

Tocororo: Rum and Revolution

12 days 5:58 24-07-2021 We are the UK’s No.1 specialist in travel to Latin As our name suggests, we are single-minded America and have been creating award-winning about Latin America. This is what sets us apart holidays to every corner of the region for over four from other travel companies – and what allows us decades; we pride ourselves on being the most to offer you not just a holiday but the opportunity to knowledgeable people there are when it comes to experience something extraordinary on inspiring travel to Central and South America and journeys throughout Mexico, Central and South passionate about it too. America. A passion for the region runs Fully bonded and licensed Our insider knowledge helps through all we do you go beyond the guidebooks ATOL-protected All our Consultants have lived or We hand-pick hotels with travelled extensively in Latin On your side when it matters character and the most America rewarding excursions Book with confidence, knowing Up-to-the-minute knowledge every penny is secure Let us show you the Latin underpinned by 40 years' America we know and love experience 5:58 24-07-2021 5:58 24-07-2021 This group tour trip begins in Havana, Cuba's inimitable capital, with its faded grandeur enlivened by the sound of salsa and rumba. From here travel on to Santa Clara, home to Che Guevara's mausoleum, and on to the cobbled streets of colonial Trinidad. You then head west to Viñales, a fertile valley punctuated with lumpy limestone mountains in the island's tobacco-growing region. -

Miércoles, 8 De Diciembre Del 2010 NACIONALES

NACIONALES miércoles, 8 de diciembre del 2010 de cuál había sido siempre nuestra conducta con (Aplausos). ¡Ahora sí que el pueblo está armado! recibido la orden de marchar sobre la gran los militares, de todo el daño que le había hecho la Yo les aseguro que si cuando éramos 12 hombres Habana y asumir el mando del campamento tiranía al Ejército y cómo no era justo que se con- solamente no perdimos la fe (Aplausos), ahora militar de Columbia (Aplausos). Se cumplirán, siderase por igual a todos los militares; que los cri- que tenemos ahí 12 tanques cómo vamos a per- sencillamente, las órdenes del presidente de minales solo eran una minoría insignificante, y que der la fe. la República y el mandato de la Revolución había muchos militares honorables en el Ejército, Quiero aclarar que en el día de hoy, esta noche, (Aplausos). que yo sé que aborrecían el crimen, el abuso y la esta madrugada, porque es casi de día, tomará De los excesos que se hayan cometido en La injusticia. posesión de la presidencia de la República, el ilus- Habana, no se nos culpe a nosotros. Nosotros no No era fácil para los militares desarrollar un tipo tre magistrado, doctor Manuel Urrutia Lleó (aplau- estábamos en Habana. De los desórdenes ocurri- determinado de acción; era lógico, que cuando los sos). ¿Cuenta o no cuenta con el apoyo del pue- dos en La Habana, cúlpese al general Cantillo y a cargos más elevados del Ejército estaban en blo el doctor Urrutia? (Aplausos y gritos). Pero los golpistas de la madrugada, que creyeron que manos de los Tabernilla, de los Pilar García, de los quiere decir, que el presidente de la República, el iban a dominar la situación allí (Aplausos). -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Pardos in Vallegrande : an exploration of the role of afromestizos in the foundation of Vallegrande, Santa Cruz, Bolivia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6m01m9bd Author Weaver Olson, Nathan Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pardos in Vallegrande: An Exploration of the Role of Afromestizos in the Foundation of Vallegrande, Santa Cruz, Bolivia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American Studies (History) by Nathan Weaver Olson Committee in Charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Chair Professor Nancy Postero Professor Eric Van Young 2010 Copyright Nathan Weaver Olson, 2010 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Nathan Weaver Olson is approved and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For Kimberly, who lived it. iv EPIGRAPH The descent beckons As the ascent beckoned. Memory is a kind of accomplishment, a sort of renewal even an initiation, since the spaces it opens are new places inhabited by hordes heretofore unrealized … William Carlos Williams v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ………………………………………………………………… iii Dedication …………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph ………………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………... vi List of Charts ………………………………………………………………….. viii List of Maps …………………………………………………………………… ix Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………. x Abstract ………………………………………………………………………… xii Introduction: Viedma and Vallegrande…………………………...……………. 1 Chapter 1: Representations of the Past ………………………………………… 10 Viedma‘s Report ………………………………………………………. 10 Vallegrande Responds …………………………………………………. 18 Pardos and Caballeros Pardos …………………………………………. 23 A Hegemonic Narrative ……………………………………………….. 33 Chapter 2: Vallegrande as Region and Frontier ………………………………. -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm). -

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Tensions Rise in Miami and Havana As Panel Issues Cuba Recommendations

Vol. 12, No. 5 May 2004 www.cubanews.com In the News Tensions rise in Miami and Havana as Senseless census? panel issues Cuba recommendations Experts wonder why results of 2002 cen- BY ANA RADELAT I restricting the amount of baggage travelers can take to Cuba, so that Havana can’t make sus are being kept secret .............Page 3 he Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba sent its long-awaited recommenda- money from fees charged for extra weight tions to President Bush on May 3, but beyond the current 40-pound limit. Religion briefs T I eliminating a provision that now allows U.S. details of the plan are shrouded in secrecy. Churches feel threatened by new sects; travelers to bring back from Cuba up to $100 Four out of the five chapters in the 500-page worth of goods, including rum and cigars. Holocaust memorial unveiled ......Page 5 report deal with proposals from an alphabet I boosting U.S. funds for programs designed soup of federal agencies on how they could help to strengthen civil society in Cuba. Bearish in Berlin a post-Castro Cuba. The fifth chapter focuses on The idea of turning off the flow of dollars to what amounts to “regime change” — specific Diplomat says German companies aren’t Castro appeals to older, largely Republican ways on hastening Fidel Castro’s downfall. Cuban-Americans who came to Florida in the rushing to invest in Cuba .............Page 6 Bush is expected to announce his support for early 1960s, but not to more recent arrivals who some of those recommendations on May 20, still have strong family ties to the island. -

Restructuring the Socialist Economy

CAPITAL AND CLASS IN CUBAN DEVELOPMENT: Restructuring the Socialist Economy Brian Green B.A. Simon Fraser University, 1994 THESISSUBMllTED IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMEW FOR THE DEGREE OF MASER OF ARTS Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies O Brian Green 1996 All rights resewed. This work my not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Siblioth&ye nationale du Canada Azcjuis;lrons and Direction des acquisitions et Bitjibgraphic Sewices Branch des services biblicxpphiques Youi hie Vofrergfereoce Our hie Ncfre rb1Prence The author has granted an L'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive ficence irrevocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant & la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationafe du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, preter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes int6ress6es. The author retains ownership of L'auteur consenre la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial th&se. Ni la thbe ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiefs de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent 6tre imprimes ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisatiow. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Sion Fraser Universi the sight to Iend my thesis, prosect or ex?ended essay (the title o7 which is shown below) to users o2 the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the Zibrary of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

De Ernesto, El “Che” Guevara: Cuatro Miradas Biográficas Y Una Novela*

Literatura y Lingüística N° 36 ISSN 0716 - 5811 / pp. 121 - 137 La(s) vida(s) de Ernesto, el “Che” Guevara: cuatro miradas biográficas y una novela* Gilda Waldman M.** Resumen La escritura biográfica, como género, alberga en su interior una gran diversidad de métodos, enfoques, miradas y modelos que comparten un rasgo central: se trata de textos interpre- tativos, pues ningún pasado individual se puede reconstruir fielmente. En este sentido, cabe referirse a algunas de las más importantes biografías existentes sobre el Che Guevara, como La vida en rojo, de Jorge G. Castañeda, (Alfaguara 1997); Che Ernesto Guevara. Una leyenda de nuestro siglo, de Pierre Kalfon (Plaza y Janés, 1997); Che Guevara. Una vida revo- lucionaria, de John Lee Anderson (Anagrama, 2006) y Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che, de Paco Ignacio Taibo II (Planeta, 1996). Por otro lado, en la vida del Che, hay silencios oscuros que las biografías no cubren, salvo de manera muy superficial. Algunos de estos vacíos son retomados por la literatura, por ejemplo, a través de la novela de Abel Posse, Los Cuadernos de Praga. Palabras clave: Che Guevara, biografías, interpretación, literatura. Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s Lives. Four Biographies and one Novel Abstract The biographical writing, as a genre, shelters inside a wide diversity of methods, approaches, points of view and models that share a central trait: it is an interpretative text, since no individual past can be faithfully reconstructed. In this sense, it is worth referring to some of the most diverse and important biographies written about Che Guervara, (Jorge G. Castañeda: La vida en rojo, Alfaguara 1997; Pierre Kalfon: Che Ernesto Guevara. -

Press Release Author A.C. Frieden Follows Che Guevara's Trail in Bolivia

Press Release Author A.C. Frieden Follows Che Guevara’s Trail in Bolivia VALLEGRANDE, Bolivia (Nov. 22, 2007) -- Author A.C. Frieden traveled to Bolivia to research Che Guevara’s 1960s revolutionary movement in order to complete his upcoming novel Where Spies Go To Die. Arriving in Santa Cruz, Bolivia’s largest city and one of the transit points for Che Guevara and his rebels in 1966, Frieden visited many of the city’s key sites and interviewed a number of locals in preparation for his journey south. Above: Monument dedicated to Che Guevara located in the center of the tiny village of La Higuera, in south-central Bolivia, where the guerrilla leader was executed in 1967. After visiting Samaipata, he went on to Vallegrande to see various sites related to Che Guevara. In particular, Frieden visited the Señor de Malta hospital, where Che’s body was flown to after his execution in La Higuera. Frieden toured the airfield and nearby grounds where Che’s remains and those of his most loyal comrades were secretly buried in 1967. For several days Frieden ventured south from Vallegrande across rugged mountain roads to visit remote villages and trails connected to Che Guevara’s doomed rebellion. After visiting the town of Pucara, Frieden arrived in La Higuera and toured the schoolhouse where Che was executed by CIA-backed Bolivian troops shortly after his capture in the nearby canyon called Quebrada de Yuro. In La Higuera, Frieden interviewed a village elder who had witnessed Che’s arrival into the village 40 years earlier. Frieden returned to Samaipata, where he toured El Fuerte, an archeological site (designated a world heritage site by UNESCO) that was inhabited by three populations over several centuries: the Amazonian, Inca and Colonial civilizations. -

Hilda and Che

NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS reviews ‘A Great Feeling of Love’: Hilda and Che By Hobart Spalding sonal, which are often overlooked in The photos included in the book MY LIFE WITH CHE: THE MAKING OF writings about famous personages. help bring all this to life. A REVOLUTIONARY by Hilda Gadea Gadea, who became Che Guevara’s Life among the exile community, (Foreword by Ricardo Gadea), Palgrave wife, narrates in the first person. mostly in Guatemala but also Mex- Macmillan, 2008, 233 pp., $21.95 (hardcover) A Peruvian activist and economist, ico, constitutes another theme. The she chose exile in Guatemala after reader is struck by the deep level of the coup in her native country led solidarity that the exiles felt and their THE CUBAN REVOLUTION HAS PROBABLY by General Manuel Odria in 1948. willingness not only to protect each been given more attention in the U.S. Guatemala was then the scene of a other but to share when often they mass media than any other revolu- progressive revolution headed first had very little themselves. Clothes, tion to date. This is due to its longev- by Juan José Arevalo (1945) and af- a room, a job—all became currency ity, its proximity to the world center ter 1951 by Jacobo Arbenz. It had within the community. of empire, the United States, and not become home to many exiles fleeing Almost as in a Dostoyevsky novel, least to its many achievements. It also repressive regimes, and Hilda be- the local, national, and international reflects the colorful, dynamic person- came a fixture among that group. -

Download The

Las formas del duelo: memoria, utopía y visiones apocalípticas en las narrativas de la guerrilla mexicana (1979-2008) by José Feliciano Lara Aguilar B.J., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Hispanic Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2016 © José Feliciano Lara Aguilar, 2016 Abstract This study analyzes six literary works of the Mexican contemporary guerrilla that covers the years 1979 to 2008: Al cielo por asalto (1979) by Agustín Ramos, ¿Por qué no dijiste todo? (1980) and La patria celestial (1992) by Salvador Castañeda, Morir de sed junto a la fuente. Sierra de Chihuahua 1968 (2001) by Minerva Armendáriz Ponce, Veinte de cobre (2004) by Fritz Glockner, and Vencer o morir (2008) by Leopoldo Ayala. In both their form and structure, these narratives address the notion of mourning, as well as its inherent categories, such as: work of mourning or grief work, melancholy, loss, grief, remnants, and specters, among others, which call into question and destabilize the generalized social discourse. In this tension, I observe the emergence of aesthetic languages that take place within the post-revolutionary imaginary of the 1960’s, and 1970’s with the exhaustion of revolutionary imaginary that was predominant in the preceding decades. These aesthetic languages provide mourning with new contents, organized in three fields: memory, utopia, and apocalyptic visions, which recreate mourning as a symbolic space where an important social struggle for the reconstruction of the past is still ongoing.