Visual Culture and Us-Cuban Relations, 1945-2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1 PETER C. BJARKMAN www.bjarkman.com Cuban Baseball Historian Author and Internet Journalist Post Office Box 2199 West Lafayette, IN 47996-2199 USA IPhone Cellular 1.765.491.8351 Email [email protected] Business phone 1.765.449.4221 Appeared in “No Reservations Cuba” (Travel Channel, first aired July 11, 2011) with celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain Featured in WALL STREET JOURNAL (11-09-2010) front page story “This Yanqui is Welcome in Cuba’s Locker Room” PERSONAL/BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Born: May 19, 1941 (72 years old), Hartford, Connecticut USA Terminal Degree: Ph.D. (University of Florida, 1976, Linguistics) Graduate Degrees: M.A. (Trinity College, 1972, English); M.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1970, Education) Undergraduate Degree: B.S.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1963, Education) Languages: English and Spanish (Bilingual), some basic Italian, study of Japanese Extensive International Travel: Cuba (more than 40 visits), Croatia /Yugoslavia (20-plus visits), Netherlands, Italy, Panama, Spain, Austria, Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala, Canada, Japan. Married: Ronnie B. Wilbur, Professor of Linguistics, Purdue University (1985) BIBLIOGRAPHY March 2014 MAJOR WRITING AWARDS 2008 Winner – SABR Latino Committee Eduardo Valero Memorial Award (for “Best Article of 2008” in La Prensa, newsletter of the SABR Latino Baseball Research Committee) 2007 Recipient – Robert Peterson Recognition Award by SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, for advancing public awareness -

Cuba and the World.Book

CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Edited by M. Font Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies Presented at the international symposium “Cuba Futures: Past and Present,” organized by the The Cuba Project Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies The Graduate Center/CUNY, March 31–April 2, 2011 CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies www.cubasymposium.org www.bildner.org Table of Contents Preface v Cuba: Definiendo estrategias de política exterior en un mundo cambiante (2001- 2011) Carlos Alzugaray Treto 1 Opening the Door to Cuba by Reinventing Guantánamo: Creating a Cuba-US Bio- fuel Production Capability in Guantánamo J.R. Paron and Maria Aristigueta 47 Habana-Miami: puentes sobre aguas turbulentas Alfredo Prieto 93 From Dreaming in Havana to Gambling in Las Vegas: The Evolution of Cuban Diasporic Culture Eliana Rivero 123 Remembering the Cuban Revolution: North Americans in Cuba in the 1960s David Strug 161 Cuba's Export of Revolution: Guerilla Uprisings and Their Detractors Jonathan C. Brown 177 Preface The dynamics of contemporary Cuba—the politics, culture, economy, and the people—were the focus of the three-day international symposium, Cuba Futures: Past and Present (organized by the Bildner Center at The Graduate Center, CUNY). As one of the largest and most dynamic conferences on Cuba to date, the Cuba Futures symposium drew the attention of specialists from all parts of the world. Nearly 600 individuals attended the 57 panels and plenary sessions over the course of three days. Over 240 panelists from the US, Cuba, Britain, Spain, Germany, France, Canada, and other countries combined perspectives from various fields including social sciences, economics, arts and humanities. -

The Global Visual Memory a Study of the Recognition and Interpretation of Iconic and Historical Photographs

The Global Visual Memory A Study of the Recognition and Interpretation of Iconic and Historical Photographs Het Mondiaal Visueel Geheugen Een studie naar de herkenning en interpretatie van iconische en historische foto’s (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 19 juni 2019 des middags te 2.30 uur door Rutger van der Hoeven geboren op 4 juni 1974 te Amsterdam Promotor: Prof. dr. J. Van Eijnatten Table of Contents Abstract 2 Preface 3 Introduction 5 Objectives 8 Visual History 9 Collective Memory 13 Photographs as vehicles of cultural memory 18 Dissertation structure 19 Chapter 1. History, Memory and Photography 21 1.1 Starting Points: Problems in Academic Literature on History, Memory and Photography 21 1.2 The Memory Function of Historical Photographs 28 1.3 Iconic Photographs 35 Chapter 2. The Global Visual Memory: An International Survey 50 2.1 Research Objectives 50 2.2 Selection 53 2.3 Survey Questions 57 2.4 The Photographs 59 Chapter 3. The Global Visual Memory Survey: A Quantitative Analysis 101 3.1 The Dataset 101 3.2 The Global Visual Memory: A Proven Reality 105 3.3 The Recognition of Iconic and Historical Photographs: General Conclusions 110 3.4 Conclusions About Age, Nationality, and Other Demographic Factors 119 3.5 Emotional Impact of Iconic and Historical Photographs 131 3.6 Rating the Importance of Iconic and Historical Photographs 140 3.7 Combined statistics 145 Chapter 4. -

AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 Ajdoc50 2019

Declassified AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 ajdoc50 2019 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Abolition of the death penalty in Council of Europe member and observer states,1 Belarus and countries whose parliaments have co-operation status2 – situation report Revised information note General rapporteur: Mr Titus CORLĂŢEAN, Romania, Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group 1. Introduction 1. Having been appointed general rapporteur on the abolition of the death penalty at the Committee meeting of 13 December 2018, I have had the honour to continue the outstanding work done by Mr Yves Cruchten (Luxemburg, SOC), Ms Meritxell Mateu Pi (Andorra, ALDE), Ms Marietta Karamanli (France, SOC), Ms Marina Schuster (Germany, ALDE), and, before her, Ms Renate Wohlwend (Liechtenstein, EPP/CD).3 2. This document updates the previous information note with regard to the development of the situation since October 2018, which was considered at the Committee meeting in Strasbourg on 10 October 2018. 3. This note will first of all provide a brief overview of the international and European legal framework, and then highlight the current situation in states that have abolished the death penalty only for ordinary crimes, those that provide for the death penalty in their legislation but do not implement it and those that actually do apply it. It refers solely to Council of Europe member states (the Russian Federation), observer states (United States, Japan and Israel), states whose parliaments hold “partner for democracy” status, Kazakhstan4 and Belarus, a country which would like to have closer links with the Council of Europe. Since March 2012, the Parliamentary Assembly’s general rapporteurs have issued public statements relating to executions and death sentences in these states or have proposed that the Committee adopt statements condemning capital punishment as inhuman and degrading. -

VADP 2015 Annual Report Accomplishments in 2015

2015 Annual Report Working to End the Death Penalty through Education, Organizing and Advocacy for 24 years VADP Executive Directors, Past and Present From left: Beth Panilaitis (2008 -2010), Steve Northup (2011 -2014), Jack Payden -Travers (2002 -2007), and Michael Stone (2015). Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty P.O. Box 12222 Richmond, VA 23241 (434) 960 -7779 [email protected] www.vadp.org Message from the VADP Board President Dear VADP Supporter, resources to band together the various groups and Last year was a time of strong forward movement individuals who oppose the death penalty, for VADP. In January, we hired Michael Stone, whatever their reasons, into a cohesive force. our first full time executive director in four years, I would like to thank those of you who made a and that led to the implementation of bold new monetary donation to VADP in 2015. But our strategies and expanded programs. work is not done. So I ask you to increase your In 2015 we learned what can be accomplished in support in 2016 and to help us find others to join today’s politics when groups with different overall this important movement. And, if you are not yet purposes decide to work together on a specific a supporter of VADP, now is the time to join our shared objective — such as vital work to end the death penalty in Virginia, death penalty abolition. That, once and for all. happily, is starting to occur. Sincerely, As an example, nationally and Kent Willis in Virginia activists from every Board President point on the political spectrum are joining an extraordinary new movement to re -examine The Death Penalty in Virginia how we waste tax dollars on our expensive and ineffective criminal justice system, including ♦ Virginia has executed 111 men and women capital punishment. -

COUNCIL FILE NO. Fd-0 5 / Cj

COUNCIL FILE NO. COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 ,fd- 0 5 / I cj- APPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCIL The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1075-81) without being referred to the Public Works Comm ittee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: _} A. Future Street Acceptance. _} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). _} C. Dedication of Easement(s). _} D. Release of Restriction(s) . ...KJ E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. _} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. _} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. _} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAL/DISAPPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* Council Office of the District Public Works Committee Chairperson *DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date ____ notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date ____ scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: _ ___} Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. ____} Other: PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCIL FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council Ofthe City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C. -

Itinéraires, 2019-2 Et 3 | 2019 Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: the Case of Nicaragua 2

Itinéraires Littérature, textes, cultures 2019-2 et 3 | 2019 Corps masculins et nation : textes, images, représentations Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: The Case of Nicaragua Performances de genre en contextes révolutionnaires : le cas du Nicaragua Viria Delgadillo Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/itineraires/6929 DOI: 10.4000/itineraires.6929 ISSN: 2427-920X Publisher Pléiade Electronic reference Viria Delgadillo, « Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: The Case of Nicaragua », Itinéraires [Online], 2019-2 et 3 | 2019, Online since 13 December 2019, connection on 15 December 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/itineraires/6929 ; DOI : 10.4000/itineraires.6929 This text was automatically generated on 15 December 2019. Itinéraires est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: The Case of Nicaragua 1 Performances of Gender in Revolutionary Contexts: The Case of Nicaragua Performances de genre en contextes révolutionnaires : le cas du Nicaragua Viria Delgadillo Introduction 1 Gender policies were at the heart of the 1980s Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional’s (FSLN) plans for social change. These policies were crucial to the legitimation of the Sandinista government, both domestically and abroad. In the existing literature on the Nicaraguan revolution, the issues of gender and legal reform as well as gender and revolutionary ideology have been dealt with at length. Molyneux’s (2001), Kampwirth’s (1998, 2006, 2013, 2015) and Montoya’s (2003) illuminating works on Sandinista law-making and gender ideology address how revolutionary ideology shapes legislation regarding women, LGBTQI individuals and the family. -

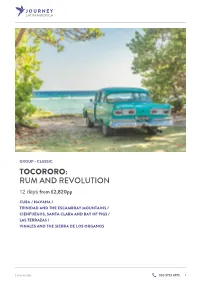

Tocororo: Rum and Revolution

12 days 5:58 24-07-2021 We are the UK’s No.1 specialist in travel to Latin As our name suggests, we are single-minded America and have been creating award-winning about Latin America. This is what sets us apart holidays to every corner of the region for over four from other travel companies – and what allows us decades; we pride ourselves on being the most to offer you not just a holiday but the opportunity to knowledgeable people there are when it comes to experience something extraordinary on inspiring travel to Central and South America and journeys throughout Mexico, Central and South passionate about it too. America. A passion for the region runs Fully bonded and licensed Our insider knowledge helps through all we do you go beyond the guidebooks ATOL-protected All our Consultants have lived or We hand-pick hotels with travelled extensively in Latin On your side when it matters character and the most America rewarding excursions Book with confidence, knowing Up-to-the-minute knowledge every penny is secure Let us show you the Latin underpinned by 40 years' America we know and love experience 5:58 24-07-2021 5:58 24-07-2021 This group tour trip begins in Havana, Cuba's inimitable capital, with its faded grandeur enlivened by the sound of salsa and rumba. From here travel on to Santa Clara, home to Che Guevara's mausoleum, and on to the cobbled streets of colonial Trinidad. You then head west to Viñales, a fertile valley punctuated with lumpy limestone mountains in the island's tobacco-growing region. -

Miércoles, 8 De Diciembre Del 2010 NACIONALES

NACIONALES miércoles, 8 de diciembre del 2010 de cuál había sido siempre nuestra conducta con (Aplausos). ¡Ahora sí que el pueblo está armado! recibido la orden de marchar sobre la gran los militares, de todo el daño que le había hecho la Yo les aseguro que si cuando éramos 12 hombres Habana y asumir el mando del campamento tiranía al Ejército y cómo no era justo que se con- solamente no perdimos la fe (Aplausos), ahora militar de Columbia (Aplausos). Se cumplirán, siderase por igual a todos los militares; que los cri- que tenemos ahí 12 tanques cómo vamos a per- sencillamente, las órdenes del presidente de minales solo eran una minoría insignificante, y que der la fe. la República y el mandato de la Revolución había muchos militares honorables en el Ejército, Quiero aclarar que en el día de hoy, esta noche, (Aplausos). que yo sé que aborrecían el crimen, el abuso y la esta madrugada, porque es casi de día, tomará De los excesos que se hayan cometido en La injusticia. posesión de la presidencia de la República, el ilus- Habana, no se nos culpe a nosotros. Nosotros no No era fácil para los militares desarrollar un tipo tre magistrado, doctor Manuel Urrutia Lleó (aplau- estábamos en Habana. De los desórdenes ocurri- determinado de acción; era lógico, que cuando los sos). ¿Cuenta o no cuenta con el apoyo del pue- dos en La Habana, cúlpese al general Cantillo y a cargos más elevados del Ejército estaban en blo el doctor Urrutia? (Aplausos y gritos). Pero los golpistas de la madrugada, que creyeron que manos de los Tabernilla, de los Pilar García, de los quiere decir, que el presidente de la República, el iban a dominar la situación allí (Aplausos). -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm). -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

Linda Lucero Collection on La Raza Silkscreen Center/La Raza Graphics 1971-1990 CEMA 40

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt396nc691 No online items Guide to the Linda Lucero collection on La Raza Silkscreen Center/La Raza Graphics 1971-1990 CEMA 40 Finding aid prepared by Alexander Hauschild, 2006 UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Email: [email protected]; URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2006 CEMA 40 1 Title: Linda Lucero collection on La Raza Silkscreen Center/La Raza Graphics Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 40 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 5.0 linear feet(103 silkscreen prints and 558 slides) Date (inclusive): 1971-1990 Abstract: Linda Lucero collection on La Raza Silkscreen Center/La Raza Graphics [1971-1990]. As early as 1970, La Raza Silkscreen/La Raza Graphics Center was producing silkscreen prints by Chicano and Latino artists. The organizers and artists of what was originally called La Raza Silkscreen Center designed and printed posters in a makeshift studio in the back of La Raza Information Center (CEMA 40). Physical location: Del Norte creator: Lucero, Linda Access restrictions The collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained.