Cuba and the World.Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 Ajdoc50 2019

Declassified AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 ajdoc50 2019 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Abolition of the death penalty in Council of Europe member and observer states,1 Belarus and countries whose parliaments have co-operation status2 – situation report Revised information note General rapporteur: Mr Titus CORLĂŢEAN, Romania, Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group 1. Introduction 1. Having been appointed general rapporteur on the abolition of the death penalty at the Committee meeting of 13 December 2018, I have had the honour to continue the outstanding work done by Mr Yves Cruchten (Luxemburg, SOC), Ms Meritxell Mateu Pi (Andorra, ALDE), Ms Marietta Karamanli (France, SOC), Ms Marina Schuster (Germany, ALDE), and, before her, Ms Renate Wohlwend (Liechtenstein, EPP/CD).3 2. This document updates the previous information note with regard to the development of the situation since October 2018, which was considered at the Committee meeting in Strasbourg on 10 October 2018. 3. This note will first of all provide a brief overview of the international and European legal framework, and then highlight the current situation in states that have abolished the death penalty only for ordinary crimes, those that provide for the death penalty in their legislation but do not implement it and those that actually do apply it. It refers solely to Council of Europe member states (the Russian Federation), observer states (United States, Japan and Israel), states whose parliaments hold “partner for democracy” status, Kazakhstan4 and Belarus, a country which would like to have closer links with the Council of Europe. Since March 2012, the Parliamentary Assembly’s general rapporteurs have issued public statements relating to executions and death sentences in these states or have proposed that the Committee adopt statements condemning capital punishment as inhuman and degrading. -

VADP 2015 Annual Report Accomplishments in 2015

2015 Annual Report Working to End the Death Penalty through Education, Organizing and Advocacy for 24 years VADP Executive Directors, Past and Present From left: Beth Panilaitis (2008 -2010), Steve Northup (2011 -2014), Jack Payden -Travers (2002 -2007), and Michael Stone (2015). Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty P.O. Box 12222 Richmond, VA 23241 (434) 960 -7779 [email protected] www.vadp.org Message from the VADP Board President Dear VADP Supporter, resources to band together the various groups and Last year was a time of strong forward movement individuals who oppose the death penalty, for VADP. In January, we hired Michael Stone, whatever their reasons, into a cohesive force. our first full time executive director in four years, I would like to thank those of you who made a and that led to the implementation of bold new monetary donation to VADP in 2015. But our strategies and expanded programs. work is not done. So I ask you to increase your In 2015 we learned what can be accomplished in support in 2016 and to help us find others to join today’s politics when groups with different overall this important movement. And, if you are not yet purposes decide to work together on a specific a supporter of VADP, now is the time to join our shared objective — such as vital work to end the death penalty in Virginia, death penalty abolition. That, once and for all. happily, is starting to occur. Sincerely, As an example, nationally and Kent Willis in Virginia activists from every Board President point on the political spectrum are joining an extraordinary new movement to re -examine The Death Penalty in Virginia how we waste tax dollars on our expensive and ineffective criminal justice system, including ♦ Virginia has executed 111 men and women capital punishment. -

Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission

The Report of the The Report Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission Review Penalty Oklahoma Death The Report of the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission OKDeathPenaltyReview.org The Report of the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission The Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission is an initiative of The Constitution Project®, which sponsors independent, bipartisan committees to address a variety of important constitutional issues and to produce consensus reports and recommendations. The views and conclusions expressed in these reports, statements, and other material do not necessarily reflect the views of members of its Board of Directors or its staff. For information about this report, or any other work of The Constitution Project, please visit our website at www. constitutionproject.org or e-mail us at [email protected]. Copyright © March 2017 by The Constitution Project ®. All rights reserved. No part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of The Constitution Project. Book design by Keane Design & Communications, Inc/keanedesign.com. Table of Contents Letter from the Co-Chairs .........................................................................................................................................i The Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission ..............................................................................iii Executive Summary................................................................................................................................................. -

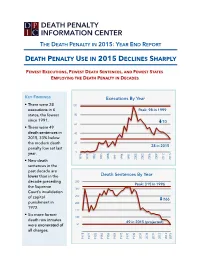

Year End Report

THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT DEATH PENALTY USE IN 2015 DECLINES SHARPLY FEWEST EXECUTIONS, FEWEST DEATH SENTENCES, AND FEWEST STATES EMPLOYING THE DEATH PENALTY IN DECADES KEY FINDINGS Executions By Year • There were 28 100 executions in 6 Peak: 98 in 1999 states, the fewest 80 since 1991. ⬇70 60 • There were 49 death sentences in 40 2015, 33% below the modern death 20 28 in 2015 penalty low set last year. 0 • New death 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 sentences in the past decade are lower than in the Death Sentences By Year decade preceding 350 Peak: 315 in 1996 the Supreme 300 Court’s invalidation of capital 250 ⬇266 punishment in 200 1972. 150 • Six more former 100 death row inmates 49 in 2015 (projected) were exonerated of 50 all charges. 1974 1977 1980 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2015 THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT U.S. DEATH PENALTY DECLINE ACCELERATES IN 2015 By all measures, use of and support for the death penalty Executions by continued its steady decline in the United States in 2015. The 2015 2014 State number of new death sentences imposed in the U.S. fell sharply from already historic lows, executions dropped to Texas 13 10 their lowest levels in 24 years, and public opinion polls revealed that a majority of Americans preferred life without Missouri 6 10 parole to the death penalty. Opposition to capital punishment polled higher than any time since 1972. -

Editor's Note

www.cubanews.com ISSN 1073-7715 Volume 6 Number 10 THE MIAMI HERALD PUBLISHING COMPANY October 1998 Editor's Note MAJOR DEVELOPMENTS Hurricane Georges Impact Food Supply Shrinks There has always been an Alice in Wonderland quality to developments in Already reeling from a drought, Cuba got Meanwhile, the combined effect of natural Cuba, but a series of recent develop- hit by another catastrophe in the form of disasters, market fluctuations and such ments seems particularly bizarre and Hurricane Georges. The disaster didn’t stop could have a devastating impact on the rich in irony. Fidel Castro from suggesting that Cuba’s already eroded living standards of Cubans. Take, for example, Fidel Castro’s com- economy could serve as a model to the More food will have to be imported. ments on the world economy. At the world. See Agriculture/The Economy, page 9 moment, Cuba is reeling from the impact See The Economy, Pages 6 & 7 of natural and man-made disasters that Aid Package in Jeopardy raise questions about whether Cuba’s Condos in Cuba Despite the dire situation, President economy will experience any growth A Canadian company is joining Gran Castro grandly rebuffed U.S. participation in whatsoever this year. But that has not Caribe to build Cuba’s first condos and time- an emergency food relief plan that the UN is stopped him from pointing with glee at share facilities. The development will be trying to put together. This has put the the plunge in stock market prices. located on some prime beachfront property. entire package in jeopardy. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Cuba in the Time of Coronavirus: Exploiting a Global Crisis

Cuba in the time of coronavirus: exploiting a global crisis Part I: Pandemic as opportunity April 7, 2020 If any country was ready for the global pandemic, it was Cuba … but not how one would expect. Its regime has responded to the coronavirus crisis by kicking into high gear to reap economic and political gain while attempting to enhance its international image, blame the United States for its problems, and erode its economic sanctions. This time, however, its usual trade-off of repressing its people for external gain is looking like a riskier gamble. Photo: CubaDebate.com In early to mid-March 2020, as most countries took increasingly drastic measures to contain the spread of coronavirus, the Cuban government was striking deals to hire out its indentured doctors, hype its questionable medications, and lure tourists while ignoring the cost to its own population. Its huge state apparatus instantly deployed its arsenal of asymmetrical weapons ¾intelligence and propaganda¾ that are the hallmark of its unique brand of soft power.1 It has proven quite effective to “alter the behavior of others to get what it wants”2 in the world stage and it has an uncanny ability to use its people as political and economic weapons. Although the 61-year old Communist regime rules over a repressed and impoverished people and a tiny, bankrupt economy, it has carefully crafted a fake narrative of Cuba as a “medical powerhouse” and “the world’s 1 Joseph Nye, a political scientist and former Clinton administration official, coined the post-Cold War concept of “soft power in a 1990 Foreign Policy piece. -

'The Cuban Question' and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964

‘The Cuban question’ and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964 LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101153/ Version: Published Version Article: Harmer, Tanya (2019) ‘The Cuban question’ and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964. Journal of Cold War Studies, 21 (3). pp. 114-151. ISSN 1520-3972 https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00896 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ The “Cuban Question” and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959–1964 ✣ Tanya Harmer In January 1962, Latin American foreign ministers and U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk arrived at the Uruguayan beach resort of Punta del Este to debate Cuba’s position in the Western Hemisphere. Unsurprisingly for a group of representatives from 21 states with varying political, socioeconomic, and geo- graphic contexts, they had divergent goals. Yet, with the exception of Cuba’s delegation, they all agreed on why they were there: Havana’s alignment with “extra-continental communist powers,” along with Fidel Castro’s announce- ment on 1 December 1961 that he was a lifelong Marxist-Leninist, had made Cuba’s government “incompatible with the principles and objectives of the inter-American system.” A Communist offensive in Latin America of “in- creased intensity” also meant “continental unity and the democratic institu- tions of the hemisphere” were “in danger.”1 After agreeing on these points, the assembled officials had to decide what to do about Cuba. -

Cuba: Beyond the Crossroads

Ron Ridenour CUBA: BEYOND THE CROSSROADS Socialist Resistance, London Socialist Resistance would be glad to have readers’ opinions of this book, its design and translations, and any suggestions you may have for future publications or wider distribution. Socialist Resistance books are available at special quantity discounts to educational and non-profit organizations, and to bookstores. To contact us, please write to: Socialist Resistance, PO Box 1109, London, N4 2UU, Britain or email us at: [email protected] or visit our website at: www.socialistresistance.net iv Set in 11pt Joanna Designed by Ed Fredenburgh Published by Socialist Resistance (second edition, revised April 2007) Printed in Britain by Lightning Source ISBN 0-902869-95-0 EAN 9 780902 869950 © Ron Ridenour, 2007 Readers are encouraged to visit www.ronridenour.com To contact the author, please email [email protected] Contents Introduction vii Preface viii 1 Return to Cuba 1 2 Comparing Living Standards 5 3 Tenacious Survival 12 4 The Blockade Squeeze 17 5 Enemies of the State 21 6 The Battle for Food 26 7 Life on the Farm 31 8 Feeding a Nation 35 9 From Farm to Table 39 v 10 On the Market 44 11 A Farewell to Farms 48 12 Health for All 51 13 Education for All 55 14 Exporting Human Capital 60 15 Media Openings 65 16 Cultural Rectification 69 17 Revolutionary Morality 73 18 The Big Challenge; forging communist consciousness 78 19 Fidel Leadership 82 20 Me and Fidel 89 21 Leadership after Fidel 93 22 Beyond the Crossroads 102 CUBA: TENAZ PALMA REAL 108 CUBA: TENACIOUS ROYAL PALM 109 Acknowledgements I wish to thank “Morning Star” features editor Richard Bagley for his excellent editing of my 2006 series on Cuba today. -

It's Getting Dark for Shortwave in Atlanta! – 8Pm

It's getting dark for shortwave in Atlanta! – 8pm The gray line, also known as the terminator (I'll be baaack) is practically here. Do you know we can use the gray line to communicate (or hear other stations) much easier than normal? When it's dusk here in Atlanta (in August), you can make contact with stations in Southern Greenland, Northern Scandinavia, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Western India quite easily. Load any gray line program on your computer to see for yourself. By the way, if you're an aspiring SWL or ham DX'er, you'll use the gray line often. Sometimes twice a day! Don't forget the dawn terminator, which highlights different parts of the world. North American pirate radio is definitely starting now. Especially on weekends and holidays. 6925 USB is still the most active frequency. Last week, I heard 3 different pirates at the same time! 6925, 6930 & 6935. Amazing. Signals are much stronger than any other time of the day. Many stations are beaming towards North America now. Many of them are religious, which I will avoid in this article. Some stations are quite interesting. Others extremely boring - usually government run. Some stations seem very strong for being so far away (Radio China International and Voice of Vietnam come to mind). That's because they lease transmitters from Canada to get much stronger signals into North America. Something to be said for one-hop propagation. China Radio International is even broadcasting to us in digital DRM delivering great sounding audio. So what are some of the better stations we can hear on short wave after eating dinner Tim? You can try Radio New Zealand. -

Latin America Spanish Only

Newswire.com LLC 5 Penn Plaza, 23rd Floor| New York, NY 10001 Telephone: 1 (800) 713-7278 | www.newswire.com Latin America Spanish Only Distribution to online destinations, including media and industry websites and databases, through proprietary and news agency networks (DyN and Notimex). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: • Posting to online services and portals. • Coverage on Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service, Newswire for Journalists, reaching 100,000 registered journalists from more than 170 countries and in more than 40 different languages. • Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Comprehensive newswire distribution to news media in 19 Central and South American countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Domincan Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela. Translated and distributed in Spanish. Please note that this list is intended for general information purposes and may adjust from time to time without notice. 4,028 Points Country Media Point Media Type Argentina 0223.com.ar Online Argentina Acopiadores de Córdoba Online Argentina Agensur.info (Agencia de Noticias del Mercosur) Agencies Argentina AgriTotal.com Online Argentina Alfil Newspaper Argentina Amdia blog Blog Argentina ANRed (Agencia de Noticias Redacción) Agencies Argentina Argentina Ambiental -

Official Journal C 187 Volume 37 of the European Communities 9 July 1994

ISSN 0378-6986 Official Journal C 187 Volume 37 of the European Communities 9 July 1994 English edition Information and Notices Notice No Contents Page I Information Council and Commission 94/C 187/01 Missions of third countries : Accreditations 1 Commission 94/C 187/02 Ecu 3 94/C 187/03 Communication of Decisions under sundry tendering procedures in agriculture (cereals) 4 94/C 187/04 The improvement of the fiscal environment of small and medium-sized enter prises (') 5 94/C 187/05 Notice pursuant to Article 19 (3) of Council Regulation No 17 concerning case No IV/34.331 — BFGoodrich/Messier-Bugatti (') 11 94/C 187/06 Notice of initiation of a review of Regulation (EEC) No 1798 /90 as amended by Regulations (EEC) No 2966/92 and (EEC) No 2455/93 imposing anti-dumping duties relating to imports of monosodium glutamate originating in Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand and of the corresponding Commission Decisions accepting undertakings in that connection 13 94/C 187/07 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case No IV/M.458 — Electrolux/ AEG) 0) 14 94/C 187/08 Notification of a joint venture (Case No IV/35.076 — Juli Motorenwerk) (l) 14 94/C 187/09 Notification of a joint venture (Case IV/35.098 — Gestetner-Ricoh) (') 15 1 ( l) Text with EEA relevance (Continued overleaf) Notice No Contents (continued) page 94/C 187/ 10 State aid — C 45 /93 (N 663 /93) — United Kingdom 16 Corrigenda 94/C 187/ 11 Corrigendum to the preliminary draft Commission Regulation (EC) of 30 September 1994 on the application of Article 85 (3) of the Treaty to certain categories of technology transfer agreements (OJ No C 178 , 30 .