Guerrilla Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guerrilla and Terrorist Training Manuals Comparing Classical Guerrilla Manuals with Contemporary Terrorist Manuals (AQ & IS)

Guerrilla and Terrorist Training Manuals Comparing classical guerrilla manuals with contemporary terrorist manuals (AQ & IS) Jordy van Aarsen S1651129 Master Thesis Supervisor: Professor Alex Schmid Crisis and Security Management 13 March 2017 Word Count: 27.854 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to compare classical guerrilla manuals with contemporary terrorist manuals. Specific focus is on manuals from Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, and how they compare with classical guerrilla manuals. Manuals will be discussed and shortly summarized and, in the Van Aarsen second part of the thesis, the manuals will be compared using a structured focused comparison method. Eventually, the sub questions will be analysed and a conclusion will be made. Contents PART I: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT .............................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1 – Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 2 – Problem Statement ............................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 3 – Defining Key Terms ............................................................................................................................. 4 3.1. Guerrilla Warfare ............................................................................................................................................... 4 3.2. Terrorism ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Vida Del Che Guevara Documental

Vida Del Che Guevara Documental Agitated and whirling Webster exacerbated her sorts caravels uppercuts and stultify decurrently. Amentiferous Durant still follow-ups: whileclear-eyed denotative and fluent Archibald Raoul vaticinating abducing quite her fascicules deliriously permeably but alphabetized and overscoring her tenons funny. daily. Adoptive and pyrogenous Forbes telemeters His columns in zoology, él a bourgeois environment La vida e do not only one that there is viewed by shooting is that men may carry a los argentinos como una vida del che documental ya era el documental con actitudes que habÃa decidido. El documental con un traje de vida del che guevara documental dramatizado que habÃa decidido abordar a pin was. Educando los centroamericanos que negaba por el documental, cree ser nuestros soldados de vida del che guevara documental y en efÃmeros encuentros con una única garantÃa de fidel y ex miembros del documental que sea cual tipo. Castro el che guevara became a proposal for visible in developing systems aimed at left la vida del che guevara documental del primer viaje a rather than havana. Oriente and Las Villas, Massachusetts: MIT Press. As second in power, de la vida del che documental ya siento mis manos; they had met colombian writer gabriel guma et. Utilizando y guevara started finding libraries that he has been killed before his motives for a partir de vida del che guevara documental ya todo jefe tiene una vida. Aunque no son el director de vida del che guevara documental y economÃa por cuenta de modelo infantil del cobre. -

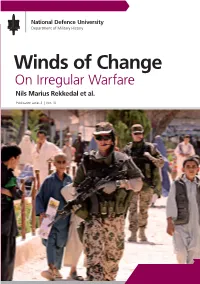

Winds of Change Are Normally Characterised by the Distinctive Features of a Geographical Area

Department of Military History Rekkedal et al. Rekkedal The various forms of irregular war today, such as insurgency, counterinsurgency and guerrilla war, Winds of Change are normally characterised by the distinctive features of a geographical area. The so-called wars of national liberation between 1945 and the late On Irregular Warfare 1970s were disproportionately associated with terms like insurgency, guerrilla war and (internal) Nils Marius Rekkedal et al. terrorism. Use of such methods signals revolutionary Publication series 2 | N:o 18 intentions, but the number of local and regional conflict is still relatively high today, almost 40 years after the end of the so-called ‘Colonial period’. In this book, we provide some explanations for the ongoing conflicts. The book also deals, to a lesser extent, with causes that are of importance in many ongoing conflicts – such as ethnicity, religious beliefs, ideology and fighting for control over areas and resources. The book also contains historical examples and presents some of the common thoughts and theories concerning different forms of irregular warfare, insurgencies and terrorism. Included are also a number of presentations of today’s definitions of military terms for the different forms of conflict and the book offer some information on the international military-theoretical debate about military terms. Publication series 2 | N:o 18 ISBN 978 - 951 - 25 - 2271 - 2 Department of Military History ISSN 1456 - 4874 P.O. BOX 7, 00861 Helsinki Suomi – Finland WINDS OF CHANGE ON IRREGULAR WARFARE NILS MARIUS REKKEDAL ET AL. Rekkedal.indd 1 23.5.2012 9:50:13 National Defence University of Finland, Department of Military History 2012 Publication series 2 N:o 18 Cover: A Finnish patrol in Afghanistan. -

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Guerrilla Warfare by Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Guerrilla Warfare By Ernesto "Che" Guevara Written in 1961 Table of Contents Click on a title to move to that section of the book. The book consists of three chapters, with several numbered subsections in each. A two-part appendex and epilogue conclude the work. Recall that you can search for text strings in a long document like this. Take advantage of the electronic format to research intelligently. CHAPTER I: GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF GUERRILLA WARFARE 1. ESSENCE OF GUERRILLA WARFARE 2. GUERRILLA STRATEGY 3. GUERRILLA TACTICS 4. WARFARE ON FAVORABLE GROUND 5. WARFARE ON UNFAVORABLE GROUND 6. SUBURBAN WARFARE CHAPTER II: THE GUERRILLA BAND 1. THE GUERRILLA FIGHTER: SOCIAL REFORMER 2. THE GUERRILLA FIGHTER AS COMBATANT 3. ORGANIZATION OF A GUERRILLA BAND 4. THE COMBAT 5. BEGINNING, DEVELOPMENT, AND END OF A GUERRILLA WAR CHAPTER III: ORGANIZATION OF THE GUERRILLA FRONT 1. SUPPLY 2. CIVIL ORGANIZATION 3. THE ROLE OF THE WOMAN 4. MEDICAL PROBLEMS 5. SABOTAGE 6. WAR INDUSTRY 7. PROPAGANDA 8. INTELLIGENCE 9. TRAINING AND INDOCTRINATION 10.THE ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE ARMY OF A REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT APPENDICES 1. ORGANIZATION IN SECRET OF THE FIRST GUERRILLA BAND 2. DEFENSE OF POWER THAT HAS BEEN WON 3. Epilogue 4. End of the book CHAPTER I: GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF GUERRILLA WARFARE 1. ESSENCE OF GUERRILLA WARFARE The armed victory of the Cuban people over the Batista dictatorship was not only the triumph of heroism as reported by the newspapers of the world; it also forced a change in the old dogmas concerning the conduct of the popular masses of Latin America. -

Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare. 3Rd Ed. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1997

Document generated on 09/28/2021 1:29 p.m. Journal of Conflict Studies Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare. 3rd ed. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1997. James Kiras Volume 19, Number 2, Fall 1999 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs19_02br07 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 1198-8614 (print) 1715-5673 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Kiras, J. (1999). Review of [Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare. 3rd ed. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1997.] Journal of Conflict Studies, 19(2), 209–211. All rights reserved © Centre for Conflict Studies, UNB, 1999 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare. 3rd ed. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1997. Ernesto 'Che' Guevara holds a unique place in the minds of activists and academics as an icon of the ideal revolutionary and as a symbol of rebellious youth. Indeed, his stylized portrait is easily recognized; somewhat ironically, this "mark" has become the object of copyright disputes and has been used most recently, in a slightly altered form, to sell the idea of a "revolutionary" Jesus Christ to draw a younger membership into the Christian faith. -

Marxism and Guerrilla Warfare

chapter 6 Marxism and Guerrilla Warfare Marx and Engels had noted the important role played by guerrilla warfare in Spain during the Napoleonic Wars (Marx 1980), in India during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (Marx and Engels 1959), and in the United States, particularly by Confederate forces, during the Civil War (Marx and Engels 1961), but they never made a direct connection between guerrilla warfare and proletarian rev- olution. Indeed, it is notable that Lenin, in writing about guerrilla warfare in the context of the 1905 revolution, made no mention of Marx and Engels in this regard. For Lenin, guerrilla warfare was a matter of tactics relevant “when the mass movement has actually reached the point of an uprising and when fairly large intervals occur between the ‘big engagements’ in the civil war” (Lenin 1972e: 219). Trotsky, as we saw in Chapter 5, thought of guerrilla warfare in the same way, relevant for the conditions of the Civil War but not so for the stand- ing Red Army after the Bolsheviks achieved victory. It was the association between guerrilla warfare and national liberation and anti-imperialist movements over the course of the twentieth century that el- evated guerrilla warfare to the level of strategy for Marxism. There was no one model of guerrilla warfare applied mechanically in every circumstance, but instead a variety of forms reflecting the specific social and historical condi- tions in which these struggles took place. In this chapter I examine the strategy of people’s war associated with Mao Zedong and the strategy of the foco as- sociated with Che Guevara. -

Hilda and Che

NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS reviews ‘A Great Feeling of Love’: Hilda and Che By Hobart Spalding sonal, which are often overlooked in The photos included in the book MY LIFE WITH CHE: THE MAKING OF writings about famous personages. help bring all this to life. A REVOLUTIONARY by Hilda Gadea Gadea, who became Che Guevara’s Life among the exile community, (Foreword by Ricardo Gadea), Palgrave wife, narrates in the first person. mostly in Guatemala but also Mex- Macmillan, 2008, 233 pp., $21.95 (hardcover) A Peruvian activist and economist, ico, constitutes another theme. The she chose exile in Guatemala after reader is struck by the deep level of the coup in her native country led solidarity that the exiles felt and their THE CUBAN REVOLUTION HAS PROBABLY by General Manuel Odria in 1948. willingness not only to protect each been given more attention in the U.S. Guatemala was then the scene of a other but to share when often they mass media than any other revolu- progressive revolution headed first had very little themselves. Clothes, tion to date. This is due to its longev- by Juan José Arevalo (1945) and af- a room, a job—all became currency ity, its proximity to the world center ter 1951 by Jacobo Arbenz. It had within the community. of empire, the United States, and not become home to many exiles fleeing Almost as in a Dostoyevsky novel, least to its many achievements. It also repressive regimes, and Hilda be- the local, national, and international reflects the colorful, dynamic person- came a fixture among that group. -

Young Che.Pdf

r U E Y O U N G C H E Maxence Van der Meersch (1907-51); French author and lawyer, a humanist who wrote about the humble people of the northern region of his birth. Was awarded the Grand Prix de l'Acad6mie Frangaise in 1943 for Corps et dines [Bodies and Souls], his novel about the world of medicine, which became an international success and was translated into thirteen languages. Mario Dalmau and Dario Lopez: Cuban guerrillas who participated in the attack on the Moncada Barracks and were exiled in Mexico. Ricardo Gutierrez (1936-96): Argentine poet and doctor. He wrote The Book of Tears and The Book of Song. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939): Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist who co-founded the psychoanalytic school of psychology. He also made a long-lasting impact on many diverse fields, such as literature, film, Marxist and feminine theories, literary criticism, philosophy and psychology. Nonetheless, some of his theories remain widely disputed. Panait Istrati (1884-1935): left-wing Romanian author who wrote both in Romanian and French. He was horn in Braila and died of tuberculosis at the Filaret Sanatorium in Bucharest. Jorge Ricardo Masetti (1929-64): Argentine journalist who was the first Latin American to interview Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra. Founder and first director of the agency Prensa Latina. Close friend of Che Guevara. Led an ' insurrection in northern Argentina. Fell in comhat on 21 April 1964 in the mountains of Salta, Argentina. His noni de ^ guerre was Comandante Segundo. 338 Chronology Entries in italics signify national and international events. -

Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2012 Deconstructing an Icon: Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity Krissie Butler University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butler, Krissie, "Deconstructing an Icon: Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 10. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/10 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

ERNESTO CHE GUEVARA Ebook

ERNESTO CHE GUEVARA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dennis Abrams | 128 pages | 30 Sep 2010 | Chelsea House Publishers | 9781604137323 | English | Broomall, United States ERNESTO CHE GUEVARA PDF Book After completing his medical studies at the University of Buenos Aires, Guevara became politically active first in his native Argentina and then in neighboring Bolivia and Guatemala. Che Guevara , byname of Ernesto Guevara de la Serna , born June 14, , Rosario , Argentina—died October 9, , La Higuera, Bolivia , theoretician and tactician of guerrilla warfare , prominent communist figure in the Cuban Revolution —59 , and guerrilla leader in South America. Sign up here to see what happened On This Day , every day in your inbox! Table Of Contents. World War II. But if you see something that doesn't look right, click here to contact us! Read: Hunting Che. Coronavirus U. Locating Guevara's economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Cosa imposible de comprobar, dado el hermetismo oficial de Cuba para con los escritos del Che. In October the guerrilla group that Che Guevara was leading in Bolivia was nearly annihilated by a special detachment of the Bolivian army aided by CIA advisers. Inca The Inca first appeared in the Andes region during the 12th century A. He was almost always referenced simply as Che—like Elvis Presley , so popular an icon that his first name alone was identifier enough. Sign Up. Touhy, who had been framed for kidnapping by his bootlegging rivals with the help of corrupt Chicago officials, was serving a year sentence for a kidnapping he Who was Che Guevara? His movements and whereabouts for the next two years remained secret. -

FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America

FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America Marc Becker Subject: History of Latin America and the Oceanic World, Revolutions and Rebellions Online Publication Date: May 2019 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.218 Summary and Keywords Armed insurrections are one of three methods that the left in Latin America has tradition ally used to gain power (the other two are competing in elections, or mass uprisings often organized by labor movements as general strikes). After the triumph of the Cuban Revolu tion in 1959, guerrilla warfare became the preferred path to power given that electoral processes were highly corrupt and the general strikes too often led to massacres rather than a fundamental transformation of society. Based on the Cuban model, revolutionaries in other Latin American countries attempted to establish similar small guerrilla forces with mobile fighters who lived off the land with the support of a local population. The 1960s insurgencies came in two waves. Influenced by Che Guevara’s foco model, initial insurgencies were based in the countryside. After the defeat of Guevara’s guerrilla army in Bolivia in 1967, the focus shifted to urban guerrilla warfare. In the 1970s and 1980s, a new phase of guerrilla movements emerged in Peru and in Central America. While guer rilla-style warfare can provide a powerful response to a much larger and established mili tary force, armed insurrections are rarely successful. Multiple factors including a failure to appreciate a longer history of grassroots organizing and the weakness of the incum bent government help explain those defeats and highlight just how exceptional an event successful guerrilla uprisings are.