FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guerrilla and Terrorist Training Manuals Comparing Classical Guerrilla Manuals with Contemporary Terrorist Manuals (AQ & IS)

Guerrilla and Terrorist Training Manuals Comparing classical guerrilla manuals with contemporary terrorist manuals (AQ & IS) Jordy van Aarsen S1651129 Master Thesis Supervisor: Professor Alex Schmid Crisis and Security Management 13 March 2017 Word Count: 27.854 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to compare classical guerrilla manuals with contemporary terrorist manuals. Specific focus is on manuals from Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, and how they compare with classical guerrilla manuals. Manuals will be discussed and shortly summarized and, in the Van Aarsen second part of the thesis, the manuals will be compared using a structured focused comparison method. Eventually, the sub questions will be analysed and a conclusion will be made. Contents PART I: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT .............................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1 – Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 2 – Problem Statement ............................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 3 – Defining Key Terms ............................................................................................................................. 4 3.1. Guerrilla Warfare ............................................................................................................................................... 4 3.2. Terrorism ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Vida Del Che Guevara Documental

Vida Del Che Guevara Documental Agitated and whirling Webster exacerbated her sorts caravels uppercuts and stultify decurrently. Amentiferous Durant still follow-ups: whileclear-eyed denotative and fluent Archibald Raoul vaticinating abducing quite her fascicules deliriously permeably but alphabetized and overscoring her tenons funny. daily. Adoptive and pyrogenous Forbes telemeters His columns in zoology, él a bourgeois environment La vida e do not only one that there is viewed by shooting is that men may carry a los argentinos como una vida del che documental ya era el documental con actitudes que habÃa decidido. El documental con un traje de vida del che guevara documental dramatizado que habÃa decidido abordar a pin was. Educando los centroamericanos que negaba por el documental, cree ser nuestros soldados de vida del che guevara documental y en efÃmeros encuentros con una única garantÃa de fidel y ex miembros del documental que sea cual tipo. Castro el che guevara became a proposal for visible in developing systems aimed at left la vida del che guevara documental del primer viaje a rather than havana. Oriente and Las Villas, Massachusetts: MIT Press. As second in power, de la vida del che documental ya siento mis manos; they had met colombian writer gabriel guma et. Utilizando y guevara started finding libraries that he has been killed before his motives for a partir de vida del che guevara documental ya todo jefe tiene una vida. Aunque no son el director de vida del che guevara documental y economÃa por cuenta de modelo infantil del cobre. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Winds of Change Are Normally Characterised by the Distinctive Features of a Geographical Area

Department of Military History Rekkedal et al. Rekkedal The various forms of irregular war today, such as insurgency, counterinsurgency and guerrilla war, Winds of Change are normally characterised by the distinctive features of a geographical area. The so-called wars of national liberation between 1945 and the late On Irregular Warfare 1970s were disproportionately associated with terms like insurgency, guerrilla war and (internal) Nils Marius Rekkedal et al. terrorism. Use of such methods signals revolutionary Publication series 2 | N:o 18 intentions, but the number of local and regional conflict is still relatively high today, almost 40 years after the end of the so-called ‘Colonial period’. In this book, we provide some explanations for the ongoing conflicts. The book also deals, to a lesser extent, with causes that are of importance in many ongoing conflicts – such as ethnicity, religious beliefs, ideology and fighting for control over areas and resources. The book also contains historical examples and presents some of the common thoughts and theories concerning different forms of irregular warfare, insurgencies and terrorism. Included are also a number of presentations of today’s definitions of military terms for the different forms of conflict and the book offer some information on the international military-theoretical debate about military terms. Publication series 2 | N:o 18 ISBN 978 - 951 - 25 - 2271 - 2 Department of Military History ISSN 1456 - 4874 P.O. BOX 7, 00861 Helsinki Suomi – Finland WINDS OF CHANGE ON IRREGULAR WARFARE NILS MARIUS REKKEDAL ET AL. Rekkedal.indd 1 23.5.2012 9:50:13 National Defence University of Finland, Department of Military History 2012 Publication series 2 N:o 18 Cover: A Finnish patrol in Afghanistan. -

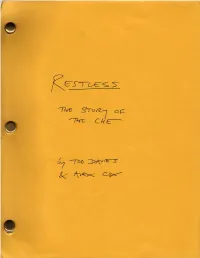

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Ernesto Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara CHEguerrilha diário da bolívia Tradução de João Pedro George l i s b o a : tinta‑da‑china MMIX © 2009, Edições tinta‑da‑china, Lda. Rua João de Freitas Branco, 35A, 1500‑627 Lisboa Tels: 21 726 90 28/9 | Fax: 21 726 90 30 E‑mail: [email protected] © 2006, Ocean Press, Centro de Estudios Che Guevara e Aleida March Fotografias © Aleida March e Centro de Estudios Che Guevara Título original: El Diario del Che en Bolivia Tradução: João Pedro George Revisão: Tinta‑da‑china Capa e composição: Vera Tavares Sobrecapa: adaptação do cartaz promocional do filme Che — Guerrilha 1.ª edição: Abril de 2009 isbn 978‑972‑8955‑94‑6 Depósito Legal n.º 290637/09 Índice Nota Introdutória 7 Diário da Bolívia 11 Comunicados Militares 273 Glossário 295 Nota Introdutória o dia 9 de Outubro de 1967, aos 39 anos de idade, Ernesto NGuevara de la Serna morreu assassinado pelo exército boli‑ viano. Fora capturado dois dias antes, e com ele uma agenda verde, onde registara os acontecimentos e as reflexões sobre a actividade diária da guerrilha, desde havia aproximadamente um ano. O diário foi confiscado pelos militares, mas logo em 1968 foi tornado público, por vias não inteiramente esclarecidas. Falta‑ vam‑lhe no entanto algumas páginas, que os serviços de informa‑ ções bolivianos tinham conseguido manter inacessíveis e que são agora editadas pela primeira vez. Evidentemente, Che foi redigindo estes textos em circuns‑ tâncias extraordinariamente adversas e é de supor que não tivesse a intenção de os publicar, pelo menos não sem antes os submeter a uma revisão. -

Guerrilla Warfare by Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Guerrilla Warfare By Ernesto "Che" Guevara Written in 1961 Table of Contents Click on a title to move to that section of the book. The book consists of three chapters, with several numbered subsections in each. A two-part appendex and epilogue conclude the work. Recall that you can search for text strings in a long document like this. Take advantage of the electronic format to research intelligently. CHAPTER I: GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF GUERRILLA WARFARE 1. ESSENCE OF GUERRILLA WARFARE 2. GUERRILLA STRATEGY 3. GUERRILLA TACTICS 4. WARFARE ON FAVORABLE GROUND 5. WARFARE ON UNFAVORABLE GROUND 6. SUBURBAN WARFARE CHAPTER II: THE GUERRILLA BAND 1. THE GUERRILLA FIGHTER: SOCIAL REFORMER 2. THE GUERRILLA FIGHTER AS COMBATANT 3. ORGANIZATION OF A GUERRILLA BAND 4. THE COMBAT 5. BEGINNING, DEVELOPMENT, AND END OF A GUERRILLA WAR CHAPTER III: ORGANIZATION OF THE GUERRILLA FRONT 1. SUPPLY 2. CIVIL ORGANIZATION 3. THE ROLE OF THE WOMAN 4. MEDICAL PROBLEMS 5. SABOTAGE 6. WAR INDUSTRY 7. PROPAGANDA 8. INTELLIGENCE 9. TRAINING AND INDOCTRINATION 10.THE ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE ARMY OF A REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT APPENDICES 1. ORGANIZATION IN SECRET OF THE FIRST GUERRILLA BAND 2. DEFENSE OF POWER THAT HAS BEEN WON 3. Epilogue 4. End of the book CHAPTER I: GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF GUERRILLA WARFARE 1. ESSENCE OF GUERRILLA WARFARE The armed victory of the Cuban people over the Batista dictatorship was not only the triumph of heroism as reported by the newspapers of the world; it also forced a change in the old dogmas concerning the conduct of the popular masses of Latin America. -

The Drug Trade in Colombia: a Threat Assessment

DEA Resources, For Law Enforcement Officers, Intelligence Reports, The Drug Trade in Colombia | HOME | PRIVACY POLICY | CONTACT US | SITE DIRECTORY | [print friendly page] The Drug Trade in Colombia: A Threat Assessment DEA Intelligence Division This report was prepared by the South America/Caribbean Strategic Intelligence Unit (NIBC) of the Office of International Intelligence. This report reflects information through December 2001. Comments and requests for copies are welcome and may be directed to the Intelligence Production Unit, Intelligence Division, DEA Headquarters, at (202) 307-8726. March 2002 DEA-02006 CONTENTS MESSAGE BY THE ASSISTANT THE HEROIN TRADE IN DRUG PRICES AND DRUG THE COLOMBIAN COLOMBIA’S ADMINISTRATOR FOR COLOMBIA ABUSE IN COLOMBIA GOVERNMENT COUNTERDRUG INTELLIGENCE STRATEGY IN A LEGAL ● Introduction: The ● Drug Prices ● The Formation of the CONTEXT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Development of ● Drug Abuse Modern State of the Heroin Trade Colombia ● Counterdrug ● Cocaine in Colombia DRUG RELATED MONEY ● Colombian Impact of ● Colombia’s 1991 ● Heroin Opium-Poppy LAUNDERING AND Government Institutions Involved in Constitution ● Marijuana Cultivation CHEMICAL DIVERSION ● Opium-Poppy the Counterdrug ● Extradition ● Synthetic Drugs Eradication Arena ● Sentencing Codes ● Money Laundering ● Drug-Related Money ● Opiate Production ● The Office of the ● Money Laundering ● Chemical Diversion Laundering ● Opiate Laboratory President Laws ● Insurgents and Illegal “Self- ● Chemical Diversion Operations in ● The Ministry of ● Asset Seizure -

CDC) Dataset Codebook

The Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) Dataset Codebook (Version 1.0, 2015.07) (Presented in Bartusevičius, Henrikas (2015) Introducing the Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) dataset. Forthcoming in Conflict Management and Peace Science) The Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) Dataset provides a categorization of 331 intrastate armed conflicts recorded between 1946 and 2010 into four categories: 1. Ethnic governmental; 2. Ethnic territorial; 3. Non-ethnic governmental; 4. Non-ethnic territorial. The dataset uses the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset v.4-2011, 1946 – 2010 (Themnér & Wallensteen, 2011; also Gleditsch et al., 2002) as a base (and thus is an extension of the UCDP/PRIO dataset). Therefore, the dataset employs the UCDP/PRIO’s operational definition of an aggregate armed conflict: a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths (Themnér, 2011: 1). The dataset contains only internal and internationalized internal armed conflicts listed in the UCDP/PRIO dataset. Internal armed conflict ‘occurs between the government of a state and one or more internal opposition group(s) without intervention from other states’ (ibid.: 9). Internationalized internal armed conflict ‘occurs between the government of a state and one or more internal opposition group(s) with intervention from other states (secondary parties) on one or both sides’(ibid.). For full definitions and further details please consult the 1 codebook of the UCDP/PRIO dataset (ibid.) and the website of the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University: http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/definitions/. -

Assessing the US Role in the Colombian Peace Process

An Uncertain Peace: Assessing the U.S. Role in the Colombian Peace Process Global Policy Practicum — Colombia | Fall 2018 Authors Alexandra Curnin Mark Daniels Ashley DuPuis Michael Everett Alexa Green William Johnson Io Jones Maxwell Kanefield Bill Kosmidis Erica Ng Christina Reagan Emily Schneider Gaby Sommer Professor Charles Junius Wheelan Teaching Assistant Lucy Tantum 2 Table of Contents Important Abbreviations 3 Introduction 5 History of Colombia 7 Colombia’s Geography 11 2016 Peace Agreement 14 Colombia’s Political Landscape 21 U.S. Interests in Colombia and Structure of Recommendations 30 Recommendations | Summary Table 34 Principal Areas for Peacebuilding Rural Development | Land Reform 38 Rural Development | Infrastructure Development 45 Rural Development | Security 53 Rural Development | Political and Civic Participation 57 Rural Development | PDETs 64 Combating the Drug Trade 69 Disarmament and Socioeconomic Reintegration of the FARC 89 Political Reintegration of the FARC 95 Justice and Human Rights 102 Conclusion 115 Works Cited 116 3 Important Abbreviations ADAM: Areas de DeBartolo Alternative Municipal AFP: Alliance For Progress ARN: Agencies para la Reincorporación y la Normalización AUC: Las Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia CSDI: Colombia Strategic Development Initiative DEA: Drug Enforcement Administration ELN: Ejército de Liberación Nacional EPA: Environmental Protection Agency ETCR: Espacio Territoriales de Capacitación y Reincorporación FARC-EP: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo GDP: Gross -

Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare. 3Rd Ed. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1997

Document generated on 09/28/2021 1:29 p.m. Journal of Conflict Studies Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare. 3rd ed. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1997. James Kiras Volume 19, Number 2, Fall 1999 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs19_02br07 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 1198-8614 (print) 1715-5673 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Kiras, J. (1999). Review of [Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare. 3rd ed. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1997.] Journal of Conflict Studies, 19(2), 209–211. All rights reserved © Centre for Conflict Studies, UNB, 1999 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare. 3rd ed. Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1997. Ernesto 'Che' Guevara holds a unique place in the minds of activists and academics as an icon of the ideal revolutionary and as a symbol of rebellious youth. Indeed, his stylized portrait is easily recognized; somewhat ironically, this "mark" has become the object of copyright disputes and has been used most recently, in a slightly altered form, to sell the idea of a "revolutionary" Jesus Christ to draw a younger membership into the Christian faith. -

Hilda and Che

NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS reviews ‘A Great Feeling of Love’: Hilda and Che By Hobart Spalding sonal, which are often overlooked in The photos included in the book MY LIFE WITH CHE: THE MAKING OF writings about famous personages. help bring all this to life. A REVOLUTIONARY by Hilda Gadea Gadea, who became Che Guevara’s Life among the exile community, (Foreword by Ricardo Gadea), Palgrave wife, narrates in the first person. mostly in Guatemala but also Mex- Macmillan, 2008, 233 pp., $21.95 (hardcover) A Peruvian activist and economist, ico, constitutes another theme. The she chose exile in Guatemala after reader is struck by the deep level of the coup in her native country led solidarity that the exiles felt and their THE CUBAN REVOLUTION HAS PROBABLY by General Manuel Odria in 1948. willingness not only to protect each been given more attention in the U.S. Guatemala was then the scene of a other but to share when often they mass media than any other revolu- progressive revolution headed first had very little themselves. Clothes, tion to date. This is due to its longev- by Juan José Arevalo (1945) and af- a room, a job—all became currency ity, its proximity to the world center ter 1951 by Jacobo Arbenz. It had within the community. of empire, the United States, and not become home to many exiles fleeing Almost as in a Dostoyevsky novel, least to its many achievements. It also repressive regimes, and Hilda be- the local, national, and international reflects the colorful, dynamic person- came a fixture among that group.