Book Reviews | Reseñas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

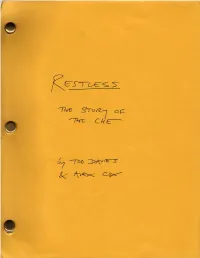

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Ernesto Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara CHEguerrilha diário da bolívia Tradução de João Pedro George l i s b o a : tinta‑da‑china MMIX © 2009, Edições tinta‑da‑china, Lda. Rua João de Freitas Branco, 35A, 1500‑627 Lisboa Tels: 21 726 90 28/9 | Fax: 21 726 90 30 E‑mail: [email protected] © 2006, Ocean Press, Centro de Estudios Che Guevara e Aleida March Fotografias © Aleida March e Centro de Estudios Che Guevara Título original: El Diario del Che en Bolivia Tradução: João Pedro George Revisão: Tinta‑da‑china Capa e composição: Vera Tavares Sobrecapa: adaptação do cartaz promocional do filme Che — Guerrilha 1.ª edição: Abril de 2009 isbn 978‑972‑8955‑94‑6 Depósito Legal n.º 290637/09 Índice Nota Introdutória 7 Diário da Bolívia 11 Comunicados Militares 273 Glossário 295 Nota Introdutória o dia 9 de Outubro de 1967, aos 39 anos de idade, Ernesto NGuevara de la Serna morreu assassinado pelo exército boli‑ viano. Fora capturado dois dias antes, e com ele uma agenda verde, onde registara os acontecimentos e as reflexões sobre a actividade diária da guerrilha, desde havia aproximadamente um ano. O diário foi confiscado pelos militares, mas logo em 1968 foi tornado público, por vias não inteiramente esclarecidas. Falta‑ vam‑lhe no entanto algumas páginas, que os serviços de informa‑ ções bolivianos tinham conseguido manter inacessíveis e que são agora editadas pela primeira vez. Evidentemente, Che foi redigindo estes textos em circuns‑ tâncias extraordinariamente adversas e é de supor que não tivesse a intenção de os publicar, pelo menos não sem antes os submeter a uma revisão. -

Como Ernestito, El Corajudo

Un gigante moral que crece Pág. 5 www.vanguardia.cu Santa Clara, 16 de junio de 2018 Precio: 0.20 ÓRGANO OFICIAL DEL COMITÉ PROVINCIAL DEL PARTIDO EN VILLA CLARA Como Ernestito, el corajudo Pienso en él, en el estereoti- Por Mercedes Rodríguez García Foto: SMB porque el «comandante Gueva- po que pueda formarse por la ra no hacía bandera de ser un reiteración de fotos, anécdotas, corajudo, ni le parecía impor- por las invariables efemérides tante tener el coraje convencio- celebradas casi siempre de nal. Él tenía un coraje austero, la misma forma, en el mismo el de la madre».(2) lugar, a la misma hora. Por ello, está bien expresar Por eso trato de encontrar los con fuerza, fi rmeza y justeza: rasgos primigenios. No aquellos ¡Seremos como el Che! que puedan emanar de sus an- Como el Che hombre, y como cestros, entre los que se cuentan el Che Ernestito. El niño que se —por línea materna— un virrey convertiría en leyenda. Un poco de España y buscadores de oro. genioso, pero un niño solida- Tampoco me interesan los rio, generoso, arriesgado, que del mítico rostro captado un siempre decía lo que pensaba día tremendísimo de duelo, con y nunca dejó de hacer lo que boina, melena, barba y jacket decía. ajustado al cuello, un frío y Un hombre que como padre, nublado octubre «kordasiano», a lo largo de la vida, no pudo que aún recorre el mundo en dedicar mucho tiempo a sus hi- afi ches, pancartas y carteles. jos, pues siempre dio prioridad Este mundo maltrecho, olvida- a las tareas en la dirección del do de afectos y lleno de renco- país que lo adoptó y nacionalizó res. -

FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America

FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History FARC, Shining Path, and Guerillas in Latin America Marc Becker Subject: History of Latin America and the Oceanic World, Revolutions and Rebellions Online Publication Date: May 2019 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.218 Summary and Keywords Armed insurrections are one of three methods that the left in Latin America has tradition ally used to gain power (the other two are competing in elections, or mass uprisings often organized by labor movements as general strikes). After the triumph of the Cuban Revolu tion in 1959, guerrilla warfare became the preferred path to power given that electoral processes were highly corrupt and the general strikes too often led to massacres rather than a fundamental transformation of society. Based on the Cuban model, revolutionaries in other Latin American countries attempted to establish similar small guerrilla forces with mobile fighters who lived off the land with the support of a local population. The 1960s insurgencies came in two waves. Influenced by Che Guevara’s foco model, initial insurgencies were based in the countryside. After the defeat of Guevara’s guerrilla army in Bolivia in 1967, the focus shifted to urban guerrilla warfare. In the 1970s and 1980s, a new phase of guerrilla movements emerged in Peru and in Central America. While guer rilla-style warfare can provide a powerful response to a much larger and established mili tary force, armed insurrections are rarely successful. Multiple factors including a failure to appreciate a longer history of grassroots organizing and the weakness of the incum bent government help explain those defeats and highlight just how exceptional an event successful guerrilla uprisings are. -

Young Ernesto Guevara and the Myth of Che Dan Sprinkle Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2012 Young Ernesto Guevara and the Myth of Che Dan Sprinkle Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Sprinkle, Dan, "Young Ernesto Guevara and the Myth of Che" (2012). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 256. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/256 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Young Ernesto Guevara and the Myth of Che Dan Sprinkle HST 499: Senior Seminar Spring 2012 First Reader: Dr. John Rector Second Reader: Dr. Max Geier June 6, 2012 1 Ernesto “Che” Guevara de la Serna is constantly dramatized and idolized for the things he did later in his life in the Congo, Guatemala, Cuba, and Bolivia pertaining to socialist revolution. The historical events Che partook in have been studied for decades by historians around the world and no consensus has been reached as to the morality of his actions. Many people throughout Latin America view Guevara as a heroic martyr for the people, whereas many people from the rest of the world see him as little more than a terrorist. What many of these historians fail to address is what exactly made Ernesto Guevara leave his relatively upper-middle class, loving family behind to pursue a life of revolution and guerrilla warfare. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós-Graduação Em Inglês: Estudos Linguísticos E Literários

i UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM INGLÊS: ESTUDOS LINGUÍSTICOS E LITERÁRIOS Olegario da Costa Maya Neto ACTUALIZING CHE'S HISTORY: CHE GUEVARA'S ENDURING RELEVANCE THROUGH FILM Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Inglês: Estudos Linguísticos e Literários da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Letras. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Anelise Reich Corseuil Florianópolis 2017 ii iii iv v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank my parents, Nadia and Ahyr Maya, who have always supported me and stimulated my education. Since the early years of learning how to read and write, I knew I could always rely on them. I would also like to thank my companion and best friend, Ruth Zanini. She patiently listened to me whenever I had a new insight or when I was worried. She gave me advices when I needed them and also took care of my share of the housework when I was busy. In addition, I would like to thank my brother Ahyr, who has always been a source of inspiration and advice for me. And I would like to thank my friends, especially Fabio Coura, Marcelo Barreto and Renato Muchiuti, who were vital in keeping my spirits high during the whole Master's Course. I would also like to thank all teachers and professors who for the past twenty six years have helped me learn. Unfortunately, they are too many to fit in a single page and I do not want to risk forgetting someone. Nonetheless, I would like to acknowledge their contribution. -

Ensayo Contra El Mito Del Che Guevara

Ensayo contra el mito del Che Guevara JUAN JOSÉ SEBRELI Durante su asistencia a la Feria del Libro de Frankfurt, la presidenta Cristina Kirchner erigió como iconos de su país, Argentina, a cuatro personajes: Carlos Gardel, Evita de Perón, el Che Guevara y Diego Armando Maradona. Efectivamente, los cuatro integran hoy el panteón nacional de los mitos populares argentinos, de los cuales tres encarnan las pasiones de ese singular pueblo: el tango, el peronismo y el fútbol. Esta conjunción ya había motivado al sociólogo argentino Juan José Sebreli a emprender una investigación sobre esos cuatro iconos, cuyo resultado –Comediantes 50 y mártires: ensayo contra los mitos– obtuvo en el año 2008 el primer premio de ensayo de Casa de América y Editorial Debate. Un jurado integrado por Carlos Monsiváis, Edmundo Paz Soldán, Sol Gallego Díaz, Miguel Barroso y Miguel Aguilar pronunció por unanimidad esta decisión. Por la calidad de esta demolición crítica de mitos popu- lares es que se ofrece el quinto capítulo de esa obra al lector ilustrado de Santander, un ejemplo de las nuevas perspectivas del análisis sociológico latinoamericano que supera las beaterías de la década de los años sesenta del siglo XX, cuando los intelectuales po- pulistas proclamaron que sólo la comunión con la sensibilidad popular permitía percibir la emoción de los mitos populares. A diferencia de la aspiración a la universalidad de las representaciones científicas, los mitos dependen de una comunidad de creyentes que los fundan en los sentimientos particulares ajenos a la racionalidad. Los creyentes en mitos no se arriesgan a analizarlos porque su fe inhibe el uso de su razón, dado que han suspendido su capacidad crítica, pero los políticos profesionales los pervierten al usarlos como instrumentos de movilización de masas. -

Diarios De Motocicleta N O T a S DE UN V I a J E P O R a M É R I C a L a T I N A

Diarios de motocicleta N O T A S DE UN V I A J E P O R A M É R I C A L A T I N A LLEVADO AL CINE POR WALTER SALLES Y ROBERT REDFORD Planeta Todo los trascendente de nuestra empresa se nos escapaba en ese momento, solo veíamos el polvo del camino y nosotros sobre la moto devorando kilómetros en la fuga hacia el norte. ERNESTO CHE GUEVARA Nueva edición ampliada Prólogo a la edición por Aleida Guevara Diarios de motocicleta ERNESTO CHE GUEVARA Vivido y entretenido diario de viaje del Joven Che. Esta nueva edición incluye fotografías inéditas tomadas por Ernesto a los 23 años, durante su travesía por el continente, y está presentada con un tierno prólogo de Aleida Guevara, quien ofrece una perspectiva distinta de su padre, el hom- bre y el icono de millones de personas. "Un viaje, una cantidad de viajes. Ernesto Guevara en busca de aven- turas, Ernesto Guevara en busca de América, Ernesto Guevara en busca del Che. En este recorrido de recorridos, la soledad se unió a la solidaridad, el 'yo' se convirtió en 'nosotros'." —EDUARDO GALEANO "Nuestro film es sobre un hombre joven, el Che, pleno de amor por el continente y buscando su lugar en él." —WALTER SALLES, DIRECTOR DE LA PELÍCULA DIARIOS DE MOTOCICLETA Publicado en acuerdo con el Centro de Estudios de Ernesto,Che Guevara, La Habana, Cuba ISBN 950-49-1202-8 "Das Kapital se encuentra con Easy Rider." TIMES "Un James Dean o Jack Kerouac latinoamericano." WASHINGTON POST "Un extraordinario relato en primera persona. -

COCKTAIL / P.27 / Enlighten and Inspire

The Cuban Revolution was about more than the removal of the Batista regime. Its goal was the complete political, social and cultural transformation of a nation. Central to that vision were women – who ran underground networks, managed information and, ultimately, fought alongside their brothers. This is their story. WELCOME TO BLACKTAIL. CONTENTS VILMA ESPÍN- HELPING TO SHAPE 01. DRINKS LIST 02. A REVOLUTION WITHIN A REVOLUTION The daughter of two major figures of the Prices do not include 8.875% NYS Sales Tax. Revolution tells the story of her mother’s role A discretionary 20% service charge will be in creating a new and better Cuba for all women. added to all parties of 5 or more. // Mariela Castro Espín / p.35 / HIGHBALL / p.03 / A LITTLE PIECE OF MY LIFE - 03. A DAUGHTER’S REMINISCENCES What was it like growing up the child of PUNCH / p.09 / an icon of the Revolution? Che Guevara’s daughter recalls the lessons passed on by the father she lost. // Aleida Guevara March / p.49/ SOUR / p.15 / THE CUBAN POSTER - OLD-FASHIONED / p.21 / 04. PRIDE AND DETERMINATION An eminent authority on Cuban poster art discusses the role this medium played in an era before mass communication to encourage, COCKTAIL / p.27 / enlighten and inspire. // Lincoln Cushing / p.65 / / BLACKTAIL / 01 / Drinks List / ARRIVAL, BLOOD & SHADOWS FALL 1952 Elections are coming. But there are also rumors of another imminent arrival. Fulgencio Batista is returning from self- imposed exile in the United States. The former president is coming to lay claim to the island once again. -

Che Cronología

Ernesto Che Guevara. Cronología Si bien en su certificado de nacimiento constaba que Ernesto Guevara de la Serna había nacido el 14 de junio de 1928 su madre confesó treinta años mas tarde que Ernesto había nacido el 14 de mayo de 1928. 1928 14 de mayo. En la ciudad de Rosario, Argentina, nace Ernesto Guevara de la Serna, primer hijo de Ernesto Guevara Lynch y Celia de la Serna. 1929 Viven en la provincia de Misiones, donde la familia tiene un yerbatal. Nace su hermana Celia. 1930 Mayo. Ernesto sufre su primer ataque de asma. Le diagnostican afección asmática severa. 1932 La familia se radica en Bs As. Nace su hermano Roberto. 1933 Junio. Se trasladan a Alta Gracia, un pueblo en las Sierras Cordobesas, de clima propicio para los enfermos del sistema respiratorio. Vivirán alli hasta 1943. 1934 28 de enero. Nace su hermana Ana María. 1936 Estalla la guerra civil española. Su tío Córdova Ituburu es corresponsal de guerra del diario Crítica. Es la primera aproximación de Ernesto a la política. 1943 Vive en Córdoba. Concluye la escuela secundaria. Comienza una amistad con los hermanos Granado y los hermanos Ferrer. Nace su último hermano Juan Martin. CEME - Centro de Estudios Miguel Enríquez - Archivo Chile 1945 Se trasladan a Bs As. Ingresa a la facultad de medicina. Conoce a Tita Infante. Trabaja para pagarse la carrera. 1950 1 de enero. Recorre mas de 4500 km. del norte argentino con una bicicleta, a la cual le adosa un pequeño motor. Se detiene en el leprosario del Chañar. Trabaja en vialidad y en la flota mercante argentina. -

Guevarism - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

مذهب جيفارا Guevarism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guevarism Guevarism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Guevarism is a theory of communist revolution and a military strategy of guerrilla warfare associated with Marxist revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara, a leading figure of the Cuban Revolution. During the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union clashed in a series of proxy wars, especially in the developing nations of the Third World, including many decolonization struggles. Contents 1 Overview 2 Criticism 3 See also 4 Notes Overview After the 1959 triumph of the Cuban insurrection led by a militant "foco" under Fidel Castro, his Argentina-born, cosmopolitan and Marxist colleague Guevara parlayed his ideology and experiences into a model for emulation (and at times, direct military intervention) around the globe. While exporting one such "focalist" revolution to Bolivia, leading an armed vanguard party there in October 1967, Guevara was captured and executed, becoming a martyr to both the World Communist Movement and the New Left. His ideology promotes exporting revolution to any country whose leader is supported by the empire (United States) and has fallen out of favor with its citizens. Guevara talks about how constant guerrilla warfare taking place in non-urban areas can overcome leaders. He introduces three points that are representative of his ideology as a whole: that the people can win with proper organization against a nation's army; that the conditions that make a revolution possible can be put in place by the popular forces; and that the popular forces always have an advantage in a non urban setting.