By Che Guevara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

El Ejército En El Poder. La “Revolución Peruana” Un Ensayo De “Revolución Nacional”

GUILLERMO MARTÍN CAVIASCA - E L EJÉRCITO EN EL PODER . L A “R EVOLUCIÓN PERUANA ”... El ejército en el poder. La “Revolución Peruana” un ensayo de “Revolución nacional”. The army in power. The "Peruvian Revolution" an essay on "National Revolution". por Guillermo Martín Caviasca* Recibido: 15/10/2017 - Aprobado: 4/4/2018 Resumen Desde el año 1968 hasta 1975 se desarrolló en el Perú la denominada “Revolución peruana”. Fue un proceso político iniciado a partir de un golpe H C militar en el marco de las dictaduras de la década de 1960 que partían de T U T A P D : / E / R P la necesidad de lograr la “seguridad nacional”. Sin embargo los militares N U O B S L I D C peruanos gobernaron haciendo explícita su intención de “nacionalizar la E A C M I O A N R economía”, “romper con la dependencia” y “fomentar la participación popu - E T S E . S / O A C lar”. Así se dio lugar a un gran debate en la izquierda argentina en torno a Ñ I A O L E 9 S , . la relación de los revolucionarios con los militares que adscribían a estas U N B R A O . A R ideas en Latinoamérica y en el propio país, como también sobre la verda - 1 / 4 I , N E D N E dera naturaleza revolucionaria de esos militares. X E R . P O H - P J U / C N U I O A D 2 “Revolución nacional” - peruanismo - Velasco Alvarado E Palabras Clave: 0 R 1 N 8 O S Ejércitos latinoamericanos - Seguridad nacional. -

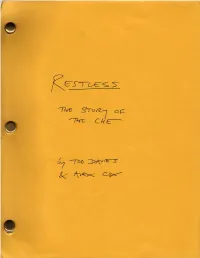

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Ernesto Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara CHEguerrilha diário da bolívia Tradução de João Pedro George l i s b o a : tinta‑da‑china MMIX © 2009, Edições tinta‑da‑china, Lda. Rua João de Freitas Branco, 35A, 1500‑627 Lisboa Tels: 21 726 90 28/9 | Fax: 21 726 90 30 E‑mail: [email protected] © 2006, Ocean Press, Centro de Estudios Che Guevara e Aleida March Fotografias © Aleida March e Centro de Estudios Che Guevara Título original: El Diario del Che en Bolivia Tradução: João Pedro George Revisão: Tinta‑da‑china Capa e composição: Vera Tavares Sobrecapa: adaptação do cartaz promocional do filme Che — Guerrilha 1.ª edição: Abril de 2009 isbn 978‑972‑8955‑94‑6 Depósito Legal n.º 290637/09 Índice Nota Introdutória 7 Diário da Bolívia 11 Comunicados Militares 273 Glossário 295 Nota Introdutória o dia 9 de Outubro de 1967, aos 39 anos de idade, Ernesto NGuevara de la Serna morreu assassinado pelo exército boli‑ viano. Fora capturado dois dias antes, e com ele uma agenda verde, onde registara os acontecimentos e as reflexões sobre a actividade diária da guerrilha, desde havia aproximadamente um ano. O diário foi confiscado pelos militares, mas logo em 1968 foi tornado público, por vias não inteiramente esclarecidas. Falta‑ vam‑lhe no entanto algumas páginas, que os serviços de informa‑ ções bolivianos tinham conseguido manter inacessíveis e que são agora editadas pela primeira vez. Evidentemente, Che foi redigindo estes textos em circuns‑ tâncias extraordinariamente adversas e é de supor que não tivesse a intenção de os publicar, pelo menos não sem antes os submeter a uma revisão. -

Che Guevara's Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy

SOCIALIST VOICE / JUNE 2008 / 1 Contents 249. Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy. John Riddell 250. From Marx to Morales: Indigenous Socialism and the Latin Americanization of Marxism. John Riddell 251. Bolivian President Condemns Europe’s Anti-Migrant Law. Evo Morales 252. Harvest of Injustice: The Oppression of Migrant Workers on Canadian Farms. Adriana Paz 253. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part One. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 254. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part Two. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 255. The Harper ‘Apology’ — Saying ‘Sorry’ with a Forked Tongue. Mike Krebs ——————————————————————————————————— Socialist Voice #249, June 8, 2008 Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy By John Riddell One of the most important developments in Cuban Marxism in recent years has been increased attention to the writings of Ernesto Che Guevara on the economics and politics of the transition to socialism. A milestone in this process was the publication in 2006 by Ocean Press and Cuba’s Centro de Estudios Che Guevara of Apuntes criticos a la economía política [Critical Notes on Political Economy], a collection of Che’s writings from the years 1962 to 1965, many of them previously unpublished. The book includes a lengthy excerpt from a letter to Fidel Castro, entitled “Some Thoughts on the Transition to Socialism.” In it, in extremely condensed comments, Che presented his views on economic development in the Soviet Union.[1] In 1965, the Soviet economy stood at the end of a period of rapid growth that had brought improvements to the still very low living standards of working people. -

Revolutionaries

Relay May/June 2005 39 contexts. In his book Revolutionaries (New York: New Press, 2001), Eric Hobsbawm notes that “all revolutionaries must always believe in the necessity of taking the initia- tive, the refusal to wait upon events to make the revolu- tion for them.” This is what the practical lives of Marx, Lenin, Gramsci, Mao, Fidel tell us. As Hobsbawm elabo- rates: “That is why the test of greatness in revolutionar- ies has always been their capacity to discover the new and unexpected characteristics of revolutionary situations and to adapt their tactics to them.... the revolutionary does not create the waves on which he rides, but balances on them.... sooner or later he must stop riding on the wave and must control its direction and movement.” The life of Che Guevara, and the Latin American insurgency that needs of humanity and for this to occur the individual as part ‘Guevaraism’ became associated with during the ‘years of this social mass must find the political space to express of lead’ of the 1960s to 1970s, also tells us that is not his/her social and cultural subjectivity. For Cuban’s therefore enough to want a revolution, and to pursue it unselfishly El Che was not merely a man of armed militancy, but a thinker and passionately. who had accepted thought, which the reality of what then was The course of the 20th century revolutions and revolu- the golden age of American imperialist hegemony and gave tionary movements and the consolidation of neoliberalism his life to fight against this blunt terrorizing instrument. -

Restructuring the Socialist Economy

CAPITAL AND CLASS IN CUBAN DEVELOPMENT: Restructuring the Socialist Economy Brian Green B.A. Simon Fraser University, 1994 THESISSUBMllTED IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMEW FOR THE DEGREE OF MASER OF ARTS Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies O Brian Green 1996 All rights resewed. This work my not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Siblioth&ye nationale du Canada Azcjuis;lrons and Direction des acquisitions et Bitjibgraphic Sewices Branch des services biblicxpphiques Youi hie Vofrergfereoce Our hie Ncfre rb1Prence The author has granted an L'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive ficence irrevocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant & la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationafe du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, preter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes int6ress6es. The author retains ownership of L'auteur consenre la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial th&se. Ni la thbe ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiefs de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent 6tre imprimes ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisatiow. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Sion Fraser Universi the sight to Iend my thesis, prosect or ex?ended essay (the title o7 which is shown below) to users o2 the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the Zibrary of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

Marxism and Guerrilla Warfare

chapter 6 Marxism and Guerrilla Warfare Marx and Engels had noted the important role played by guerrilla warfare in Spain during the Napoleonic Wars (Marx 1980), in India during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (Marx and Engels 1959), and in the United States, particularly by Confederate forces, during the Civil War (Marx and Engels 1961), but they never made a direct connection between guerrilla warfare and proletarian rev- olution. Indeed, it is notable that Lenin, in writing about guerrilla warfare in the context of the 1905 revolution, made no mention of Marx and Engels in this regard. For Lenin, guerrilla warfare was a matter of tactics relevant “when the mass movement has actually reached the point of an uprising and when fairly large intervals occur between the ‘big engagements’ in the civil war” (Lenin 1972e: 219). Trotsky, as we saw in Chapter 5, thought of guerrilla warfare in the same way, relevant for the conditions of the Civil War but not so for the stand- ing Red Army after the Bolsheviks achieved victory. It was the association between guerrilla warfare and national liberation and anti-imperialist movements over the course of the twentieth century that el- evated guerrilla warfare to the level of strategy for Marxism. There was no one model of guerrilla warfare applied mechanically in every circumstance, but instead a variety of forms reflecting the specific social and historical condi- tions in which these struggles took place. In this chapter I examine the strategy of people’s war associated with Mao Zedong and the strategy of the foco as- sociated with Che Guevara. -

Che and the Return to the Tricontinental

CHE AND THE RETURN TO THE TRICONTINENTAL ROBERT YOUNG1 1 Oxford University. CHE AND THE RETURN TO THE TRICONTINENTAL. 1 1. ‘What we must create is the man of the 21st the end of history. Marx’s legacy was declared century, although this is still a subjective null and void. Yet the active business of aspiration, not yet systematized. This is developing Marx’s legacy in the past fifty years precisely one of the fundamental objectives of had been carried out not in the Soviet Union, our study and work. To the extent that we nor even, I would argue, within much of achieve concrete success on a theoretical European Marxism, but rather in the forms of plane⎯or, vice versa, to the extent that we socialism developed outside the first and draw theoretical conclusions of a broad second worlds, in the course of the anti— character on the basis of our concrete research colonial and anti—imperial struggles in Africa, ⎯we will have made a valuable contribution to Asia and Latin America. Many of these have Marxism—Leninism, to the cause of not survived, shipwrecked on the dangerous humanity’. Che Guevara, ‘Socialism and Man turbulent waters across which every in Cuba’ 1965. decolonised nation has had to navigate. Cuba, 2. How can we think of the legacy of Karl Marx however, is an exception. In 1964 Dean Rusk, today? A legacy involves the act of US Secretary of State, remarked of the new bequeathing, usually in a will or testament. Cuban government ‘we regard that regime as 3 More generally, it is something handed down temporary’. -

North Korea and the Latin American Revolution, 1959-1970

NORTH KOREA AND THE LATIN AMERICAN REVOLUTION, 1959-1970 by MOE (WILLIAM DAVID) TAYLOR B.Sc., The University of Toronto, 2011 M.Sc., Columbia University, 2014 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2020 © Moe (William David) Taylor, 2020 ii The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: North Korea and the Latin American Revolution, 1959-1970 Submitted by Moe (William David) Taylor in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. Examining Committee: Steve H. Lee, History Supervisor Donald L. Baker, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member William French, History Supervisory Committee Member Max Cameron, Political Science University Examiner Glen Peterson, History University Examiner Andre Schmid, East Asian Studies, University of Toronto External Examiner iii Abstract In the 1960s the North Korean leadership embraced the variety of radical Third Worldism associated with Cuba’s Tricontinental Conference of 1966, which advocated a militant, united front strategy to defeat US imperialism via armed struggle across the Global South. This political realignment led to exceptionally intimate political, economic, and cultural cooperation with Cuba and a programme to support armed revolutionary movements throughout Latin America. In the process, North Korea acquired a new degree of prestige with the international left, influencing Cuban and Latin American left-wing discourse on matters of economic development, revolutionary organization and strategy, democracy and leadership. -

De La 'Traición Aprista'

1 De la ‘traición aprista’ al ‘gesto heroico’ Luis de la Puente Uceda y la guerrilla del MIR José Luis Rénique “Bíblicamente parecíamos un pueblo elegido integrado por la gente más sacrificada, tenaz e inteligente, pero con un signo fatal: no llegar a alcanzar la simbólica tierra prometida, bajo la dirección de nuestro Moisés.” Luis Felipe de las Casas1 “No me importa lo que digan los traidores, hemos cerrado el pasado con gruesas lágrimas de acero.” Javier Heraud2 “La entrega es el camino del místico, la lucha es el del hombre trágico; en aquel el final es una disolución, en éste es un choque aniquilador (...) Para la tragedia, la muerte es una realidad siempre inmanente, indisolublemente unida con cada uno de sus acontecimientos.” George Lukács 3 A fines de octubre de 1965 las Fuerzas Armadas del Perú daban cuenta del aniquilamiento --en la zona de Mesa Pelada, parte oriental del departamento del Cuzco-- de la llamada guerrilla Pachacutec. Luis de la Puente Uceda estaba entre las bajas. Sus restos jamás serían encontrados. Caía con él la dirección del movimiento. Barrerían en las semanas siguientes lo que quedaba del alzamiento. Menos de seis meses había tomado suprimir a quienes, “contagiados por el virus del comunismo internacional,” ajenos por ende “al sentimiento de nacionalidad,” habían pretendido obstruir la marcha de la nación “por los caminos del desarrollo.” Conjurado el “peligro rojo” el país podía volver a la vigencia plena de sus instituciones democráticas. Sin olvidar por cierto que se vivía una situación de guerra por el dominio del mundo, distinta que las de antaño, sin fronteras y sin escenarios precisos, con un enemigo ubicuo y multiforme que demandaba estrategias nuevas y una permanente actitud de vigilancia.4 Una mera nota a pie de página de la Guerra Fría latinoamericana. -

Como Ernestito, El Corajudo

Un gigante moral que crece Pág. 5 www.vanguardia.cu Santa Clara, 16 de junio de 2018 Precio: 0.20 ÓRGANO OFICIAL DEL COMITÉ PROVINCIAL DEL PARTIDO EN VILLA CLARA Como Ernestito, el corajudo Pienso en él, en el estereoti- Por Mercedes Rodríguez García Foto: SMB porque el «comandante Gueva- po que pueda formarse por la ra no hacía bandera de ser un reiteración de fotos, anécdotas, corajudo, ni le parecía impor- por las invariables efemérides tante tener el coraje convencio- celebradas casi siempre de nal. Él tenía un coraje austero, la misma forma, en el mismo el de la madre».(2) lugar, a la misma hora. Por ello, está bien expresar Por eso trato de encontrar los con fuerza, fi rmeza y justeza: rasgos primigenios. No aquellos ¡Seremos como el Che! que puedan emanar de sus an- Como el Che hombre, y como cestros, entre los que se cuentan el Che Ernestito. El niño que se —por línea materna— un virrey convertiría en leyenda. Un poco de España y buscadores de oro. genioso, pero un niño solida- Tampoco me interesan los rio, generoso, arriesgado, que del mítico rostro captado un siempre decía lo que pensaba día tremendísimo de duelo, con y nunca dejó de hacer lo que boina, melena, barba y jacket decía. ajustado al cuello, un frío y Un hombre que como padre, nublado octubre «kordasiano», a lo largo de la vida, no pudo que aún recorre el mundo en dedicar mucho tiempo a sus hi- afi ches, pancartas y carteles. jos, pues siempre dio prioridad Este mundo maltrecho, olvida- a las tareas en la dirección del do de afectos y lleno de renco- país que lo adoptó y nacionalizó res.