Che Is Dead, and We All Mourn Him. Why?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Pardos in Vallegrande : an exploration of the role of afromestizos in the foundation of Vallegrande, Santa Cruz, Bolivia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6m01m9bd Author Weaver Olson, Nathan Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pardos in Vallegrande: An Exploration of the Role of Afromestizos in the Foundation of Vallegrande, Santa Cruz, Bolivia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American Studies (History) by Nathan Weaver Olson Committee in Charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Chair Professor Nancy Postero Professor Eric Van Young 2010 Copyright Nathan Weaver Olson, 2010 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Nathan Weaver Olson is approved and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For Kimberly, who lived it. iv EPIGRAPH The descent beckons As the ascent beckoned. Memory is a kind of accomplishment, a sort of renewal even an initiation, since the spaces it opens are new places inhabited by hordes heretofore unrealized … William Carlos Williams v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ………………………………………………………………… iii Dedication …………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph ………………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………... vi List of Charts ………………………………………………………………….. viii List of Maps …………………………………………………………………… ix Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………. x Abstract ………………………………………………………………………… xii Introduction: Viedma and Vallegrande…………………………...……………. 1 Chapter 1: Representations of the Past ………………………………………… 10 Viedma‘s Report ………………………………………………………. 10 Vallegrande Responds …………………………………………………. 18 Pardos and Caballeros Pardos …………………………………………. 23 A Hegemonic Narrative ……………………………………………….. 33 Chapter 2: Vallegrande as Region and Frontier ………………………………. -

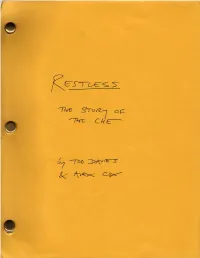

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Che Guevara's Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy

SOCIALIST VOICE / JUNE 2008 / 1 Contents 249. Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy. John Riddell 250. From Marx to Morales: Indigenous Socialism and the Latin Americanization of Marxism. John Riddell 251. Bolivian President Condemns Europe’s Anti-Migrant Law. Evo Morales 252. Harvest of Injustice: The Oppression of Migrant Workers on Canadian Farms. Adriana Paz 253. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part One. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 254. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part Two. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 255. The Harper ‘Apology’ — Saying ‘Sorry’ with a Forked Tongue. Mike Krebs ——————————————————————————————————— Socialist Voice #249, June 8, 2008 Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy By John Riddell One of the most important developments in Cuban Marxism in recent years has been increased attention to the writings of Ernesto Che Guevara on the economics and politics of the transition to socialism. A milestone in this process was the publication in 2006 by Ocean Press and Cuba’s Centro de Estudios Che Guevara of Apuntes criticos a la economía política [Critical Notes on Political Economy], a collection of Che’s writings from the years 1962 to 1965, many of them previously unpublished. The book includes a lengthy excerpt from a letter to Fidel Castro, entitled “Some Thoughts on the Transition to Socialism.” In it, in extremely condensed comments, Che presented his views on economic development in the Soviet Union.[1] In 1965, the Soviet economy stood at the end of a period of rapid growth that had brought improvements to the still very low living standards of working people. -

Che 1Ère Partie: L'argentin 2E Partie: Guerilla

Fiche pédagogique Che 1ère partie: L'Argentin 2e partie: Guerilla Sortie prévue en salles 7 janvier 2009 (1ère partie) 28 janvier 2009 (2ème partie) Film long métrage de fiction, en deux parties, USA/France/ Espagne, 2008 Résumé l'éducation va de pair avec l'indépendance. Les Américains Réalisation : 1ère partie: L'Argentin envoyés en renfort pour soutenir Steven Soderbergh ("Traffic", l'armée cubaine sont impressionnés "Solaris", "Ocean's eleven"…) Comme le sous-titre l'indique, Le par l'organisation des docteur Ernesto Guevara est né en révolutionnaires : dans leur camp, Interprètes : Argentine en 1928. Bien qu'il se soit une école, une infirmerie, un hôpital, Benicio Del Toro (le Che), très jeune impliqué dans différents et même une centrale électrique. Demiàn Bichir (Fidel Castro), mouvements politiques (au Pérou, Toute cette première partie est Rodrigo Santoro (Raùl Castro), en Colombie, en Bolivie ou au rythmée par des extraits en noir et Julia Ormond (Lisa Howard), Guatemala, qu'il traverse à blanc de la visite du Che à New York Catalina Santino Moreno l'occasion de deux voyages latino- en 1964, de la rue (où il est traité (Aleida March), Joachim de américains de plusieurs mois; ce que d'assassin), à l'ONU, où il condamne Almeida (René Barrientos), développait le film "Carnets de l'oppression des peuples latino- Carlos Bardem (Moisés voyage" (2004) de Walter Salles), le américains ("Les 200 millions de Guevara), Marc-André Grondin film ne remonte pas plus tôt que latino-américains qui crèvent de faim (Régis Debray)... 1955. Cette année-là, à Mexico où il se tuent à la tâche pour produire des s'est exilé, Raùl Castro invite son biens pour l'économie des Etats- Scénario et dialogues : ami Guevara, qu'il avait rencontré au Unis") et où il essaie de retourner les Peter Buchman Guatemala, et lui présente son frère, valeurs admises ("Cuba est libre, les Fidel, exilé lui aussi, suite à Etats-Unis sont une prison") : le Production : Steven l'amnistie des prisonniers cubains de représentant des Etats-Unis n'est Soderbergh, Laura Bickford… 1955. -

Revolutionaries

Relay May/June 2005 39 contexts. In his book Revolutionaries (New York: New Press, 2001), Eric Hobsbawm notes that “all revolutionaries must always believe in the necessity of taking the initia- tive, the refusal to wait upon events to make the revolu- tion for them.” This is what the practical lives of Marx, Lenin, Gramsci, Mao, Fidel tell us. As Hobsbawm elabo- rates: “That is why the test of greatness in revolutionar- ies has always been their capacity to discover the new and unexpected characteristics of revolutionary situations and to adapt their tactics to them.... the revolutionary does not create the waves on which he rides, but balances on them.... sooner or later he must stop riding on the wave and must control its direction and movement.” The life of Che Guevara, and the Latin American insurgency that needs of humanity and for this to occur the individual as part ‘Guevaraism’ became associated with during the ‘years of this social mass must find the political space to express of lead’ of the 1960s to 1970s, also tells us that is not his/her social and cultural subjectivity. For Cuban’s therefore enough to want a revolution, and to pursue it unselfishly El Che was not merely a man of armed militancy, but a thinker and passionately. who had accepted thought, which the reality of what then was The course of the 20th century revolutions and revolu- the golden age of American imperialist hegemony and gave tionary movements and the consolidation of neoliberalism his life to fight against this blunt terrorizing instrument. -

Restructuring the Socialist Economy

CAPITAL AND CLASS IN CUBAN DEVELOPMENT: Restructuring the Socialist Economy Brian Green B.A. Simon Fraser University, 1994 THESISSUBMllTED IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMEW FOR THE DEGREE OF MASER OF ARTS Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies O Brian Green 1996 All rights resewed. This work my not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Siblioth&ye nationale du Canada Azcjuis;lrons and Direction des acquisitions et Bitjibgraphic Sewices Branch des services biblicxpphiques Youi hie Vofrergfereoce Our hie Ncfre rb1Prence The author has granted an L'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive ficence irrevocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant & la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationafe du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, preter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes int6ress6es. The author retains ownership of L'auteur consenre la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial th&se. Ni la thbe ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiefs de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent 6tre imprimes ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisatiow. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Sion Fraser Universi the sight to Iend my thesis, prosect or ex?ended essay (the title o7 which is shown below) to users o2 the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the Zibrary of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

De Ernesto, El “Che” Guevara: Cuatro Miradas Biográficas Y Una Novela*

Literatura y Lingüística N° 36 ISSN 0716 - 5811 / pp. 121 - 137 La(s) vida(s) de Ernesto, el “Che” Guevara: cuatro miradas biográficas y una novela* Gilda Waldman M.** Resumen La escritura biográfica, como género, alberga en su interior una gran diversidad de métodos, enfoques, miradas y modelos que comparten un rasgo central: se trata de textos interpre- tativos, pues ningún pasado individual se puede reconstruir fielmente. En este sentido, cabe referirse a algunas de las más importantes biografías existentes sobre el Che Guevara, como La vida en rojo, de Jorge G. Castañeda, (Alfaguara 1997); Che Ernesto Guevara. Una leyenda de nuestro siglo, de Pierre Kalfon (Plaza y Janés, 1997); Che Guevara. Una vida revo- lucionaria, de John Lee Anderson (Anagrama, 2006) y Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che, de Paco Ignacio Taibo II (Planeta, 1996). Por otro lado, en la vida del Che, hay silencios oscuros que las biografías no cubren, salvo de manera muy superficial. Algunos de estos vacíos son retomados por la literatura, por ejemplo, a través de la novela de Abel Posse, Los Cuadernos de Praga. Palabras clave: Che Guevara, biografías, interpretación, literatura. Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s Lives. Four Biographies and one Novel Abstract The biographical writing, as a genre, shelters inside a wide diversity of methods, approaches, points of view and models that share a central trait: it is an interpretative text, since no individual past can be faithfully reconstructed. In this sense, it is worth referring to some of the most diverse and important biographies written about Che Guervara, (Jorge G. Castañeda: La vida en rojo, Alfaguara 1997; Pierre Kalfon: Che Ernesto Guevara. -

Marxism and Guerrilla Warfare

chapter 6 Marxism and Guerrilla Warfare Marx and Engels had noted the important role played by guerrilla warfare in Spain during the Napoleonic Wars (Marx 1980), in India during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (Marx and Engels 1959), and in the United States, particularly by Confederate forces, during the Civil War (Marx and Engels 1961), but they never made a direct connection between guerrilla warfare and proletarian rev- olution. Indeed, it is notable that Lenin, in writing about guerrilla warfare in the context of the 1905 revolution, made no mention of Marx and Engels in this regard. For Lenin, guerrilla warfare was a matter of tactics relevant “when the mass movement has actually reached the point of an uprising and when fairly large intervals occur between the ‘big engagements’ in the civil war” (Lenin 1972e: 219). Trotsky, as we saw in Chapter 5, thought of guerrilla warfare in the same way, relevant for the conditions of the Civil War but not so for the stand- ing Red Army after the Bolsheviks achieved victory. It was the association between guerrilla warfare and national liberation and anti-imperialist movements over the course of the twentieth century that el- evated guerrilla warfare to the level of strategy for Marxism. There was no one model of guerrilla warfare applied mechanically in every circumstance, but instead a variety of forms reflecting the specific social and historical condi- tions in which these struggles took place. In this chapter I examine the strategy of people’s war associated with Mao Zedong and the strategy of the foco as- sociated with Che Guevara. -

Che and the Return to the Tricontinental

CHE AND THE RETURN TO THE TRICONTINENTAL ROBERT YOUNG1 1 Oxford University. CHE AND THE RETURN TO THE TRICONTINENTAL. 1 1. ‘What we must create is the man of the 21st the end of history. Marx’s legacy was declared century, although this is still a subjective null and void. Yet the active business of aspiration, not yet systematized. This is developing Marx’s legacy in the past fifty years precisely one of the fundamental objectives of had been carried out not in the Soviet Union, our study and work. To the extent that we nor even, I would argue, within much of achieve concrete success on a theoretical European Marxism, but rather in the forms of plane⎯or, vice versa, to the extent that we socialism developed outside the first and draw theoretical conclusions of a broad second worlds, in the course of the anti— character on the basis of our concrete research colonial and anti—imperial struggles in Africa, ⎯we will have made a valuable contribution to Asia and Latin America. Many of these have Marxism—Leninism, to the cause of not survived, shipwrecked on the dangerous humanity’. Che Guevara, ‘Socialism and Man turbulent waters across which every in Cuba’ 1965. decolonised nation has had to navigate. Cuba, 2. How can we think of the legacy of Karl Marx however, is an exception. In 1964 Dean Rusk, today? A legacy involves the act of US Secretary of State, remarked of the new bequeathing, usually in a will or testament. Cuban government ‘we regard that regime as 3 More generally, it is something handed down temporary’. -

“Who Is the Macho Who Wants to Kill Me?” Male Homosexuality, Revolutionary Masculinity, and the Brazilian Armed Struggle of the 1960S and 1970S

“Who Is the Macho Who Wants to Kill Me?” Male Homosexuality, Revolutionary Masculinity, and the Brazilian Armed Struggle of the 1960s and 1970s James N. Green In early 1972, Chaim and Mário, members of a small Brazilian revolutionary group, were sentenced to several years in prison for subversive activities.1 Like many other radical left- wing organizations, the group collapsed in the early 1970s during the systematic government campaign to track down and elimi- nate armed resistance to the military regime. While serving time in Tiradentes Prison in São Paulo, Chaim and Mário shared the same cell. Rumors spread among the political prisoners of the different revolutionary organizations held in that prison that the pair was having sex together. “They were immediately isolated, as if they had behaved improperly,” recalled Ivan Seixas some 30 years later. At the time Seixas was also serving a sentence for his involvement in armed struggle. “They were treated as if they were sick,” added Antônio Roberto Espi- nosa, another political inmate and former revolutionary leader imprisoned in the same cellblock during the early 1970s.2 At first, Chaim and Mário denied the rumors of their ongoing affair, but they then decided to admit openly that they were having a relationship and let the other political prisoners confront the news. The unwillingness of the couple to hide their sexual relations provoked an intense discussion among the different groups, which maintained a semblance of discipline, organizational structure, and internal cohesion during their incarceration. To many of the imprisoned guerrilla fighters and other revolutionaries, Chaim and Mário’s bla- I would like to thank Moshe Sluhovsky for his valuable editorial assistance. -

How the CIA Got Che Che Got CIA the How

HOW THE CIA GOT CHE 97 woods cocaine cooker is usually the only thing stirring, the small infantry patrol ran into an enemy ambush. In the tactical manuals that twenty-one-year-old Lieutenant Ruben Amezaga had studied at military academy, enemy fire from any sort of position was rep- resented by neatly dotted arcs. But no such thing ap- peared now. A crack, no louder than a hard ping-pong serve, snapped from high up among the boulders on How the CIA Got Che the steep river gorge, and the patrol guide in front of Lieutenant Amezaga, a local civilian named Epifano Vargas, half-turned in surprise, his arm outfiung. Then came a splatter of short explosions; both the guide and BY ANDREW ST. GEORGE Lieutenant Amezaga were killed before they could ex- change a word. With them died most of the detach- ment's lead section. Six soldiers and the guide were killed, four wounded, fourteen captured by the myste- rious attackers. Even the romantic adventurer's close friends seldom knew where he was or what he was Eight soldiers got away. With terror-marbled eyes, doing after he left Cuba. America's Central they ran cross-jungle several miles until they dared Intelligence Agency didn't always have an open form up again under a senior sergeant. Then they line to Che Guevara. But as an apparatus fre- loped on until they hit a narrow dirt road, where a quently given to chasing shadows, the CIA petroleum truck picked them up and took them to knew precisely where he was and how to help Camiri, headquarters base of the Bolivian Fourth In- run him down at the very end.