Managing Biosecurity Across Borders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCHAPPER, Antoinette and Emilie WELLFELT. 2018. 'Reconstructing

Reconstructing contact between Alor and Timor: Evidence from language and beyond a b Antoinette SCHAPPER and Emilie WELLFELT LACITO-CNRSa, University of Colognea, and Stockholm Universityb Despite being separated by a short sea-crossing, the neighbouring islands of Alor and Timor in south-eastern Wallacea have to date been treated as separate units of linguistic analysis and possible linguistic influence between them is yet to be investigated. Historical sources and oral traditions bear witness to the fact that the communities from both islands have been engaged with one another for a long time. This paper brings together evidence of various types including song, place names and lexemes to present the first account of the interactions between Timor and Alor. We show that the groups of southern and eastern Alor have had long-standing connections with those of north-central Timor, whose importance has generally been overlooked by historical and linguistic studies. 1. Introduction1 Alor and Timor are situated at the south-eastern corner of Wallacea in today’s Indonesia. Alor is a small mountainous island lying just 60 kilometres to the north of the equally mountainous but much larger island of Timor. Both Alor and Timor are home to a mix of over 50 distinct Papuan and Austronesian language-speaking peoples. The Papuan languages belong to the Timor-Alor-Pantar (TAP) family (Schapper et al. 2014). Austronesian languages have been spoken alongside the TAP languages for millennia, following the expansion of speakers of the Austronesian languages out of Taiwan some 3,000 years ago (Blust 1995). The long history of speakers of Austronesian and Papuan languages in the Timor region is a topic in need of systematic research. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

Consonant Insertions: a Synchronic and Diachronic Account of Amfo'an

Consonant Insertions: A synchronic and diachronic account of Amfo'an Kirsten Culhane A thesis submitted for the degree of Bachelor ofArts with Honours in Language Studies The Australian National University November 2018 This thesis represents an original piece of work, and does not contain, inpart or in full, the published work of any other individual, except where acknowl- edged. Kirsten Culhane November 2018 Abstract This thesis is a study of synchronic consonant insertions' inAmfo an, a variety of Meto (Austronesian) spoken in Western Timor. Amfo'an attests synchronic conso- nant insertion in two environments: before vowel-initial enclitics and to mark the right edge of the noun phrase. This constitutes two synchronic processes; the first is a process of epenthesis, while the second is a phonologically conditioned affixation process. Which consonant is inserted is determined by the preceding vowel: /ʤ/ occurs after /i/, /l/ after /e/ and /ɡw/ after /o/ and /u/. However, there isnoregular process of insertion after /a/ final words. This thesis provides a detailed analysis of the form, functions and distribution of consonant insertion in Amfo'an and accounts for the lack of synchronic consonant insertion after /a/-final words. Although these processes can be accounted forsyn- chronically, a diachronic account is also necessary in order to fully account for why /ʤ/, /l/ and /ɡw/ are regularly inserted in Amfo'an. This account demonstrates that although consonant insertion in Amfo'an is an unusual synchronic process, it is a result of regular sound changes. This thesis also examines the theoretical and typological implications 'of theAmfo an data, demonstrating that Amfo'an does not fit in to the categories previously used to classify consonant/zero alternations. -

'Undergoer Voice in Borneo: Penan, Punan, Kenyah and Kayan

Undergoer Voice in Borneo Penan, Punan, Kenyah and Kayan languages Antonia SORIENTE University of Naples “L’Orientale” Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology-Jakarta This paper describes the morphosyntactic characteristics of a few languages in Borneo, which belong to the North Borneo phylum. It is a typological sketch of how these languages express undergoer voice. It is based on data from Penan Benalui, Punan Tubu’, Punan Malinau in East Kalimantan Province, and from two Kenyah languages as well as secondary source data from Kayanic languages in East Kalimantan and in Sawarak (Malaysia). Another aim of this paper is to explore how the morphosyntactic features of North Borneo languages might shed light on the linguistic subgrouping of Borneo’s heterogeneous hunter-gatherer groups, broadly referred to as ‘Penan’ in Sarawak and ‘Punan’ in Kalimantan. 1. The North Borneo languages The island of Borneo is home to a great variety of languages and language groups. One of the main groups is the North Borneo phylum that is part of a still larger Greater North Borneo (GNB) subgroup (Blust 2010) that includes all languages of Borneo except the Barito languages of southeast Kalimantan (and Malagasy) (see Table 1). According to Blust (2010), this subgroup includes, in addition to Bornean languages, various languages outside Borneo, namely, Malayo-Chamic, Moken, Rejang, and Sundanese. The languages of this study belong to different subgroups within the North Borneo phylum. They include the North Sarawakan subgroup with (1) languages that are spoken by hunter-gatherers (Penan Benalui (a Western Penan dialect), Punan Tubu’, and Punan Malinau), and (2) languages that are spoken by agriculturalists, that is Òma Lóngh and Lebu’ Kulit Kenyah (belonging respectively to the Upper Pujungan and Wahau Kenyah subgroups in Ethnologue 2009) as well as the Kayan languages Uma’ Pu (Baram Kayan), Busang, Hwang Tring and Long Gleaat (Kayan Bahau). -

A PDF Combined with Pdfmergex

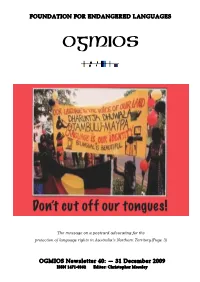

!"#$%&'("$)!"*)+$%&$,+*+%)-&$,#&,+.) ) OGMIOS The message on a postcard advocating for the protection of language rights in Australia’s Northern Territory (Page 3) ",/(".)$012304405)678)9):;)%0<0=>05)?77@) (..$);6A;B7:C?))))))+DE4F58)GH5E24FIH05)/F2030J) 2 DEBFD<'C4G"64$$4+'HI,'J'KL'=4/4M14+'NIIO' F<<C'LHPLQIKRN''''''()#$*+,'07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;' !""#"$%&$'()#$*+,'!)+#%&*'-+."/*$$' 0*&$+#1.$#&2'()#$*+",'3*24+'564&/78'9*"4:7'56;$748'<4+4&%'=>!2*"$#&*8'07+#"$*:74+'?%)@#46)8'A+%&/#"'B'?.6$8'' C#/7*6%"'D"$64+8'!&)+4%'3#$$4+' ' !"#$%&$'$()'*+,$"-'%$.' /012,3()+'14.' ' 07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;8' A*.&)%$#*&'@*+'(&)%&24+4)'X%&2.%24"8' O'S4"$)4&4'0+4"/4&$8' LPN'5%#61+**Y'X%&48'' 0%T4+"7%M'?4#27$"8' 5%$7'5!L'P!!8'(&26%&)' 34%)#&2'3EH'P?=8'(&26%&)' &*"$64+V/7#1/7%W)4M*&W/*W.Y'' /7+#"M*"464;UIV;%7**W/*M'' 'GGGW*2M#*"W*+2' The Austronesian Languages......................................... 19! LW'()#$*+#%6 3! Immersion – a film on endangered languages ............... 19! Cover Story: Northern Territory’s small languages sidelined from schools ...................................................... 3! RW'\6%/4"'$*'2*'*&'$74'S41 20! NW! =4T46*:M4&$'*@'$74'A*.&)%$#*& 4! Irish upside down............................................................ 20! Resolution of the FEL XIII Conference, Khorog, Tajikistan, OW'A*+$7/*M#&2'4T4&$" 21! 26, September, 2009 ........................................................ 4! HRELP Workshop: Endangered Languages, endangered FEL and UNESCO Atlas partnership................................ 4! knowledge & sustainability............................................. -

WILC Vol9 Mcallister Optimized.Pdf

WORKPAPBRS IN INDONBSIAN LANGUAGBS.... AND CULTURBS VOLUMS 9 - IRIAN JAYA • . -' , ~ .. • Cenderawasih University ~ and The Summer InstLtute of Linguistics in cooperation with The Department of Education and Culture WORKPAPBRS IN INDONESIAN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES VOLUME 9 - IRIAN JAYA Margaret Hartzler, LaLani Wood, Editors Cenderaw8sih University and The Summer Institute of Linguistics in cooperation with The Department of Education and Cultu-re J Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures Volume 9 - Irian Jaya Margaret Hartzler, LaLani Wood, Editors Printed 1991 Jayapura, Irian Jaya, Indonesia copies of this publication may be obtained from Summer Institute of Linguistics P.O. Box 1800 Jayapura, Irian Jaya 99018 Indonesia Microfiche copies of this and other pUblications of the Summer Institute of Linguistics may be obtained from . Academic Book Center Summer Institute of Linguistics 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236 U.S.A. ISBN 979-8132-734 Prakata Saya menyambut dengan gembira penerbitan buku Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures , Volume 9 - Irian Jaya. Penerbitan ini merupakan bukti kemajuan serta keberhasilan yang dicapai oleh Proyek Kerjasama Universitas Cenderawasih dengan Summer Institute of Linguistics , Irian Jaya. Buku ini juga merupakan wujud nyata peranserta para anggota SIL dalam membantu pengembangan masyarakat umumnya dan masyarakat pedesaan Irian Jaya khususnya. Selain berbagai informasi ilmiah tentang bahasa-bahasa daerah dan kebudayaan suku-suku setempat, buku ini sekaligus mengungkapkan sebagian kecil kekayaan budaya bangs a kita yang berada di Irian Jaya. Dengan adanya penerbitan ini, diharapkan penulis-penulis yang lain akan didorong minatnya agar dapat menyumbangkan pengetahuan yang berguna bagi generasi-generasi yang akan datang dan untuk kepentingan pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan. -

South Sulawesi Pronominal Clitics: Form, Function and Position

Studies in Philippine Languages and Cultures Volume 17 (2008), 13–65 South Sulawesi pronominal clitics: form, function and position Daniel Kaufman Cornell University The present article ofers the most comprehensive overview to date of pronominal clitic syntax in the South Sulawesi (SSul) family (Malayo- Polynesian, Austronesian). The fundamental aspects of SSul morphosyntax are explained with special attention given to case and agreement phenomena. The SSul system is then compared to Philippine-type languages, which are known to be more morphosyntactically conservative, and thus may represent the type of system from which Proto-SSul descended. A full array of syntactic environments are investigated in relation to clitic placement and the results are summarized in the conclusion. The positioning properties of the set A pronouns are of particular interest in that they are similar to Philippine clitics in being second-position elements but dissimilar to them in respecting the contiguity of a potentially large verbal constituent, often resulting in placement several words away from the left edge of their domain. Finally, notes on the form of modern SSul pronoun sets and the reconstruction of Proto-SSul pronouns are presented in the appendix. 1. Background The languages of the South Sulawesi (henceforth SSul) family are spoken on the southwestern peninsula of Sulawesi. Selayar island marks the southern boundary of the SSul area, while the northern boundary is marked by Mamuju on Sulawesi’s west coast, the Sa’dan area further inland, and the environs of Luwuk on the northeastern edge. Outside of Sulawesi, the Tamanic languages of western Kalimantan have been identiied 1 as outliers of the SSul family. -

Mian Grammar

A Grammar of Mian, a Papuan Language of New Guinea Olcher Sebastian Fedden Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper 2 To my parents 3 Abstract This thesis is a descriptive grammar of the Mian language of Papua New Guinea. The corpus data on the basis of which I analyzed the structures of the language and their functions was obtained during nine months of field work in Yapsiei and Mianmin, Telefomin District, Sandaun Province, Papua New Guinea. The areas of grammar I cover in this thesis are phonology (ch. 2), word classes (ch. 3), nominal classification (ch. 4 and 5), noun phrase structure (ch. 6), verb morphology (ch. 7), argument structure and syntax of the clause (ch. 8), serial verb constructions and clause chaining (ch. 9), operator scope (ch. 10), and embedding (ch. 11). Mian has a relatively small segmental phoneme inventory. The tonal phonology is complex. Mian is a word tone language, i.e. the domain for assignment of one of five tonemes is the phonological word and not the syllable. There is hardly any nominal morphology. If a noun is used referentially, it is followed by a cliticized article. Mian has four genders. Agreement targets are the article, determiners, such as demonstratives, and the pronominal affixes on the verb. The structure of the NP is relatively simple and constituent order is fixed. The rightmost position in the NP is reserved for a determiner; e.g. -

Appositive Possession in Ainu and Around the Pacific

Appositive possession in Ainu and around the Pacific Anna Bugaeva1,2, Johanna Nichols3,4,5, and Balthasar Bickel6 1 Tokyo University of Science, 2 National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, Tokyo, 3 University of California, Berkeley, 4 University of Helsinki, 5 Higher School of Economics, Moscow, 6 University of Zü rich Abstract: Some languages around the Pacific have multiple possessive classes of alienable constructions using appositive nouns or classifiers. This pattern differs from the most common kind of alienable/inalienable distinction, which involves marking, usually affixal, on the possessum and has only one class of alienables. The language isolate Ainu has possessive marking that is reminiscent of the Circum-Pacific pattern. It is distinctive, however, in that the possessor is coded not as a dependent in an NP but as an argument in a finite clause, and the appositive word is a verb. This paper gives a first comprehensive, typologically grounded description of Ainu possession and reconstructs the pattern that must have been standard when Ainu was still the daily language of a large speech community; Ainu then had multiple alienable class constructions. We report a cross-linguistic survey expanding previous coverage of the appositive type and show how Ainu fits in. We split alienable/inalienable into two different phenomena: argument structure (with types based on possessibility: optionally possessible, obligatorily possessed, and non-possessible) and valence (alienable, inalienable classes). Valence-changing operations are derived alienability and derived inalienability. Our survey classifies the possessive systems of languages in these terms. Keywords: Pacific Rim, Circum-Pacific, Ainu, possessive, appositive, classifier Correspondence: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 1. -

Comparative Vernacural Word Lists from North Coast of Irian Jaya Indonesia, 1973()

J * .U'. _J T >f T _ t W W ^ (j ‘"* ' . ff I UNIVERSIT AS INDONESIA ^ FAKULTAS SASTRA -J PERPUSTAKAAN *' I R W Z i € 3 0 J / ' ; * f a Jf{(h t-fg* U COMPARATIVE VERNACULAR WORD LISTS froia the north coast area of IRIAN JAYA, INDONESIA Tho following languages are listed: Indonesian Serui Metawedya Isirawa Sobei Kwesten ICwopke Berik ¥akde Kasimasi Keder Beneraf Betaf Yamna Kapitiauv; English The languages were recorded by members of the SUMMER INSTITUTE OP LINGUISTICS working in cooperation with UNIVBRSITAS CENDERAWASIH May, 1973 SERUI Jap on Island is locatcd between Biak Island and the north, coast of Irian Jaya. Serui Language is spoken on the southeast coast of Japen and on the islands off that coast, lhere may bo 9000 speakers of the various dialects' Of Se^tii^' Serui Language data was given by Max Wondiwoy and recorded by Joyce Sterner in December, 1972 at Jayapura, Irian Jayia* KETAWEDYA Metawedya Language is spoken on the north coast of Irian Jaya in the Apawar-Tor River areas, but the exact location and number of speakers is unknown. Mc-tawedya Language Sata was given by Betrus and recorded by James Dean in August, 1972 at Kwekwet. ISIRAWA Isirawa Language is spoken on the north ocast of Irian Jaya. Its villages extend west from Sarmi almost as far as the Apawar River. There may be 1600 speakers of Isirawa. Isirawa Language data was given h y Sebnot Scyamor and recorded by Robert Sterner in March, 1973 at Mararena village just east of Sarmi. SQB3I Sobei Language is spoken on the north coast in Sarmi, _ Bagaiserwar, and Sawar.