An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari

The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari Tanja M. Männel & Peter Breunig Abstract Résumé Since their discovery in the mid-20th century, the terracottas Depuis leur découverte au milieu du XXe siècle, les sculptures of the Nok Culture in Central Nigeria, which represent the de la culture Nok au Nigeria central sont connues, au-delà des earliest large-scale sculptural tradition in Sub-Saharan Af- spécialistes, comme la tradition la plus ancienne des sculptures rica, have attracted attention well beyond specialist circles. de grande taille de l’Afrique subsaharienne. Toutefois leur Their cultural context, however, remained virtually unknown contexte culturel resta inconnu pour longtemps, dû à l’absence due to the lack of scientifically recorded, meaningful find de situations de fouille pertinentes démontrées scientifiquement. conditions. Here we will describe an archaeological feature Ici nous décrivons une découverte, trouvée à Pangwari, lieu uncovered at the almost completely excavated Nok site of de découverte Nok, située dans le sud de l’état de Kaduna, qui Pangwari, a settlement site located in the South of Kaduna fourni des informations suffisantes montrant que des sculptures State, which provided sufficient information to conclude that en terre cuite ont été détruites délibérément et puis déposées, ce the terracotta sculptures had been deliberately destroyed qui, par conséquent, met en évidence exemplaire l’aspect rituel and then deposited, emphasising the ritual aspect of early de l’ancien art plastique africain. Auparavant, des observations African figurative art. similaires ont été faites sur d’autres sites de recherches. Similar observations were made at various other sites Or les sculptures en terre cuite découvertes à Pangwari we had examined previously. -

Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp

NYAME AKUMA No. 73 June 2010 NIGERIA in the production of abundant and beautiful clay figu- rines. Its enigmatic character was underlined by the Outline of a New Research Project lack of any known precursor or successors leaving on the Nok Culture of Central the Nok Culture as a flourishing but totally isolated Nigeria, West Africa phenomenon in the archaeological sequence of the region. Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp Another surprise was the discovery of iron- smelting furnaces in Nok contexts, and at that time Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp amongst the earliest evidence of metallurgy in sub- Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main Saharan Africa (Fagg 1968; Tylecote 1975). The com- Institut für Archäologische bination of early iron and elaborated art – in our west- Wissenschaften ern understanding – demonstrated the potential of Grüneburgplatz 1 the Nok Culture with regard to metallurgical origins 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany and the emergence of complex societies. emails: [email protected], [email protected] However, no one continued with the work of Bernard Fagg. Instead of scientific exploration, the Nok Culture became a victim of illegal diggings and internationally operating art dealers. The result was Introduction the systematic destruction of numerous sites and an immense loss for science. Most Africanist archae- Textbooks on African archaeology and Afri- ologists are confronted with damage caused by un- can art consider the so-called Nok Culture of central authorized diggings for prehistoric art, but it appears Nigeria for its early sophisticated anthropomorphic as if Nok was hit the hardest. Based on the extent of and zoomorphic terracotta figurines (Figures 1 and damage at numerous sites that we have seen in Ni- 2), and usually they emphasize the absence of con- geria, and according to the reports of those who had textual information and thus their social and cultural been involved in the damage, many hundreds if not purpose (Garlake 2002; Phillipson 2005; Willett 2002). -

Nok Terra-Cotta Discourse

IJournals: International Journal of Social Relevance & Concern ISSN-2347-9698 Volume 4 Issue 9 September 2016 NOK TERRA-COTTA DISCOURSE: PERSPECTIVES OF THE CERAMIST AND THE SCULPTOR Henry Asante (MFA, Ph.D) SCULPTURE UNIT DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS AND DESIGN, UNIVERSITY OF PORT HAROCURT, PORT HAROCOURT, NIGERIA. [email protected] +2348056056977(08056056977) AND PETERS, EDEM E. (MFA, M. Ed, Ph.D) CERAMICS UNIT DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS AND DESIGN, UNIVERSITY OF PORT HARCOURT, PORT HARCOURT, NIGERIA. [email protected] [email protected] +2348023882338(08023882338) ABSTRACT This article recalls the memory of one of the most remarkable art traditions on the African continent that survived many years of practice in a material and technique which hitherto could have been attributed to sculpture but has lately attracted controversial argument between sculpture and ceramics over the area of production it belongs. The Nok terra-cotta art works comprised human and animal forms and were made by a people that existed in an area near the confluence of Niger and Benue Rivers in central Nigeria between 500 BC and 200 AD. These hundreds of existed art works are at the center of an intellectual discourse, seeking an answer to the question as to who made the art works, the sculptor or the ceramist. Evidence from scholars, availability of clay as material, production techniques and end use or the possibility of the figures been used as ritual objects are among the parameters used in the attempt to establish the actual area of production the figures situate. Key words: Nok, terra-cotta, sculpture, ceramics, production Introduction The ownership of the Nok terra Cotta head has become a controversial issue between ceramics and sculpture. -

9781107064607 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06460-7 — The Yoruba from Prehistory to the Present Aribidesi Usman , Toyin Falola Index More Information 491 Index abà 45 Apa I 38 Abdulsalam Abubakar 390 Apala 315 àbíkú 278 Ara War 75 Abinu 17 archaeological evidence 4 , 19 , 41 , 51 , abolition laws 214 52 , 59 , 61 , 74 , 266 aboriginal 108 Ilare 96 abulé 46 , see also village Olle 112 aceramic phase 32 Owu 92 Action Group 362 Oyo- Ile 81 activism, women 341 , 356 Archaic Period 43 Adegoke Adelabu 353 architecture, slaves 233 , 238 Ade Obayemi 38 , 103 ar ẹ m ọ 121 Adósùu Sango 304 Are- Ona- Kakanfo 120 , 151 , 153 , 221 Afonja 151 , 161 , 221 , 431 , 432 àtíbàbà 46 Africanism 229 Atlantic trade 141 , 150 , 205 , 206 , agannigan 157 208 , 215 àgbà egungun 281 disrupted 144 Agbekoya Rebellion 372 authority 121 Agbonmiregun 1 extension 217 Agonnigon 111 autochthonous 4 , 103 , 109 agriculture 40 , 243 – 247 , 417 Awole 151 , 161 Aguda 238 ahéré 47 Babalawo 219 , 231 , 275 , 291 , 294 , Ahmed Baba 4 299 , 300 Ajaka 93 Badagry 38 Aja kingdom 14 Bariba 14 , 16 ajele 123 , 130 , 153 , 200 Basorun Gaha 151 , 221 , 431 Ajasepo 104 Bayarabe 4 Ajibod ẹ 33 beads 75 , 124 , 266 , 310 , see also Ajibosin 88 glass beads Aku 5 , 235 Benin 1 , 53 , 74 , 141 , 143 , 295 , 298 Akure 25 , 224 Ilorin 266 Alaai n Ajagbo 118 Biafra 369 Aladura churches 425 , 426 Bight of Benin 4 , 75 , 141, 146 , Alale (ruler of Idasin) 3 207 , 211 All Progressive Congress (APC) 399 boundary markers 46 Al- Salih 221 brass and bronze sculptures 63 , 67 , 298 ancestors 280 Brazil 207 -

Ife–Sungbo Archaeological Project: Aims and Objectives

DIRECTORS: IFE –SUNGBO GÉRARD L. CHOUIN, PHD Rapport ADISA B. OGUNFOLAKAN, PHD Introduction generale ARCHAEOLOGICAL A.1 Collaborations / mobilization des moyens Collaborateurs universitaires: MAIN ACADEMIC PARTNERS Etudians PROJECT Institutions PRELIMINARY REPORT ON Financiers EXCAVATIONS AT ITA YEMOO, ILE-IFE, OSUN STATE AND ON RAPID A.2 Urbanisation / la problematique des enceintes pour la chronologie de l’urbanisation en SSESSMENT OF ARTHWORK ITES AT Afrique forestiereA E S EREDO AND ILARA-EPE, LAGOS STATE A.3 L’archeologie d’Ile-Ife JUNE–JULY 2015 A.4 Ita Yemoo: fouilles par Willett, 1957 B. Recherches en Archives Papers of Professor Frank Willett, 1925-2006, Anthropologist, Archaeologist, Professor and Director of the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, 1976-1990 C. Recherches archeologiques C.1. Pavements MAIN FUNDING AGENCY C.2. Enceinte: interpretation stratigraphique, reprise des travaux de Willett, datation C.3. Travail preparatoire a Sungbo’s Eredo: visite, prise de contacts et premier releve D. Analyses en cours D.1 Sedimentologie (Alain Person) D.2 Radiocarbon dating (Beta Analytics) D.3 Glass / material culture analysis OTHER SPONSORS AND PARTNERS 1 Table of Contents Executive summary ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 A. Partnerships and funding ......................................................................................................................... -

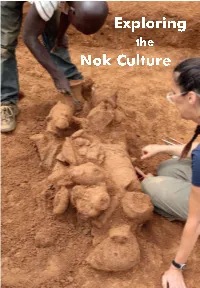

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture Joint Research Project of Goethe University Frankfurt/Main, Germany & National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria A publication of Goethe University, Institute for Archaeological Sciences, African Archaeology and Archaeobotany, Frankfurt/Main, Germany January 2017 Text by Peter Breunig Editing by Gabriele Franke & Annika Schmidt Translation by Peter Dahm Robertson Layout by Kirstin Brauneis-Fröhlich Cover Design by Gabriele Försterling Drawings by Monika Heckner & Barbara Voss Maps by Eyub F. Eyub Photos by Frankfurt Nok Project, Goethe University Printed by Goethe University Computer Center © 2017 Peter Breunig, Goethe University Project Funding Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) Partners Support A Successful Collaboration The NCMM and Goethe University continued their successful collaboration for field research on the Nok Culture Anyone interested in West Africa’s – and in central Nigeria. Starting in 2005, particularly Nigeria’s – prehistory will NCMM has ever since taken care of eventually hear about the Nok Culture. Its administrative matters and arranged artful burnt-clay (terracotta) sculptures the participation of their archaeological make it one of Africa’s best known experts which became valuable members ancient cultures. The Nok sculptures are of the project’s team. More recently, among the oldest in sub-Saharan Africa archaeologists from Ahmadu Bello and represent the origins of the West University in Zaria and Jos University African tradition of portraying people and joined the team. Together, the Nigerian animals. This brochure is a summary of and German archaeologists completed what we know about the Nok Culture and difficult work to gain information on this how we know what we know. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Trabajo Fin De Grado

Trabajo Fin de Grado Título del trabajo: Las terracotas de la cultura Nok de Nigeria English tittle: The Nigeria Nok culture terracottas Autor Federico Beltrán Moreno Director/es José Luis Pano Gracia FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS Año 2017 ÍNDICE RESUMEN…………………………………………………………………………….Pág. 3 1. INTRODUCCIÓN 1.1. JUSTIFICACIÓN DEL TEMA…………………………………………...Pág. 3 1.2. ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN……………………………………………Pág. 4 1.3. METODOLOGÍA APLICADA…………………………………………...Pág. 6 1.4. OBJETIVOS……………………………………………………………….Pág. 7 2. LAS TERRACOTAS DE LA CULTURA NOK 2.1. EL NACIMIENTO DE LA ESCULTURA NEGROAFRICANA……......Pág. 7 2.2. EL DESCUBRIMIENTO DEL ARTE NOK……………………………..Pág. 10 2.3. CRONOLOGIAS DEL ARTE NOK……………………………………...Pág. 13 2.4. CARACTERÍSTICAS FORMALES DE LAS TERRACOTAS……….....Pág. 14 2.5. FUNCIÓN Y USO DE LAS PIEZAS……………………………………..Pág. 18 2.6. VARIEDAD DE ESTILOS ESCULTÓRICOS EN NIGERIA……………Pág. 20 2.7. LA PRESENCIA DE LAS TERRACOTAS NOK EN ESPAÑA. LA FUNDACIÓN JIMÉNEZ-ARELLANO ALONSO………………………..Pág. 23 3. CONCLUSIONES…………………………………………………………………...Pág. 25 4. BIBLIOGRAFÍA……………………………………………………………………..Pág. 27 5. ILUSTRACIONES.…………………………………………………………………..Pág. 29 6. APÉNDICE DE OBRAS……………………………………………………………..Pág. 46 2 RESUMEN En este trabajo de fin de grado se ofrece una visión global sobre lo más importante que conocemos hasta el momento presente acerca de la cultura Nok del norte de Nigeria. Repasaremos desde los inicios de su descubrimiento, pasando luego por los yacimientos más importantes de la misma, y finalmente hablaremos tanto de las características formales de las propias terracotas como de la variedad de las mismas. Tras ello, y partir de las teorías más relevantes, realizaremos una síntesis sobre el posible uso y significado de estas piezas. 1. -

Illicit Traffic in Cultural Property in Nigeria: Aftermaths and Title Antidotes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Illicit Traffic in Cultural Property in Nigeria: Aftermaths and Title Antidotes Author(s) AKINADE, Olalekan Ajao AKINADE Citation African Study Monographs (1999), 20(2): 99-107 Issue Date 1999-06 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68183 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 20-2/2 03.4.3 9:49 AM ページ99 African Study Monographs, 20(2): 99-107, June 1999 99 ILLICIT TRAFFIC IN CULTURAL PROPERTY IN NIGERIA: AFTERMATHS AND ANTIDOTES Olalekan Ajao AKINADE National Museum, Nigeria ABSTRACT The concepts of national cultures and African cultures generated heated debate when scholarship was at its low ebb, thus promoting some scholars to argue against the existence of African culture. Today African reigns supreme in the art world, both ancient and contemporary, a result of the manifestations of the rich culture of Africa as a whole. In Nigeria, research and museum activities have exposed two thousand years of ancient art works of Nigeria, among other aspects of the rich cultures of the country. The ancient art works of Nigeria and her archaeological heritage have generated interest as well as interna- tional recognition. The rampant loss, theft, and pillage of cultural property in Nigeria is the central focus of this article. It looks at the immediate and remote causes of illicit traffic in cultural property. The article identifies some of the aftermaths of the nefarious activities, and proffers some solutions that may check them. Key Words: Illicit; Museum; Heritage; Nefarious; Traffic; Solutions. -

The Relationship Between the Later Stone Age and Iron Age Cultures of Central Tanzania

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE LATER STONE AGE AND IRON AGE CULTURES OF CENTRAL TANZANIA Emanuel Thomas Kessy B.A. University of Dar es Salaam, 1991 M.Phi1. Cambridge University, 1992 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Emanuel Thomas Kessy, 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSlTY Spring 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Emanuel Thomas Kessy DEGREE: TITLE OF THESIS: The Relationship Between the Later Stone Age (LSA) and Iron Age (IA) Cultures of Central Tanzania EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chair: Dongya Yang Assistant Professor Cathy D'Andre;, Associate Professor Senior Supervisor David Burley, Professor Diane Lyons, Assistant Professor University of Calgary Ross Jamieson, Assistant Professor Internal Examiner Adria LaViolette, Associate Professor University of Virginia External Examiner Date Approved: SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project nr extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, acd to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

World Bank Document

Environmentally Sustainable AFTESWORKING PAPER DevelopmentDivision v- EnvironmentalAssessment Working Paper No.4 Public Disclosure Authorized CULTURAL PROPERTY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENTS IN Public Disclosure Authorized SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA A Handbook Public Disclosure Authorized by June Taboroff and Cynthia C. Cook September 1993 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmentally Sustainable Development Division Africa Technical Department The World Bank EnvironmentalAssessment Working Paper No. 4 Cultural Property and Environmental Assessments in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Handbook by June Taboroff and Cynthia C. Cook September1993 EnvironmentallySustainable Development Division SocialPolicy and Resettlement Division TechnicalDepartment EnvironmentDepartment AfricaRegion TheWorld Bank Thispaper has been prepared for internal use. The views and interpretabonsarethose of the authors and should not be attri- butedto the World Bank, to itsaffiliated organizations, orto any individualacting on their behalf. PREFACE The use of environmentalassessment (EA) to identifythe environmentalconsequences of developmentprojects and to take these consequencesinto account in project design is one of the World Bank's most important tools for ensuring that developmentstrategies are environmentally sound and sustainable. The protectionof cultural heritage - sites, structures, artifacts, and remains of archaeological,historical, religious, cultural, or aesthetic value - is one importantobjective of the EA process. The Bank's EA procedures require its Borrowersto undertakecultural -

Nok Early Iron Production in Central Nigeria – New Finds and Features

Nok Early Iron Production in Central Nigeria – New Finds and Features Henrik Junius Abstract Résumé Between 2005 and 2013, new archaeometallurgical Entre 2005 et 2013, plusieurs campagnes de fouilles finds and features in central Nigeria resulted from conduites dans le cadre du projet de recherche Nok, de several excavation campaigns conducted by the l‘Université Goethe de Francfort, ont livré de nouvelles Nok research project, Goethe University, Frankfurt. découvertes et apporté de nouvelles caractéristiques pour This article presents the first excavation results and la paléo-métallurgie au Nigeria central. Cet article présente compares the newly generated data to the publications les premiers résultats de fouille et compare les données on the Nok iron smelting site of Taruga from 40 years nouvellement acquises aux données publiées du site Nok ago. All newly excavated sites find close resemblance de métallurgie du fer de Taruga il y a 40 ans. Tous les sites in each other in regards to dates in the middle of the récemment fouillés présentent de fortes similitudes en ce qui first millennium BCE, furnace design, find distribution concerne leurs dates, situées à la moitié du premier millénaire and find properties. In some cases, the finds from the avant notre ère, la conception du four, la distribution et les Taruga valley fit in the new and homogeneous picture of caractéristiques des découvertes. Dans quelques cas, les Nok iron metallurgy. However, Taruga differs from the vestiges de la vallée Taruga s’inscrivent dans cette nouvelle new sites in its variety of furnace design and number image homogène de la sidérurgie Nok.