The Role of Art Objects in Technological Development of Nigeria: an Archaeological Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: the Igbo Experience

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: The Igbo Experience A thesis submitted to the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS), Universität Bayreuth, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Dr. Phil.) in English Linguistics By Uchenna Oyali Supervisor: PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe Mentor: Prof. Dr. Susanne Mühleisen Mentor: Prof. Dr. Eva Spies September 2018 i Dedication To Mma Ụsọ m Okwufie nwa eze… who made the journey easier and gave me the best gift ever and Dikeọgụ Egbe a na-agba anyanwụ who fought against every odd to stay with me and always gives me those smiles that make life more beautiful i Acknowledgements Otu onye adịghị azụ nwa. So say my Igbo people. One person does not raise a child. The same goes for this study. I owe its success to many beautiful hearts I met before and during the period of my studies. I was able to embark on and complete this project because of them. Whatever shortcomings in the study, though, remain mine. I appreciate my uncle and lecturer, Chief Pius Enebeli Opene, who put in my head the idea of joining the academia. Though he did not live to see me complete this program, I want him to know that his son completed the program successfully, and that his encouraging words still guide and motivate me as I strive for greater heights. Words fail me to adequately express my gratitude to my supervisor, PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe. His encouragements and confidence in me made me believe in myself again, for I was at the verge of giving up. -

Encoded Language As Powerful Tool. Insights from Okǝti Ụmụakpo-Lejja Ọmaba Chant

Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 2020, 8(3) ISSN 1339-4584 DOI: 10.2478/jolace-2020-0025 Traditional Segregation: Encoded Language as Powerful Tool. Insights from Okǝti Ụmụakpo-Lejja Ọmaba chant Uchechukwu E. Madu Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Nigeria [email protected] Abstract Language becomes a tool for power and segregation when it functions as a social divider among individuals. Language creates a division between the educated and uneducated, an indigene and non-indigene of a place; an initiate and uninitiated member of a sect. Focusing on the opposition between expressions and their meanings, this study examines Ụmụakpo- Lejja Okǝti Ọmaba chant, which is a heroic and masculine performance that takes place in the Okǝti (masking enclosure of the deity) of Umuakpo village square in Lejja town of Enugu State, Nigeria. The mystified language promotes discrimination among initiates, non- initiates, and women. Ọmaba is a popular fertility Deity among the Nsukka-Igbo extraction and Egara Ọmaba (Ọmaba chant) generally applies to the various chants performed to honour the deity during its periodical stay on earth. Using Schleiermacher’s Literary Hermeneutics Approach of the methodical practice of interpretation, the metaphorical language of the performance is interpreted to reveal the thoughts and the ideology behind the performance in totality. Among the Findings is that the textual language of Ụmụakpo- Lejja Okǝti Ọmaba chant is almost impossible without authorial and member’s interpretation and therefore, they are capable of initiating discriminatory perception of a non-initiate as a weakling or a woman. Keywords: Ọmaba chant, Ụmụakpo-Lejja, language, power, hermeneutics Introduction Beyond the primary function of language, which is the expression and communication of one’s ideas, a language is also a tool for power, segregation, and division in society. -

An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture

An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture Peter Breunig & Nicole Rupp Abstract Résumé Until recently the Nigerian Nok Culture had primarily Jusqu’à récemment, la Culture de Nok au Nigeria était surtout been known for its terracotta sculptures and the existence connue pour ses sculptures en terre cuite et l’existence de la of iron metallurgy, providing some of the earliest evidence métallurgie du fer, figurant parmi les plus anciens témoignages for artistic sculpting and iron working in sub-Saharan connus de sculpture artistique et du travail du fer en Afrique Africa. Research was resumed in 2005 to understand the sub-saharienne. De nouvelles recherches ont été entreprises en Nok Culture phenomenon, employing a holistic approach 2005 afin de mieux comprendre le phénomène de la Culture de in which the sculptures and iron metallurgy remain central, Nok, en adoptant une approche holistique considérant toujours but which likewise covers other archaeological aspects les sculptures et la métallurgie comme des éléments centraux including chronology, settlement patterns, economy, and mais incluant également d’autres aspects archéologiques tels the environment as key research themes. In the beginning que la chronologie, les modalités de peuplement, l’économie of this endeavour the development of social complexity et l’environnement comme des thèmes de recherche essentiels. during the duration of the Nok Culture constituted a focal Ces travaux ont initialement été articulés autour du postulat point. However, after nearly ten years of research and an d’un développement de la complexité sociale pendant la abundance of new data the initial hypothesis can no longer période couverte par la Culture de Nok. -

Last April, Saaam Met in Phoenix, Arizona. a Number of Issues Were Raised at the Business Meeting

NYAME AKUMA No. 30 EDITORIAL Last April, SAAAm met in Phoenix, Arizona. A number of issues were raised at the business meeting (see Pamela Willoughby's report which follows this editorial), and at a meeting of the newly constituted Executive Committee (minus the Editor who was unable to attend the Phoenix meetings) several of these recommendations were adopted. Thus, effective immediately, the following changes have been made to the structure of both the organization and Nyame Akum . 1. SAAAm is henceforth to be called the Society of Afiicanist Archaeologists (SAFA). 2. The editorial office of Nyame Akuma will remain at the University of Alberta, but subscriptions will now be dealt with by SAFA, at the University of Florida in Gainesville (see opposite page for details). 3. The cost of an annual subscription will rise to US$20, with a reduced rate of US$15 for bona fi& students. Thus, what has always been implicit is now explicit: membership in SAFA will include a subscription to Nyame Akuma (and vice versa). A small proportion of the increased cost will allow SAFA to subsidize separate mailings (e.g. meeting announcements, renewal notices). Furthermore, by relieving the editors of the burden of managing subscriptions, we hope to ensure that NA appears more regularly - in NovemberIDecember and MayIJune . While I am concerned by the response from subscribers overseas (to whom the increased cost may be seen as onerous, and to whom membership in SAFA is likely to be less attractive than to North Americans), I believe these changes are necessary. It is no longer possible to manage Nyame Akuma effectively in the way we have had to until now. -

Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp

NYAME AKUMA No. 73 June 2010 NIGERIA in the production of abundant and beautiful clay figu- rines. Its enigmatic character was underlined by the Outline of a New Research Project lack of any known precursor or successors leaving on the Nok Culture of Central the Nok Culture as a flourishing but totally isolated Nigeria, West Africa phenomenon in the archaeological sequence of the region. Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp Another surprise was the discovery of iron- smelting furnaces in Nok contexts, and at that time Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp amongst the earliest evidence of metallurgy in sub- Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main Saharan Africa (Fagg 1968; Tylecote 1975). The com- Institut für Archäologische bination of early iron and elaborated art – in our west- Wissenschaften ern understanding – demonstrated the potential of Grüneburgplatz 1 the Nok Culture with regard to metallurgical origins 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany and the emergence of complex societies. emails: [email protected], [email protected] However, no one continued with the work of Bernard Fagg. Instead of scientific exploration, the Nok Culture became a victim of illegal diggings and internationally operating art dealers. The result was Introduction the systematic destruction of numerous sites and an immense loss for science. Most Africanist archae- Textbooks on African archaeology and Afri- ologists are confronted with damage caused by un- can art consider the so-called Nok Culture of central authorized diggings for prehistoric art, but it appears Nigeria for its early sophisticated anthropomorphic as if Nok was hit the hardest. Based on the extent of and zoomorphic terracotta figurines (Figures 1 and damage at numerous sites that we have seen in Ni- 2), and usually they emphasize the absence of con- geria, and according to the reports of those who had textual information and thus their social and cultural been involved in the damage, many hundreds if not purpose (Garlake 2002; Phillipson 2005; Willett 2002). -

Tourism As a Tool for Re-Branding Nigeria

International Journal of Research in Arts and Social Sciences Vol 4 Tourism As A Tool For Re-Branding Nigeria Joshua Okenwa Uzuegbu Abstract This research appraises the image crisis in Nigeria and the effort of successive governments, starting from the period of independence to the present dispensation, towards cleaning up of the wrong perception of the country. The study observes that, among other efforts at achieving successful rebranding, tourism is a veritable tool. Thus, some tourism resources in Nigeria were analyzed so as to show how useful they are in the Nigerian rebranding project. Introduction One may be tempted to ask, whether Nigeria actually needs to be re-branded? If the answer is in the affirmative, then what is the effective tool to achieve this? This is the question this paper tries to address. It does this by taking a look at the level of damage inflicted to the image of Nigeria by the activities of few unscrupulous individuals. A review of the activities in the political, social, economic and other spheres of the national life reveals that the country’s negative image, especially in the international arena is informed by negative activities of few in these sectors. This does not mean that majority of Nigerians are not meaningfully engaged in productive ventures that contribute positively to the development of humanity. The fact remains that the international media either by omission or commission have chosen to ignore the positive contributions of these majority, and focused attention on the shortcomings of the few to give the country a bad name. Professor Dora Akunyili, former Minister of Information and Communication and the initiator of re-branding project, while briefing the media on the imperative of this project, observed that the programme is a new chapter in Nigeria’s attempt to take conscious steps at redefining the nation. -

9781107064607 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06460-7 — The Yoruba from Prehistory to the Present Aribidesi Usman , Toyin Falola Index More Information 491 Index abà 45 Apa I 38 Abdulsalam Abubakar 390 Apala 315 àbíkú 278 Ara War 75 Abinu 17 archaeological evidence 4 , 19 , 41 , 51 , abolition laws 214 52 , 59 , 61 , 74 , 266 aboriginal 108 Ilare 96 abulé 46 , see also village Olle 112 aceramic phase 32 Owu 92 Action Group 362 Oyo- Ile 81 activism, women 341 , 356 Archaic Period 43 Adegoke Adelabu 353 architecture, slaves 233 , 238 Ade Obayemi 38 , 103 ar ẹ m ọ 121 Adósùu Sango 304 Are- Ona- Kakanfo 120 , 151 , 153 , 221 Afonja 151 , 161 , 221 , 431 , 432 àtíbàbà 46 Africanism 229 Atlantic trade 141 , 150 , 205 , 206 , agannigan 157 208 , 215 àgbà egungun 281 disrupted 144 Agbekoya Rebellion 372 authority 121 Agbonmiregun 1 extension 217 Agonnigon 111 autochthonous 4 , 103 , 109 agriculture 40 , 243 – 247 , 417 Awole 151 , 161 Aguda 238 ahéré 47 Babalawo 219 , 231 , 275 , 291 , 294 , Ahmed Baba 4 299 , 300 Ajaka 93 Badagry 38 Aja kingdom 14 Bariba 14 , 16 ajele 123 , 130 , 153 , 200 Basorun Gaha 151 , 221 , 431 Ajasepo 104 Bayarabe 4 Ajibod ẹ 33 beads 75 , 124 , 266 , 310 , see also Ajibosin 88 glass beads Aku 5 , 235 Benin 1 , 53 , 74 , 141 , 143 , 295 , 298 Akure 25 , 224 Ilorin 266 Alaai n Ajagbo 118 Biafra 369 Aladura churches 425 , 426 Bight of Benin 4 , 75 , 141, 146 , Alale (ruler of Idasin) 3 207 , 211 All Progressive Congress (APC) 399 boundary markers 46 Al- Salih 221 brass and bronze sculptures 63 , 67 , 298 ancestors 280 Brazil 207 -

Insight from Lejja Iron Smelting Community, Enugu State, Nigeria

MUSIC AS AN INSTRUMENT OF PUNISHMENT IN TRADITIONAL IGBO SOCIETY: INSIGHT FROM LEJJA IRON SMELTING COMMUNITY, ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA. By Christian Chukwuma Opata, and Sam Kenneth Iheanyi Chukwu, PhD Abstract: Music is a specially intended sound that demands mental ingenuity as well as production skill specific to it as a specialized (specie-specific) human activity. The logic, didactics and intention of music must be of some predetermined value or benefit to man to warrant the carving out of special time, creative genius and ingenuity, as well as methods and objects of production. Every music as a human product has a life and logic. Among the Lejja people of South-eastern Nigeria, the logic of some of their music is to evoke fear, awe and other disturbing/provocative emotions in their cultural audience. Some of the music is used in their traditional setting to preserve their ancient iron smelting industry. Iron smelting is an ancient practice of extracting blooms from hematite by subjecting the hematite to intensive heating in a rotund mud structure called furnace. In this study, ethnographic data based on many years of field studies and participant observation would be used in conjunction with materials from relevant literatures. Using two songs and the music of a masked spirit omaba, believed to be the societies’ incarnate being, this study would examine how music is used in a traditional Igbo society to preserve and perpetuate the laws associated with iron smelting by serving as media through which verdicts of the community are communicated to those who violated laws relating to the industry and preventing people who may have the same intention with the culprit from performing the same abominable act. -

Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality

UMEÅ PAPERS IN ENGLISH No. 15 Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality edited by Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama Umeå 1992 Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama (eds.) Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality UMEÅ PAPERS IN ENGLISH i No. 15 Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality edited by Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama Umeå 1992 Umeå Papers in English Printed in Sweden by the Printing Office of Umeå University Umeå 1992 ISSN 0280-5391 Table of Contents Raoul Granqvist and Nnadozie Inyama: Introduction Chukwuma Azuonye: Power, Marginality and Womanbeing i n Igbo Oral Narratives Christine N. Ohale: Women in Igbo Satirical Song Afam N. Ebeogu: Feminist Temperament in Igbo Birth Songs Ambrose A. Monye: Women in Nigerian Folklore: Panegyric and Satirical Poems on Women in Anicha Igbo Oral Poetry N. Chidi Okonkwo: Maker and Destroyer: Woman in Aetiological Tales Damian U. Opata: Igbo A ttitude to Women: A Study of a Prove rb Nnadozie Inyama: The "Rebe l Girl" in West African Liter ature: Variations On a Folklore Theme About the writers iii Introduction The idea of a book of essays on West African women's oral literature was first mooted at the Chinua Achebe symposium in February 1990, at Nsukka, Nigeria. Many of the papers dwelt on the image and role of women in contemporary African literature with, of course, particular attention to their inscriptions in Achebe's fiction. We felt, however, that the images of women as they have been presented by both African men and women writers and critics would benefit from being complement ed, fragmented and tested and that a useful, albeit complex, site for this inquiry could be West African oral representations of the female. -

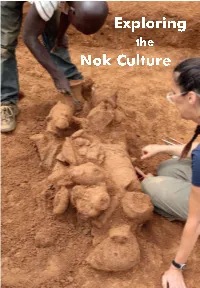

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture Joint Research Project of Goethe University Frankfurt/Main, Germany & National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria A publication of Goethe University, Institute for Archaeological Sciences, African Archaeology and Archaeobotany, Frankfurt/Main, Germany January 2017 Text by Peter Breunig Editing by Gabriele Franke & Annika Schmidt Translation by Peter Dahm Robertson Layout by Kirstin Brauneis-Fröhlich Cover Design by Gabriele Försterling Drawings by Monika Heckner & Barbara Voss Maps by Eyub F. Eyub Photos by Frankfurt Nok Project, Goethe University Printed by Goethe University Computer Center © 2017 Peter Breunig, Goethe University Project Funding Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) Partners Support A Successful Collaboration The NCMM and Goethe University continued their successful collaboration for field research on the Nok Culture Anyone interested in West Africa’s – and in central Nigeria. Starting in 2005, particularly Nigeria’s – prehistory will NCMM has ever since taken care of eventually hear about the Nok Culture. Its administrative matters and arranged artful burnt-clay (terracotta) sculptures the participation of their archaeological make it one of Africa’s best known experts which became valuable members ancient cultures. The Nok sculptures are of the project’s team. More recently, among the oldest in sub-Saharan Africa archaeologists from Ahmadu Bello and represent the origins of the West University in Zaria and Jos University African tradition of portraying people and joined the team. Together, the Nigerian animals. This brochure is a summary of and German archaeologists completed what we know about the Nok Culture and difficult work to gain information on this how we know what we know. -

Chinua Achebe's Short Stories As a Periscope to Igbo Worldview

i CHINUA ACHEBE’S SHORT STORIES AS A PERISCOPE TO IGBO WORLDVIEW BY OGBAJE, JUDITH UNEKWUOJO REG. NO: PG/MA/12/62502 A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LITERARY STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (M. A.) DEGREE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LITERARY STUDIES FACULTY OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA SUPERVISOR: PROF. EZUGU, AMADIHE JUNE, 2014 ii APPROVAL/CERTIFICATION This Project has been read and approved as meeting part of the requirements for the award of Master of Arts (M.A.) Degree in the Department of English and Literary Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Ogbaje, Judith Unekwuojo a post-graduate students of the department with the registration number PG/MA/12/62502 has satisfactorily completed the requirements for the course and research work for the award of Master of Arts (M. A.) Degree. This project to the best of my knowledge has not been submitted to any award giving institution on any grounds. _________________ ___________ ________________ ________ Prof. Ezugu, Amadihe Date Prof. Opata, Damian Date Supervisor Head of Department ______________________ ______________ External Examiner Date iii DEDICATION To my late sister, Pat, who was my mother and guardian. I miss you. May your soul continue to rest in peace. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe God Almighty, the creator of heaven and earth and giver of life a great debt of gratitude for His constant and consistent love and mercy upon me even when I remain inconsistent and for divine strength and grace that has brought me this far. -

Visuality and Representation in Traditional Igbo Uli Body And

345 AFRREV, 10 (2), S/NO 41, APRIL, 2016 An International Multi-disciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 10(2), Serial No.41, April, 2016: 345-357 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v10i2.23 Visuality and Representation in Traditional Igbo Uli Body and Mud Wall Paintings Onwuakpa, Samuel Department of Fine Art and Design University of Port Harcourt, River State, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Phone: 08028871838 Abstract Igbo uli art is a popular creative idiom in south-eastern Nigeria. It is a serves as decorative, ritual and cosmetic art. It does not exhibit any paradox because it has been considered as art that is aesthetically pleasing. Uli art is practiced purely by the womenfolk on human body and mud wall and based on linear configurations. The intention of uli painting is not to create an illusionistic representation of reality. However, it is dependent on both conceptual and perceptual, which results in abstract and non- figurative representations. Uli women painters have produced a voluminous body of work widely distributed throughout Igbo land. However, there is a dearth of uli body and mud wall paintings or decorations as well as their processes of execution as women community art project literature on the corpus of uli art, hence it requires a continuous investigation and scrutiny. This essay therefore provides an insight into the nature and social contest of uli body and mud wall paintings or decorations as well as their processes of execution as women community art project. Introduction Traditional art, according to Kaego Okeke (2002:1), is the chain linking the past with the present.