Uli: Metamorphosis of a Tradition Into Contemporary Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

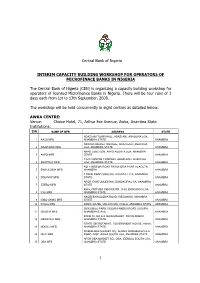

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

History of Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Igboland (1923 – 2010 )

NJOKU, MOSES CHIDI PG/Ph.D/09/51692 A HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN IGBOLAND (1923 – 2010 ) FACULTY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION Digitally Signed by : Content manager’s Name Fred Attah DN : CN = Webmaster’s name O= University of Nigeri a, Nsukka OU = Innovation Centre 1 A HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN IGBOLAND (1923 – 2010) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AND CULTURAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) DEGREE IN RELIGION BY NJOKU, MOSES CHIDI PG/Ph.D/09/51692 SUPERVISOR: REV. FR. PROF. H. C. ACHUNIKE 2014 Approval Page 2 This thesis has been approved for the Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka By --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Rev. Fr. Prof. H. C. Achunike Date Supervisor -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ External Examiner Date Prof Musa Gaiya --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Internal Examiner Date Prof C.O.T. Ugwu -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Internal Examiner Date Prof Agha U. Agha -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Head of Department Date Rev. Fr. Prof H.C. Achunike --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Dean of Faculty Date Prof I.A. Madu Certification 3 We certify that this thesis -

Igbo Folktales and the Idea of Chukwu As Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston From the SelectedWorks of Chukwuma Azuonye April, 1987 Igbo Folktales and the Idea of Chukwu as Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston Available at: http://works.bepress.com/chukwuma_azuonye/76/ ISSN 0794·6961 NSUKKAJOURNAL OF LINGUISTICS AND AFRICAN LANGUAGES NUMBER 1, APRIL 1987 Published by the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Nigeria, Nsukka NOTES ON THE CONTRIBUTORS All but one of the contributors to this maiden issue of The Nsukka Journal of Linguistics and African Languages are members of the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, Univerrsity of Nigeria, Nsukka Mr. B. N. Anasjudu is a Tutor in Applied Linguistics (specialized in Teaching English as a Second Language). Dr. Chukwuma Azyonye is a Senior Lecturer in Oral Literature and Stylistics and Acting Head of Department. Mrs. Clara Ikeke9nwy is a Lecturer in Phonetics and Phonology. Mr. Mataebere IwundV is a Senior Lecturer in Sociolinguistics and Psycholinguistics. Mrs. G. I. Nwaozuzu is a Graduate Assistant in Syntax and Semantics. She also teaches Igbo Literature. Dr. P. Akl,ljYQQbi Nwachukwu is a Senior Lecturer in Syntax and Semantics. Professor Benson Oluikpe is a Professor of Applied and Comparative Linguistics and Dean of the Faculty of Arts. Mr. Chibiko Okebalama is a Tutor in Literature and Stylistics. Dr. Sam VZ9chukwu is a Senior Lecturer in Oral Literature and Stylistics in the Department of African Languages and Literatures, University of Lagos. ISSN 0794-6961 Nsukka Journal of L,i.nguistics and African Languages Number 1, April 1987 IGBD FOLKTALES AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE IDEA OF CHUKWU AS THE SUPREME GOD OF IGBO RELIGION Chukwuma Azyonye This analysis of Igbo folktales reveals eight distinct phases in the evolution of the idea of Chukwu as the supreme God of Igbo religion. -

SIGNIFICANCE of ANIMAL MOTIFS in INDIGENOUS ULI BODY and WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied A

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol. 8, No. 1. June 2019 SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS… Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied Arts Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. [email protected] This article explores the significance of animal motifs in traditional Uli body and wall paintings. A critical assessment and understanding of the philosophical import of animals in African concept of existence is vital for an in-depth appreciation of their (animals’) symbols in indigenous African artworks. This paper attempts to a draw parallel between traditional beliefs concerning certain animals among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria and motifs derived from indigenous Uli body and wall painting. In essence, the article sees animal motifs in Uli body and wall paintings as playing an aesthetic as well as metaphysical roles. Hence I argue that local nuances of religiosity and spirituality have historically imbued the animals with a heightened sense of sacredness in some Igbo communities thus allowing the animals to occupy a mystical space in Igbo cosmology. Introduction The pre-colonial system of knowledge transmission in Africa was not only through oral literature but also through the varied artistic traditions that survived from one generation to the other. The rich heritage of ancient Egyptian arts (including the hieroglyphs), the numerous Neolithic rock paintings and engravings found in Northern Africa, which dates back to 5000 and 2000 BCE respectively were mainly symbolic of vital occurrences of the past, documented through art (Getlein 2002: 335). -

Okanga Royal Drum: the Dance for the Prestige and Initiates Projecting Igbo Traditional Religion Through Ovala Festival in Aguleri Cosmolgy

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.8, No. 3, pp.19-49, March 2020 Published by ECRTD-UK Print ISSN: 2052-6350(Print), Online ISSN: 2052-6369(Online) OKANGA ROYAL DRUM: THE DANCE FOR THE PRESTIGE AND INITIATES PROJECTING IGBO TRADITIONAL RELIGION THROUGH OVALA FESTIVAL IN AGULERI COSMOLGY Madukasi Francis Chuks, PhD ChukwuemekaOdumegwuOjukwu University, Department of Religion & Society. Igbariam Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria. PMB 6059 General Post Office Awka. Anambra State, Nigeria. Phone Number: +2348035157541. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: No literature I have found has discussed the Okanga royal drum and its elements of an ensemble. Elaborate designs and complex compositional ritual functions of the traditional drum are much encountered in the ritual dance culture of the Aguleri people of Igbo origin of South-eastern Nigeria. This paper explores a unique type of drum with mystifying ritual dance in Omambala river basin of the Igbo—its compositional features and specialized indigenous style of dancing. Oral tradition has it that the Okanga drum and its style of dance in which it figures originated in Aguleri – “a farming/fishing Igbo community on Omambala River basin of South- Eastern Nigeria” (Nzewi, 2000:25). It was Eze Akwuba Idigo [Ogalagidi 1] who established the Okanga royal band and popularized the Ovala festival in Igbo land equally. Today, due to that syndrome and philosophy of what I can describe as ‘Igbo Enwe Eze’—Igbo does not have a King, many Igbo traditional rulers attend Aguleri Ovala festival to learn how to organize one in their various communities. The ritual festival of Ovala where the Okanga royal drum features most prominently is a commemoration of ancestor festival which symbolizes kingship and acts as a spiritual conduit that binds or compensates the communities that constitutes Eri kingdom through the mediation for the loss of their contact with their ancestral home and with the built/support in religious rituals and cultural security of their extended brotherhood. -

Igbo Man's Belief in Prayer for the Betterment of Life Ikechukwu

Igbo man’s Belief in Prayer for the Betterment of Life Ikechukwu Okodo African & Asian Studies Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Abstract The Igbo man believes in Chukwu strongly. The Igbo man expects all he needs for the betterment of his life from Chukwu. He worships Chukwu traditionally. His religion, the African Traditional Religion, was existing before the white man came to the Igbo land of Nigeria with his Christianity. The Igbo man believes that he achieves a lot by praying to Chukwu. It is by prayer that he asks for the good things of life. He believes that prayer has enough efficacy to elicit mercy from Chukwu. This paper shows that the Igbo man, to a large extent, believes that his prayer contributes in making life better for him. It also makes it clear that he says different kinds of prayer that are spontaneous or planned, private or public. Introduction Since the Igbo man believes in Chukwu (God), he cannot help worshipping him because he has to relate with the great Being that made him. He has to sanctify himself in order to find favour in Chukwu. He has to obey the laws of his land. He keeps off from blood. He must not spill blood otherwise he cannot stand before Chukwu to ask for favour and succeed. In spite of that it can cause him some ill health as the Igbo people say that those whose hands are bloody are under curses which affect their destines. The Igboman purifies himself by avoiding sins that will bring about abominations on the land. -

The Influence of the Supernatural in Elechi Amadi’S the Concubine and the Great Ponds

THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE AND THE GREAT PONDS BY EKPENDU, CHIKODI IFEOMA PG/MA/09/51229 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LITERARY STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. SUPERVISOR: DR. EZUGU M.A A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (M.A) IN ENGLISH & LITERARY STUDIES TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. JANUARY, 2015 i TITLE PAGE THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE AND THE GREAT PONDS BY EKPENDU, CHIKODI IFEOMA PG /MA/09/51229 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH & LITERARY STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. JANUARY, 2015 ii CERTIFICATION This research work has been read and approved BY ________________________ ________________________ DR. M.A. EZUGU SIGNATURE & DATE SUPERVISOR ________________________ ________________________ PROF. D.U.OPATA SIGNATURE & DATE HEAD OF DEPARTMENT ________________________ ________________________ EXTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE & DATE iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my dear son Davids Smile for being with me all through the period of this study. To my beloved husband, Mr Smile Iwejua for his love, support and understanding. To my parents, Elder & Mrs S.C Ekpendu, for always being there for me. And finally to God, for his mercies. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks go to the Almighty God for his steadfast love and for bringing me thus far in my academics. To him be all the glory. My Supervisor, Dr Mike A. Ezugu who patiently taught, read and supervised this research work, your well of blessings will never run dry. My ever smiling husband, Mr Smile Iwejua, your smile and support took me a long way. -

Purple Hibiscus

1 A GLOSSARY OF IGBO WORDS, NAMES AND PHRASES Taken from the text: Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Appendix A: Catholic Terms Appendix B: Pidgin English Compiled & Translated for the NW School by: Eze Anamelechi March 2009 A Abuja: Capital of Nigeria—Federal capital territory modeled after Washington, D.C. (p. 132) “Abumonye n'uwa, onyekambu n'uwa”: “Am I who in the world, who am I in this life?”‖ (p. 276) Adamu: Arabic/Islamic name for Adam, and thus very popular among Muslim Hausas of northern Nigeria. (p. 103) Ade Coker: Ade (ah-DEH) Yoruba male name meaning "crown" or "royal one." Lagosians are known to adopt foreign names (i.e. Coker) Agbogho: short for Agboghobia meaning young lady, maiden (p. 64) Agwonatumbe: "The snake that strikes the tortoise" (i.e. despite the shell/shield)—the name of a masquerade at Aro festival (p. 86) Aja: "sand" or the ritual of "appeasing an oracle" (p. 143) Akamu: Pap made from corn; like English custard made from corn starch; a common and standard accompaniment to Nigerian breakfasts (p. 41) Akara: Bean cake/Pea fritters made from fried ground black-eyed pea paste. A staple Nigerian veggie burger (p. 148) Aku na efe: Aku is flying (p. 218) Aku: Aku are winged termites most common during the rainy season when they swarm; also means "wealth." Akwam ozu: Funeral/grief ritual or send-off ceremonies for the dead. (p. 203) Amaka (f): Short form of female name Chiamaka meaning "God is beautiful" (p. 78) Amaka ka?: "Amaka say?" or guess? (p. -

Symbols of Communication: the Case of Àdìǹkrá and Other Symbols of Akan

The International Journal - Language Society and Culture URL: www.educ.utas.edu.au/users/tle/JOURNAL/ ISSN 1327-774X Symbols of Communication: The Case of Àdìǹkrá and Other Symbols of Akan Charles Marfo, Kwame Opoku-Agyeman and Joseph Nsiah Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana Abstract The Akan people of Ghana have a number of coined symbols that express various forms of infor- mation based on socio-cultural knowledge. These symbols of expression are collectively called àdìǹkrá. There are related symbols of oral orientation that seem to play the same role as àdìǹkrá. In this paper, we explore the àdìǹkrá symbols and the related ones, the individual messages they en- code and their significance in the Akan society. It is explained that most of these symbols are inspired on creation and man-made objects. Some others are also proverb-based. The àdìǹkrá symbols in par- ticular constitute a medium of objective and deep-seated socio-cultural knowledge of the Akan people. We contend that, like words and actions, the symbols represent and send various distinctive messag- es that are indisputably accepted by people who know them. The use of àdìǹkrá and the related sym- bols in modern textiles, language and literature are also discussed. Keywords: Adinkra, Akan, Communication, Culture, Symbols of expression. Introduction A symbol could be defined as a creation that represents a message, a thought, proverb etc. When a set of symbols is attributed to a particular group of people belonging to a particular culture, these symbols become a window to the understanding of aspects of their culture. -

Language and Identity: a Case of Igbo Language, Nigeria Igbokwe

LANGUAGE AND IDENTITY: A CASE OF IGBO LANGUAGE, NIGERIA IGBOKWE, BENEDICT NKEMDIRIM DIRECTORATE OF GENERAL STUDIES, FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, OWERRI IMO STATE, NIGERIA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Language is the most important information and communication characteristics of all the human beings. Language is power as well as a great instrument for cultural preservation. The world community is made up of many languages and each of these languages is being used to identify one speech community or race. Unfortunately, it has been observed that Igbo language is fast deteriorating as a means of communication among the Igbo. The Igbo have embraced foreign languages in place of their mother tongue (Igbo language). This paper is therefore aimed at highlighting the importance of Igbo language as a major form of Igbo identity. This study will immensely benefit students, researchers and Igbo society in general. A framework was formulated to direct research effort on the development and study of Igbo language, the relationship between Igbo language and culture, the importance of Igbo language as a major form of Igbo identity, the place of Igbo language in the minds of the present Igbo and factors militating against the growth of the language and finally recommendations were given. Keywords: Language, Identity, Culture, Communication, Speech Communication Introduction Language is the most important information and communication characteristics of all human beings. Language is power as well as great weapon for cultural preservation. Only humans have spoken and written languages, and language is the key note of culture because without it, culture does not exist. It is the medium of language that conveys the socio-political, economic and religious thoughts from individual to individual, and from generation to generation. -

Igbo Folktales and the Evolution of the Idea of Chukwu As the Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston From the SelectedWorks of Chukwuma Azuonye April, 1987 Igbo Folktales and the Evolution of the Idea of Chukwu as the Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston Available at: https://works.bepress.com/chukwuma_azuonye/70/ ISSN 0794-6961 Nsukka Journal of LJnguistics and African Languages Number 1, April 1987 IGBO FOLKTALES AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE IDEA OF CHUKWU AS THE SUPREME GOD OF IGBO RELIGION Chukwuma AZ\lonye This analysis of Igbo folktales reveals eight distinct phases in the evolution of the idea of Chukwu as the supreme God of Igbo religion. In the first phase, dating back to primeval times, the Igbo recognized several supreme nature deities in various domains. This was followed by a phase of the undisputed supremacy of )Ud (the Earth Goddess) as supreme deity. Traces of that primeval dominance persist till today in some parts of Igboland. The third phase was one of rivalry over supremacy· between Earth and Sky, possibly owing to influences from religious traditions founded on the belief in a supreme sky-dwelling God. In the fourth and fifth phases, the idea of Chukwu as supreme. deity was formally established by the Nri and Ar? respectively in support of their.hegemonic'enterprise in Igbo- land. The exploitativeness of the ArC? powez- seems to .have resulted in the debasement of the idea of Chukwu as supreme God in the Igbo mind, hence the satiric. and.~ images of the anthropo- morphic supreme God in various folktales from the .sixth phase. The sev~nth phase saw the selection, adoption and adaptation of some of the numerous ideas of supreme God founn bv the Christian missionaries in their efforts to propagate Christianity in the idiom of the people. -

A Socio- Economic History of Alcohol in Southeastern Nigeria Since 1890

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background to the Study Alcohol has various socio-economic and cultural functions among the people of southeastern Nigeria. It is used in rituals, marriages, oath taking, festivals and entertainment. It is presented as a mark of respect and dignity. The basic alcoholic beverage produced and consumed in the area was palm -wine tapped from the oil palm tree or from the raffia- palm. Korieh notes that, from the fifteenth century contacts between the Europeans and peoples of eastern Nigeria especially during the Atlantic slave trade era, brought new varieties of alcoholic beverages primarily, gin and whisky.1 Thus, beginning from this period, gins especially schnapps from Holland became integrated in local culture of the peoples of Eastern Nigeria and even assumed ritual position.2 From the 1880s, alcohol became accepted as a medium of exchange for goods and services and a store of wealth.3 By the early twentieth century, alcohol played a major role in the Nigerian economy as one third of Nigeria‘s income was derived from import duties on liquor.4 Nevertheless, prior to the contact of the people of Southern Nigeria with the Europeans, alcohol was derived mainly from the oil palm and raffia palm trees which were numerous in the area. These palms were tapped and the sap collected and drunk at various occasions. From the era of the Trans- Atlantic slave trade, the import of gin, rum and whisky became prevalent.These were used in ex-change for slaves and to pay comey – a type of gratification to the chiefs. Even with the rise of legitimate trade in the 19th century alcoholic beverages of various sorts continued to play important roles in international trade.5 Centuries of importation of gin into the area led to the entrenchment of imported gin in the culture of the people.