Nok Early Iron Production in Central Nigeria – New Finds and Features

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture

An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture Peter Breunig & Nicole Rupp Abstract Résumé Until recently the Nigerian Nok Culture had primarily Jusqu’à récemment, la Culture de Nok au Nigeria était surtout been known for its terracotta sculptures and the existence connue pour ses sculptures en terre cuite et l’existence de la of iron metallurgy, providing some of the earliest evidence métallurgie du fer, figurant parmi les plus anciens témoignages for artistic sculpting and iron working in sub-Saharan connus de sculpture artistique et du travail du fer en Afrique Africa. Research was resumed in 2005 to understand the sub-saharienne. De nouvelles recherches ont été entreprises en Nok Culture phenomenon, employing a holistic approach 2005 afin de mieux comprendre le phénomène de la Culture de in which the sculptures and iron metallurgy remain central, Nok, en adoptant une approche holistique considérant toujours but which likewise covers other archaeological aspects les sculptures et la métallurgie comme des éléments centraux including chronology, settlement patterns, economy, and mais incluant également d’autres aspects archéologiques tels the environment as key research themes. In the beginning que la chronologie, les modalités de peuplement, l’économie of this endeavour the development of social complexity et l’environnement comme des thèmes de recherche essentiels. during the duration of the Nok Culture constituted a focal Ces travaux ont initialement été articulés autour du postulat point. However, after nearly ten years of research and an d’un développement de la complexité sociale pendant la abundance of new data the initial hypothesis can no longer période couverte par la Culture de Nok. -

The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari

The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari Tanja M. Männel & Peter Breunig Abstract Résumé Since their discovery in the mid-20th century, the terracottas Depuis leur découverte au milieu du XXe siècle, les sculptures of the Nok Culture in Central Nigeria, which represent the de la culture Nok au Nigeria central sont connues, au-delà des earliest large-scale sculptural tradition in Sub-Saharan Af- spécialistes, comme la tradition la plus ancienne des sculptures rica, have attracted attention well beyond specialist circles. de grande taille de l’Afrique subsaharienne. Toutefois leur Their cultural context, however, remained virtually unknown contexte culturel resta inconnu pour longtemps, dû à l’absence due to the lack of scientifically recorded, meaningful find de situations de fouille pertinentes démontrées scientifiquement. conditions. Here we will describe an archaeological feature Ici nous décrivons une découverte, trouvée à Pangwari, lieu uncovered at the almost completely excavated Nok site of de découverte Nok, située dans le sud de l’état de Kaduna, qui Pangwari, a settlement site located in the South of Kaduna fourni des informations suffisantes montrant que des sculptures State, which provided sufficient information to conclude that en terre cuite ont été détruites délibérément et puis déposées, ce the terracotta sculptures had been deliberately destroyed qui, par conséquent, met en évidence exemplaire l’aspect rituel and then deposited, emphasising the ritual aspect of early de l’ancien art plastique africain. Auparavant, des observations African figurative art. similaires ont été faites sur d’autres sites de recherches. Similar observations were made at various other sites Or les sculptures en terre cuite découvertes à Pangwari we had examined previously. -

Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp

NYAME AKUMA No. 73 June 2010 NIGERIA in the production of abundant and beautiful clay figu- rines. Its enigmatic character was underlined by the Outline of a New Research Project lack of any known precursor or successors leaving on the Nok Culture of Central the Nok Culture as a flourishing but totally isolated Nigeria, West Africa phenomenon in the archaeological sequence of the region. Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp Another surprise was the discovery of iron- smelting furnaces in Nok contexts, and at that time Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp amongst the earliest evidence of metallurgy in sub- Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main Saharan Africa (Fagg 1968; Tylecote 1975). The com- Institut für Archäologische bination of early iron and elaborated art – in our west- Wissenschaften ern understanding – demonstrated the potential of Grüneburgplatz 1 the Nok Culture with regard to metallurgical origins 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany and the emergence of complex societies. emails: [email protected], [email protected] However, no one continued with the work of Bernard Fagg. Instead of scientific exploration, the Nok Culture became a victim of illegal diggings and internationally operating art dealers. The result was Introduction the systematic destruction of numerous sites and an immense loss for science. Most Africanist archae- Textbooks on African archaeology and Afri- ologists are confronted with damage caused by un- can art consider the so-called Nok Culture of central authorized diggings for prehistoric art, but it appears Nigeria for its early sophisticated anthropomorphic as if Nok was hit the hardest. Based on the extent of and zoomorphic terracotta figurines (Figures 1 and damage at numerous sites that we have seen in Ni- 2), and usually they emphasize the absence of con- geria, and according to the reports of those who had textual information and thus their social and cultural been involved in the damage, many hundreds if not purpose (Garlake 2002; Phillipson 2005; Willett 2002). -

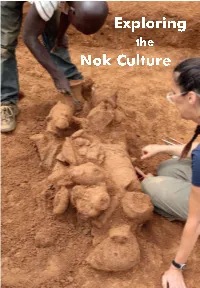

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture Joint Research Project of Goethe University Frankfurt/Main, Germany & National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria A publication of Goethe University, Institute for Archaeological Sciences, African Archaeology and Archaeobotany, Frankfurt/Main, Germany January 2017 Text by Peter Breunig Editing by Gabriele Franke & Annika Schmidt Translation by Peter Dahm Robertson Layout by Kirstin Brauneis-Fröhlich Cover Design by Gabriele Försterling Drawings by Monika Heckner & Barbara Voss Maps by Eyub F. Eyub Photos by Frankfurt Nok Project, Goethe University Printed by Goethe University Computer Center © 2017 Peter Breunig, Goethe University Project Funding Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) Partners Support A Successful Collaboration The NCMM and Goethe University continued their successful collaboration for field research on the Nok Culture Anyone interested in West Africa’s – and in central Nigeria. Starting in 2005, particularly Nigeria’s – prehistory will NCMM has ever since taken care of eventually hear about the Nok Culture. Its administrative matters and arranged artful burnt-clay (terracotta) sculptures the participation of their archaeological make it one of Africa’s best known experts which became valuable members ancient cultures. The Nok sculptures are of the project’s team. More recently, among the oldest in sub-Saharan Africa archaeologists from Ahmadu Bello and represent the origins of the West University in Zaria and Jos University African tradition of portraying people and joined the team. Together, the Nigerian animals. This brochure is a summary of and German archaeologists completed what we know about the Nok Culture and difficult work to gain information on this how we know what we know. -

Trabajo Fin De Grado

Trabajo Fin de Grado Título del trabajo: Las terracotas de la cultura Nok de Nigeria English tittle: The Nigeria Nok culture terracottas Autor Federico Beltrán Moreno Director/es José Luis Pano Gracia FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS Año 2017 ÍNDICE RESUMEN…………………………………………………………………………….Pág. 3 1. INTRODUCCIÓN 1.1. JUSTIFICACIÓN DEL TEMA…………………………………………...Pág. 3 1.2. ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN……………………………………………Pág. 4 1.3. METODOLOGÍA APLICADA…………………………………………...Pág. 6 1.4. OBJETIVOS……………………………………………………………….Pág. 7 2. LAS TERRACOTAS DE LA CULTURA NOK 2.1. EL NACIMIENTO DE LA ESCULTURA NEGROAFRICANA……......Pág. 7 2.2. EL DESCUBRIMIENTO DEL ARTE NOK……………………………..Pág. 10 2.3. CRONOLOGIAS DEL ARTE NOK……………………………………...Pág. 13 2.4. CARACTERÍSTICAS FORMALES DE LAS TERRACOTAS……….....Pág. 14 2.5. FUNCIÓN Y USO DE LAS PIEZAS……………………………………..Pág. 18 2.6. VARIEDAD DE ESTILOS ESCULTÓRICOS EN NIGERIA……………Pág. 20 2.7. LA PRESENCIA DE LAS TERRACOTAS NOK EN ESPAÑA. LA FUNDACIÓN JIMÉNEZ-ARELLANO ALONSO………………………..Pág. 23 3. CONCLUSIONES…………………………………………………………………...Pág. 25 4. BIBLIOGRAFÍA……………………………………………………………………..Pág. 27 5. ILUSTRACIONES.…………………………………………………………………..Pág. 29 6. APÉNDICE DE OBRAS……………………………………………………………..Pág. 46 2 RESUMEN En este trabajo de fin de grado se ofrece una visión global sobre lo más importante que conocemos hasta el momento presente acerca de la cultura Nok del norte de Nigeria. Repasaremos desde los inicios de su descubrimiento, pasando luego por los yacimientos más importantes de la misma, y finalmente hablaremos tanto de las características formales de las propias terracotas como de la variedad de las mismas. Tras ello, y partir de las teorías más relevantes, realizaremos una síntesis sobre el posible uso y significado de estas piezas. 1. -

A Chronology of the Central Nigerian Nok Culture – 1500 BC to the Beginning of the Common Era

A Chronology of the Central Nigerian Nok Culture – 1500 BC to the Beginning of the Common Era Gabriele Franke Abstract Résumé The Central Nigerian Nok Culture and its well-known terra- Dans le centre du Nigeria, la culture de Nok ainsi que les cotta figurines have been the focus of a joint research project célèbres sculptures en terre cuite qui lui sont associées font between the Goethe University Frankfurt and the National l’objet depuis 2005 d’un projet de recherche conjoint entre la Commission for Museums and Monuments in Nigeria since Goethe-Universität de Francfort et la Commission pour les 2005. One major research question concerns chronological Musées et Monuments du Nigeria. Une question de recherche aspects of the Nok Culture, for which a period from around the essentielle concerne les aspects chronologiques de cette culture, middle of the first millennium BC to the first centuries AD had que des travaux antérieurs ont permis de rattacher à une been suggested by previous investigations. This paper presents période comprise entre le milieu du premier millénaire BC et les and discusses the radiocarbon and luminescence dates ob- premiers siècles de notre ère. Cet article présente et commente tained by the Frankfurt Nok project. Combining the absolute les dates radiocarbones et par thermoluminescence obtenues dates with the results of a comprehensive pottery analysis, a dans le cadre du projet Nok de l’Université de Francfort. chronology for the Nok Culture has been developed. An early Une chronologie pour la culture de Nok est proposée à partir phase of the Nok Culture’s development begins around the d’une approche combinant les dates absolues avec les résultats middle of the second millennium BC. -

A Chronology of the Central Nigerian Nok Culture – 1500 BC to the Beginning of the Common Era

A Chronology of the Central Nigerian Nok Culture – 1500 BC to the Beginning of the Common Era Gabriele Franke Abstract Résumé The Central Nigerian Nok Culture and its well-known terra- Dans le centre du Nigeria, la culture de Nok ainsi que les cotta figurines have been the focus of a joint research project célèbres sculptures en terre cuite qui lui sont associées font between the Goethe University Frankfurt and the National l’objet depuis 2005 d’un projet de recherche conjoint entre la Commission for Museums and Monuments in Nigeria since Goethe-Universität de Francfort et la Commission pour les 2005. One major research question concerns chronological Musées et Monuments du Nigeria. Une question de recherche aspects of the Nok Culture, for which a period from around the essentielle concerne les aspects chronologiques de cette culture, middle of the first millennium BC to the first centuries AD had que des travaux antérieurs ont permis de rattacher à une been suggested by previous investigations. This paper presents période comprise entre le milieu du premier millénaire BC et les and discusses the radiocarbon and luminescence dates ob- premiers siècles de notre ère. Cet article présente et commente tained by the Frankfurt Nok project. Combining the absolute les dates radiocarbones et par thermoluminescence obtenues dates with the results of a comprehensive pottery analysis, a dans le cadre du projet Nok de l’Université de Francfort. chronology for the Nok Culture has been developed. An early Une chronologie pour la culture de Nok est proposée à partir phase of the Nok Culture’s development begins around the d’une approche combinant les dates absolues avec les résultats middle of the second millennium BC. -

Tourism Potentials of Taruga Historical Iron Smelting Site Obinna

Tourism Potentials of Taruga Historical Iron Smelting Site 12 Tourism Potentials of Taruga Historical Iron Smelting Site Obinna Emeafor and Pat Uche Okpoko Department of Archaeology and Tourism University of Nigeria, Nsukka Email: [email protected] Abstract Archaeological sites are places where spatial clustering of various forms of archeological data such as artifacts, ecofacts and features are found in their original context. They have potentials for tourism since they contain relics of ancient civilization, for example, we can talk about Masada World Heritage Site - the biggest archaeological site, and one of the most famous tourism destinations in Israel. Consequently, the relationship between Tourism and Archaeology is increasingly being recognized, especially in the twenty first century where tourism has become an implacable socio-economic force. And following from the aforementioned, “federal and state agencies often view tourism as a way to use heritage resources in economic development” (Anyon, Ferguson and Welch in McManamon and Hatton eds. 2000:133). It is in line with this that Alagoa (1988, cited in Okpoko, A.I and Okpoko, P.U. 2002:57) affirmed that archaeological and historical data are part of the patrimony that must sustain Nigeria’s tourism and economy. This paper examines the tourism potentials of Taruga, a famous historical iron smelting site within the Nok culture complex, using qualitative approaches. The paper argues that given its multifarious cultural product, natural attractions and proximity to the Federal Capital Territory, Taruga can be a viable tourism haven if well harnessed. Key terms: archaeological sites, tourism potentials, Taruga. Introduction In Nigeria, many archaeological sites have been lost to development projects (see, for example, Kimbers 2006). -

Archaeobotanical Studies at Nok Sites: Leiocarpa Lead Us to Presume That Wood Was Col- an Interim Report Lected from Isoberlinia Woodland

NYAME AKUMA No. 71 JUNE 2009 NIGERIA Phyllantaceae together with typical Sudanian spe- cies like Faidherbia albida and Anogeissus Archaeobotanical Studies at Nok sites: leiocarpa lead us to presume that wood was col- an Interim Report lected from Isoberlinia woodland. S. Kahlheber, A. Höhn, and N. Rupp Goethe-University Introduction Institute for Archaeological Sciences Little is known of the Nok culture in Central African Archaeology and Archaeobotany Nigeria, which is defined largely on the basis of its Grüneburgplatz 1 outstanding terracotta figurines. Created in the first 60323 Frankfurt millennium BC1 they constitute the oldest preserved Germany traces of sculptural tradition in Africa outside Egypt E-mail: (Willett 2002: 64) and are regularly included in gen- [email protected] eral pan-African overviews (e.g. Garlake 2002: 109- [email protected] 112; Phillipson 2005: 235-236; Willett 2002: 63-72). [email protected] Within the Nok figurine material at least three styles have been recognized, which might represent re- gional or chronological variations (Jemkur 1992: 72). Abstract These differences, as well as the lack of scientifically Well known for its terracotta art and providing excavated Nok assemblages, have repeatedly pro- some of the earliest evidence for iron technology in voked discussions around the conceptual use of the sub-Saharan Africa, the Nok culture of Central Ni- term “Nok culture” (Jemkur 1992: 72; Shaw 1981: 56), geria has received little archaeological attention for arguing that it is rather an aggregation of cultural many years. Since 2005 a research project at the Goethe traditions, expressed in a certain manner of manufac- University in Frankfurt has focused on the cultural turing terracotta art.