Nok Terra-Cotta Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Socio – Cultural Rejuvenation: a Quest for Architectural Contribution in Kano Cultural Centres, Nigeria

International Journal of Advanced Academic Research | Social and Management Sciences | ISSN: 2488-9849 Vol. 5, Issue 3 (March 2019) SOCIO – CULTURAL REJUVENATION: A QUEST FOR ARCHITECTURAL CONTRIBUTION IN KANO CULTURAL CENTRES, NIGERIA Gali Kabir Umar1 and Danjuma Abdu Yusuf2 1&2Department of Architecture, Kano University of Science and Technology, P.M.B. 3244, Wudil, Kano State, Nigeria *Corresponding Author‟s Email: [email protected] 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT For thousand years, Kano astound visitors with its pleasing landscape full with colorful dresses, leather and art works, commodities, city wall and gates, ponds, mud houses, horsemen, and festivals. However, an attempt has been made to create a theoretical link between human society on earth and culture of individual groups or tribes but none have been found successful, since these theories of cultural synthesis do not encourage creating a unique monument of cultural styles, nevertheless, they help at producing practical theories that will easily be applicable and useful to norms redevelopment and general standard. This study aims to revitalize a forum in a society for cultural expressions known as “Dandali” in Hausa villages and towns which now metamorphosed into the present day cultural centre in Kano and the country at large. The study focuses on the socio- cultural life of Hausa/Fulani which is dominated by various activities; the normal get together, commercial activities and cultural entertainment. It reveals the lack of efficient and functional culture centre in the state since its creation; to preserve traditional and cultural heritage so as not be relegated to the background and be swallowed by its foreign counter parts. -

The Restructuring of Ethnicity in Nigeria

The uses of the past: the restructuring of ethnicity in Nigeria CHAPTER FOR: FROM INVENTION TO AMBIGUITY: THE PERSISTENCE OF ETHNICITY IN AFRICA François G. Richard and Kevin C. MacDonald eds. Left Coast [but not left wing] Press [FINAL VERSION SUBMITTED POST EDITORS COMMENTS] Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0) 7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: Cambridge, 14 August 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction: the growth of indigenous ethnography.............................................................................. 1 2. Anthropologists and the changing nature of ethnography...................................................................... 2 3. Indigenous ethnographic survey: the CAPRO texts ................................................................................ 4 4. Remote origins and claims to identity ....................................................................................................... 6 5. Correlations with the archaeological record ............................................................................................ 7 6. The denial of ethnicity in the academic sphere and some counter-examples ...................................... 10 7. Reinventing ethnicity in the current political climate............................................................................ 11 8. Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................... -

An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture

An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture Peter Breunig & Nicole Rupp Abstract Résumé Until recently the Nigerian Nok Culture had primarily Jusqu’à récemment, la Culture de Nok au Nigeria était surtout been known for its terracotta sculptures and the existence connue pour ses sculptures en terre cuite et l’existence de la of iron metallurgy, providing some of the earliest evidence métallurgie du fer, figurant parmi les plus anciens témoignages for artistic sculpting and iron working in sub-Saharan connus de sculpture artistique et du travail du fer en Afrique Africa. Research was resumed in 2005 to understand the sub-saharienne. De nouvelles recherches ont été entreprises en Nok Culture phenomenon, employing a holistic approach 2005 afin de mieux comprendre le phénomène de la Culture de in which the sculptures and iron metallurgy remain central, Nok, en adoptant une approche holistique considérant toujours but which likewise covers other archaeological aspects les sculptures et la métallurgie comme des éléments centraux including chronology, settlement patterns, economy, and mais incluant également d’autres aspects archéologiques tels the environment as key research themes. In the beginning que la chronologie, les modalités de peuplement, l’économie of this endeavour the development of social complexity et l’environnement comme des thèmes de recherche essentiels. during the duration of the Nok Culture constituted a focal Ces travaux ont initialement été articulés autour du postulat point. However, after nearly ten years of research and an d’un développement de la complexité sociale pendant la abundance of new data the initial hypothesis can no longer période couverte par la Culture de Nok. -

Construing a Relationship Between Northwestern Nigeria Terracotta Sculptures and Those of Nok

CONSTRUING A RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN NORTHWESTERN NIGERIA TERRACOTTA SCULPTURES AND THOSE OF NOK BY M. O. HAMBOLU National Commission for Museums and Monuments ‐ Nigeria Map of sites mentioned in the presentation INTRODUCTION • Terracotta sculptures have been discovered from several culture areas of Nigeria the more prominent ones being Nok, Ife, Sokoto/Katsina (NW) and Calabar. • Based on the present state of our knowledge, Nok is the oldest, with the Northwestern terracotta sites being their near contemporaries. Terracotta sculptures from Calabar area are older than those of Ife. • In this presentation, because of the relative geographical contiguity and the chronological closeness between Nok and the Northwestern terracotta sculptures, an attempt is being made to compare the two sculptural traditions in terms of style, motifs, techniques of production, archaeological contexts, intra and inter site relationships and dates. • It is believed that this long‐term endeavour, would contribute towards an understanding of the nature of relationships among societies that flourished in the Nigerian region during the first millenium BC and first millenium AD. ACTIVITIES AND RESEARCH IN THE NOK CULTURE AREA • Terracotta sculptures from the Nok region have been brought to the limelight through three principal means, namely, accidental discoveries, archaeological excavations and illegal diggings. • In conducting this comparative analysis, we shall – though unfortunate – utilize all sources to enable us have large data to work with. • While the ongoing archaeological work by Breunig’s team is increasing our understanding of the Nok sculptures and the societies that produced them, we shall also utilize the work of Boullier who analyzed about a thousand terracotta sculptures that were looted out of Nigeria to understand their styles, techniques of production and motifs etc. -

The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari

The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari Tanja M. Männel & Peter Breunig Abstract Résumé Since their discovery in the mid-20th century, the terracottas Depuis leur découverte au milieu du XXe siècle, les sculptures of the Nok Culture in Central Nigeria, which represent the de la culture Nok au Nigeria central sont connues, au-delà des earliest large-scale sculptural tradition in Sub-Saharan Af- spécialistes, comme la tradition la plus ancienne des sculptures rica, have attracted attention well beyond specialist circles. de grande taille de l’Afrique subsaharienne. Toutefois leur Their cultural context, however, remained virtually unknown contexte culturel resta inconnu pour longtemps, dû à l’absence due to the lack of scientifically recorded, meaningful find de situations de fouille pertinentes démontrées scientifiquement. conditions. Here we will describe an archaeological feature Ici nous décrivons une découverte, trouvée à Pangwari, lieu uncovered at the almost completely excavated Nok site of de découverte Nok, située dans le sud de l’état de Kaduna, qui Pangwari, a settlement site located in the South of Kaduna fourni des informations suffisantes montrant que des sculptures State, which provided sufficient information to conclude that en terre cuite ont été détruites délibérément et puis déposées, ce the terracotta sculptures had been deliberately destroyed qui, par conséquent, met en évidence exemplaire l’aspect rituel and then deposited, emphasising the ritual aspect of early de l’ancien art plastique africain. Auparavant, des observations African figurative art. similaires ont été faites sur d’autres sites de recherches. Similar observations were made at various other sites Or les sculptures en terre cuite découvertes à Pangwari we had examined previously. -

Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp

NYAME AKUMA No. 73 June 2010 NIGERIA in the production of abundant and beautiful clay figu- rines. Its enigmatic character was underlined by the Outline of a New Research Project lack of any known precursor or successors leaving on the Nok Culture of Central the Nok Culture as a flourishing but totally isolated Nigeria, West Africa phenomenon in the archaeological sequence of the region. Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp Another surprise was the discovery of iron- smelting furnaces in Nok contexts, and at that time Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp amongst the earliest evidence of metallurgy in sub- Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main Saharan Africa (Fagg 1968; Tylecote 1975). The com- Institut für Archäologische bination of early iron and elaborated art – in our west- Wissenschaften ern understanding – demonstrated the potential of Grüneburgplatz 1 the Nok Culture with regard to metallurgical origins 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany and the emergence of complex societies. emails: [email protected], [email protected] However, no one continued with the work of Bernard Fagg. Instead of scientific exploration, the Nok Culture became a victim of illegal diggings and internationally operating art dealers. The result was Introduction the systematic destruction of numerous sites and an immense loss for science. Most Africanist archae- Textbooks on African archaeology and Afri- ologists are confronted with damage caused by un- can art consider the so-called Nok Culture of central authorized diggings for prehistoric art, but it appears Nigeria for its early sophisticated anthropomorphic as if Nok was hit the hardest. Based on the extent of and zoomorphic terracotta figurines (Figures 1 and damage at numerous sites that we have seen in Ni- 2), and usually they emphasize the absence of con- geria, and according to the reports of those who had textual information and thus their social and cultural been involved in the damage, many hundreds if not purpose (Garlake 2002; Phillipson 2005; Willett 2002). -

Ife–Sungbo Archaeological Project: Aims and Objectives

DIRECTORS: IFE –SUNGBO GÉRARD L. CHOUIN, PHD Rapport ADISA B. OGUNFOLAKAN, PHD Introduction generale ARCHAEOLOGICAL A.1 Collaborations / mobilization des moyens Collaborateurs universitaires: MAIN ACADEMIC PARTNERS Etudians PROJECT Institutions PRELIMINARY REPORT ON Financiers EXCAVATIONS AT ITA YEMOO, ILE-IFE, OSUN STATE AND ON RAPID A.2 Urbanisation / la problematique des enceintes pour la chronologie de l’urbanisation en SSESSMENT OF ARTHWORK ITES AT Afrique forestiereA E S EREDO AND ILARA-EPE, LAGOS STATE A.3 L’archeologie d’Ile-Ife JUNE–JULY 2015 A.4 Ita Yemoo: fouilles par Willett, 1957 B. Recherches en Archives Papers of Professor Frank Willett, 1925-2006, Anthropologist, Archaeologist, Professor and Director of the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, 1976-1990 C. Recherches archeologiques C.1. Pavements MAIN FUNDING AGENCY C.2. Enceinte: interpretation stratigraphique, reprise des travaux de Willett, datation C.3. Travail preparatoire a Sungbo’s Eredo: visite, prise de contacts et premier releve D. Analyses en cours D.1 Sedimentologie (Alain Person) D.2 Radiocarbon dating (Beta Analytics) D.3 Glass / material culture analysis OTHER SPONSORS AND PARTNERS 1 Table of Contents Executive summary ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 A. Partnerships and funding ......................................................................................................................... -

Effect of Oral Traditions, Folklores and History on the Development of Education in Nigeria, 1977 Till Date

History Research, Mar.-Apr., 2017, Vol. 7, No. 2, 59-72 doi 10.17265/2159-550X/2017.02.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Effect of Oral Traditions, Folklores and History on the Development of Education in Nigeria, 1977 Till Date Okediji, Hannah Adebola Aderonke Ministry of Education, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria Nigerian literatures contain history in the oral tradition and folklore like satire, proverbs, chants, symbolism etc. in the pre-literate period, Nigeria enjoyed high level of verbal art civilization which traditional rulers and the generality of the populace patronized. The oral tradition served as medium of preservation of culture and history of the ancient past and experiences. Though, most Nigerians can still remember their family history, folklore, tradition and genealogy, only few oral artists and youths of nowadays possess the skill and ability needed to chant the lengthy oral literature. It is in the light of the above that this study examined the effect of oral tradition, folklore, and history on the development of education in Nigeria, 1977 till date. The study adopted historical research method using primary and secondary sources of information to analyze data. Primary sources include, like archive materials, oral interviews and secondary sources include, like textbooks, speeches, journals, and internet materials and images. The outlines of the paper are: the definition of concepts, historical background of Nigerian oral tradition, and folklore in the educational system, the place of oral tradition, folklore and history in the education policy in Nigeria since 1977, the effect of oral tradition, folklore and history on the development of education in Nigeria since 1977, the prospects of oral traditions, folklore and history on the development of education in Nigeria, conclusion and a few recommendations for future improvement. -

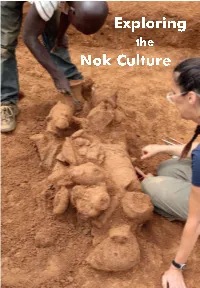

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture Joint Research Project of Goethe University Frankfurt/Main, Germany & National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria A publication of Goethe University, Institute for Archaeological Sciences, African Archaeology and Archaeobotany, Frankfurt/Main, Germany January 2017 Text by Peter Breunig Editing by Gabriele Franke & Annika Schmidt Translation by Peter Dahm Robertson Layout by Kirstin Brauneis-Fröhlich Cover Design by Gabriele Försterling Drawings by Monika Heckner & Barbara Voss Maps by Eyub F. Eyub Photos by Frankfurt Nok Project, Goethe University Printed by Goethe University Computer Center © 2017 Peter Breunig, Goethe University Project Funding Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) Partners Support A Successful Collaboration The NCMM and Goethe University continued their successful collaboration for field research on the Nok Culture Anyone interested in West Africa’s – and in central Nigeria. Starting in 2005, particularly Nigeria’s – prehistory will NCMM has ever since taken care of eventually hear about the Nok Culture. Its administrative matters and arranged artful burnt-clay (terracotta) sculptures the participation of their archaeological make it one of Africa’s best known experts which became valuable members ancient cultures. The Nok sculptures are of the project’s team. More recently, among the oldest in sub-Saharan Africa archaeologists from Ahmadu Bello and represent the origins of the West University in Zaria and Jos University African tradition of portraying people and joined the team. Together, the Nigerian animals. This brochure is a summary of and German archaeologists completed what we know about the Nok Culture and difficult work to gain information on this how we know what we know. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Illicit Traffic in Cultural Property in Nigeria: Aftermaths and Title Antidotes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Illicit Traffic in Cultural Property in Nigeria: Aftermaths and Title Antidotes Author(s) AKINADE, Olalekan Ajao AKINADE Citation African Study Monographs (1999), 20(2): 99-107 Issue Date 1999-06 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68183 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 20-2/2 03.4.3 9:49 AM ページ99 African Study Monographs, 20(2): 99-107, June 1999 99 ILLICIT TRAFFIC IN CULTURAL PROPERTY IN NIGERIA: AFTERMATHS AND ANTIDOTES Olalekan Ajao AKINADE National Museum, Nigeria ABSTRACT The concepts of national cultures and African cultures generated heated debate when scholarship was at its low ebb, thus promoting some scholars to argue against the existence of African culture. Today African reigns supreme in the art world, both ancient and contemporary, a result of the manifestations of the rich culture of Africa as a whole. In Nigeria, research and museum activities have exposed two thousand years of ancient art works of Nigeria, among other aspects of the rich cultures of the country. The ancient art works of Nigeria and her archaeological heritage have generated interest as well as interna- tional recognition. The rampant loss, theft, and pillage of cultural property in Nigeria is the central focus of this article. It looks at the immediate and remote causes of illicit traffic in cultural property. The article identifies some of the aftermaths of the nefarious activities, and proffers some solutions that may check them. Key Words: Illicit; Museum; Heritage; Nefarious; Traffic; Solutions.