The Restructuring of Ethnicity in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Socio – Cultural Rejuvenation: a Quest for Architectural Contribution in Kano Cultural Centres, Nigeria

International Journal of Advanced Academic Research | Social and Management Sciences | ISSN: 2488-9849 Vol. 5, Issue 3 (March 2019) SOCIO – CULTURAL REJUVENATION: A QUEST FOR ARCHITECTURAL CONTRIBUTION IN KANO CULTURAL CENTRES, NIGERIA Gali Kabir Umar1 and Danjuma Abdu Yusuf2 1&2Department of Architecture, Kano University of Science and Technology, P.M.B. 3244, Wudil, Kano State, Nigeria *Corresponding Author‟s Email: [email protected] 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT For thousand years, Kano astound visitors with its pleasing landscape full with colorful dresses, leather and art works, commodities, city wall and gates, ponds, mud houses, horsemen, and festivals. However, an attempt has been made to create a theoretical link between human society on earth and culture of individual groups or tribes but none have been found successful, since these theories of cultural synthesis do not encourage creating a unique monument of cultural styles, nevertheless, they help at producing practical theories that will easily be applicable and useful to norms redevelopment and general standard. This study aims to revitalize a forum in a society for cultural expressions known as “Dandali” in Hausa villages and towns which now metamorphosed into the present day cultural centre in Kano and the country at large. The study focuses on the socio- cultural life of Hausa/Fulani which is dominated by various activities; the normal get together, commercial activities and cultural entertainment. It reveals the lack of efficient and functional culture centre in the state since its creation; to preserve traditional and cultural heritage so as not be relegated to the background and be swallowed by its foreign counter parts. -

Construing a Relationship Between Northwestern Nigeria Terracotta Sculptures and Those of Nok

CONSTRUING A RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN NORTHWESTERN NIGERIA TERRACOTTA SCULPTURES AND THOSE OF NOK BY M. O. HAMBOLU National Commission for Museums and Monuments ‐ Nigeria Map of sites mentioned in the presentation INTRODUCTION • Terracotta sculptures have been discovered from several culture areas of Nigeria the more prominent ones being Nok, Ife, Sokoto/Katsina (NW) and Calabar. • Based on the present state of our knowledge, Nok is the oldest, with the Northwestern terracotta sites being their near contemporaries. Terracotta sculptures from Calabar area are older than those of Ife. • In this presentation, because of the relative geographical contiguity and the chronological closeness between Nok and the Northwestern terracotta sculptures, an attempt is being made to compare the two sculptural traditions in terms of style, motifs, techniques of production, archaeological contexts, intra and inter site relationships and dates. • It is believed that this long‐term endeavour, would contribute towards an understanding of the nature of relationships among societies that flourished in the Nigerian region during the first millenium BC and first millenium AD. ACTIVITIES AND RESEARCH IN THE NOK CULTURE AREA • Terracotta sculptures from the Nok region have been brought to the limelight through three principal means, namely, accidental discoveries, archaeological excavations and illegal diggings. • In conducting this comparative analysis, we shall – though unfortunate – utilize all sources to enable us have large data to work with. • While the ongoing archaeological work by Breunig’s team is increasing our understanding of the Nok sculptures and the societies that produced them, we shall also utilize the work of Boullier who analyzed about a thousand terracotta sculptures that were looted out of Nigeria to understand their styles, techniques of production and motifs etc. -

The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari

The Nok Terracotta Sculptures of Pangwari Tanja M. Männel & Peter Breunig Abstract Résumé Since their discovery in the mid-20th century, the terracottas Depuis leur découverte au milieu du XXe siècle, les sculptures of the Nok Culture in Central Nigeria, which represent the de la culture Nok au Nigeria central sont connues, au-delà des earliest large-scale sculptural tradition in Sub-Saharan Af- spécialistes, comme la tradition la plus ancienne des sculptures rica, have attracted attention well beyond specialist circles. de grande taille de l’Afrique subsaharienne. Toutefois leur Their cultural context, however, remained virtually unknown contexte culturel resta inconnu pour longtemps, dû à l’absence due to the lack of scientifically recorded, meaningful find de situations de fouille pertinentes démontrées scientifiquement. conditions. Here we will describe an archaeological feature Ici nous décrivons une découverte, trouvée à Pangwari, lieu uncovered at the almost completely excavated Nok site of de découverte Nok, située dans le sud de l’état de Kaduna, qui Pangwari, a settlement site located in the South of Kaduna fourni des informations suffisantes montrant que des sculptures State, which provided sufficient information to conclude that en terre cuite ont été détruites délibérément et puis déposées, ce the terracotta sculptures had been deliberately destroyed qui, par conséquent, met en évidence exemplaire l’aspect rituel and then deposited, emphasising the ritual aspect of early de l’ancien art plastique africain. Auparavant, des observations African figurative art. similaires ont été faites sur d’autres sites de recherches. Similar observations were made at various other sites Or les sculptures en terre cuite découvertes à Pangwari we had examined previously. -

Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp

NYAME AKUMA No. 73 June 2010 NIGERIA in the production of abundant and beautiful clay figu- rines. Its enigmatic character was underlined by the Outline of a New Research Project lack of any known precursor or successors leaving on the Nok Culture of Central the Nok Culture as a flourishing but totally isolated Nigeria, West Africa phenomenon in the archaeological sequence of the region. Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp Another surprise was the discovery of iron- smelting furnaces in Nok contexts, and at that time Peter Breunig and Nicole Rupp amongst the earliest evidence of metallurgy in sub- Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main Saharan Africa (Fagg 1968; Tylecote 1975). The com- Institut für Archäologische bination of early iron and elaborated art – in our west- Wissenschaften ern understanding – demonstrated the potential of Grüneburgplatz 1 the Nok Culture with regard to metallurgical origins 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany and the emergence of complex societies. emails: [email protected], [email protected] However, no one continued with the work of Bernard Fagg. Instead of scientific exploration, the Nok Culture became a victim of illegal diggings and internationally operating art dealers. The result was Introduction the systematic destruction of numerous sites and an immense loss for science. Most Africanist archae- Textbooks on African archaeology and Afri- ologists are confronted with damage caused by un- can art consider the so-called Nok Culture of central authorized diggings for prehistoric art, but it appears Nigeria for its early sophisticated anthropomorphic as if Nok was hit the hardest. Based on the extent of and zoomorphic terracotta figurines (Figures 1 and damage at numerous sites that we have seen in Ni- 2), and usually they emphasize the absence of con- geria, and according to the reports of those who had textual information and thus their social and cultural been involved in the damage, many hundreds if not purpose (Garlake 2002; Phillipson 2005; Willett 2002). -

Nok Terra-Cotta Discourse

IJournals: International Journal of Social Relevance & Concern ISSN-2347-9698 Volume 4 Issue 9 September 2016 NOK TERRA-COTTA DISCOURSE: PERSPECTIVES OF THE CERAMIST AND THE SCULPTOR Henry Asante (MFA, Ph.D) SCULPTURE UNIT DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS AND DESIGN, UNIVERSITY OF PORT HAROCURT, PORT HAROCOURT, NIGERIA. [email protected] +2348056056977(08056056977) AND PETERS, EDEM E. (MFA, M. Ed, Ph.D) CERAMICS UNIT DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS AND DESIGN, UNIVERSITY OF PORT HARCOURT, PORT HARCOURT, NIGERIA. [email protected] [email protected] +2348023882338(08023882338) ABSTRACT This article recalls the memory of one of the most remarkable art traditions on the African continent that survived many years of practice in a material and technique which hitherto could have been attributed to sculpture but has lately attracted controversial argument between sculpture and ceramics over the area of production it belongs. The Nok terra-cotta art works comprised human and animal forms and were made by a people that existed in an area near the confluence of Niger and Benue Rivers in central Nigeria between 500 BC and 200 AD. These hundreds of existed art works are at the center of an intellectual discourse, seeking an answer to the question as to who made the art works, the sculptor or the ceramist. Evidence from scholars, availability of clay as material, production techniques and end use or the possibility of the figures been used as ritual objects are among the parameters used in the attempt to establish the actual area of production the figures situate. Key words: Nok, terra-cotta, sculpture, ceramics, production Introduction The ownership of the Nok terra Cotta head has become a controversial issue between ceramics and sculpture. -

Effect of Oral Traditions, Folklores and History on the Development of Education in Nigeria, 1977 Till Date

History Research, Mar.-Apr., 2017, Vol. 7, No. 2, 59-72 doi 10.17265/2159-550X/2017.02.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Effect of Oral Traditions, Folklores and History on the Development of Education in Nigeria, 1977 Till Date Okediji, Hannah Adebola Aderonke Ministry of Education, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria Nigerian literatures contain history in the oral tradition and folklore like satire, proverbs, chants, symbolism etc. in the pre-literate period, Nigeria enjoyed high level of verbal art civilization which traditional rulers and the generality of the populace patronized. The oral tradition served as medium of preservation of culture and history of the ancient past and experiences. Though, most Nigerians can still remember their family history, folklore, tradition and genealogy, only few oral artists and youths of nowadays possess the skill and ability needed to chant the lengthy oral literature. It is in the light of the above that this study examined the effect of oral tradition, folklore, and history on the development of education in Nigeria, 1977 till date. The study adopted historical research method using primary and secondary sources of information to analyze data. Primary sources include, like archive materials, oral interviews and secondary sources include, like textbooks, speeches, journals, and internet materials and images. The outlines of the paper are: the definition of concepts, historical background of Nigerian oral tradition, and folklore in the educational system, the place of oral tradition, folklore and history in the education policy in Nigeria since 1977, the effect of oral tradition, folklore and history on the development of education in Nigeria since 1977, the prospects of oral traditions, folklore and history on the development of education in Nigeria, conclusion and a few recommendations for future improvement. -

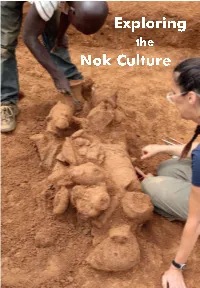

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture

Exploring the Nok Culture Exploring the Nok Culture Joint Research Project of Goethe University Frankfurt/Main, Germany & National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria A publication of Goethe University, Institute for Archaeological Sciences, African Archaeology and Archaeobotany, Frankfurt/Main, Germany January 2017 Text by Peter Breunig Editing by Gabriele Franke & Annika Schmidt Translation by Peter Dahm Robertson Layout by Kirstin Brauneis-Fröhlich Cover Design by Gabriele Försterling Drawings by Monika Heckner & Barbara Voss Maps by Eyub F. Eyub Photos by Frankfurt Nok Project, Goethe University Printed by Goethe University Computer Center © 2017 Peter Breunig, Goethe University Project Funding Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) Partners Support A Successful Collaboration The NCMM and Goethe University continued their successful collaboration for field research on the Nok Culture Anyone interested in West Africa’s – and in central Nigeria. Starting in 2005, particularly Nigeria’s – prehistory will NCMM has ever since taken care of eventually hear about the Nok Culture. Its administrative matters and arranged artful burnt-clay (terracotta) sculptures the participation of their archaeological make it one of Africa’s best known experts which became valuable members ancient cultures. The Nok sculptures are of the project’s team. More recently, among the oldest in sub-Saharan Africa archaeologists from Ahmadu Bello and represent the origins of the West University in Zaria and Jos University African tradition of portraying people and joined the team. Together, the Nigerian animals. This brochure is a summary of and German archaeologists completed what we know about the Nok Culture and difficult work to gain information on this how we know what we know. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Nigeria Case Study

This project is funded by the European Union November 2020 Culture in ruins The illegal trade in cultural property Case study: Nigeria Julia Stanyard and Rim Dhaouadi Summary This case study forms part of a set of publications on the illegal trade in cultural property across North and West Africa, made up of a research paper and three case studies (on Mali, Nigeria and North Africa). The research in this case study focuses on the Nok terracottas, the changing market for these artefacts and the regional trade routes. Attention is also given to the ambiguous role of the Artefact Rescuers Association of Nigeria (ARAN) in this trade. Key findings • Nok objects started being taken from Nigeria in the early 1980s. • In the late 1980s, several major thefts took place from museums and some were known to have been facilitated by museum staff. • The market peaked in the early 1990s and there is a decline in supply and demand for Nok objects at present. • Looting of Nok sites, however, continues and is driven by economic need, a lack of awareness of the laws surrounding antiquities, local communities not identifying with ancient cultural resources, and specific religious beliefs that archaeological sculptures need to be destroyed. • Looting has shifted from the northwest and north-central states to the southern part of the Nok region in response to rising insecurity and conflict. • Changes in demand for Nok objects are in some measure due to the increased value being placed on certifiable provenance of archaeological objects. CASE STUDY CASE • Local and regional intermediaries operating in urban hubs in Nigeria and neighbouring countries play a persistent and important role in the illegal market. -

Re-Inventing the Living Past from the Utilitarian Values of Pre-Historic Archaeology

Nkwocha, A. E. – Re-inventing the Living Past from the Utilitarian Values of Pre-Historic Archaeology: RE-INVENTING THE LIVING PAST FROM THE UTILITARIAN VALUES OF PRE-HISTORIC ARCHAEOLOGY: A CASE FOR INTER-DISCIPLINARY APPROACH NKWOCHA, ANTHONY E DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ALVAN IKOKU FEDERAL COLLEGE OF EDUCATION OWERRI IMO STATE Abstract This paper argues that the past material culture of any human society should always be subjected to criticisms and interpretive analysis based on archaeological evidence. It opines that in the interest of historical scholarship, certain inherent distortions that characterize oral and written histories should be re-evaluated, through the scientific research efforts of archaeology, to pave the way for more objective historical research. This paper submits that pre-historic archaeology can be very relevant to historical studies through its memorable artifacts which help the historian to dig deep into the dust heap of ancient cultures and civilization. Finally, this paper recommends that the archaeology curriculum should be overhauled to suit the needs of our eodern time while Ministries of CulturE afd Tourism at all levels of governmenp should exploit the rich heritage of ar#haeological sites like Nok, @aima, Ig`o-Ekwu, the styhistic terracotta of Ife and Benin Ivory mask cultures. Key Words: T`e living past histnry, Utilitarian values, PrE-history, Archaeology. Antroduction The ability of phe h)storian to reconstruct the past is always governed by tha evidence of past material cultere kf any group of people whether literate or pre-literate. Historians are in agreement that the past material celture of any human society should always be subjec4ed tm ariticises and ifterpretative analysis based mn tha canons of histgrical scholarship. -

Globalization, Cultural Heritage Management and the Sustainable Development Goals in Sub-Saharan Africa: the Case of Nigeria

heritage Article Globalization, Cultural Heritage Management and the Sustainable Development Goals in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Nigeria Caleb A. Folorunso Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Ibadan, Ibadan 200284, Nigeria; [email protected] Abstract: This paper addresses the impacts of globalization on cultural heritage conservation in sub-Saharan Africa. The homogenization and commodification of Indigenous cultures as a result of globalization and it’s impacts on the devaluation of heritage sites and cultural properties is discussed within a Nigerian context. Additionally, the ongoing global demand for African art objects continues to fuel the looting and destruction of archaeological and historical sites, negatively impacting the well- being of local communities and their relationships to their cultural heritage. Global organizations and institutions such as UNESCO, the World Bank, and other institutions have been important stakeholders in the protection of cultural heritage worldwide. This paper assesses the efficacy of the policies and interventions implemented by these organizations and institutions within Africa and makes suggestions on how to advance the protection of African cultural heritage within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Furthermore, cultural heritage conservation is explored as a core element of community well-being and a tool with which African nations may achieve Citation: Folorunso, C.A. Globalization, Cultural Heritage sustainable economic development. Management and