Camera Trapping in Southeast Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fredrikstad Kommune

127 FREDRIKSTAD KOMMUNE Fredrikstad kommune består, etter 1.1.1994, av kommunedelene Rolvsøy, Onsøy, Kråkerøy og Borge ved siden av Fredrikstad by. Fredrikstad storkommune grenser til Råde i nord, Sarpsborg i nord og øst og Hvaler i sør. Fredrikstad er i dag Norges sjette største bykommune med et 2 folketall på 65 ooo på et areal på 285 km • Byen ble grunnlagt ved Glommas munning av Fredrik II i 1567. Markerte festningsverk fra 1600-tallet gjorde Fredrikstad til landets sterkeste festning med 200 kanoner og 2000 manns besetning. Her lå hovedport for hær og flåte og Tordenskiolds operasjonsbase. Østfold regiment har fortsatt base i Gamlebyen (Statens kartverk 1994). Glomma ga adkomst til mange ulike industrier og en allsidig handelsvirksomhet. Byen har også rike tilbud innen kultur- og idrettsaktiviteter. Miljøverndepartementet har valgt Fredrikstad til en av fem norske miljøbyer. I Fredrikstad finnes flere nasjonale kulturverdier. Gamlebyen er Nordens best bevarte festningsby med renessansekvartaler, brolegginger lagt som tvangsarbeid, vollgraver og vindelbro. Et storstilt restaureringsarbeid ble ferdig i 1994. Dette inneholdt blant annet fjerning av mange store trær, både friske og døende. I kulturlandskapssammenheng med botaniske verdier som et formål, ble det således formodentlig ødelagt betydelige botaniske/biologiske verdier da restaureringsplanen ikke inkluderte hensyn til karplanteforekomster. Vollene ble slått årlig, og trærne ga stabil skygge. Mange av de verdifulle karplantene vi i dag hegner om, har sine nisjer i regelmessig hevdet slåttemark med stabile omgivelser. Det kan fortsatt finnes interessante karplanter i dette historiske miljø, men mye gikk trolig tapt under restaureringen. I alle fall gikk kunnskapen tapt om hva vollene inneholdt før restaureringen tok til da dette ble oversett eller bevisst forbigått. -

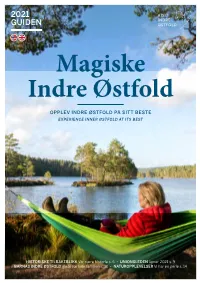

Magiske Indre Østfold OPPLEV INDRE ØSTFOLD PÅ SITT BESTE EXPERIENCE INNER ØSTFOLD at ITS BEST

2021 GUIDEN Magiske Indre Østfold OPPLEV INDRE ØSTFOLD PÅ SITT BESTE EXPERIENCE INNER ØSTFOLD AT ITS BEST HISTORISKE TILBAKEBLIKK Vår nære historie s. 6 • UNIONSLEDEN åpner 2021 s. 9 BARNAS INDRE ØSTFOLD glede for hele familien s. 10 • NATUROPPLEVELSER Vi har en perle s. 14 Velkommen til Indre Østfold Indre Østfold er uten tvil et sted for de gode opplevelsene. Et spennende grenseland mellom hovedstaden Oslo, i vest og Sverige i øst – både for deg som bor her, og for våre gjester fra fjern og nær. TA FOR DEG – VI HAR MYE Å TILBY! Foto: Fotograf Jonas Ingstad Last ned visitnorways app. – GRATIS! Planlegger du tur til Indre Østfold? Vi har inkludert vurderinger og omtaler fra På www.visitindre.no finner du info om Trip-Advisor på nettsiden vår. Her finner Få «hva skjer», restauranter, overnatting, museer, Hva skjer m.m. du nå råd og tips fra andre reisende. Tips overnatting etc. i nærheten Facebook: @visitindre andre om dine Indre Østfold-favoritter, slik av der du til enhver tid Instagram: @visit_indre_ostfold. at de kan få mest mulig ut av sitt besøk. befinner deg. 2 www.visitindre.no Om Indre Østfold .................................. 4-5 About Inner Østfold Historiske tilbakeblikk ......................... 6-8 Historical retrospective view Innhold Unionsleden .............................................. 9 Unionsleden Barnas Indre Østfold ......................... 10-11 Inner Østfold for children Jenteturer ........................................... 12-13 Ladies Tour Naturopplevelser .............................. 14-16 Nature Vandretips ................................................ 17 Hiking Tips Haldenkanalen .................................. 18-20 9 The Halden Canal Signalkreps .............................................. 21 UNIONSLEDEN Signal Crayfish Ny sykkeltrase Badeplasser ............................................. 22 fra Moss til Swimming Karlstad via Indre Østfold. Festivaler/arrangementer ............. 23-25 Foto: Tony Ryman Events and festivals Hva skjer ............................................ -

Konseptvalgutredning (Kvu) Vegforbindelser Øst for Oslo

11. MARS 2019 UTKAST KONSEPTVALGUTREDNING (KVU) VEGFORBINDELSER ØST FOR OSLO STATENS VEGVESEN REGION ØST Postboks 1010 Nordre Ål 2605 LILLEHAMMER FORORD Konseptvalgutredninger (KVU) skal kvalitetssikres i regi av Samferdselsdepartementet og Finansdepartementet av eksterne konsulenter. Dette kalles ekstern kvalitetssikring (KS1). Konseptvalgutredninger bygges opp i henhold til krav fra Finansdepartementet (Rammeavtale for kvalitetssikring av konseptvalg) i seks deler: - Behovsanalyse - Mål og strategidokument - Overordnet kravdokument - Mulighetsstudie - Alternativanalyse - Føringer for videre planlegging Kapittelinndelingen i denne konseptvalgutredningen bygger opp om disse seks hoveddokumentene slik: Finansdepartementets krav til Konseptvalgutredningens oppbygning struktur og struktur 1. Innledning 2. Situasjonsbeskrivelse Behovsanalyse 3. Behovsvurdering Mål og strategidokument 4. Mål og krav Overordnet kravdokument 5. Mulige løsninger Mulighetsstudie 6. Konsepter 7. Transportanalyse 8. Samfunnsøkonomisk analyse Alternativanalyse 9. Andre påvirkninger 10. Måloppnåelse Føringer for videre planlegging 11. Drøfting og anbefaling 12. Medvirkning og informasjon 13. Vedlegg, kilder og referanser 1 INNHOLD FORORD ........................................................................................................................................ 1 SAMMENDRAG ............................................................................................................................... 4 1 INNLEDNING .................................................................................................................. -

17/2020 - Innspill Om Prioriteringer På Transportområdet (Ref Sak 4/2020)

Sekretariat: Indre Østfold kommune [email protected] Rådhusgata 22, 1830 Askim Org. nr. 920 123 899 Sak: 17/2020 - Innspill om prioriteringer på transportområdet (ref Sak 4/2020) Indre Østfold regionråd beslutter følgende: Indre Østfold vil at følgende skal innarbeides i uttalelsen fra Viken fylkeskommune til Samferdselsdepartementet: 1. Prioritet 1: Ferdigstilling av ny avgreining Østfoldbanens Østre linje med dobbeltspor til Kråkstad stasjon og hensettingsanlegg Ski syd med ferdigstillelse senest 2026. Prioritet 2: Bygging av gjenstående parsell på E18 Retvet-Vinterbro og ferdigstilling møtefri E18 Lundeby-Ørje, senest 2025. Prioritet 3: Oppgradering av Rv 22 (som en del av ring 4 avlastning rundt Oslo), Fv 120 og fv 114/115. Prioritet 4: Bedre mobilitet- og kollektivløsninger i og mellom byer og tettsteder. Indre Østfold- kommuner bør bli pilot for bygdemiljøpakker for miljøvennlig transport og god mobilitet i distriktene. Prioritet 5: Vedlikehold av fylkesveier som er viktige for næringslivet. Prioritet 6: Utrede tiltak og markedspotensiale for gods- og persontrafikk på Østre linje. 2. Utredninger tilsier at et jernbaneprosjekt med reisetid Oslo -Stockholm via Ski på rett under 3 timer vil være bedriftsøkonomisk lønnsomt. Et slikt prosjekt vil dermed kunne finansieres av de reisende helt uavhengig av NTP. Øresundforbindelsen ble realisert på samme måte, hvilket viser at en slik modell fungerer i praksis. Med en reisetid på under 3 timer vil flytrafikk og personbilreiser på strekningen bli vesentlig redusert, med betydelige miljøeffekter. I tråd med høringsbrevets påpekning av behov for nytenking i hvordan man prioriterer prosjekter inn i NTP, samt behov for å nå klimamålene, bør det følgelig i forbindelse med NTP vurderes om Oslo-Stockholm kan realiseres som et separat prosjekt uavhengig av nasjonale transportplaner i de to land. -

Undersøkelser Av Naturområder I Østfold

Miljøvernavdelingen Østfold Undersøkelser av naturområder i Rapport 1/2017 Naturfaglige undersøkelser i Østfold XVII Serien Fylkesmannen i Østfold, rapport miljøvern Bestilling: Telefon 69 24 70 00. Postboks 325, 1502 Moss epost: [email protected] Miljøvernavdelingen er gjennom Fylkesmannen i Østfold underlagt Klima- og miljødepartementet og Miljødirektoratet. Fylkesmannen representerer den statlige miljøvernforvaltningen i fylket og er et viktig bindeledd mellom stat og kommune - og mellom offentlig myndighet og allmennheten. Miljøvernavdelingen hos fylkesmannen har følgende oppgaver: • Overvåking av forurensing: avfall, støy, avløp, utslipp til luft og vann • Tilsyn og kontroll med forurensende virksomheter • Forvaltning av vann og vassdrag • Vurdering av arealplaner (kommuneplaner, reguleringsplaner og andre arealsaker) • Vern og forvaltning av viktige naturområder, samt truede og sårbare arter • Vern og forvaltning av viktige vilt- og fiskeressurser • Sikre befolkningen adgang til friluftsliv Oversikt over rapportserien finnes på fylkesmannens hjemmeside, her ligger også rapportene tilgjengelig: http://www.fylkesmannen.no/Ostfold/Miljo-og- klima/Rapportserien/Miljovernavdelingens-rapportserie/ og i rapport nr.7, 2007: Rapporter gjennom 25 år, 1982 - 2007, en bibliografi. Oversikt over de siste års rapporter: 2/16 Undersøkelser av naturområder i Østfold. Naturfaglige undersøkelser XVI 1/16 Skjøtselsplan for Skårakilen naturreservat 4/15 Vannundersøkelser i Østfold. Naturfaglige undersøkelser XV. 3/15 20 år med el-fiske -

Innkalling Og Forslag Til Saksliste HO21-Rådsmøte 06.06.2018

Til HelseOmsorg21-rådet Direktør Camilla Stoltenberg, Folkehelseinstituttet (rådsleder) Dekan Björn Gustafsson, Det medisinske fakultet, NTNU (nestleder) Områdedirektør Anne Kjersti Fahlvik, Innovasjonsdivisjonen, Forskningsrådet Generalsekretær Anne Lise Ryel, Kreftforeningen Forskningsleder, professor Aud Obstfelder, NTNU Gjøvik Brukerrepresentant Cathrin Carlyle, Helse Nord RHF Direktør Christine Bergland, Direktoratet for e-helse Viseadministrerende direktør Clara Gram Gjesdal, Helse Bergen HF, Haukeland universitetssjukehus Daglig leder Dagfinn Bjørgen, KBT Midt-Norge Gründer og investor Eirik Næss-Ulseth Direktør for forskning, innovasjon og utdanning Erlend Smeland, OUS HF Førsteamanuensis Esperanza Diaz, Institutt for global helse og samfunnsmedisin, UiB Direktør næringsutvikling Fredrik Syversen, IKT Norge Dekan Gro Jamtvedt, Høgskole i Oslo og Akershus Instituttleder Guri Rørtveit, Institutt for global helse og samfunnsmedisin, UiB Leder Hilde Lurås, HØKH, Akershus universitetssykehus HF Administrerende direktør Håkon Haugli, Abelia Områdedirektør Inger Østensjø, KS Områdedirektør Jesper W. Simonsen, Samfunn og helse, Forskningsrådet Fylkestannlege/avdelingsleder Kari Strand, Nord-Trøndelag fylkeskommune Direktør Karita Bekkemellem, Legemiddelindustriens landsforening Direktør Kathrine Myhre, Norway Health Tech Områdedirektør Knut-Inge Klepp, Folkehelseinstituttet Leder Kåre Reiten, Levekårsstyret i Stavanger Generalsekretær Lilly Ann Elvestad, Funksjonshemmedes fellesorganisasjon Direktør Mona Skaret, Innovasjon Norge Kommunalsjef -

Aphanomyces Astaci 2018

Annual Report The surveillance programme for Aphanomyces astaci in Norway 2018 NORWEGIAN VETERINARY INSTITUTE The surveillance programme for Aphanomyces astaci in Norway 2018 Content Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 Aims ........................................................................................................................... 4 Materials and methods ..................................................................................................... 4 Work plan ................................................................................................................... 4 Surveillance sites .......................................................................................................... 4 eDNA monitoring ........................................................................................................... 6 Results and Discussion ...................................................................................................... 7 eDNA monitoring in the Halden watercourse .......................................................................... 7 eDNA monitoring in the Mosse watercourse ........................................................................... 8 eDNA monitoring in the Glomma watercourse ....................................................................... -

Kommuneplan for Fredrikstad Arealdelen 2020 - 2032

Foto:Walter Schøffthaler Kommuneplan for Fredrikstad arealdelen 2020 - 2032 Planforslag til annen gangs høring (rettet mars 2020) INNLEDNING .......................................................................................................................................... 33 Formålet med arealdelen .................................................................................................................. 33 Hovedgrep ......................................................................................................................................... 33 ET BÆREKRAFTIG FREDRIKSTAD ............................................................................................................ 44 Å leve i Fredrikstad ............................................................................................................................ 55 Å skape i Fredrikstad ......................................................................................................................... 88 Å møte framtiden i Fredrikstad ..................................................................................................... 1010 BYUTVIKLING ..................................................................................................................................... 1313 Fortettingsstrategien ..................................................................................................................... 1313 FMV‐vest ...................................................................................................................................... -

Aphanomyces Astaci 2019

Annual Report The surveillance programme for Aphanomyces astaci in Norway 2019 NORWEGIAN VETERINARY INSTITUTE The surveillance programme for Aphanomyces astaci in Norway 2019 Content Summary ........................................................................................................................2 Introduction ....................................................................................................................3 Aims ..............................................................................................................................4 Materials and methods ........................................................................................................5 Work plan ......................................................................................................................5 Surveillance sites .............................................................................................................5 eDNA monitoring .............................................................................................................7 Results and Discussion ........................................................................................................7 eDNA monitoring in the Halden watercourse ...........................................................................7 eDNA monitoring in the Mosse watercourse .............................................................................8 eDNA monitoring in the Glomma watercourse ..........................................................................8 -

Retningsvalg Indre Østfold

Mai 2015 CAND.OECON ØIVIND HOLT Retningsvalg Indre Østfold – 1 – – 2 – Innhold Forord . 4 1. Bakgrunn for utredningen . 5 2. Kommuneinndeling, bosetting, tettsteder, næring og arbeidsplasser . 6 2 .1 Historisk kommuneinndeling . 6 2 .2 Befolkningsutvikling . 6 2 .3 Senterstruktur . 8 2 .4 Kommunikasjon: Veg – jernbane . 10 2 .5 Andre administrative inndelinger og identitet . 10 2 .6 Forholdet til naboregionene . 13 2 .7 Arbeidsmarked, intern pendling og flytting . 13 2 .8 Sysselsetting . 14 2 .9 Den funksjonelle region . 15 3. Styring – tjenesteproduksjon – interkommunalt samarbeid . 17 3 .1 Politiske organisering . 17 3 .2 Myndighetsutøvelse . 18 3 .3 Kommunal økonomisk situasjon . 18 3 .5 Tjenesteproduksjon i regi av interkommunalt samarbeid . 21 4. Framtidige utfordringer . 24 4 .1 Regional vekst, tettstedsutvikling og jordvern . 24 4 .2 Et bedre tjenestetilbud . 26 4 .3 Nye kommunale oppgaver . 27 4 .4 Lokaldemokrati og stedsutvikling . 27 4 .5 Retningsvalg med et nytt kommunekart . 33 5. Ny kommunal inndeling . 38 5 .1 Inndeling - størrelse og framtidig vekst . 38 5 .2 En helhetlig samfunnsutvikling . 40 5 .3 Økonomi – kompetanse – medvirkning . 43 5 .4 Oppsummering . 45 – 3 – Forord Denne rapporten er en bestilling fra rådmennene i Indre Østfold . Formålet har vært å etablere et felles datagrunnlag og analyse av utviklingen i regionen . Rapporten skal være et underlag for den enkelte rådmanns saksbehandling i forbindelse med at kommunene skal foreta et retningsvalg når det gjelder framtidig kommuneinndeling, i løpet av våren . Antall foreslåtte alternativ skal redusere med sikte på å finne hvilke alternativ som er realistiske, og med hvilke andre kommuner det kan innledes forhandlinger . Oppdraget fra rådmennene dreide seg opprinnelig om å belyse alternativene en eller to kommuner i Indre Østfold . -

UA-Rapport 101/2018

Katrine Næss Kjørstad Øyvind Dalen Gunnar Berglund Rapport Marte Bakken Resell 101/2018 Utredning av kollektivtilbudet i Østfold Forord Fylkestinget i Østfold vedtok i sak 46/2015 økt satsing på kollektivtrafikk gjennom prosjektet "Østfold tar bussen". Et element i dette prosjektet var å gjennomgå hele kollektivtilbudet i Østfold. På oppdrag for Østfold fylkeskommune og Bypakke Nedre Glomma utarbeides forslag til et helhetlig kollektivtilbud i Østfold, som tar utgangspunkt i kundenes reisebehov slik de er i 2016, og slik reisebehovene forventes å være i et lengre perspektiv. Målsettingen er et mer effektivt og kundetilpasset kollektivtilbud. Prosjektet er to-delt: I første del ble det utarbeidet et forslag til rutetilbud i Nedre Glomma, som tar hensyn til utfordringene i byområdet. Dette arbeidet er dokumentert i UA-rapport 91/2017 Utredning av kollektivtilbudet i Nedre Glomma. I denne andre delen av prosjektet er det de resterende deler av Østfold som står i fokus. Prosjektet har bestått av flere deloppgaver som til sammen danner grunnlaget for forslag til nytt kollektivtilbud. Mange personer har såldes vært involvert i utredningsarbeidet. Prosjektet er et samarbeidsprosjekt mellom Urbanet Analyse og Asplan Viak. Katrine N. Kjørstad har vært prosjektleder og har gjennomført prosjektet sammen med Øyvind Dalen, Marte Bakken Resell og Gunnar Berglund, som har arbeidet med alt fra kartlegging, analyse og utarbeidelse av forlag til nytt tilbud. I tillegg har Mads Berg og Harald Høyem hatt ansvaret for modellkjøringer i RTM/UA-modellen, og Ingunn O. Ellis og Maria Amundsen har gjennomført og analysert markedsundersøkelsene. I tillegg har også andre medarbeidere bidratt med ulike innspill og beregninger. Bård Norheim har vært kvalitetssikrer. -

SARPSBORG KO:Ml\Tlune

475 SARPSBORG KO:Ml\tlUNE Sarpsborg kommune består, etter 1.1.1992, av kommunedelene Skjeberg, Tune og Varteig ved siden av Sarpsborg by. 2 Storkommunen har et areal på 407 km , og et folketall på 46 600 innbyggere. Sarpsborg grenser til Skiptvet i nord, Rakkestad og Halden i øst, Hvaler i sør og Fredrikstad, Råde og Våler i vest (Statens kartverk 1994). Sarpsborg er landets tredje eldste by grunnlagt av Olav den Hellige i 1016. På grunn av de gode livsvilkår langs Raet med nærhet til kysten, har distriktet vært befolket i over ti tusen år. I Sarpsborg finnes mange bautasteiner, gravhauger og gravrøyser, og ingen annen kommune har flere helleristnings felt i fylket enn Sarpsborg. I 1567 ble byen brent og ødelagt av svenskene. Folk flyttet sørover langs Glomma og grunnla Fredrikstad. Fossen i Sarpsborg ga imidlertid grunnlag for kraftkrevende industri, en virksomhet som tok fart i 1890-årene da Borregaard startet sin treforedlingsvirksomhet her. I løpet av 10 år ble bedriften landets største (Statens kartverk 1994). Fortsatt er Borregaard en kjemisk bedrift som gir arbeid til mange i Sarpsborgdistriktet. I 1760 ble Hafslund hovedgård anlagt nær fossen. Her drives fortsatt gårdsdrift, men som ved de fleste herregårder i fylket, er museal virksomhet vel så viktig. Etter sammenslåingen med de omkringliggende kommunene, er Sarpsborg blant de største byene i landet. Kommunen har 32 km2 ferskvann, 84 km2 dyrket mark og 229 km2 skog. Sarpsborg har også en av de største byparker i forhold til innbyggertallet, Kulåsparken. Parken utgjør et viktig rekreasjonsområde for byens befolkning samtidig som den gir rom for mange interessante virvelløse dyr.