Chapter-I Introduction Late Victorian Quest for Romance and High

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

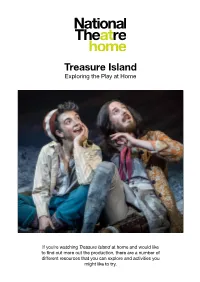

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home If you’re watching Treasure Island at home and would like to find out more out the production, there are a number of different resources that you can explore and activities you might like to try. About the Production Treasure Island was first performed at the National Theatre in 2014. The production was directed by Polly Findlay. Based on the 1883 novel by Robert Louis Stevenson, this stage production was adapted by Bryony Lavery. You can find full details of the cast and production team below: Cast Jim Hawkins: Patsy Ferran Grandma: Gillian Hanna Bill Bones: Aidan Kelly Dr Livesey: Alexandra Maher Squire Trelawny/Voice of the Parrot: Nick Fletcher Mrs Crossley: Alexandra Maher Red Ruth: Heather Dutton Job Anderson: Raj Bajaj Silent Sue: Lena Kaur Black Dog: Daniel Coonan Blind Pew: David Sterne Captain Smollett: Paul Dodds Long John Silver: Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey: Jonathan Livingstone Joan the Goat: Claire-Louise Cordwell Israel Hands: Angela de Castro Dick the Dandy: David Langham Killigrew the Kind: Alastair Parker George Badger: Oliver Birch Grey: Tim Samuels Ben Gunn: Joshua James Shanty Singer: Roger Wilson Parrot (Captain Flint): Ben Thompson Production team Director: Polly Findlay Adaptation: Bryony Lavery Designer: Lizzie Clachan Lighting Designer: Bruno Poet Composer: John Tams Fight Director: Bret Yount Movement Director: Jack Murphy Music and Sound Designer: Dan Jones Illusions: Chris Fisher Comedy Consultant: Clive Mendus Creative Associate: Carolina Valdés You might like to use the internet to research some of these artists to find out more about their careers. If you would like to find out about careers in the theatre, there’s lots of useful information on the Discover Creative Careers website. -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

TREASURE ISLAND Reimagined! Based on the Book by Robert Louis Stevenson SYNOPSIS

TREASURE ISLAND Reimagined! Based on the book by Robert Louis Stevenson SYNOPSIS Act I (50 minutes) Ahoy, Mateys! Join Jim Hawkins, Ben Gunn, Long John Silver, and the whole crew as they tell the classic story Treasure Island in an original and exciting version debuting at Dallas Children’s Theater! The play begins with Jim and Ben simultaneously telling their stories. Although their stories begin ten years apart, they were both deceived as young boys by the same scurvy pirate, Long John Silver. Year: 1871 Ben Gunn needs work after being abandoned by his father. He hears about a potential job working on Captain Flint’s pirate ship. Ben is dismayed when turned down by Flint, but soon meets Long John Silver who brings Ben on board Flint’s boat as the cabin boy. Year: 1881 Jim Hawkins and his friends are playing pirates when they are approached by an actual pirate, Billy Bones! Billy, protecting a chest he’s brought with him, tells the kids about Captain Flint’s lost treasure, the fifteen pirates who died burying it, and the pirate they need to beware of: the man with one-leg. When Jim’s mother approaches them, Billy asks for a room in the Hawkins’ inn. As she prepares his room, Billy warns Jim to look out for the one-legged man. That night, Jim has nightmares about a giant one-legged man. Year: 1871 Ben Gunn and Long John Silver sit together on the ship, looking at the stars. Long John tells Ben about the importance of constellations and the story of how proud Orion defeated every dangerous creature the gods sent his way until the gods sent a scorpion that killed Orion. -

Dutch Royal Family

Dutch Royal Family A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 08 Nov 2013 22:31:29 UTC Contents Articles Dutch monarchs family tree 1 Chalon-Arlay 6 Philibert of Chalon 8 Claudia of Chalon 9 Henry III of Nassau-Breda 10 René of Chalon 14 House of Nassau 16 Johann V of Nassau-Vianden-Dietz 34 William I, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg 35 Juliana of Stolberg 37 William the Silent 39 John VI, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg 53 Philip William, Prince of Orange 56 Maurice, Prince of Orange 58 Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange 63 Amalia of Solms-Braunfels 67 Ernest Casimir I, Count of Nassau-Dietz 70 William II, Prince of Orange 73 Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange 77 Charles I of England 80 Countess Albertine Agnes of Nassau 107 William Frederick, Prince of Nassau-Dietz 110 William III of England 114 Mary II of England 133 Henry Casimir II, Prince of Nassau-Dietz 143 John William III, Duke of Saxe-Eisenach 145 John William Friso, Prince of Orange 147 Landgravine Marie Louise of Hesse-Kassel 150 Princess Amalia of Nassau-Dietz 155 Frederick, Hereditary Prince of Baden-Durlach 158 William IV, Prince of Orange 159 Anne, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange 163 George II of Great Britain 167 Princess Carolina of Orange-Nassau 184 Charles Christian, Prince of Nassau-Weilburg 186 William V, Prince of Orange 188 Wilhelmina of Prussia, Princess of Orange 192 Princess Louise of Orange-Nassau 195 William I of the Netherlands -

The Analysis of Moral Ambiguity Seen Through

THE ANALYSIS OF MORAL AMBIGUITY SEEN IN LONG JOHN SILVER’S CHARACTERIZATION IN ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON’S TREASURE ISLAND AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degee of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By RONNY SANTOSO Student Number: 044214076 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2011 THE ANALYSIS OF MORAL AMBIGUITY SEEN IN LONG JOHN SILVER’S CHARACTERIZATION IN ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON’S TREASURE ISLAND AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degee of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By RONNY SANTOSO Student Number: 044214076 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2011 i ii iii . IF YOU LISTEN TO YOUR FEARS, YOU WILL DIE NEVER KNOWING WHAT A GREAT PERSON YOU MIGHT HAVE BEEN. Robert H. Schuller iv For My Beloved Family v LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIK Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma: Nama : RONNY SANTOSO Nomor Mahasiswa : 04 4214 076 Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul: THE ANALYSIS OF MORAL AMBIGUITY SEEN IN LONG JOHN SILVER’S CHARACTERIZATION IN ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON’S TREASURE ISLAND Beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, mengelolanya dalam bentuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikannya di Internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu meminta ijin ataupun memberikan royalti kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis. -

Treasure Island

Teacher’s Guide to The Core Classics Edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island By Alice R. Marshall Copyright 2003 Core Knowledge Foundation This online edition is provided as a free resource for the benefit of Core Knowledge teachers and others using the Core Classics edition of Treasure Island. Resale of these pages is strictly prohibited. Publisher’s Note We are happy to make available this Teacher’s Guide to the Core Classics version of Treasure Island prepared by Alice R. Marshall. We are presenting it and other guides in an electronic format so that they are accessible to as many teachers as possible. Core Knowledge does not endorse any one method of teaching a text; in fact we encourage the creativity involved in a diversity of approaches. At the same time, we want to help teachers share ideas about what works in the classroom. In this spirit we invite you to use any or all of the ways Alice Marshall has found to make this book enjoyable and understandable to fourth grade students. Her introductory material concentrates on using Treasure Island as a way of teaching students some valuable lessons about style, about how to make their own writing more lively and more powerful. This material is favored over the comprehensive biographical information presented in some of the other guides. For those who want more information than is presented in the brief biography in the back of the Core Classics edition, the author has cited a very good web site in her bibliography. There you will find much more material than you will ever have time to use. -

CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS Season 4 CAPTAIN FLINT

CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS Season 4 CAPTAIN FLINT (Toby Stephens) A former Naval officer, disgraced and betrayed, Captain Flint now leads an alliance of pirates and slaves intent on overthrowing the New World. ELEANOR GUTHRIE (Hannah New) A target for anger and suspicion following the death of Charles Vane, Eleanor Guthrie now sits behind the throne, in deference to Woodes Rogers. But as his war with the pirates threatens to consume him entirely, she will once again face an impossible choice, if there is to be any hope for their future. JOHN SILVER (Luke Arnold) Once an outcast, now the stuff of legend, thanks to the propagandist talents of Billy Bones. But as the costs of Flint’s war continue to mount, Silver must decide once and for all if he intends to assume the mantle of Pirate King… or bury it in the ground forever. MAX (Jessica Parker Kennedy) A former prostitute, now a key player in Woodes Rogers’ plan to quell the pirate threat. But can she bring peace to Nassau before the perils of war and ideology consume them all? BILLY BONES (Tom Hopper) Once the boatswain on Flint’s ship, now the leader of the pirate resistance on Nassau. But holding his own against Rogers’ redcoat allies has taken its toll… and given Billy a taste of authority he may not be so ready to relinquish. JACK RACKHAM (Toby Schmitz) Rescued from certain death, now intent on repaying the favor, Rackham teams with Edward Teach to bring Charles Vanes’ executioners to account. But when Woodes Rogers’ regime proves more resilient than believed, Rackham is forced to put everything on the table… his life, his loves, and his legacy… if he hopes to one day balance the scales. -

Odds on Treasure Island William H

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 5 1996 Odds on Treasure Island William H. Hardesty III. David D. Mann Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hardesty, William H. III. and Mann, David D. (1996) "Odds on Treasure Island," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 29: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol29/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William H Hardesty, III David D. Mann Odds on Treasure Island Knowledge of a writer's life can often help readers glimpse how that writer crafted fictional worlds. Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island (1883) is a case in point. 1 Because Treasure Island is an imaginative work of fiction specifically designed for younger readers, contemporary audiences seldom see the relevance of Stevenson's life to the novel they read. Yet an examination of what Stevenson was doing in 1881, when he wrote the original narrative, provides us with some understanding of how it was written and why Stevenson used certain fictive elements in the fabric of the nove1. 2 Knowing that Stevenson wrote part of the novel in Scotland and part in Switzerland-with a long interruption between the efforts-forces us to consider the differences between these two parts. Stevenson began the novel in late August 1881, basing the setting on a map he had drawn to entertain his stepson (Samuel) Lloyd Osbourne (the S. -

Treasure Island the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Treasure Island The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: J. Todd Adams (left) as Ben Gunn and Sceri Sioux Ivers as Jim Hawkins in the Utah Shakespeare Festival’s 2017 production of Treasure Island. Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 CharactersTreasure Island 5 Playwrights 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play A Recipe for Gleeful Romance 9 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: Treasure Island Mrs. Hawkins runs the Admiral Benbow Inn where Captain Billy Bones comes to stay, hiding from a “seafarin’ man with one leg.” The townspeople flock to hear his stories, though Dr. -

Black Sails Rainbow Flag Examining Queer Representations in Film And

Black Sails, Rainbow Flag: Examining Queer Representations in Film and Television Diana Cristina Răzman Media and Communication Studies Culture, Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries Master’s Thesis (One-year), 15 ECTS VT 2020 Supervisor: Temi Odumosu Abstract This thesis aims to present, discuss, and analyze issues relating to queer representations in film and television. The thesis focuses on existing tropes, such as queer coding, queerbaiting, and the “Bury Your Gays” trope that are prevalent in contemporary media, and applies the analysis of these tropes to a case study based on the television series Black Sails (2014-2017). The study forms its theoretical framework from representation theory and queer theory and employs critical discourse analysis and visual analysis as methods of examining the television series. The analysis explores the main research question: in what way does Black Sails subvert or reproduce existing queer tropes in film and television? This then leads to the discussion of three aspects: the way queer sexual identities are represented overall, what representational strategies are employed by the series in a number of episodes, and whether or not these representations reproduce or subvert media tropes. The results show that the series provides balanced and at times innovative representations of queer identity which can signal a change in the way LGBTQ themes and characters are represented in media. Keywords: Black Sails, queer representation, LGBT characters, media studies, queer studies, media representations, Captain Flint, John Silver. Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 2. Social and historical contexts .................................................................................. 5 2.1. LGBTQ themes in American mainstream media ........................................... -

Treasure Island

Treasure Island This text is based on Chapter 12 of the book ‘Treasure Island’. Jim Hawkins is a young boy who finds an old pirate’s treasure map. He sets off with a ship and a crew to find the treasure. On the ship, he overhears that Long John Silver is planning to take all of the treasure for himself. Jim is about to tell the captain when someone shouts that they can see an island ahead. The crew gathered on the deck and pointed at the island. “Have any of you ever seen that land before?” asked the captain. “I have, sir,” replied Long John Silver. “I’ve visited it before when I was working on another ship.” “Can you remember anything about it?” said the captain while looking into a telescope. Silver nodded, “It used to be visited by lots of pirates. They called it Skeleton Island.” He continued, “You see that hill there? They called that Spy-Glass because it’s where they looked out for other ships.” The crew looked and saw a huge hill that was covered by clouds. Captain Smollett pulled something from his pocket and opened it up. Silver recognised it as a map of the island and felt a rush of excitement. However, he felt disappointed when he couldn’t see a big, red cross. This wasn’t the treasure map that he was looking for. “This is a very detailed map,” he said slowly. “Pirates definitely didn’t make this.” Silver pointed at the edge of the map, “There it is. -

Download Download

The Piratical Counterfactual from Misson to Melodrama (summary) MANUSHAG N. POWELL Pirate lore, particularly the melodramatic form that dominated in the nineteenth century and re- mains very much in circulation today, would simply not function without authors and audiences alike having inherited a tradition of counterfactual thinking. The aim of this essay is to suggest (using pirates both real and imagined as the case in point) that by the eighteenth century, coun- terfactual writing was already in place and ready to contribute to the romantic aesthetic. Eighteenth-century pirate writing liked to speculate about pirate colonies and utopias, and while there is nothing especially romantic about utopian thinking in general, the specific case of a pirate paradise brings an air of counterculture freedom that resonates well with the yearnings for liberté, égalité, fraternité still to come. That pirates held appeal for nineteenth-century audi- ences is not very shocking, for they represented rebellion, class warfare, the troubles of empire, and the sort of magnetic, misanthropic antihero often termed “Byronic.” But eighteenth- and nineteenth-century pirates are linked generically as well as thematically. It is not far wrong to consider nearly all latter-day literary pirates as what some literary schol- ars call “counterfictions,” deliberate revisions of established literary worlds to improve, correct, or wonder “what if?”—for example, something like Nahum Tate’s famous happy-ending version of King Lear, or J. M. Barrie’s Captain Hook, who served with Blackbeard (real) and frightened Captain Flint (fictional).1 Before they could be fictionalized and counterfictionalized, real pirates were adapted, counterfactualized, and the blank spaces in their autobiographies filled (their dimmer character aspects made more brilliant).