Diplomarbeit / Diploma Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Playful Subversions: Hollywood Pirates Plunder Spanish America NINA GERASSI-NAVARRO

Playful Subversions: Hollywood Pirates Plunder Spanish America NINA GERASSI-NAVARRO The figure of the pirate evokes a number of distinct and contrasting images: from a fearless daredevil seeking adventure on the high seas to a dangerous and cruel plunderer moved by greed. Owing obedience to no one and loyal only to those sharing his way of life, the pirate knows no limits other than the sea and respects no laws other than his own. His portrait is both fascinating and frightening. As a hero, he is independent, audacious, intrepid and rebellious. Defying society's rules and authority, sailing off to the unknown in search of treasures, fearing nothing, the pirate is the ultimate symbol of freedom. But he is also a dangerous outlaw, known for his violent tactics and ruthless assaults. The social code he lives by inspires enormous fear, for it is extremely rigid and anyone daring to disobey the rules will suffer severe punishments. These polarized images have captured the imagination of historians and fiction writers alike. Sword in hand, eye-patch, with a hyperbolic mustache and lascivious smile, Captain Hook is perhaps the most obvious image-though burlesque- of the dangerous fictional pirate. His greedy hook destroys everything that crosses his hungry path, even children. On a more serious level, we might think of the tortures the cruel and violent Captain Morgan inflicted upon his enemies, hanging them by their testicles, cutting their ears or tongues off; or of Jean David Nau, the French pirate known as L 'Ollonais (el Olonés in Spanish), who would rip the heart out of his victims if they did not comply with his requests; 1 or even the terrible Blackbeard who enjoyed locking himself up with a few of his men and shooting at them in the dark: «If I don't kill someone every two or three days I will lose their respect» he is said to have claimed justifyingly. -

William Hope Hodgson's Borderlands

William Hope Hodgson’s borderlands: monstrosity, other worlds, and the future at the fin de siècle Emily Ruth Alder A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 © Emily Alder 2009 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter One. Hodgson’s life and career 13 Chapter Two. Hodgson, the Gothic, and the Victorian fin de siècle: literary 43 and cultural contexts Chapter Three. ‘The borderland of some unthought of region’: The House 78 on the Borderland, The Night Land, spiritualism, the occult, and other worlds Chapter Four. Spectre shallops and living shadows: The Ghost Pirates, 113 other states of existence, and legends of the phantom ship Chapter Five. Evolving monsters: conditions of monstrosity in The Night 146 Land and The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’ Chapter Six. Living beyond the end: entropy, evolution, and the death of 191 the sun in The House on the Borderland and The Night Land Chapter Seven. Borderlands of the future: physical and spiritual menace and 224 promise in The Night Land Conclusion 267 Appendices Appendix 1: Hodgson’s early short story publications in the popular press 273 Appendix 2: Selected list of major book editions 279 Appendix 3: Chronology of Hodgson’s life 280 Appendix 4: Suggested map of the Night Land 281 List of works cited 282 © Emily Alder 2009 2 Acknowledgements I sincerely wish to thank Dr Linda Dryden, a constant source of encouragement, knowledge and expertise, for her belief and guidance and for luring me into postgraduate research in the first place. -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Lundy Supplement 2018 Paul Harrison

Lundy Supplement 2018 Paul Harrison Climbers’ Club Guides Contents Lundy Supplement 2018 Introduction 3 Silver Slabs 14 by Paul Harrison The Pyramid Cliff 15 The South Coast 4 artwork by Simon Cardy Damocles Buttress 4 Beaufort Buttress Area 15 Kistvaen Buttress 4 Picnic Bay Cliff 15 edited, typeset, and The Devil’s Limekiln Area 4 Wonderland 18 prepared for web Hidden Zawn 4 Dihedral Slabs 19 publication by John The Devil’s Limekiln 5 Freak Zawn 20 Willson Nine-Digit Zawn 5 Beaufort Buttress 20 cover photo: Focal Buttress 6 Grand Falls Zawn Area 21 Cryptic Groove Focal Tower 6 Grand Falls Zawn 21 (Atlantic Buttress, E1, FA) Leaning Buttress 6 The Parthenos 21 P Harrison Montagu Steps Area 7 Threequarter Wall Area 22 Weird Wall 7 Black Bottom Buttress 22 adjacent photo: Montagu Buttress 7 Threequarter Buttress 22 The Prisoner (The Devil’s Les Aguilles du Montagu 7 Lady Denise’s Buttress 22 Limekiln, XS, FA) Goat Island 8 Ten Foot Zawn 22 Goat Crag 8 Devil’s Slide Area 23 Pilots’ Quay Area 8 St James’s Stone 23 Introduction Atlantic Buttress 8 Starship Zawn 23 Pilots’ Quay 9 Squires View Zawn 24 Since the publication of the 2008 guide, the island has seen a steady flow of new climbs as Trawlerman’s Buttress 9 Squires View Cliff 24 well as a number of significant repeats. This supplement records all this activity, along with The Blob 10 The Fortress 24 any information regarding known rockfalls and some minor corrections to the guide. Old Light Area 10 Torrey Canyon Bay 24 Routes that are not known to have had a second ascent are marked with the usual †, Sunset Wall 10 Torrey Canyon Cliff 24 and any stars proposed for them are left hollow. -

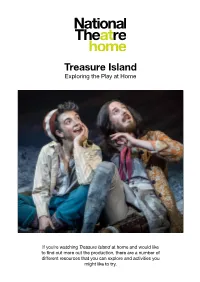

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home If you’re watching Treasure Island at home and would like to find out more out the production, there are a number of different resources that you can explore and activities you might like to try. About the Production Treasure Island was first performed at the National Theatre in 2014. The production was directed by Polly Findlay. Based on the 1883 novel by Robert Louis Stevenson, this stage production was adapted by Bryony Lavery. You can find full details of the cast and production team below: Cast Jim Hawkins: Patsy Ferran Grandma: Gillian Hanna Bill Bones: Aidan Kelly Dr Livesey: Alexandra Maher Squire Trelawny/Voice of the Parrot: Nick Fletcher Mrs Crossley: Alexandra Maher Red Ruth: Heather Dutton Job Anderson: Raj Bajaj Silent Sue: Lena Kaur Black Dog: Daniel Coonan Blind Pew: David Sterne Captain Smollett: Paul Dodds Long John Silver: Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey: Jonathan Livingstone Joan the Goat: Claire-Louise Cordwell Israel Hands: Angela de Castro Dick the Dandy: David Langham Killigrew the Kind: Alastair Parker George Badger: Oliver Birch Grey: Tim Samuels Ben Gunn: Joshua James Shanty Singer: Roger Wilson Parrot (Captain Flint): Ben Thompson Production team Director: Polly Findlay Adaptation: Bryony Lavery Designer: Lizzie Clachan Lighting Designer: Bruno Poet Composer: John Tams Fight Director: Bret Yount Movement Director: Jack Murphy Music and Sound Designer: Dan Jones Illusions: Chris Fisher Comedy Consultant: Clive Mendus Creative Associate: Carolina Valdés You might like to use the internet to research some of these artists to find out more about their careers. If you would like to find out about careers in the theatre, there’s lots of useful information on the Discover Creative Careers website. -

Captain Hook by Shel Silverstein

Captain Hook By Shel Silverstein Read the poem and the drama and then answer the questions. Captain Hook Captain Hook must remember Not to scratch his toes. Captain Hook must watch out And never pick his nose. Captain Hook must be gentle When he shakes your hand. Captain hook must be careful Openin’ sardine cans And playing tag and pouring tea and turnin’ pages of this book. Lots of folks I’m glad I ain’t— But mostly Captain Hook! Drama: CAPTAIN HOOK: Shiver me timbers, Smee! I can’t sleep. I can’t eat. I won’t rest until I find Peter Pan. Just look what he did to me! (Holds up arm with hook.) SMEE: A terrible, terrible thing, Captain. Chopping off your arm! CAPTAIN HOOK: And feeding it to a crocodile. That slithering reptile likes the taste of me! He follows me wherever I go just hoping to get a nibble! (Move up in front of curtain. Close curtain. Lost Boys set up.) [CAPTAIN HOOK sings a song] SMEE: Terrible, terrible! Thank heaven the beast swallowed a clock! CAPTAIN HOOK: That’s the only thing that keeps me alive, Smee. Soon it will wind down and you know what that means. (Uses his finger for tick-tock.) Tick. Tock. Tick. Tock. Tick… (Finger is stuck.) No tock! SMEE: Oh, terrible, terrible! Wait! What’s that I hear ***SOUND CUE Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick- tock… ****Crocodile Sound? CROCODILE enters from behind the audience and slithers up the aisle toward CAPTAIN HOOK. Sound cue continue tick-tocking until CROCODILE exits.) CAPTAIN HOOK: Blame it all on PETER PAN!!! (Runs, exiting.) 1. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Reading and activity ideas for your Chatterbooks group About this pack Ahoy, me Hearties – and shiver me timbers! Here be a Chatterbooks pack full of swashbuckling pirate fun – activity ideas and challenges, and great reading for your group! The pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their publisher partnership Children’s Reading Partners Chatterbooks [ www.readinggroups.org/chatterbooks] is a reading group programme for children aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. The Reading Agency is an independent charity working to inspire more people to read more through programmes for adults, young people and Children – including the Summer Reading Challenge, and Chatterbooks. See www.readingagency.org.uk Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Contents 2 Things to talk about 2 Activity ideas 8 Chatterbooks double session plan, with a pirates theme 10 Pirates and perils quiz 11 Pirates and perils: great titles to read 17 More swashbuckling stories For help in planning your Chatterbooks meeting, have a look at these Top Tips for a Successful Session 2 Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Ideas for your Chatterbooks sessions Things to talk about What do you know about pirates? Get together a collection of pirate books – stories and non-fiction – so you’ve got lots to refer to, and plenty of reading for your group to share. -

AYREAU M Story on Page 22 CHRISTINE GOOCH JULY 2014 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 DEPARTMENTS Info & Updates

C A R I B B E A N On-line C MPASS JULY 2014 NO. 226 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore AGNETIC AYREAU M Story on page 22 CHRISTINE GOOCH JULY 2014 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 DEPARTMENTS Info & Updates ......................4 The Caribbean Sky ...............34 Business Briefs .......................7 Cooking with Cruisers ..........38 Eco-News .............................. 9 Readers’ Forum .....................39 Regatta News........................ 11 Calendar of Events ...............40 All Ashore… .......................... 22 Product Postings ...................40 Fun Page ............................... 30 What’s On My Mind ..............41 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore Meridian Passage .................31 Caribbean Market Place .....42 Book Reviews...................31, 32 Classified Ads ....................... 46 www.caribbeancompass.com Movie Review ....................... 33 Advertisers’ Index .................46 JULY 2014 • NUMBER 226 Caribbean Compass is published monthly by Compass Publishing Ltd., P.O. Box 175 BQ, Bequia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines. BOYAN ULTRA Tel: (784) 457-3409, Fax: (784) 457-3410 [email protected] Guna Yala Rules www.caribbeancompass.com Tips for the San Blas bound .. 18 Editor...........................................Sally Erdle [email protected] HOGAN Assistant Editor...................Elaine Ollivierre Martinique: Ad Sales & Distribution - Isabelle Prado [email protected] Tel: (0596) 596 68 69 71 Mob: + 596 696 74 77 01 [email protected] Advertising -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

Boats Fact Sheets 3

Name That Boat! A boat’s name can tell a lot about its owner, for example their life philosophy, passions or who their loved ones are. They often also contain a funny pun. Here are some fun pun names of boats already out there: Boaty McBoatface (named after a public poll) Current-Sea Usain Boat (named after the fastest man in the world, Usain Bolt) Knot Shore Above: After a public poll voted to have this boat The Codfather named Boaty McBoatface, the owners thought it Vitamin Sea was too silly and it has since been renamed HMS Sea Ya David Attenborough Many boat names also come from classic books, lms and television. Here are some: Sirius and The Unicorn are just two of the boats in The Adventures of Tin-Tin books by Herge that often had lots of nautical adventure. Wonkatania transports the children through the factory on an exhilarating ride in Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Jolly Roger was the name of Captain Hook’s ship in the Peter Pan stories by JM Barrie. Swallow and Amazon are the names of the two sailing dinghies featured in the Swallow’s and Amazon’s adventure series by Arthur Ransome. The Mongolia and The Henrietta are just two of the steamer ships featured in Around the World in 80 days, Jules Verne classic novel where Phileas Fogg and assistant Passepartout set out to circumnavigate the globe in order to win a bet. The Dawn Treader from the classic children’s series the Chronicles of Narnia by CS Lewis.