Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin Mcdonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz

‘A Man of Courage and Activity’: Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin McDonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz “The sea is everything it is said to be: it provides unity, transport , the means of exchange and intercourse, if man is prepared to make an effort and pay a price.” – Fernand Braudel In the summer of 1694, Thomas Tew, an infamous Anglo -American pirate, was observed riding comfortably in the open coach of New York’s only six -horse carriage with Benjamin Fletcher, the colonel -governor of the colony. 2 Throughout the far -flung English empire, especially during the seventeenth century, associations between colonial administrators and pirates were de rig ueur, and in this regard , New York was similar to many of her sister colonies. In the developing Atlantic world, pirates were often commissioned as privateers and functioned both as a first line of defense against seaborne attack from imperial foes and as essential economic contributors in the oft -depressed colonies. In the latter half of the seventeenth century, moreover, colonial pirates and privateers became important transcultural brokers in the Indian Ocean region, spanning the globe to form an Indo-Atlantic trade network be tween North America and Madagascar. More than mere “pirates,” as they have traditionally been designated, these were early modern transcultural frontiersmen: in the process of shifting their theater of operations from the Caribbean to the rich trading grounds of the Indian Ocean world, 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the “Counter -Currents and Mainstreams in World History” conference at UCLA on December 6-7, 2003, organized by Richard von Glahn for the World History Workshop, a University of California Multi -Campus Research Unit. -

Making a Digital Critical Edition of Captain Charles

Digitizing the Pyrates: Making a Digital Critical Edition of Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates (1724-1726) by Ingrid Reiche A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Collaborative Program in the Digital Humanities and English Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016, Ingrid Reiche Reiche ii Abstract Critical editing in a digital environment has changed how bibliographic practices are employed. This thesis investigates how digital critical editing impacts eighteenth- century literary studies. The way scholars examine questions of author attribution and employ bibliography practices has changed with the advent of digital tools. Since the mid nineteen-nineties, digital editing has taken on various forms, from hypermedia archives to crowdsourced projects. A critical apparatus that provides a high-level of interactivity to elucidate the intricacies of a text over its production in a given time is often overlooked in these projects. By producing a digital edition that compares the first four editions of A General History of the Pyrates (1724-26) using the Versioning Machine V.4.0 and conducting a user experience survey regarding the edition’s functionality (both are at http://ingridreiche.com/Resume/Thesis.html), the goal of this project has been to show how eighteenth-century print culture was a highly collaborative space where authorship was unstable. Reiche iii Acknowledgments Dedicated to Eric and Mary Ann Reiche for all their encouragement, support, hours of reading and helping to iron out my ideas. With special thanks to Professor Brian Greenspan for his editorial diligence, insight and patience, and for motivating me to always look beyond my original goals. -

Playful Subversions: Hollywood Pirates Plunder Spanish America NINA GERASSI-NAVARRO

Playful Subversions: Hollywood Pirates Plunder Spanish America NINA GERASSI-NAVARRO The figure of the pirate evokes a number of distinct and contrasting images: from a fearless daredevil seeking adventure on the high seas to a dangerous and cruel plunderer moved by greed. Owing obedience to no one and loyal only to those sharing his way of life, the pirate knows no limits other than the sea and respects no laws other than his own. His portrait is both fascinating and frightening. As a hero, he is independent, audacious, intrepid and rebellious. Defying society's rules and authority, sailing off to the unknown in search of treasures, fearing nothing, the pirate is the ultimate symbol of freedom. But he is also a dangerous outlaw, known for his violent tactics and ruthless assaults. The social code he lives by inspires enormous fear, for it is extremely rigid and anyone daring to disobey the rules will suffer severe punishments. These polarized images have captured the imagination of historians and fiction writers alike. Sword in hand, eye-patch, with a hyperbolic mustache and lascivious smile, Captain Hook is perhaps the most obvious image-though burlesque- of the dangerous fictional pirate. His greedy hook destroys everything that crosses his hungry path, even children. On a more serious level, we might think of the tortures the cruel and violent Captain Morgan inflicted upon his enemies, hanging them by their testicles, cutting their ears or tongues off; or of Jean David Nau, the French pirate known as L 'Ollonais (el Olonés in Spanish), who would rip the heart out of his victims if they did not comply with his requests; 1 or even the terrible Blackbeard who enjoyed locking himself up with a few of his men and shooting at them in the dark: «If I don't kill someone every two or three days I will lose their respect» he is said to have claimed justifyingly. -

PIRATES Ssfix.Qxd

E IFF RE D N 52 T DISCOVERDISCOVER FAMOUS PIRATES B P LAC P A KBEARD A IIRRAATT Edward Teach, E E ♠ E F R better known as Top Quality PlayingPlaying CardsCards IF E ♠ SS N Plastic Coated D Blackbeard, was T one of the most feared and famous 52 pirates that operated Superior Print along the Caribbean and A Quality PIR Atlantic coasts from ATE TR 1717-18. Blackbeard ♦ EAS was most infamous for U RE his frightening appear- ance. He was huge man with wild bloodshot eyes, and a mass of tangled A hair and beard that was twisted into dreadlocks, black ribbons. In battle, he made himself andeven thenmore boundfearsome with by ♦ wearing smoldering cannon fuses stuffed under his hat, creating black smoke wafting about his head. During raids, Blackbeard car- ried his cutlass between his teeth as he scaled the side of a The lure of treasure was the driving force behind all the ship. He was hunted down by a British Navy crew risks taken by Pirates. It was ♠ at Ocracoke Inlet in 1718. possible to acquire more booty Blackbeard fought a furious battle, and was slain ♠ in a single raid than a man or jewelry. It was small, light, only after receiving over 20 cutlass wounds, and could earn in a lifetime of regu- and easy to carry and was A five pistol shots. lar work. In 1693, Thomas widely accepted as currency. A Tew once plundered a ship in Other spoils were more WALKING THE PLANK the Indian Ocean where each practical: tobacco, weapons, food, alco- member received 3000 hol, and the all important doc- K K ♦ English pounds, equal to tor’s medical chest. -

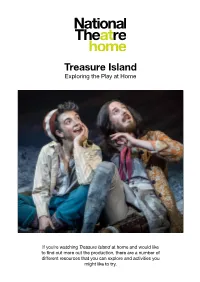

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home

Treasure Island Exploring the Play at Home If you’re watching Treasure Island at home and would like to find out more out the production, there are a number of different resources that you can explore and activities you might like to try. About the Production Treasure Island was first performed at the National Theatre in 2014. The production was directed by Polly Findlay. Based on the 1883 novel by Robert Louis Stevenson, this stage production was adapted by Bryony Lavery. You can find full details of the cast and production team below: Cast Jim Hawkins: Patsy Ferran Grandma: Gillian Hanna Bill Bones: Aidan Kelly Dr Livesey: Alexandra Maher Squire Trelawny/Voice of the Parrot: Nick Fletcher Mrs Crossley: Alexandra Maher Red Ruth: Heather Dutton Job Anderson: Raj Bajaj Silent Sue: Lena Kaur Black Dog: Daniel Coonan Blind Pew: David Sterne Captain Smollett: Paul Dodds Long John Silver: Arthur Darvill Lucky Mickey: Jonathan Livingstone Joan the Goat: Claire-Louise Cordwell Israel Hands: Angela de Castro Dick the Dandy: David Langham Killigrew the Kind: Alastair Parker George Badger: Oliver Birch Grey: Tim Samuels Ben Gunn: Joshua James Shanty Singer: Roger Wilson Parrot (Captain Flint): Ben Thompson Production team Director: Polly Findlay Adaptation: Bryony Lavery Designer: Lizzie Clachan Lighting Designer: Bruno Poet Composer: John Tams Fight Director: Bret Yount Movement Director: Jack Murphy Music and Sound Designer: Dan Jones Illusions: Chris Fisher Comedy Consultant: Clive Mendus Creative Associate: Carolina Valdés You might like to use the internet to research some of these artists to find out more about their careers. If you would like to find out about careers in the theatre, there’s lots of useful information on the Discover Creative Careers website. -

Captain Hook by Shel Silverstein

Captain Hook By Shel Silverstein Read the poem and the drama and then answer the questions. Captain Hook Captain Hook must remember Not to scratch his toes. Captain Hook must watch out And never pick his nose. Captain Hook must be gentle When he shakes your hand. Captain hook must be careful Openin’ sardine cans And playing tag and pouring tea and turnin’ pages of this book. Lots of folks I’m glad I ain’t— But mostly Captain Hook! Drama: CAPTAIN HOOK: Shiver me timbers, Smee! I can’t sleep. I can’t eat. I won’t rest until I find Peter Pan. Just look what he did to me! (Holds up arm with hook.) SMEE: A terrible, terrible thing, Captain. Chopping off your arm! CAPTAIN HOOK: And feeding it to a crocodile. That slithering reptile likes the taste of me! He follows me wherever I go just hoping to get a nibble! (Move up in front of curtain. Close curtain. Lost Boys set up.) [CAPTAIN HOOK sings a song] SMEE: Terrible, terrible! Thank heaven the beast swallowed a clock! CAPTAIN HOOK: That’s the only thing that keeps me alive, Smee. Soon it will wind down and you know what that means. (Uses his finger for tick-tock.) Tick. Tock. Tick. Tock. Tick… (Finger is stuck.) No tock! SMEE: Oh, terrible, terrible! Wait! What’s that I hear ***SOUND CUE Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick- tock… ****Crocodile Sound? CROCODILE enters from behind the audience and slithers up the aisle toward CAPTAIN HOOK. Sound cue continue tick-tocking until CROCODILE exits.) CAPTAIN HOOK: Blame it all on PETER PAN!!! (Runs, exiting.) 1. -

Seasons in Hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Phillip James, "Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3905. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SEASONS IN HELL: CHARLES S. JOHNSON AND THE 1930 LIBERIAN LABOR CRISIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Phillip James Johnson B. A., University of New Orleans, 1993 M. A., University of New Orleans, 1995 May 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first debt of gratitude goes to my wife, Ava Daniel-Johnson, who gave me encouragement through the most difficult of times. The same can be said of my mother, Donna M. Johnson, whose support and understanding over the years no amount of thanks could compensate. The patience, wisdom, and good humor of David H. Culbert, my dissertation adviser, helped enormously during the completion of this project; any student would be wise to follow his example of professionalism. -

Going on the Account: Examining Golden Age Pirates As a Distinct

GOING ON THE ACCOUNT: EXAMINING GOLDEN AGE PIRATES AS A DISTINCT CULTURE THROUGH ARTIFACT PATTERNING by Courtney E. Page December, 2014 Director of Thesis: Dr. Charles R. Ewen Major Department: Anthropology Pirates of the Golden Age (1650-1726) have become the stuff of legend. The way they looked and acted has been variously recorded through the centuries, slowly morphing them into the pirates of today’s fiction. Yet, many of the behaviors that create these images do not preserve in the archaeological environment and are just not good indicators of a pirate. Piracy is an illegal act and as a physical activity, does not survive directly in the archaeological record, making it difficult to study pirates as a distinct maritime culture. This thesis examines the use of artifact patterning to illuminate behavioral differences between pirates and other sailors. A framework for a model reflecting the patterns of artifacts found on pirate shipwrecks is presented. Artifacts from two early eighteenth century British pirate wrecks, Queen Anne’s Revenge (1718) and Whydah (1717) were categorized into five groups reflecting behavior onboard the ship, and frequencies for each group within each assemblage were obtained. The same was done for a British Naval vessel, HMS Invincible (1758), and a merchant vessel, the slaver Henrietta Marie (1699) for comparative purposes. There are not enough data at this time to predict a “pirate pattern” for identifying pirates archaeologically, and many uncontrollable factors negatively impact the data that are available, making a study of artifact frequencies difficult. This research does, however, help to reveal avenues of further study for describing this intriguing sub-culture. -

Reseña De" X Marks the Spot: the Archaeology of Piracy" De Russell K

Caribbean Studies ISSN: 0008-6533 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios del Caribe Puerto Rico Jarvis, Michael Reseña de "X Marks the Spot: The Archaeology of Piracy" de Russell K. Skowronek y Charles R. Ewen, eds. Caribbean Studies, vol. 36, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2008, pp. 208-211 Instituto de Estudios del Caribe San Juan, Puerto Rico Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39215107017 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 208 ÁNGEL A. RIVERA nacionalidades ni proyectos nacionales que intenten homogeneizar a sus miembros. ¿Podría luego pensarse al país y la formación de comunida- des políticas que permitan la contaminación con el otro, la solidaridad infinita y la apertura hacia aquéllos que en realidad nada tienen que ver con uno? Sería interesante, luego, contemplar la creación de un espacio infinitamente solidario y abierto que permita nuevas propuestas políticas que rompan con toda cerrazón nacionalista y con la debacle neoliberal capitalista que en más de un momento ha sido responsable por la situa- ción en que hoy día se encuentra la mayor parte de la humanidad. Russell K. Skowronek and Charles R. Ewen, eds. 2006. X Marks the Spot: The Archaeology of Piracy. Gainesville: Uni- versity Press of Florida. 384 pp. ISBN: 0-8130-2875-2. Michael Jarvis Department of History University of Rochester [email protected] rchaeology and Piracy—highly popular subjects on their own Athat together would make any History or Discovery Channel producer salivate. -

Pirates and Buccaneers of the Atlantic Coast

ITIG CC \ ',:•:. P ROV Please handle this volume with care. The University of Connecticut Libraries, Storrs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/piratesbuccaneerOOsnow PIRATES AND BUCCANEERS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST BY EDWARD ROWE SNOW AUTHOR OF The Islands of Boston Harbor; The Story of Minofs Light; Storms and Shipwrecks of New England; Romance of Boston Bay THE YANKEE PUBLISHING COMPANY 72 Broad Street Boston, Massachusetts Copyright, 1944 By Edward Rowe Snow No part of this book may be used or quoted without the written permission of the author. FIRST EDITION DECEMBER 1944 Boston Printing Company boston, massachusetts PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN MEMORY OF MY GRANDFATHER CAPTAIN JOSHUA NICKERSON ROWE WHO FOUGHT PIRATES WHILE ON THE CLIPPER SHIP CRYSTAL PALACE PREFACE Reader—here is a volume devoted exclusively to the buccaneers and pirates who infested the shores, bays, and islands of the Atlantic Coast of North America. This is no collection of Old Wives' Tales, half-myth, half-truth, handed down from year to year with the story more distorted with each telling, nor is it a work of fiction. This book is an accurate account of the most outstanding pirates who ever visited the shores of the Atlantic Coast. These are stories of stark realism. None of the arti- ficial school of sheltered existence is included. Except for the extreme profanity, blasphemy, and obscenity in which most pirates were adept, everything has been included which is essential for the reader to get a true and fair picture of the life of a sea-rover. -

TREASURE ISLAND the NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS

Maine State Music Theatre Curtis Memorial Library, Topsham Public Library, and Patten Free Library present A STUDY GUIDE TO TREASURE ISLAND The NOVEL and the MUSICAL 2 STUDY MATERIALS TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL Robert Louis Stevenson Page 3 Treasure Island in Literary History Page 5 Fun Facts About the Novel Page 6 Historical Context of the Novel Page 7 Adaptations of Treasure Island on Film and Stage Page 9 Treasure Island: Themes Page 10 Treasure Island: Synopsis of the Novel Page 11 Treasure Island: Characters in the Novel Page 13 Treasure Island: Glossary Page 15 TREASURE ISLAND A Musical Adventure: THE ROBIN & CLARK MUSICAL Artistic Statement Page 18 The Creators of the Musical Page 19 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Themes Page 20 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Synopsis & Songs Page 21 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: Cast of Characters Page 24 Treasure Island A Musical Adventure: World Premiere Page 26 Press Quotes Page 27 QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION Page 28 MSMT’s Treasure Island A Musical Adventure Page 29 3 TREASURE ISLAND: THE NOVEL ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, so at age seventeen, he enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations he traveled to France to be around young writers and painters. -

Monopoly & King

A READER THE LIBERTARIANISM.ORG READER SERIES INTRODUCES THE MAJOR IDEAS AND THINKERS IN THE LIBERTARIAN TRADITION. Who Makes & King Mob Monopoly History Happen? From the ancient origins of their craft, historians have used their work to defend established and powerful interests and regimes. In the modern period, though, historians have emphasized the agency and impact of everyday, average people—common people—without access to conventional political power. Monopoly & King Mob provides readers with dozens of documents from the Early Modern and Modern periods to suggest that the best history is that which accounts for change both “from above” and “from below” in the social hierarchy. When we think of history as the grand timeline of states, politicians, military leaders, great business leaders, and elite philosophers, we skew our view of the world and our ideas about how it works. ANTHONY COMEGNA is the Assistant Editor for Intellectual History at Anthony Comegna Anthony Libertarianism.org and the Cato Institute. He received an MA (2012) and PhD (2016) in Atlantic and American history from the University of Pittsburgh. He produces historical content for Libertarianism.org regularly and is writer/ host of the Liberty Chronicles podcast. $12.95 DESIGN BY: SPENCER FULLER, FACEOUT STUDIO COVER IMAGE: THINKSTOCK Monopoly and King Mob Edited by Anthony Comegna CATO INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. 109318_FM_R2.indd 3 7/24/18 10:47 AM Copyright © 2018 by the Cato Institute. All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-944424-56-5 eISBN: 978-1-944424-57-2 Printed in Canada. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available. 109318_FM_R4.indd 4 25/07/2018 11:38 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: AMERICAN HISTORY, ABOVE AND BELOW .