Piracy: an Elemental Way of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pirates of Penzance

HOT Season for Young People 2014-15 Teacher Guidebook NASHVILLE OPERA SEASON SPONSOR From our Season Sponsor For over 130 years Regions has been proud to be a part of the Middle Tennessee community, growing and thriving as our area has. From the opening of our doors on September 1, 1883, we have committed to this community and our customers. One area that we are strongly committed to is the education of our students. We are proud to support TPAC’s Humanities Outreach in Tennessee Program. What an important sponsorship this is – reaching over 25,000 students and teachers – some students would never see a performing arts production without this program. Regions continues to reinforce its commitment to the communities it serves and in addition to supporting programs such as HOT, we have close to 200 associates teaching financial literacy in classrooms this year. , for giving your students this wonderful opportunity. They will certainly enjoy Thankthe experience. you, Youteachers are creating memories of a lifetime, and Regions is proud to be able to help make this opportunity possible. ExecutiveJim Schmitz Vice President, Area Executive Middle Tennessee Area 2014-15 HOT Season for Young People CONTENTS Dear Teachers~ We are so pleased to be able Opera rehearsal information page 2 to partner with Nashville Opera to bring students to Opera 101 page 3 the invited dress rehearsal Short Explorations page 4 of The Pirates of Penzance. Cast list and We thank Nashville Opera Opera Information NOG-1 for the use of their extensive The Story NOG-2,3 study guide for adults. -

R.B.K.C. Corporate Templates

The Pirates of Penzance Intergenerational Project ‘A creative music project for primary school children and individuals with varying forms and stages of dementia’ April 2015 In partnership with Public Health 1 Contents 1. Summary 3 2. Evaluation strategy 4 3. Project structure 4 4. Aims and Objectives 10 5. Benefits 11 6. Performance day 17 7. Documentation 18 8. Limitations 19 9. Conclusions 19 Appendix A) St Charles – Mood Boards 21 B) Opera rehearsal schedule 29 C) Composed lyrics 31 Throughout this report direct quotes are indicated in blue: A number of service users were really keen to share their school memories, particularly about singing – sometimes positive, sometimes not. One comment which really stuck in my memory was a gentleman describing how he had always wanted to sing at school but had been told he was not good enough, and how he was grateful now for the opportunity (Seth Richardson, Project Manager). 2 Summary Opera Holland Park’s The Pirates of Penzance has proven to be an extremely successful pilot intergenerational project for KS2 primary school children (Year 5) and individuals with varying forms and stages of dementia and Alzheimer’s. Part-funded by Public Health, two KS2 year 5 classes from St Charles Primary School (RBKC) and service users from a nearby Alzheimer’s day centre, Chamberlain House, enjoyed a variety of activities based around popular themes and music from Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance, culminating with a performance of the operetta delivered by a professional cast of opera singers. Participants took part in a series of workshops, both independently and jointly, with children from St Charles Primary School travelling to Chamberlain house for combined sessions. -

Media Piracy in Emerging Economies

MEDIA PIRACY IN EMERGING ECONOMIES Edited by Joe Karaganis Media Piracy in Emerging Economies can be found online at http://piracy.ssrc.org. © 2011 Social Science Research Council All rights reserved. Published by the Social Science Research Council Printed in the United States of America References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor the Social Science Research Council is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. Designed by Rosten Woo Maps by Mark Swindle Cover photo: AFP/Getty Images Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Media Piracy in Emerging Economies ISBN 978-0-98412574-6 1.Information society—Social aspects. 2.Intellectual Property. 3.International business enterprises—Political activity. 4.Blackmarket. I. Social Science Research Council SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH COUNCIL • MEDIA PIRACY IN EMERGING ECONOMIES SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH COUNCIL • MEDIA PIRACY IN EMERGING ECONOMIES Media Piracy in Emerging Economies is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH COUNCIL • MEDIA PIRACY IN EMERGING ECONOMIES SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH COUNCIL • MEDIA PIRACY IN EMERGING ECONOMIES Partnering Organizations The Social Science Research Council New York, NY, USA The Overmundo Institute Rio de Janeiro, Brazil The Center for Technology and Society Getulio Vargas Foundation Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Sarai The Centre for the Study of Developing Societies Delhi, India The Alternative Law Forum Bangalore, India The Association for Progressive Communications Johannesburg, South Africa The Centre for Independent Social Research St. -

Pirates Playbill.Indd

Essgee’s Based on the operetta by W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan The 65th Anniversary Revival of De La Salle’s First-Ever Musical! April 27-29, 2017 De La Salle College Auditorium 131 Farnham Ave. Theatre De La Salle’s Based on the operetta by W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan Additional lyrics by Melvyn Morrow New Orchestrations by Kevin Hocking Original Production Director and Choreographer Craig Shaefer Conceived and Produced by Simon Gallaher Presented in cooperation with David Spicer Productions, Australia www.davidspicer.com.au Music Director Choreographer CHRIS TSUJIUCHI MELISSA RAMOLO Technical Director Set Designer CARLA RITCHIE MICHAEL BAILEY Directed by GLENN CHERNY and MARC LABRIOLA Produced by MICHAEL LUCHKA Essgee’s The Pirates of Penzance, Gilbert and Sullivan for the 21st Century, presented by arrangement with David Spicer Productions www.davidspicer.com.au representing Simon Gallaher and Essgee Entertainment Performance rights for Essgee’s The Pirates of Penzance are handled exclusively in North America by Steele Spring Stage Rights (323) 739-0413, www.stagerights.com I wish to extend to the Cast and Crew my sincerest congratulations on your very wonderful and successful 2017 production of e Pirates of Penzance! William W. Markle, Q.C. Cast Member, 1952 production of Th e Pirates of Penzance De La Salle College “Oaklands” Class of 1956 THE CAST The Pirate King ............................................... CALUM SLAPNICAR Frederic ............................................................. NICHOLAS DE SOUZA Samuel.................................................................... -

Playful Subversions: Hollywood Pirates Plunder Spanish America NINA GERASSI-NAVARRO

Playful Subversions: Hollywood Pirates Plunder Spanish America NINA GERASSI-NAVARRO The figure of the pirate evokes a number of distinct and contrasting images: from a fearless daredevil seeking adventure on the high seas to a dangerous and cruel plunderer moved by greed. Owing obedience to no one and loyal only to those sharing his way of life, the pirate knows no limits other than the sea and respects no laws other than his own. His portrait is both fascinating and frightening. As a hero, he is independent, audacious, intrepid and rebellious. Defying society's rules and authority, sailing off to the unknown in search of treasures, fearing nothing, the pirate is the ultimate symbol of freedom. But he is also a dangerous outlaw, known for his violent tactics and ruthless assaults. The social code he lives by inspires enormous fear, for it is extremely rigid and anyone daring to disobey the rules will suffer severe punishments. These polarized images have captured the imagination of historians and fiction writers alike. Sword in hand, eye-patch, with a hyperbolic mustache and lascivious smile, Captain Hook is perhaps the most obvious image-though burlesque- of the dangerous fictional pirate. His greedy hook destroys everything that crosses his hungry path, even children. On a more serious level, we might think of the tortures the cruel and violent Captain Morgan inflicted upon his enemies, hanging them by their testicles, cutting their ears or tongues off; or of Jean David Nau, the French pirate known as L 'Ollonais (el Olonés in Spanish), who would rip the heart out of his victims if they did not comply with his requests; 1 or even the terrible Blackbeard who enjoyed locking himself up with a few of his men and shooting at them in the dark: «If I don't kill someone every two or three days I will lose their respect» he is said to have claimed justifyingly. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science -

The Gilbert & Sullivan Society of Edinburgh

FCT/PirateProdAd:FCT/PiratesProdAd 27/2/07 14:30 Page 1 edinburgh festival theatre The Gilbert & Sullivan Society of Edinburgh presents The Pirates of Penzance or The Slave of Duty Libretto by Music by W. S. Gilbert Arthur Sullivan Mon 30 April - Sat 5 May 24 - 28 April Director .....................................Alan Borthwick This production celebrates the incredible talent of Hosted by LIONEL BLAIR three world famous entertainers and some of the Choreography by ANTON DU BEKE Musical Director ...............................David Lyle finest music and song that has ever been recorded. & ERIN BOAG Experience Frank, Sammy and Dean’s classic recordings Assistant Director ....................... Liz Landsman Featuring a cast of outstanding world-class dance including: The Lady is a Tramp, Mr Bojangles, I’ve Got You champions, performing a number of styles, including Under My Skin, New York, New York… and many more. the Cha Cha, Salsa, Rumba, Quickstep and many, many more. CHARITY NUMBER: SC027486 http://www.edgas.org/ Box Office 0131 529 6000 Group Bookings 0131 529 6005 Book online www.eft.co.uk BOOKING FEE APPLIES W e l c o m e S y n o p s i s ood evening, Ladies and Gentlemen, and a warm welcome to the King’s Theatre, Edinburgh and to our rederic is a young pirate apprentice who has a somewhat abnormal con- Gproduction of The Pirates of Penzance. science. When he learns that he has been wrongly apprenticed to the The Pirates of Penzance is now reckoned to be Gilbert & Fpirate band he remains true to his indentures until they expire. Today is his Sullivan’s most popular operetta. -

Captain Hook by Shel Silverstein

Captain Hook By Shel Silverstein Read the poem and the drama and then answer the questions. Captain Hook Captain Hook must remember Not to scratch his toes. Captain Hook must watch out And never pick his nose. Captain Hook must be gentle When he shakes your hand. Captain hook must be careful Openin’ sardine cans And playing tag and pouring tea and turnin’ pages of this book. Lots of folks I’m glad I ain’t— But mostly Captain Hook! Drama: CAPTAIN HOOK: Shiver me timbers, Smee! I can’t sleep. I can’t eat. I won’t rest until I find Peter Pan. Just look what he did to me! (Holds up arm with hook.) SMEE: A terrible, terrible thing, Captain. Chopping off your arm! CAPTAIN HOOK: And feeding it to a crocodile. That slithering reptile likes the taste of me! He follows me wherever I go just hoping to get a nibble! (Move up in front of curtain. Close curtain. Lost Boys set up.) [CAPTAIN HOOK sings a song] SMEE: Terrible, terrible! Thank heaven the beast swallowed a clock! CAPTAIN HOOK: That’s the only thing that keeps me alive, Smee. Soon it will wind down and you know what that means. (Uses his finger for tick-tock.) Tick. Tock. Tick. Tock. Tick… (Finger is stuck.) No tock! SMEE: Oh, terrible, terrible! Wait! What’s that I hear ***SOUND CUE Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick- tock… ****Crocodile Sound? CROCODILE enters from behind the audience and slithers up the aisle toward CAPTAIN HOOK. Sound cue continue tick-tocking until CROCODILE exits.) CAPTAIN HOOK: Blame it all on PETER PAN!!! (Runs, exiting.) 1. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

Seasons in Hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Phillip James, "Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3905. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SEASONS IN HELL: CHARLES S. JOHNSON AND THE 1930 LIBERIAN LABOR CRISIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Phillip James Johnson B. A., University of New Orleans, 1993 M. A., University of New Orleans, 1995 May 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first debt of gratitude goes to my wife, Ava Daniel-Johnson, who gave me encouragement through the most difficult of times. The same can be said of my mother, Donna M. Johnson, whose support and understanding over the years no amount of thanks could compensate. The patience, wisdom, and good humor of David H. Culbert, my dissertation adviser, helped enormously during the completion of this project; any student would be wise to follow his example of professionalism. -

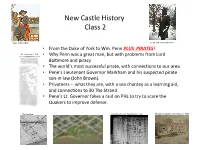

PIRATES! NC Common, 1704 • Why Penn Was a Great Man, but with Problems from Lord Bal�More and Piracy • the World’S Most Successful Pirate, with Connec�Ons to Our Area

New Castle History Class 2 Capt. Kidd in NYC Penn with Livery of Seisin • From the Duke of York to Wm. Penn PLUS PIRATES! NC Common, 1704 • Why Penn was a great man, but with problems from Lord Bal@more and piracy • The world’s most successful pirate, with connec@ons to our area. • Penn's Lieutenant Governor Markham and his suspected pirate son-in-law (John Brown). • Privateers -- what they are, with a sea chantey as a learning aid, and connec@ons to 30 The Strand • Penn's Lt. Governor fakes a raid on PHL to try to scare the Quakers to improve defense. The Fort Lot Imports into East Coast Ports, 1762 Shipping Supplies and Livestock, 1797 Useful Book The Poli@cs of Piracy Crime and Civil Disobedience in Colonial America Douglas R. Burgess, Jr. 2014 (Available at UD E188.B954) Too academic for me to recommend But good detail on Penn, Penn’s Governors, Asembly, Pirates, Law Chapters: § The Sorrowful Tale of Robert Snead [a whistle blower in Philadelphia] § London Fog: A Brief, Confusing History of English Piracy Law § “A Spot upon Our Garment” The Red Sea Fever in Colonial New York [Kidd] § Voyage of the Fancy [Henry Every, world’s most successful pirate] § A tale of two trials § A Society of Friends: Quakers and Illicit Trade in Colonial Pennsylvania People in the Duke of York period (1664-1682) (which like the Dutch period was brief) Elizabeth I, virgin queen, no heir, Protestant James I (as in the Bible) (r1603-1625) Charles I, liberal, religiously tolerant (r1625-1649) Granted Maryland to Lord Bal@more (1632) Beheaded 1649 Oliver Cromwell (r1653- 1658) Adm. -

Going on the Account: Examining Golden Age Pirates As a Distinct

GOING ON THE ACCOUNT: EXAMINING GOLDEN AGE PIRATES AS A DISTINCT CULTURE THROUGH ARTIFACT PATTERNING by Courtney E. Page December, 2014 Director of Thesis: Dr. Charles R. Ewen Major Department: Anthropology Pirates of the Golden Age (1650-1726) have become the stuff of legend. The way they looked and acted has been variously recorded through the centuries, slowly morphing them into the pirates of today’s fiction. Yet, many of the behaviors that create these images do not preserve in the archaeological environment and are just not good indicators of a pirate. Piracy is an illegal act and as a physical activity, does not survive directly in the archaeological record, making it difficult to study pirates as a distinct maritime culture. This thesis examines the use of artifact patterning to illuminate behavioral differences between pirates and other sailors. A framework for a model reflecting the patterns of artifacts found on pirate shipwrecks is presented. Artifacts from two early eighteenth century British pirate wrecks, Queen Anne’s Revenge (1718) and Whydah (1717) were categorized into five groups reflecting behavior onboard the ship, and frequencies for each group within each assemblage were obtained. The same was done for a British Naval vessel, HMS Invincible (1758), and a merchant vessel, the slaver Henrietta Marie (1699) for comparative purposes. There are not enough data at this time to predict a “pirate pattern” for identifying pirates archaeologically, and many uncontrollable factors negatively impact the data that are available, making a study of artifact frequencies difficult. This research does, however, help to reveal avenues of further study for describing this intriguing sub-culture.