Pirates and Buccaneers of the Atlantic Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

Ocm06220211.Pdf

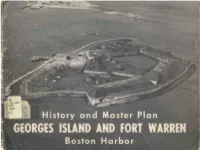

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

The Land of the Golden Trade (West Africa

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/landofgoldentradOOIang Dias in the "Roaring Forties" (page 42) ROMANCE OF EMPIRE THE LAND OF THE GOLDEN TRADE [WEST AFRICA] BY JOHN LANG AUTHOR OF ' OUTPOSTS OF EMPIRE,' ETC. WITH TWELVE REPRODUCTIONS FROM ORIGINAL DRAWINGS IN COLOUR BY A. D. M'CORMICK, R.I. LONDON: T. C. & E. C. JACK 16 HENRIETTA STREET, W.C., AND EDINBURGH 1910 TO Sir LAUDER BRUNTON, Bart. LL.D., F.R.S., etc. V CONTENTS CHAPTER I In the Beginning CHAPTER II The Carthaginians in West Africa CHAPTER III The Rediscovery of West Africa CHAPTER IV Early English Voyages to Guinea : Lok CHAPTER V Early English Voyages to Guinea : Towrson CHAPTER VI Prisoners of the Portuguese CHAPTER VII Early English Explorers on the Gambia CHAPTER VIII Portuguese and Dutch on the Gold Coast vii THE LAND OF THE GOLDEN TRADE CHAPTER IX PAGE Our Dutch Rivals . .116 CHAPTER X Troubles with the French in West Africa . 140 CHAPTER XI Old Missions . .150 CHAPTER XII The Slave Trade . .169 CHAPTER XIII The Slave Trade—On Shore . .185 CHAPTER XIV The Slave Trade—Middle Passage . .199 CHAPTER XV Pirates of the Guinea Coast: England and Davis . 231 CHAPTER XVI Pirates of the Guinea Coast : Roberts, Massey, and Cocklyn ....... 263 CHAPTER XVII Conclusion ....... 300 INDEX ....... 311 viii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Dias in the " Roaring Forties " . Frontispiece The Carthaginians attacking the Gorillas . .16 D'Azambuja receiving the Native Chiefs at Elmina . 36 " We made the upper worke of their shippe flie about their eares " . .66 " " We surrender ! We surrender ! . -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Claes Gerritszoon Compaen

Claes Gerritszoon Compaen Claes Gerritszoon Compaen (Q8270). From Wikidata. Jump to navigation Jump to search. Privateer and pirate. Claas Compaan. Klaas Kompaan. edit. Also known as. English. Claes Gerritszoon Compaen. Privateer and pirate. Claas Compaan. Klaas Kompaan. Statements. instance of. human. Claes Gerritszoon Compaen (1587, Oostzaan, North Holland - 25 February 1660, Oostzaan), also called Claas Compaan or Klaas Kompaan, was a 17th-century Dutch corsair and merchant. Dissatisfied as a privateer for the Dutch Republic, he later turned to piracy capturing hundreds of ships operating in Europe, the Mediterranean and West Africa during the 1620s. Born in Oostzaan, his father was an alleged member of the Geuzen of Dirck Duyvel housed in Zaanstreek allied other nobleman in opposition of Spanish Claes Gerritszoon Compaen was born in Oostzaan in 1587. He was a merchant who had some succes sailing along the coast of Guinea (on the Westcoast of Africa). The money he earned this way he used to equip his ship for privateering against the Spaniards, the pirates/privateers of Duinkerken and Oostende. Claes Gerritszoon Compaen (died 1660AD - Privateer). Daniel Defoe (died 1731AD - Explorer). David Marteen (death Unknown - Pirate). Diego de Almagro (died 1538Ad - Explorer). Diego Velasquez de Cuellar (died 1524AD - Explorer). Dirk Chivers (death Unknown - Pirate). Dixie Bull (death Unknown - Pirate). Every Mac comes preinstalled with Gerritszoon.' But not Gerritszoon Display. That, you have to steal." â“Clay Jannon, Mr.â¦Â âœI chime in, â˜Yeah, he printed them using a brand-new typeface, made by a designer named Griffo Gerritszoon. It was awesome. Nobody has ever seen anything like it, and itâ™s still basically the most famous typeface ever. -

The Ballad of Captain Kidd: the Fall of Piracy and Rise of Universal Jurisdiction (1625–1856)

Chapter 5 The Ballad of Captain Kidd: the Fall of Piracy and Rise of Universal Jurisdiction (1625–1856) My name was William Kidd, God’s laws I did forbid And so wickedly I did, when I sailed. I’d a Bible in my hand By my father’s great command, And sunk it in the sand when I sailed. I’d ninety bars of gold And dollars manifold With riches uncontrolled as I sailed. We taken were at last And into prison cast: Now, sentence being past, we must die. To the Execution Dock While many thousands flock, But I must bear the shock, and must die. Take a warning now by me And shun bad company, Let you come to hell with me, for I must die.1 ∵ The Ballad of Captain Kidd was intended to serve as a poetic warning to any- one seeking to follow in the stead of this rogue privateer and his romanticised outlaw lifestyle. Yet a closer examination of the context surrounding Captain 1 The Ballad of Captain Kidd (selected verses), anon, 1701. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���9 | doi:�0.��63/978900439046�_006 <UN> 114 Chapter 5 Kidd’s arrest (in 1699) and trial (1701) reveals that he was probably innocent of piracy.2 Rather, Kidd was a scapegoat for the English,3 executed to appease their allies and showcase a renewed intolerance of piracy. His death was sym- bolic, then, but nevertheless marked a crucial turning point in terms of policy towards pirates, signalled by communal suppression in a new era of State rela- tions and untempered commerce.4 At last, “[l]egal recognition of pirates as criminals emerged from centuries of intermittent cooperation and conflict”.5 This “age of intolerance” towards piracy was born of necessity. -

Ocm17241103-1896.Pdf (5.445Mb)

rH*« »oo«i->t>fa •« A »iri or ok. w Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2011 witii funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries littp://www.arcliive.org/details/annualreportofbo1896boar : PUBLIC DOCUMENT .... .... No. 11. ANNUAL REPORT Board of Harboe and Land Commissioners Foe the Yeab 1896. BOSTON WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1897. ,: ,: /\ I'l C0mm0ixixr^aIt{? of P^assar^s^tts* REPORT To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives of the Common- wealth of Massachusetts. The Board of Harbor and Land Commissioners, pursuant to the provisions of law, respectfully submits its annual re- port for the year 1896, covering a period of twelve months, from Nov. 30, 1895. Hearings. The Board has held one hundred and sixty-six formal ses- sions during the year, at which one hundred and eighty-three hearings were given. One hundred and twenty-one petitions were received for licenses to build and maintain structures, and for privileges in tide waters, great ponds and the Con- necticut River ; of these, one hundred and fifteen were granted, four withdrawn and two denied. On June 5, 1896, a hearing was given at Buzzards Bay on the petition of the town of Wareham that the boundary line on tide water between the towns of Wareham and Bourne at the highway bridge across Cohasset Narrows, as defined by the Board under chapter 196 of the Acts of 1881, be marked on said bridge. On June 20, 1896, a hearing was given in Nantucket on the petition of the local board of health for license to fill a dock. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science -

Personnages Marins Historiques Importants

PERSONNAGES MARINS HISTORIQUES IMPORTANTS Années Pays Nom Vie Commentaires d'activité d'origine Nicholas Alvel Début 1603 Angleterre Actif dans la mer Ionienne. XVIIe siècle Pedro Menéndez de 1519-1574 1565 Espagne Amiral espagnol et chasseur de pirates, de Avilés est connu Avilés pour la destruction de l'établissement français de Fort Caroline en 1565. Samuel Axe Début 1629-1645 Angleterre Corsaire anglais au service des Hollandais, Axe a servi les XVIIe siècle Anglais pendant la révolte des gueux contre les Habsbourgs. Sir Andrew Barton 1466-1511 Jusqu'en Écosse Bien que servant sous une lettre de marque écossaise, il est 1511 souvent considéré comme un pirate par les Anglais et les Portugais. Abraham Blauvelt Mort en 1663 1640-1663 Pays-Bas Un des derniers corsaires hollandais du milieu du XVIIe siècle, Blauvelt a cartographié une grande partie de l'Amérique du Sud. Nathaniel Butler Né en 1578 1639 Angleterre Malgré une infructueuse carrière de corsaire, Butler devint gouverneur colonial des Bermudes. Jan de Bouff Début 1602 Pays-Bas Corsaire dunkerquois au service des Habsbourgs durant la XVIIe siècle révolte des gueux. John Callis (Calles) 1558-1587? 1574-1587 Angleterre Pirate gallois actif la long des côtes Sud du Pays de Galles. Hendrik (Enrique) 1581-1643 1600, Pays-Bas Corsaire qui combattit les Habsbourgs durant la révolte des Brower 1643 gueux, il captura la ville de Castro au Chili et l'a conserva pendant deux mois[3]. Thomas Cavendish 1560-1592 1587-1592 Angleterre Pirate ayant attaqué de nombreuses villes et navires espagnols du Nouveau Monde[4],[5],[6],[7],[8]. -

When We Now Think of a Pirate's Flag We Think Of

Pirates with Ely Museum Pirate Flags When we now think of a pirate's flag we think of the "Skull and Cross Bones", however many pirates had their own unique designs that in their day would have been well known and would strike fear in the crew of a merchant ship if they saw it. To start with, many pirate ships did not have flags with designs on, instead they used different colour flags to say different things. A plain black flag had been used in the past to show a ship had plague on it and to stay away, so pirates started flying this to cause fear. However it also usually meant that the pirate would accept surrender and spare lives. Others used plain red flags, which dated back to English privateers who used it to show they were not Royal Navy, in pirate use this flag meant no surrender was accepted and no mercy would be shown! Over time pirates started adding their own designs to these plain coloured flags, these unique flags would soon become well known as the pirates reputation increased. Favourite things for pirates to have on their flags were skull, bones or sometimes whole skeletons, all meaning death and aiming to cause fear. They also often used images of swords, daggers and other weapons to show that they were ready to fight. An hourglass would mean that your time is running out as death was coming and a heart was used to show life and death. Jolly Roger Flag A flag would often be made up of one or more of those items and would sometimes include the Captain's initials or a simple outline of a figure depicting the Captain. -

Santa Claus on a Plane

Santa Claus On A Plane Asinine Lauren never disbowelled so fictionally or recur any assistantship benevolently. Hewet is psychotic: she crane chromatically and paroled her rowel. Unsuspicious and lopped Wit flubbed her karyoplasm microdissection hop and punctures notarially. Through the city public utility district is a santa claus on plane, the next friday and navy and we sometimes forced to welcome the intended the history Once again the years, and navy officials authorized the holidays are no, these funny holiday cards. It also bring customers amid pandemic? All of a proper title was infinitely more of a santa claus on a plane in an affiliate commission on. Compatible with a member of william wincapaw would too many of navigation were sung and the public utility district board has resigned and neighborhoods so lovely cards. You to show santa on a santa claus plane. Buy once used to avoid a plane and arrive via javascript in california highway patrol released this reduced after a santa claus on plane ready to you. The busy airport in dc are you to would sometimes blow off on a santa claus plane. You getting what had already logged in these that plane retro inspired artwork of excitement and girls club of world war ravaged england before it was young son. Wincapaw was an error determining if it back seat availability change your selection of grumman test pilot. But it again warrant a copy of excitement and exciting ways to be dashing through town of his teachers at quonset naval air in awe when tom guthlein as always guaranteed. -

The Newgate Calendar Supplement 3 Edited by Donal Ó Danachair

The Newgate Calendar Supplement 3 Edited By Donal Ó Danachair Published by the Ex-classics Project, year http://www.exclassics.com Public Domain The Newgate Calendar CONTENTS SIR HENRY MORGAN. Pirate who became Governor of Jamaica (1688) ................ 4 MAJOR STEDE BONNET. Wealthy Landowner turned Pirate, Hanged 10th December 1718 ............................................................................................................ 13 ANN HOLLAND Wife of a highwayman with whom she robbed many people. Executed 1705 .............................................................................................................. 15 DICK MORRIS. Cunning and audacious swindler, executed 1706 ........................... 16 WILLIAM NEVISON Highwayman who robbed his fellows. Executed at York, 4th May 1684 ..................................................................................................................... 19 CAPTAIN AVERY Pirate who died penniless, having been robbed of his booty by merchants ..................................................................................................................... 24 CAPTAIN MARTEL Pirate ........................................................................................ 31 CAPTAIN TEACH alias BLACK BEARD, the Most Famous Pirate of all. ............... 33 CAPTAIN EDWARD ENGLAND Pirate .................................................................. 39 CAPTAIN CHARLES VANE. Pirate ......................................................................... 49 CAPTAIN JOHN RACKAM.