Faroese (Faringisch, Faroisch, Farisch)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present (Impact: Studies in Language and Society)

<DOCINFO AUTHOR ""TITLE "Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present"SUBJECT "Impact 18"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> Germanic Standardizations Impact: Studies in language and society impact publishes monographs, collective volumes, and text books on topics in sociolinguistics. The scope of the series is broad, with special emphasis on areas such as language planning and language policies; language conflict and language death; language standards and language change; dialectology; diglossia; discourse studies; language and social identity (gender, ethnicity, class, ideology); and history and methods of sociolinguistics. General Editor Associate Editor Annick De Houwer Elizabeth Lanza University of Antwerp University of Oslo Advisory Board Ulrich Ammon William Labov Gerhard Mercator University University of Pennsylvania Jan Blommaert Joseph Lo Bianco Ghent University The Australian National University Paul Drew Peter Nelde University of York Catholic University Brussels Anna Escobar Dennis Preston University of Illinois at Urbana Michigan State University Guus Extra Jeanine Treffers-Daller Tilburg University University of the West of England Margarita Hidalgo Vic Webb San Diego State University University of Pretoria Richard A. Hudson University College London Volume 18 Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche Germanic Standardizations Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert Monash University Wim Vandenbussche Vrije Universiteit Brussel/FWO-Vlaanderen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements 8 of American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Germanic standardizations : past to present / edited by Ana Deumert, Wim Vandenbussche. -

Sprache Der Gegenwart

SPRACHE DER GEGENWART Schriften des Instituts für deutsche Sprache Gemeinsam mit Hans Eggers, Johannes Erben, Odo Leys und Hans Neumann herausgegeben von Hugo Moser Schriftleitung: Ursula Hoberg BAND XXXVII Heinz Kloss DIE ENTWICKLUNG NEUER GERMANISCHER KULTURSPRACHEN SEIT 1800 2., erweiterte Auflage PÄDAGOGISCHER VERLAG SCHWANN DÜSSELDORF CIP-Kurztitelaufnahme der Deutschen Bibliothek Kloss, Heinz: Die Entwicklung neuer germanischer Kultursprachen seit 1800 [achtzehnhundert]. - 2., erw. Aufl. - Düsseldorf: Pädagogischer Verlag Schwann, 1978. (Sprache der Gegenwart; Bd. 37) ISBN 3-590-15637-6 © 1978 Pädagogischer Verlag Schwann Düsseldorf Alle Rechte Vorbehalten ■ 2. Auflage 1978 Umschlaggestaltung Paul Effert Herstellung Lengericher Handelsdruckerei Lengerich (Westf.) ISBN 3-590-15637-6 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 0. Vorbemerkungen 9 0.1. Aus der Geschichte des Buches 9 0.2. Zum Titel des Buches 10 0.3. Einstimmung: Spracherneuerung und Nationalismus 13 1. Der linguistische und der soziologische Sprachbegriff 23 1.1. Über einige sprachsoziologische Grundbegriffe 23 1.1. 1. Ausbau und Abstand 23 1.1.2. Weiteres von den Einzelsprachen 30 1.2. Ausbaufragen 37 1.2.1. Ausbauweisen 37 1.2.2. Sachprosa 40 1.2.3. Ausbauphasen 46 1.2.4. Ausbaudialekte 55 1.2.5. Dachlose Außenmundarten 60 1.3. Abstandfragen 63 1.3.1. Wie m ißt man den Abstand? 63 1.3.2. Plurizentrische Hochsprachen 66 1.3.3. Scheindialektisierte Abstandsprachen 67 1.3.4. Kreolsprachen: ein von der Forschung neu er schlossener Typ von Abstandsprachen 70 1.4. Zusammenfassung und Vorausschau 79 1.4.1. Zusammenfassung des bisher Gesagten 79 1.4.2. Zur Gliederung der im 2. Kapitel näher behandelten Ausbausprachen und Ausbaudialekte 82 1.4.3. -

The Icelandic Language at the Time of the Reformation: Some Reflections on Translations, Language and Foreign Influences

THE ICELANDIC LANGUAGE AT THE TIME OF THE REFORMATION: SOME REFLECTIONS ON TRANSLATIONS, LANGUAGE AND FOREIGN INFLUENCES Veturliði Óskarsson (Uppsala University) Abstract The process of the Reformation in Iceland in its narrow sense is framed by the publication of the New Testament in 1540 and the whole Bible in 1584. It is sometimes believed that Icelandic language would have changed more than what it has, if these translations had not seen the day. During the 16th century, in all 51 books in Icelandic were printed. Almost all are translations, mostly from German. These books contain many loanwords, chiefly of German origin. These words are often a direct result of the Reformation, but some of them are considerably older. As an example, words with the German prefix be- were discussed to some length in the article. Some loanwords from the 16th century have lived on to our time, but many were either wiped out in the Icelandic language purism of the nineteenth and twentieth century, or never became an integrated part of the language, outside of religious and official texts. Some words even only show up in one or two books of the 16th century. The impact of the Reformation on the future development of the Icelandic language, other than a temporary one on the lexicon was limited, and influence on the (spoken) language of common people was probably little. Keywords The Icelandic Reformation, printed books, the New Testament, the Bible, loanwords, the German prefix be-. Introduction The Reformation in Iceland is dated to the year 1550, when the last Catholic bishop in Iceland, Jón Arason of the Hólar diocese in Northern Iceland, was executed. -

Norn Elements in the Shetland Dialect

Hugvísindadeild Norn elements in the Shetland dialect A Historical and Linguistic Review B.A. Essay Auður Dagný Jónsdóttir September, 2013 University of Iceland Faculty of Humanities Department of English Norn elements in the Shetland dialect A Historical and Linguistic Review B.A. Essay Auður Dagný Jónsdóttir Kt.: 270172-5129 Supervisors: Þórhallur Eyþórsson and Pétur Knútsson September, 2013 2 Abstract The languages spoken in Shetland for the last twelve hundred years have ranged from Pictish, Norn to Shetland Scots. The Norn language started to form after the settlements of the Norwegian Vikings in Shetland. When the islands came under the British Crown, Norn was no longer the official language and slowly declined. One of the main reasons the Norn vernacular lived as long as it did, must have been the distance from the mainland of Scotland. Norn was last heard as a mother tongue in the 19th century even though it generally ceased to be spoken in people’s daily life in the 18th century. Some of the elements of Norn, mainly lexis, have been preserved in the Shetland dialect today. Phonetic feature have also been preserved, for example is the consonant’s duration in the Shetland dialect closer to the Norwegian language compared to Scottish Standard English. Recent researches indicate that there is dialectal loss among young adults in Lerwick, where fifty percent of them use only part of the Shetland dialect while the rest speaks Scottish Standard English. 3 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. The origin of Norn ................................................................................................................. 6 3. The heyday of Norn ............................................................................................................... 7 4. King James III and the Reformation .................................................................................. -

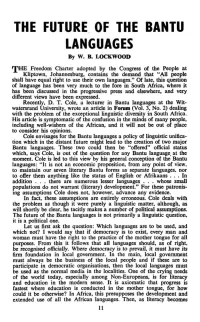

THE FUTURE of the BANTU LANGUAGES by W

THE FUTURE OF THE BANTU LANGUAGES By W. B. LOCKWOOD T^HE Freedom Charter adopted by the Congress of the People at Kliptown, Johannesburg, contains the demand that "All people shall have equal right to use their own languages." Of latef this question of language has been very much to the fore in South Africa, where it has been discussed in the progressive press and elsewhere, and very different views have been expressed. Recently, D. T. Cole, a lecturer in Bantu languages at the Wit- watersrand University, wrote an article in Forum (Vol. 3, No. 2) dealing with the problem of the exceptional linguistic diversity in South Africa. His article is symptomatic of the confusion in the minds of many people, including well-wishers of the African, and it will not be out of place to consider his opinions. Cole envisages for the Bantu languages a policy of linguistic unifica tion which in the distant future might lead to the creation of two major Bantu languages. These two could then be "offered" official status which, says Cole, is out of the question for any Bantu language, at the moment. Cole is led to this view by his general conception of the Bantu languages: "It is not an economic proposition, from any point of view, to maintain our seven literary Bantu forms as separate languages, nor to offer them anything like the status of English or Afrikaans ... In addition . there are numerous lesser languages . whose small populations do not warrant (literary) development." For these patronis ing assumptions Cole does not, however, advance any evidence. -

![Spelling Progress Bulletin Summer 1977 P2 in the Printed Version]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2223/spelling-progress-bulletin-summer-1977-p2-in-the-printed-version-762223.webp)

Spelling Progress Bulletin Summer 1977 P2 in the Printed Version]

Spelling Progress Bulletin Summer, 1977 Dedicated to finding the causes of difficulties in learning reading and spelling. Summer, 1977. Publisht quarterly Editor and General Manager, Assistant Editor, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter. Newell W. Tune, Helen Bonnema Bisgard, Subscription $ 3. 00 a year. 5848 Alcove Ave, 13618 E. Bethany Pl, #307 Volume XVII, no. 2 No. Hollywood, Calif. 91607 Denver, Colo, 80232 Editorial Board: Emmett A. Betts, Helen Bonnema, Godfrey Dewey, Wilbur J. Kupfrian, William J. Reed, Ben D. Wood, Harvie Barnard. Table of Contents 1. Spelling and Phonics II, by Emmett Albert Betts, Ph.D., LL.D. 2. Sounds and Phonograms I (Grapho-Phoneme Variables), by Emmett A. Betts, Ph.D. 3. Sounds and Phonograms II (Variant Spellings), by Emmett Albert Betts, Ph.D, LL.D. 4. Sounds and Phonograms III (Variant Spellings), by Emmett Albert Betts, Ph.D, LL.D. 5. The Development of Danish Orthography, by Mogens Jansen & Tom Harpøth. 6. The Holiday, by Frank T. du Feu. 7. A Decade of Achievement with i. t. a., by John Henry Martin. 8. Ten Years with i. t. a. in California, by Eva Boyd. 9. Logic and Good Judgement needed in Selecting the Symbols to Represent the Sounds of Spoken English, by Newell W. Tune. 10. Criteria for Selecting a System of Reformed Spelling for a Permanent Reform, by Newell W. Tune. 11. Those Dropping Test Scores, by Harvie Barnard. 12. Why Johnny Still Can't Learn to Read, by Newell W. Tune. 13. A Condensed Summary of Reasons For and Against Orthographic Simplification, by Harvie Barnard. 14. An Explanation of Vowels Followed by /r/ in World English Spelling (I. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

Self-Determination and Sub-Sovereign Statehood in the EU with Particular Reference to Scotland and Passing Reference to the Faroe Islands L

Alasdair Geater and Scott Crosbyt Self-determination and Sub-sovereign Statehood in the EU with particular reference to Scotland and passing reference to the Faroe Islands l. Points of Departure II. Fear of Freedom III. Self-Determination as a Fundamental Human Right IV. Arguments of Dissuasion and their Rebuttal On the perceived dangers of nationafis m On the perceived risk of economic isolation On the fe ar of fragmentation IV. The Exercise of the Right of Self-determination under EU Law VI. The Importance of History VII. The Particular Case of Scotland Historical Constitutional Consequences of Scottish Statehood The Process The benefits of statehood ? 1 Partners respectively in Geater and Co and Stanbrook & Hooper, Brussels and faunding partners of Geater & Crosby, a joint venture devoted to Scots constitutional law, also based in Brussels. The seeds for this discourse were sown in a leeture in 1975 by Professor Neil MacCormick, then ayoung Dean of the Faculty of Law at Edinburgh University, which the younger of the co authors attended (and remembered). Føroyskt L6gar Rit (Faroese Law Review) vol. 1 no. 1 - 2001 "In a united Europe every small country can find its place alongside the former great powers" 2 Føroyskt Urtak Heiti: Sjalvsavgeroarrættur og at vera statur f ES viiJ partvisum fullveldi, vio serligum atliti til Skotlands, men eisini vio atliti til Føroya. Greinin vioger [ heimspekiligum og politiskum høpi tjdningin av, at tj6oir, sum nu eru i felagskapi viiJ aorar i ES, faa fullveldi og egnan ES-limaskap. Høvundarnir halda uppa, at tao er 6missandi rættur f fullum samsvari vio ES-Sattmalan hja hesum tj6oum at faa egnan ES-limaskap. -

The Position of Frisian in the Germanic Language Area Charlotte

The Position of Frisian in the Germanic Language Area Charlotte Gooskens and Wilbert Heeringa 1. Introduction Among the Germanic varieties the Frisian varieties in the Dutch province of Friesland have their own position. The Frisians are proud of their language and more than 350,000 inhabitants of the province of Friesland speak Frisian every day. Heeringa (2004) shows that among the dialects in the Dutch language area the Frisian varieties are most distant with respect to standard Dutch. This may justify the fact that Frisian is recognized as a second official language in the Netherlands. In addition to Frisian, in some towns and on some islands a mixed variety is used which is an intermediate form between Frisian and Dutch. The variety spoken in the Frisian towns is known as Town Frisian1. The Frisian language has existed for more than 2000 years. Genetically the Frisian dialects are most closely related to the English language. However, historical events have caused the English and the Frisian language to diverge, while Dutch and Frisian have converged. The linguistic distance to the other Germanic languages has also altered in the course of history due to different degrees of linguistic contact. As a result traditional genetic trees do not give an up-to-date representation of the distance between the modern Germanic languages. In the present investigation we measured linguistic distances between Frisian and the other Germanic languages in order to get an impression of the effect of genetic relationship and language contact for the position of the modern Frisian language on the Germanic language map. -

What Can Faroese Pseudocoordination Tell Us About English Inflection?

What can Faroese pseudocoordination tell us about English inflection? Daniel Ross University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1 Introduction English, with its relatively impoverished morphology within Germanic, offers no evidence for determining whether a given verb form is inflected identically to the lexical root or not inflected at all. Furthermore, it is unclear whether all such identical forms are accidentally homophonous or are indications of systematic syncretism that is part of the mechanics of the morphosyntax of the language. This article addresses a particular morphosyntactic phenomenon for which this distinction has greater implications for the grammar. Does the grammar allow for specific requirements of uninflected verbal forms in certain constructions? Are uninflected present-tense forms of the verb systematically equivalent to the infinitive in a way that is operational in the grammar? Specifically, the ban on inflection found in English try and pseudocoordination is investigated in detail. As shown in (1), the construction is permitted if and only if both verbs happen to be in their uninflected forms.1 (1) a. Try and win the race! [Then even if you do not succeed, you tried.] b. I will try and win the race [but I am tired and might not be able to win]. c. I try and win the race every time [even though I rarely succeed]. d. *He tries and win(s) the race every time [but he rarely succeeds]. e. He did try and win the race [but his injury made it impossible]. f. *He tried and win/won the race [but his injury made it impossible]. -

Consonant Insertions: a Synchronic and Diachronic Account of Amfo'an

Consonant Insertions: A synchronic and diachronic account of Amfo'an Kirsten Culhane A thesis submitted for the degree of Bachelor ofArts with Honours in Language Studies The Australian National University November 2018 This thesis represents an original piece of work, and does not contain, inpart or in full, the published work of any other individual, except where acknowl- edged. Kirsten Culhane November 2018 Abstract This thesis is a study of synchronic consonant insertions' inAmfo an, a variety of Meto (Austronesian) spoken in Western Timor. Amfo'an attests synchronic conso- nant insertion in two environments: before vowel-initial enclitics and to mark the right edge of the noun phrase. This constitutes two synchronic processes; the first is a process of epenthesis, while the second is a phonologically conditioned affixation process. Which consonant is inserted is determined by the preceding vowel: /ʤ/ occurs after /i/, /l/ after /e/ and /ɡw/ after /o/ and /u/. However, there isnoregular process of insertion after /a/ final words. This thesis provides a detailed analysis of the form, functions and distribution of consonant insertion in Amfo'an and accounts for the lack of synchronic consonant insertion after /a/-final words. Although these processes can be accounted forsyn- chronically, a diachronic account is also necessary in order to fully account for why /ʤ/, /l/ and /ɡw/ are regularly inserted in Amfo'an. This account demonstrates that although consonant insertion in Amfo'an is an unusual synchronic process, it is a result of regular sound changes. This thesis also examines the theoretical and typological implications 'of theAmfo an data, demonstrating that Amfo'an does not fit in to the categories previously used to classify consonant/zero alternations. -

The History of Language in Shetland

Language in Shetland We don’t know much about Pre-300AD the people of Shetland or Before the Picts The history of their language. Pictish people carve symbols 300AD-800AD language in into stone and speak a ‘Celtic’ Picts language. Shetland Vikings occupy the isles and introduce ‘Norn’. They carve S1-3 800AD-1500AD symbols called ‘runes’ into Vikings stone. The Picts and their language are then wiped out by Vikings. Scotland rule gradually influences life on the islands. The Scottish language 1500AD onwards eventually becomes the Scots prominent language. The dialect Shetlanders Today speak with today contains Us! Scottish and Norn words. 2 THE PICTS Ogham alphabet Some carvings are part of an The Picts spoke a Celtic The Picts lived in mainland alphabet called ‘ogham’. Ogham language, originating from Scotland from around the 6th represents the spoken language of Ireland. Picts may have to the 9th Century, possibly the Picts, by using a ‘stem’ with travelled from Ireland, earlier. Indications of a shorter lines across it or on either Scotland or further afield burial at Sumburgh suggest side of it. to settle on Shetland. that Picts had probably settled in Shetland by There are seven ogham ogham.celt.dias.ie 300AD. inscriptions from Shetland Picts in Shetland spoke one of (including St Ninian’s Isle, The side, number and angle of the the ‘strands’ of the Celtic Cunningsburgh and Bressay) short lines to the stem indicates the language. Picts also carved symbols onto and one from a peat bog in intended sound. Lunnasting. stone. These symbols have been found throughout These symbol stones may Scotland—common symbols have been grave markers, or This inscribed sandstone was dug they may have indicated up from the area of the ancient must have been understood by gathering points.