The Distribution of Definiteness Markers and the Growth of Syntactic Structure from Old Norse to Modern Faroese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

Student Handbook

2018/2019 Student Handbook . University of the Faroe Islands 2018/2019 1 2 INTRODUCTION Dear student, Welcome to the University of the Faroe Islands. You are now embarking upon a new period of your life, where you have chosen to attend university. Our wish is that your time spent studying here will be positive, instructive, and stimulating. At the University of the Faroe Islands it is important to us that as a student you feel as welcome as possible, that you receive a great start to your studies and good studying habits, that your well-being is a priority, and that your time spent at the university will be both challenging, constructive, and exciting. We encourage you as a student to be active, to participate in social activities or events, and to bring your own personal contribution to a good and constructive academic environment, so that you play a part in promoting well-being – both for yourself and for your fellow students. It is, among others, productive students who have helped making the university known for being a good place to study. The fact that the various offered programmes are located at several separate places in the city, makes it even more necessary that the students and staff participate in communal arrangements for everyone, and thereby play their part in developing a feeling of communal identity and increased well-being. The staff at the university is also there to help, guide, and support you in reaching your educational goals. Those who are first and foremost available to you are: the department offices, the Student Services Centre and the student counsellors. -

The Postcolonial North Atlantic Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands

The Postcolonial North Atlantic Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands Edited by Lill-Ann Körber and Ebbe Volquardsen Nordeuropa-Institut der Humboldt-Universität Berlin Table of Contents EBBE VOLQUARDSEN/LILL-ANN KÖRBER The Postcolonial North Atlantic: An Introduction WILLIAM FROST The Concept of the North Atlantic Rim; or, Questioning the North Iceland GUÐMUNDUR HÁLFDANARSON Iceland Perceived: Nordic, European or a Colonial Other? KRISTÍN LOFTSDÓTTIR Icelandic Identities in a Postcolonial Context ANN-SOFIE NIELSEN GREMAUD Iceland as Centre and Periphery: Postcolonial and Crypto-colonial Perspectives REINHARD HENNIG Postcolonial Ecology: An Ecocritical Reading of Andri Snær Magnason’s Dreamland: A Self-Help Manual for a Frightened Nation () HELGA BIRGISDÓTTIR Searching for a Home, Searching for a Language: Jón Sveinsson, the Nonni Books and Identity Formation DAGNÝ KRISTJÁNSDÓTTIR Guðríður Símonardóttir: The Suspect Victim of the Turkish Abductions in the th Century Faroe IslanDs BERGUR RØNNE MOBERG The Faroese Rest in the West: Danish-Faroese World Literature between Postcolonialism and Western Modernism 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS MALAN MARNERSDÓTTIR Translations of William Heinesen – a Post-colonial Experience CHRISTIAN REBHAN Postcolonial Politics and the Debates on Membership in the European Communities in the Faroe Islands (–) JOHN K. MITCHINSON Othering the Other: Language Decolonisation in the Faroe Islands ANNE-KARI SKARÐHAMAR To Be or Not to Be a Nation: Representations of Decolonisation and Faroese Nation Building in Gunnar Hoydal’s Novel Í havsins hjarta () Greenland BIRGIT KLEIST PEDERSEN Greenlandic Images and the Post-colonial: Is it such a Big Deal after all? CHRISTINA JUST A Short Story of the Greenlandic Theatre: From Fjaltring, Jutland, to the National Theatre in Nuuk, Greenland KIRSTEN THISTED Politics, Oil and Rock ‘n’ Roll. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

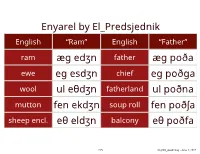

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present (Impact: Studies in Language and Society)

<DOCINFO AUTHOR ""TITLE "Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present"SUBJECT "Impact 18"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> Germanic Standardizations Impact: Studies in language and society impact publishes monographs, collective volumes, and text books on topics in sociolinguistics. The scope of the series is broad, with special emphasis on areas such as language planning and language policies; language conflict and language death; language standards and language change; dialectology; diglossia; discourse studies; language and social identity (gender, ethnicity, class, ideology); and history and methods of sociolinguistics. General Editor Associate Editor Annick De Houwer Elizabeth Lanza University of Antwerp University of Oslo Advisory Board Ulrich Ammon William Labov Gerhard Mercator University University of Pennsylvania Jan Blommaert Joseph Lo Bianco Ghent University The Australian National University Paul Drew Peter Nelde University of York Catholic University Brussels Anna Escobar Dennis Preston University of Illinois at Urbana Michigan State University Guus Extra Jeanine Treffers-Daller Tilburg University University of the West of England Margarita Hidalgo Vic Webb San Diego State University University of Pretoria Richard A. Hudson University College London Volume 18 Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche Germanic Standardizations Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert Monash University Wim Vandenbussche Vrije Universiteit Brussel/FWO-Vlaanderen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements 8 of American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Germanic standardizations : past to present / edited by Ana Deumert, Wim Vandenbussche. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

Looking for Parametric Correlations Within Faroese Höskuldur Thráinsson University of Iceland

Looking for parametric correlations within Faroese Höskuldur Thráinsson University of Iceland Abstract: This paper first reviews some parameters that have been suggested to account for variation within Scandinavian, focussing for concreteness on the parameters proposed by Holmberg and Platzack (1995) and Bobaljik and Thráinsson (1998). As this review shows, Faroese is not as well behaved as the parametric approach to Scandinavian syntax would lead us to expect. In addition, the variation found within Faroese syntax is often gradient and not as categorical as the conventional parametric approach to variation would predict. Yet it can be shown that some of the correlations predicted by Holmberg and Platzack’s (1995) Agr Parameter and Bobaljik and Thráinsson’s (1998) Split IP Parameter are found in Faroese syntax and they are turn out to be statistically significant. In the final section it is argued that to account for facts of this sort we need to revise our ideas about parametric variation, language acquisition and the nature of internalized grammars — and that this will be necessary regardless of what we think of the particular formulation of parameters assumed by Holmberg and Platzack on the one hand and Bobaljik and Thráinsson on the other. 1. Parametric variation in Scandinavian syntax1 1.1. The agreement parameter and the case parameter In their comparative work on Scandinavian around 1990, which culminated in their influential book On the Role of Inflection in Scandinavian Syntax (1995), Holmberg and Platzack (henceforth H&P or P&H, depending on the order of authors in the relevant publications) divide the Scandinavian languages into two main groups, i.e. -

Faroe Islands and Greenland 2008

N O R D I C M E D I A T R E N D S 10 Media and Communication Statistics Faroe Islands and Greenland 2008 Compiled by Ragnar Karlsson NORDICOM UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG 2008 NORDICOM’s activities are based on broad and extensive network of contacts and collaboration with members of the research community, media companies, politicians, regulators, teachers, librarians, and so forth, around the world. The activities at Nordicom are characterized by three main working areas. Media and Communication Research Findings in the Nordic Countries Nordicom publishes a Nordic journal, Nordicom Information, and an English language journal, Nordicom Review (refereed), as well as anthologies and other reports in both Nordic and English langu- ages. Different research databases concerning, among other things, scientific literature and ongoing research are updated continuously and are available on the Internet. Nordicom has the character of a hub of Nordic cooperation in media research. Making Nordic research in the field of mass communication and media studies known to colleagues and others outside the region, and weaving and supporting networks of collaboration between the Nordic research communities and colleagues abroad are two prime facets of the Nordicom work. The documentation services are based on work performed in national documentation centres at- tached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. Trends and Developments in the Media Sectors in the Nordic Countries Nordicom compiles and collates media statistics for the whole of the Nordic region. The statistics, to- gether with qualified analyses, are published in the series, Nordic Media Trends, and on the homepage. -

THE FUTURE of the BANTU LANGUAGES by W

THE FUTURE OF THE BANTU LANGUAGES By W. B. LOCKWOOD T^HE Freedom Charter adopted by the Congress of the People at Kliptown, Johannesburg, contains the demand that "All people shall have equal right to use their own languages." Of latef this question of language has been very much to the fore in South Africa, where it has been discussed in the progressive press and elsewhere, and very different views have been expressed. Recently, D. T. Cole, a lecturer in Bantu languages at the Wit- watersrand University, wrote an article in Forum (Vol. 3, No. 2) dealing with the problem of the exceptional linguistic diversity in South Africa. His article is symptomatic of the confusion in the minds of many people, including well-wishers of the African, and it will not be out of place to consider his opinions. Cole envisages for the Bantu languages a policy of linguistic unifica tion which in the distant future might lead to the creation of two major Bantu languages. These two could then be "offered" official status which, says Cole, is out of the question for any Bantu language, at the moment. Cole is led to this view by his general conception of the Bantu languages: "It is not an economic proposition, from any point of view, to maintain our seven literary Bantu forms as separate languages, nor to offer them anything like the status of English or Afrikaans ... In addition . there are numerous lesser languages . whose small populations do not warrant (literary) development." For these patronis ing assumptions Cole does not, however, advance any evidence.