Andra Kalnača a Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

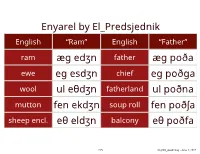

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Participant-Internal Possibility Modality and It's

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 5 S2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy September 2015 Participant-internal Possibility Modality and It’s Coding by – A Bil Analytical Construction in Kazakh Gulzada Salmyrzakyzy Yeshniyaz Botagoz Ermekovna Tassyrova Dauren Bakhytzhanovich Boranbayev Kazakh Ablai Khan University of international relations and world languages, The Republic of Kazakhstan 050022, Almaty, Muratbaev Street, 200 Ruslan Askarbekovich Yermagambetov The Korkyt Ata Kyzylorda State University, The Republic of Kazakhstan, 120014, Kyzylorda, Aiteke Bie Street, 29A Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s2p211 Abstract This paper discusses the semantic paradigm of the participant-internal possibility modality as a subcategory of modality and it’s coding in Kazakh with –A bil analytical construction. We will show that –A bil expresses all semantic properties of participant- internal possibility modality such as inherent/ learnt and mental/physical. Therefore constitutes the core of the functional- semantic field of the given modality. The paper also accounts for the relation of –A bil in modal usage with other category operators such as aspect, tense and voice. Keywords: modality, ability, participant-internal, converb, functional approach 1. Introduction Despite the available vast literature on modality there is still does not exist the single definition of the domain of modality in linguistics. Mostly modality is understood as a united meaning of its subcategories which are still under scrutiny and new concepts are being offered which make difficult to stabilize the semantics of modality. It is not once noted that “the number of modalities one decide upon is to some extent a matter of different ways of slicing the same cake” (Perkins, 1983, p.10). -

Epistemic Modality: English Must, Have to and Have Got to and Their Correspondences in Lithuanian

ISSN 1392–1517. Online ISSN 2029–8315. KALBOTYRA. 2016 • 69 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Klbt.2016.10374 (Non)epistemic modality: English must, have to and have got to and their correspondences in Lithuanian Audronė Šolienė Department of English Philology Vilnius University Universiteto g. 5 LT-01513 Vilnius, Lithuania Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper deals with the three types of modality – epistemic, deontic and dynamic. It examines the relation between the synchronic uses of the modal auxiliary must and the semi-modals have to and have got to as well as their Lithuanian translation correspondences (TCs) found in a bidirectional translation corpus. The study exploits quantitative and qualitative methods of research. The purpose is to find out which type of modality is most common in the use of must, have to and have got to; to establish their equivalents in Lithuanian in terms of congruent or non-congruent correspondence (Johansson 2007); and to determine how Lithuanian TCs (verbs or adverbials) correlate with different types of modality expressed. The analysis has shown that must is mostly used to convey epistemic nuances, while have to and have got to feature in non-epistemic environments. The findings show that must can boast of a great diversity of TCs. Some of them may serve as epistemic markers; others appear in deontic domains only. Have (got) to, on the other hand, is usually rendered by the modal verbs reikėti ‘need’ and turėti ‘must/have to’, which usually encode deontic modality. Key words: modality, epistemic, deontic, dynamic, necessity, obligation, translational correspondence, corpus-based analysis (Ne)episteminis modalumas: anglų kalbos must, have to ir have got to bei jų vertimo atitikmenys lietuvių kalboje Santrauka Šio darbo objektas yra trys anglų kalbos modaliniai veiksmažodžiai – must ‘turėti/ privalėti’, have to ir have got to ‘turėti/reikėti’ ir jų vertimo atitikmenys lietuvių kalboje. -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

MIINA NORVIK Future Time Reference Devices in Livonian in a Finnic Context

DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 25 MIINA NORVIK Future time reference devices in Livonian in a Finnic context Tartu 2015 ISSN 1406-5657 ISBN 978-9949-32-962-5 DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 25 DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 25 MIINA NORVIK Future time reference devices in Livonian in a Finnic context University of Tartu, Institute of Estonian and General Linguistics Dissertation accepted for the commencement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy on September 1st, 2015 by the Committee of the Institute of Estonian and General Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Tartu Supervisors: Professor Karl Pajusalu, University of Tartu Professor Helle Metslang, University of Tartu Opponent: Professor Andra Kalnača, University of Latvia th Commencement: November 12 , 2015 at 14.15, room 139 in University main building, Ülikooli 18, Tartu This study has been supported by the European Social Fund Copyright: Miina Norvik, 2015 ISSN 1406-5657 ISBN 978-9949-32-962-5 (print) ISBN 978-9949-32-963-2 (pdf) University of Tartu Press www.tyk.ee FOREWORD In autumn 2004, I came to the University of Tartu with the idea of studying English language and literature as my major and law as my minor. But after I attended the first introductory course in general linguistics taught by Renate Pajusalu, I changed my mind and decided to go deeper into linguistics. So I took Estonian and Finno-Ugric linguistics as my minor. I became interested in tense, aspect and modality when being a Bachelor’s student. In a seminar paper I discussed the use of past tenses; in my Bachelor’s thesis I concentrated on the progressive aspect in English and Estonian. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or irxiistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* THE GENDER OF INANIMATE INDECLINABLE COMMON NOUNS IN MODERN RUSSIAN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Diaima L. Murphy, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Anelya Rugaleva, Adviser — ^ Adviser Professor Daniel Collins Department of Slavic and East European Languages and Literatures Professor Brian Joseph UMI Number 9962434 UMI* UMI Microform9962434 Copyright 2000 by Bell & Howell information and Leaming Company. -

CLIPP Christiani Lehmanni Inedita, Publicanda, Publicata Speech-Act

CLIPP Christiani Lehmanni inedita, publicanda, publicata titulus Speech-act participants in modality huius textus situs retis mundialis http://www.christianlehmann.eu/publ/lehmann_modality.pdf dies manuscripti postremum modificati 15.06.2012 occasio orationis habitae International Conference on Discorse and Grammar, Ghent University College, May 23-24, 2008 volumen publicationem continens ignotum annus publicationis ignotus paginae ignotae Speech-act participants in modality Christian Lehmann University of Erfurt Abstract Semantic accounts of subjective modality commonly assume that the speaker is the source of modal attitudes. However, there is a large body of data to suggest that attribut- ing a certain subjective modality to the speaker is the default only for the declarative sen- tence type. In interrogative sentences, it is often systematically the hearer who is credited with the modal attitude. For instance, Linda may go is commonly interpreted as ‘I allow Linda to go’. However, the interrogative version may Linda go? usually means ‘do you allow Linda to go?’ rather than ‘do I allow Linda to go?’ Modal operators from a small set of diverse language (English may , German sollen , Ko- rean -kess , Yucatec he’l , the Amharic and Kambaata jussive) are analyzed from the point of view of the shift of the modal assessor depending on sentence type. Some parallels from evidentiality and egophora are drawn. The result may be summarized as follows: By inferences or rules of grammar , subjective modalities may be attributed to a speech-act participant as their source. In declaratives, that is the speaker. In interrogatives, the speaker cedes the decision on the pragmatic focus to the hearer. -

A Linguistically-Motivated Annotation Model of Modality in English and Spanish: Insights from MULTINOT

LiLT volume 14, issue (4) August 2016 A linguistically-motivated annotation model of modality in English and Spanish: Insights from MULTINOT Julia LAVID, Marta CARRETERO and Juan Rafael ZAMORANO-MANSILLA, Universidad Complutense de Madrid Abstract In this paper we present current work on the design and validation of a linguistically-motivated annotation model of modality in English and Spanish in the context of the MULTINOT project.1 Our annotation model captures four basic modal meanings and their subtypes, on the one hand, and provides a fine-grained characterisation of the syntactic realisations of those meanings in English and Spanish, on the other. We validate the modal tagset proposed through an agreement study per- formed on a bilingual sample of four hundred sentences extracted from original texts of the MULTINOT corpus, and discuss the difficult cases encountered in the annotation experiment. We also describe current steps in the implementation of the proposed scheme for the large-scale annotation of the bilingual corpus using both automatic and manual procedures. 1The MULTINOT project is financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, under grant number FF2012-32201. We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Spanish authorities. We also thank the comments and suggestions provided by the anonymous reviewers which have helped to improve the current manuscript. 1 2 / LiLT volume 14, issue (4) August 2016 1 Introduction In this paper we describe the construction and empirical validation of a modality annotation scheme for English and Spanish in the context of the MULTINOT project, whose main aim is the development of a parallel English-Spanish corpus which is balanced – in terms of register diversity and translation directions – and whose design and enrichment with multiple layers of linguistic annotations focuses on quality rather than on quantity (see Lavid et al. -

Latgalian, a Short Grammar of (Nau).Pdf

Languages of the World/Materials 482 A short grammar of Latgal ian Nicole Nau full text research abstracts of all titles monthly updates 2011 LINCOM EUROPA LATGALIAN LW/M482 Published by LINCOM GmbH 2011. Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................ 3 LINCOMGmbH 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Gmunder Str. 35 J .1 General information .................................................................................................. 4 D-81379 Muenchen 1.2 History ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Research and description ........................................................................................... 7 [email protected] 1.4 Typological overview ................................................................................................ 8 www.lincom-europa.com 2. The sound system ..................................................................................................... 9 2. 1 Phonemes, sounds, and letters ................................................................................... 9 webshop: www.lincom-shop.eu 2.2 Stress and tone ......................................................................................................... 13 2.3 Phonological processes ..........................................................................................