Baltic Languages and White Nights Contacts Between Baltic and Uralic Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

INHALT DES 34. BANDES Editorial .............................................................................................. 1 ORIGINALIA Svetlana Burkova : On the grammatical status of the -bcu form in Tundra Nenets ............................................................................................ 3 Rita Csiszár: The Role of Minority Mother Tongue within the Austrian Minority Policy – with Special Focus on Hungarians of Autochthounous and Migrant Origin Living in Austria ................... 37 Merlijn de Smit: The polypersonal passives of Old Finnish .................. 51 DISKUSSION UND KRITIK Rogier Blokland: Rezension Salis-Livisches Wörterbuch. Herausgegeben von Eberhard Winkler und Karl Pajusalu. Linguistica Uralica. Supplementary Series. Volume 3. Tallinn: Teaduste Akadeemia Kirjastus ......................................................................................... 75 Simon Mulder: Rezension Blokland, Rogier: The Russian Loanwords in Literary Estonian. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2009. (VSUA 78) – Linde, Paul van: The Finnic vocabulary against the background of interference. Ph.D. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. 2007. – Bentlin, Mikko: Niederdeutsch-finnische Sprachkontakte. Der lexikalische Einfluß des Niederdeutschen auf die finnische Sprache während des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit. Helsinki: Suomalais-ugrilainen seura 2008. (MSFOu 256) .............................................................. 81 Michael Rießler: Rezension Allemann, Lukas: Die Samen der Kola- Halbinsel: Über das Leben einer ethnischen -

VALTS ERNÇSTREITS (Riga) LIVONIAN ORTHOGRAPHY Introduction the Livonian Language Has Been Extensively Written for About

Linguistica Uralica XLIII 2007 1 VALTS ERNÇSTREITS (Riga) LIVONIAN ORTHOGRAPHY Abstract. This article deals with the development of Livonian written language and the related matters starting from the publication of first Livonian books until present day. In total four different spelling systems have been used in Livonian publications. The first books in Livonian appeared in 1863 using phonetic transcription. In 1880, the Gospel of Matthew was published in Eastern and Western Livonian dialects and used Gothic script and a spelling system similar to old Latvian orthography. In 1920, an East Livonian written standard was established by the simplification of the Finno-Ugric phonetic transcription. Later, elements of Latvian orthography, and after 1931 also West Livonian characteristics, were added. Starting from the 1970s and due to a considerable decrease in the number of Livonian mother tongue speakers in the second half of the 20th century the orthography was modified to be even more phonetic in the interest of those who did not speak the language. Additionally, in the 1930s, a spelling system which was better suited for conveying certain phonetic phenomena than the usual standard was used in two books but did not find any wider usage. Keywords: Livonian, standard language, orthography. Introduction The Livonian language has been extensively written for about 150 years by linguists who have been noting down examples of the language as well as the Livonians themselves when publishing different materials. The prime consideration for both of these groups has been how to best represent the Livonian language in the written form. The area of interest for the linguists has been the written representation of the language with maximal phonetic precision. -

Balodis LU 100 Prezentācija 2019

A Small Nation with a Big Vision: Bringing the Livonians into the Digital Space Dr. phil. Uldis Balodis University of Latvia Livonian Institute The Livonians The Livonian The University of Latvia Livonian Institute Institute: Our first year A Force for Challenges faced by smaller nations Innovation Digital solutions offered by the UL Livonian Institute The Future Livonian is a Finnic language historically spoken in northern Courland/Kurzeme and along both sides of the Gulf of Rīga coast In the early 20th century, the Livonians lived in a string small villages in northern Courland (Kurzeme) With the onset of the Soviet occupation, this area was designated a border zone, which denied the Livonians access to their The Livonians traditional form of livelihood (fishing). As a result of WWII and the border zone, the Livonians were scattered across Latvia and the world ~30 people can communicate in Livonian ~250 individuals consider themselves Livonian according to the last Latvian national census in 2011 The Livonians Latvia in the 12th century (Livonians in purple). Source: laaj.org.au Livonian villages in northern Courland (late 19th-mid-2oth century). Source: virtuallivonia.info The UL Livonian Institute was established in September 2018 and UL Livonian is one of the newest institutes at the University of Latvia. Institute The only research institution – not just in Latvia but in the entire world – devoted to the study of topics pertaining to Latvia’s other indigenous nation: the Livonians. Background Established as part of -

Karlis Ulmanis: from University of Nebraska Graduate to President of Latvia

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Karlis Ulmanis: From University of Nebraska Graduate to President of Latvia Full Citation: Lawrence E Murphy, Aivars G Ronis, and Arijs R Liepins, “Karlis Ulmanis: From University of Nebraska Graduate to President of Latvia,” Nebraska History 80 (1999): 46-54 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1999Ulmanis.pdf Date: 11/30/2012 Article Summary: Karlis Ulmanis studied and then taught briefly at the University of Nebraska as a Latvian refugee. As president of Latvia years later, he shared his enthusiasm for Nebraska traditions with citizens of his country. Cataloging Information: Names: Karlis Augusts Ulmanis, Howard R Smith, Jerome Warner, Charles J Warner, Karl Kleege (orininally Kliegis), Theodore Kleege, Herman Kleege, Val Kuska, Howard J Gramlich, Vere Culver, Harry B Coffee, J Gordon Roberts, A L Haecker, Hermanis Endzelins, Guntis -

VAP 25 Riga Report 2001

THE UNIVERSITIES PROJECT OF THE SALZBURG SEMINAR VISITING ADVISORS' REPORT UNIVERSITY OF LATVIA RIGA, LATVIA APRIL 23-27, 2001 Team Members Dr. John W. Ryan (team leader), Chancellor Emeritus, State University of New York Dr. Achim Mehlhorn, Rector, Technical University of Dresden Dr. Janina Jozwiak, former Rector, Warsaw School of Economics Ms. Martha Gecek, Coordinator, Visiting Advisors Program, Salzburg Seminar; Administrative Director, American Studies Center University of Latvia Team Members Dr. Ivars Lacis, Rector Dr. Juris Krumins, Vice Rector for Studies Dr. Indrikis Muiznieks, Vice Rector for Research Mr. Pavels Fricbergs, Chancellor Mr. Atis Peics, Director Mr. Janis Stonis, Administrative Director Dr. Dace Gertnere, Head, Department of Research Ms. Alina Grzhibovska, Head, Department of International Relations Dr. Lolita Spruge, Head, Department of Studies The University of Latvia is the only classical university in Latvia, thus the main center for higher education, research, and culture for the humanities, natural sciences, and social sciences. It was founded in 1919, building upon the Riga Polytechnic (founded in 1862) and currently comprises thirteen faculties and more than thirty research institutions, some having independent status, several museums, and other academic and cultural facilities. The University enrolls nearly 34,000 students (2000), more than two-thirds in undergraduate study. The academic staff numbers just over 800 engaged in teaching and research. The members of the Team of Advisors appreciate the privilege of visiting the University of Latvia, and are grateful to Rector Ivars Lacis and his colleagues for their extraordinary candor in our discussions, and their exceptional hospitality. 1 VAP Report——Riga, Latvia, April, 2001 The Advisors commend the Rector for the comprehensive preparation for the visit. -

UNIVERSITY of PRISHTINA the University-History

Welcome to the Republic of Kosova UNIVERSITY OF PRISHTINA The University-History • The University of Prishtina was founded by the Law on the Foundation of the University of Prishtina, which was passed by the Assembly of the Socialist Province of Kosova on 18 November 1969. • The foundation of the University of Prishtina was a historical event for Kosova’s population, and especially for the Albanian nation. The Foundation Assembly of the University of Prishtina was held on 13 February 1970. • Two days later, on 15 February 1970 the Ceremonial Meeting of the Assembly was held in which the 15 February was proclaimed The Day of the University of Prishtina. • The University of Prishtina (UP), similar to other universities in the world, conveys unique responsibilities in professional training and research guidance, which are determinant for the development of the industry and trade, infra-structure, and society. • UP has started in 2001 the reforming of all academic levels in accordance with the Bologna Declaration, aiming the integration into the European Higher Education System. Facts and Figures 17 Faculties Bachelor studies – 38533 students Master studies – 10047 students PhD studies – 152 students ____________________________ Total number of students: 48732 Total number of academic staff: 1021 Visiting professors: 885 Total number of teaching assistants: 396 Administrative staff: 399 Goals • Internationalization • Integration of Kosova HE in EU • Harmonization of study programmes of the Bologna Process • Full implementation of ECTS • Participation -

Andra Kalnača a Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar

Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Copyright © 2014 Andra Kalnača ISBN 978-3-11-041130-0 e- ISBN 978-3-11-041131-7 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Ieva Kalnača Contents Abbreviations I Introduction II 1 The Paradigmatics and Declension of Nouns 1 1.1 Introductory Remarks on Paradigmatics 1 1.2 Declension 4 1.2.1 Noun Forms and Palatalization 9 1.2.2 Nondeclinable Nouns 11 1.3 Case Syncretism 14 1.3.1 Instrumental 18 1.3.2 Vocative 25 1.4 Reflexive Nouns 34 1.5 Case Polyfunctionality and Case Alternation 47 1.6 Gender 66 2 The Paradigmatics and Conjugation of Verbs 74 2.1 Introductory Remarks 74 2.2 Conjugation 75 2.3 Tense 80 2.4 Person 83 3 Aspect 89 -

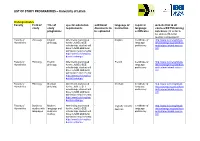

University of Latvia

LIST OF STUDY PROGRAMMES – University of Latvia Undergraduates Faculty Field of Title of special admission additional language of required website link to all study study requirements documents to instruction language courses/ECTS/learning programme be uploaded certificates outcomes (in order to be able to fill in the learning agreement) Faculty of Philology English After being nominated - English Certificate of http://www.lu.lv/eng/istude Humanities philology for the JoinEU-SEE language nts/exchange/courses/hum scholarship, student will proficiency anities/provisional-course- have to fulfill additional list/ admission requirements: http://www.lu.lv/eng/istu dents/exchange/ Faculty of Philology French After being nominated - French Certificate of http://www.lu.lv/eng/istude Humanities philology for the JoinEU-SEE language nts/exchange/courses/hum scholarship, student will proficiency anities/provisional-course- have to fulfill additional list/ admission requirements: http://www.lu.lv/eng/istu dents/exchange/ Faculty of Philology German After being nominated - German Certificate of http://www.lu.lv/eng/istude Humanities philology for the JoinEU-SEE language nts/exchange/courses/hum scholarship, student will proficiency anities/provisional-course- have to fulfill additional list/ admission requirements: http://www.lu.lv/eng/istu dents/exchange/ Faculty of Business Modern After being nominated - English/ French/ Certificate of http://www.lu.lv/eng/istude Humanities studies with language and for the JoinEU-SEE German language nts/exchange/courses/hum -

Language Attrition and Death: Livonian in Its Terminal Phase

1 Christopher Moseley LANGUAGE ATTRITION AND DEATH: LIVONIAN IN ITS TERMINAL PHASE Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London March 1993 ProQuest Number: 10046089 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10046089 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 INTRODUCTION This study of the present state of the Livonian language, a Baltic-Finnic tongue spoken by a few elderly people formerly resident in a dozen fishing villages on the coast of Latvia, consists of four main parts. Part One gives an outline of the known history of the Livonian language, the history of research into it, and of its own relations with its closest geographical neighbour, Latvian, a linguistically unrelated Indo-European language. A state of Latvian/Livonian bilingualism has existed for virtually all of the Livonians' (or Livs') recorded history, and certainly for the past two centuries. Part Two consists of a Descriptive Grammar of the present- day Livonian language as recorded in an extensive corpus provided by one speaker. -

Latgalian, a Short Grammar of (Nau).Pdf

Languages of the World/Materials 482 A short grammar of Latgal ian Nicole Nau full text research abstracts of all titles monthly updates 2011 LINCOM EUROPA LATGALIAN LW/M482 Published by LINCOM GmbH 2011. Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................ 3 LINCOMGmbH 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Gmunder Str. 35 J .1 General information .................................................................................................. 4 D-81379 Muenchen 1.2 History ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Research and description ........................................................................................... 7 [email protected] 1.4 Typological overview ................................................................................................ 8 www.lincom-europa.com 2. The sound system ..................................................................................................... 9 2. 1 Phonemes, sounds, and letters ................................................................................... 9 webshop: www.lincom-shop.eu 2.2 Stress and tone ......................................................................................................... 13 2.3 Phonological processes .......................................................................................... -

University of Latvia

UNIVERSITY OF LATVIA International Programmes 1 Rector’s Welcome On the verge of one hundred Established in 1919, the expand as new study infrastructure University of Latvia, the only classical will be built (Academic Centre for Social university in Latvia, has been a national Sciences and Humanities) as well as centre of higher education for almost facilities for scientific research and a century. Today it is a place where the technology transfer in the fields of life brightest academic minds, innovative science and nanotechnology. research and exciting study process meet. We are certain that the world class study and research process, the University of Latvia is increasing number of international continuously developing — expanding students and dynamic student life horizons of the academic work and enhanced by the outstanding beauty scientific research by collaborating of local environment and Riga city will internationally, increasing the number make your studies or research at the of international study programmes, University of Latvia an unforgettable strengthening its cooperation with experience and a great contribution to industrial partners. The newly built your future. Academic Centre for Natural Sciences has become an excellent environment Experience the University of Latvia! for research-based study process and multidisciplinary research opportunities. And this is only a Prof. Indriķis Muižnieks beginning. Within the years to come, Rector of the University of Latvia the University of Latvia campus will Full Member of the Latvian