Health Systems in Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 12, 1992 Prepared By: Clyde Hertzman MD

OM TRIP REPORT ON ENVIRONMENT & HEALTH IN THE BALTIC COUNTRIES January 11 - February 12, 1992 Prepared by: Clyde Hertzman MD, MSc, FRCPC WORLD ENVIRONMENT CENTER 419 Park Avenue South, Suite 1800 New York, NY 10016 May 1992 DISCLAIMER The opinions expressed herein are the professional opinions of the author and do not represent the official position of the Government of the United States or the World Environment Center. Environment and Health in the Faltic Countries by Clyde Hertzman MD, MSc, FRCPC My investigations into environmental health conditions in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were the first I conducted in republics of the former Soviet Union. In comparison to Poland. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria (herein, the non-Soviet republics or Central Europe) which 1previously investigated, they were notable for a general lack of useful data on the human health impact of environmental pollution. This difference could not be attributed to an absence of public health agencies similar to those found in the non- Soviet republics since, in a superficial sense, the institutional structures are quite similar all across Central and Eastern Europe. However, the Baltic republics seemed to have additional obstacles to the effective evaluation of environmental health problems not encountered in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria. In the Baltics, the agencies responsible for environmental measurement and public health investigation tended to have stronger reporting relationships with Moscow than with each other. This lead to alow degree of inter-agency co-operation and made the agencies susceptible to manipulation according to interests which conflicted with their (theoretical) mandate to protect the public's health. -

LONG-TERM CHANGES in the WATER TEMPERATURE of RIVERS in LATVIA Inese Latkovska1,2 # and Elga Apsîte1

PROCEEDINGS OF THE LATVIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES. Section B, Vol. 70 (2016), No. 2 (701), pp. 78–87. DOI: 10.1515/prolas-2016-0013 LONG-TERM CHANGES IN THE WATER TEMPERATURE OF RIVERS IN LATVIA Inese Latkovska1,2 # and Elga Apsîte1 1 Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Latvia, Jelgavas iela 1, Rîga LV-1004, LATVIA, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Latvian Environment, Geology, and Meteorology Centre, Maskavas iela 165, Rîga LV-1019, LATVIA # Corresponding author Communicated by Mâris Kïaviòð The study describes the trends of monthly mean water temperature (from May to October) and the annual maximum water temperature of the rivers in Latvia during the time period from 1945 to 2000. The results demonstrated that the mean water temperatures during the monitoring period from May to October were higher in the largest rivers (from 13.6 oC to 16.1 oC) compared to those in the smallest rivers (from 11.5 oC to 15.7 oC). Similar patterns were seen for the maxi- mum water temperature: in large rivers from 22.9 oC to 25.7 oC, and in small rivers from 20.8 oC to 25.8 oC. Generally, lower water temperatures occurred in rivers with a high groundwater inflow rate, for example, in rivers of the Gauja basin, in particular, in the Amata River. Mann-Kendall test results demonstrated that during the monitoring period from May to October, mean water tem- peratures had a positive trend. However, the annual maximum temperature had a negative trend. Key words: water temperature, long-term changes, river, Latvia. -

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

Youth Policies in Latvia

Youth Wiki national description Youth policies in Latvia 2019 The Youth Wiki is Europe's online encyclopaedia in the area of national youth policies. The platform is a comprehensive database of national structures, policies and actions supporting young people. For the updated version of this national description, please visit https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/en/youthwiki 1 Youth 2 Youth policies in Latvia – 2019 Youth Wiki Latvia ................................................................................................................. 7 1. Youth Policy Governance................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Target population of youth policy ............................................................................................. 9 1.2 National youth law .................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 National youth strategy ........................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Youth policy decision-making .................................................................................................. 12 1.5 Cross-sectoral approach with other ministries ....................................................................... 13 1.6 Evidence-based youth policy ................................................................................................... 14 1.7 Funding youth policy .............................................................................................................. -

World Bank Document

35846 v 1 Public Disclosure Authorized Assessing Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations Financing Higher Education Controlling Health Care Expenditures Managing Fiscal Risks in Public-Private Partnerships Public Disclosure Authorized VOLUME I: MAIN REPORT VOLUME II: COUNTRY CASE STUDIES (CD) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Contents FOREWORD ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Daniela Gressani CONTRIBUTORS ................................................................................................................................ 9 CONFERENCE AGENDA ...................................................................................................................... 10 OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Thomas Laursen I. FISCAL CHALLENGES FOR THE EU8 COUNTRIES ......................................................................... 27 Paulina Bucon and Emilia Skrok 1. FISCAL DEVELOPMENTS 1995-2004 ........................................................................................ 27 2. MEDIUM-LONG TERM FISCAL PROSPECTS ............................................................................... 43 3. QUALITY OF FISCAL POLICY ..................................................................................................... 46 II. INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL RELATIONS .............................................................................. -

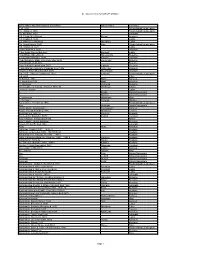

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

The Military Heritage and Environment of Kurzeme

SELFDRIVE THE MILITARY HERITAGE AND ENVIRONMENT OF KURZEME The NATURA 2000 system was established by European Union member states to protect a large series of environmental territories. In Latvia’s case, the system includes territories that were protected before it was set up, as well as 122 new territories. Each EU member state establishes its own system of territories, and these are then joined in the central system. NATURA 2000 territories are of European importance and are environmentally protected. Along this route, the most interesting NATURA 2000 territories include the Zvārde Forest Park, the Embūte Nature Park, the Ziemupe Nature Reserve and the Nature Park of the Ancient Abava River Valley. While in these territories, please be gentle with environmental, cultural and historical values. Keep the “interests” of birds in mind when birdwatching. ROUTE During the Soviet era, Latvia was the western border of the USSR, and that made it a strategic location in which lots of military resources were concentrated. During the Soviet occupation, there were more than 1,000 Soviet military units in Latvia, and they controlled some 600 facilities equalling to more than 10% of the territory of the Latvian SSR. In other words, Latvia was behind the Iron Curtain for nearly half a century. Border guard posts, tank bases, aviation bases, military airfields, storage facilities for weapons and munitions (including nuclear missiles), military espionage facilities and other, similar entities were mostly centred on the shore of the Baltic Sea, where there was a special frontier regime. It was just 20 years ago that people were allowed to be on the beach only during sunlight and in very limited areas. -

Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Interaction Development As Future for Rural Regions. Case Study of Aizkraukle Region in Latvia

Environmental and Climate Technologies 2019, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 129–146 doi: 10.2478/rtuect-2019-0084 https://content.sciendo.com Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Interaction Development as Future for Rural Regions. Case Study of Aizkraukle Region in Latvia Indra MUIZNIECE1*, Lauma ZIHARE2, Jelena PUBULE3, Dagnija BLUMBERGA4 1–4Institute of Energy Systems and Environment, Riga Technical University, Azenes iela 12/1, Riga, LV-1048, Latvia Abstract – In order to enforce the concepts of bioeconomy and the circular economy, the use of a bottom-up approach at the national level has been proposed: to start at the level of a small region, encourage its development, considering its specific capacities and resources, rather than applying generalized assumptions at a national or international level. Therefore, this study has been carried out with an aim to develop a methodology for the assessment of small rural areas in the context of the circular economy and bioeconomy, in order to advance the development of these regions in an effective way, using the existing bioresources comprehensively. The methodology is based on the identification of existing and potential bioeconomy flows (land and its use, bioresources, human resources, employment and business), the identification of the strengths of their interaction and compare these with the situation at the regional and national levels in order to identify the specific region's current situation in the bioeconomy and identify more forward-looking directions for development. Several methods are integrated and interlinked in the methodology – indicator analysis, correlation and regression analysis, and heat map tables. The methodology is approbated on one case study – Aizkraukle region – a small rural region in Latvia. -

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

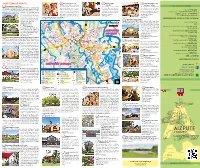

Sightseeing in Aizpute

SIGHTSEEING IN AIZPUTE 9 Valda Jēriņa Dolls room 14 Weavers’ Studio 20 Centre of workshops and The exposition shows a collection “Kamolītis” residences “SERDE” WWW.VISITAIZPUTE.LV 1 Livonian Order Castle Ruins of dolls created by national theatre The workshop offers its visitors This set of historical buildings, with th The Livonian Order built the fortifications in the 13 century. In the actress Valda Jēriņa. There are more to see the process of different its creative ambience, welcomes – 113, 112 113, – Ambulance th 15 century, a residential house was built at its eastern wall, with than 500 thematically dressed dolls canvas being woven in the looms you to enjoy a variety of cultural – (+371) 26475143 (+371) – police municipal county Aizpute cellars and a gallery; thus the fortifications were turned into a castle. in the collection: dolls in national according to ancient methods tourism opportunities, art and – 110, 112, (+371) 63448192 (+371) 112, 110, – It served as a border fortification at police State costumes, school uniforms, theatrical and using traditional ornaments. cultural events (open in summer). the cross point of the territories of – 112 – and fantasy costumes. There is a Katoļu iela 1, Aizpute, Atmodas iela 9, Aizpute, departament Rescue and Fire the Livonian Order and the Bishop children’s playroom next to the (+371) 22847115 (+371) 29817180, of Courland (Latvian: Kurzeme). exhibition halls. Book your visit in advance. www.serde.lv EMERGENCY OF CASES IN CALL TO WHERE The river Tebra was the border: the Katoļu iela 1, Aizpute, (+371) 28617307 Bishopric on the right bank and the 21 “IDEJU MĀJA” (IDEA HOUSE) (+371) 25125190 (+371) Phone: Livonian Order on the left. -

Latvia Towards Europe: Internal Security Issues

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Andris Runcis LATVIA TOWARDS EUROPE: INTERNAL SECURITY ISSUES Final Report The preparation of this Report was made possible through a NATO Award. Rîga, 1999 1 Content Introduction 3 1. The basic aspects of a country’s security 5 2. Latvia’s security concept 8 3. Corruption 10 4. Unemployment 17 5. Non-governmental organizations 19 6. The Latvian banking system and its crisis 27 7. Citizenship issue 32 Conclusion 46 Appendix 48 2 Introduction The security of small countries has been a difficult problem since ancient times. Now, when the Cold War has ended and Europe has moved from a bipolar to a multipolar system, when the communist system in Eastern Europe has collapsed and the Soviet empire has disintegrated – processes which have led to the appearance of a series of new and mostly small countries in Europe – we are witnessing a renaissance of small countries in the international arena. Since regaining independence Latvia’s general foreign policy orientation has been associated with integration into European economic, political and military structures where full membership in the European Union (EU) is the cornerstone. The issue has been one of the most consolidated and undisputed on the country’s political agenda. Latvian politicians have stressed the country’s wish to become a member state of the European Union. On October 14, 1995, all political parties represented in the Parliament supported the State President’s proposed Declaration on the Policy of Latvian Integration in the European Union. On October 27, Latvia submitted its application for membership to the EU. -

AS "Moda Kapitāls" Annual Report for the Year 2020

AS "Moda Kapitāls” ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2020 prepared in accordance with IFRS us adopted in EU Riga, 29th April, 2021 AS "Moda Kapitāls" Annual report for the year 2020. Prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards as adopted in EU AS "Moda Kapitāls” ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2020 prepared in accordance with IFRS us adopted in EU CONTENT Page General information 3 Management report 4 Statement of management responsibility 5 Financial statements: Statement of comprehensive income 6 Statement of financial position 7 Cash flow statement 8 Statement of changes in equity 9 Notes 10 Independent auditors' report 27 2 AS "Moda Kapitāls” ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2020 prepared in accordance with IFRS us adopted in EU GERNERAL INFORMATION Name of the company Moda Kapitāls Legal status of the company Joint Stock Company Registration number, place and date of registration LV 40003345861, Riga, June 9, 1997 Registered office Ganību dambis 40A-34, Rīga, LV-1005 Shareholders Andris Banders (24.76%), Tvinger SIA (20%), Ilvars Sirmais (16.14%), MK Investīcijas, SIA (14.75%), Verners Skrastiņš (14.05%), Guntars Zvīnis (10.29%) Board Members Guntars Zvīnisas of 23.04.2021 Ilvars Sirmais (till 05.08.2020) Edgars Bilinskis (5.08.2020.-24.11.2020) Marts Zeltiņš (16.12.2020-31.03.2021) Supervisory Board Members Marts Zeltiņš - head of the Council as of 23.04.2021 Andris Banders - deputy of the head of the Council Andris Blaka - member of the Council as of 06.11.2020 Inese Kanneniece - meber of the Council Ilvars Sirmais - member of the Council as of 6.11.2020 Guntars Zvīnis - member of the Council (6.11.2021-22.04.2021) Verners Skrastiņš - head of the Council till 6.11.2020 Diāna Zvīne - member of the Council till 6.11.2020 Ilze Sirmā - member of the Council till 6.11.2020 Financial year from 01.01.2020 to 31.12.2020 Currency used in the financial statements EUR Details of related companies: AUREUM AS, legal address: Peldu Street 6, Liepāja, participation share - 100%.