Declension of Nouns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

On Root Modality and Thematic Relations in Tagalog and English*

Proceedings of SALT 26: 775–794, 2016 On root modality and thematic relations in Tagalog and English* Maayan Abenina-Adar Nikos Angelopoulos UCLA UCLA Abstract The literature on modality discusses how context and grammar interact to produce different flavors of necessity primarily in connection with functional modals e.g., English auxiliaries. In contrast, the grammatical properties of lexical modals (i.e., thematic verbs) are less understood. In this paper, we use the Tagalog necessity modal kailangan and English need as a case study in the syntax-semantics of lexical modals. Kailangan and need enter two structures, which we call ‘thematic’ and ‘impersonal’. We show that when they establish a thematic dependency with a subject, they express necessity in light of this subject’s priorities, and in the absence of an overt thematic subject, they express necessity in light of priorities endorsed by the speaker. To account for this, we propose a single lexical entry for kailangan / need that uniformly selects for a ‘needer’ argument. In thematic constructions, the needer is the overt subject, and in impersonal constructions, it is an implicit speaker-bound pronoun. Keywords: modality, thematic relations, Tagalog, syntax-semantics interface 1 Introduction In this paper, we observe that English need and its Tagalog counterpart, kailangan, express two different types of necessity depending on the syntactic structure they enter. We show that thematic constructions like (1) express necessities in light of priorities of the thematic subject, i.e., John, whereas impersonal constructions like (2) express necessities in light of priorities of the speaker. (1) John needs there to be food left over. -

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

Grammatical Gender and Grammatical Stems

Grammatical gender and grammatical stems How many grammatical genders exist in Czech? How can we tell the grammatical gender of a noun? What is a grammatical stem and how do we determine it? Why is knowing the grammatical stem important? How does the ending of a noun help us to know whether it is a hard- or soft-stem noun? Like other European languages (German, French, Spanish) but unlike English, Czech nouns are marked for grammatical gender. Czech has three grammatical genders: Masculine (M), Feminine (F), and Neuter (N). M and F partly overlap with the natural gender of human beings, so we have učitel for a male teacher and učitelka for a female teacher, sportovec for a male athlete and sportovkyně for a female athlete… But grammatical gender is a feature of all nouns (names of inanimate things, places, abstractions…), and it plays an important role in how Czech grammar works. To determine the grammatical gender of a noun (Maskulinum, femininum nebo neutrum?), we look at the ending—the last consonant or vowel—of the word in the Nominative singular (the basic or dictionary form of the word). 1. The great majority of nouns that end in a consonant are Masculine: profesor (professor), hrad (castle), stůl (table), pes (dog), autobus (bus), počítač (computer), čaj (tea), sešit (workbook), mobil (cell-phone)… Masculine nouns can be further divided into animate nouns (people and animals) and inanimate nouns (things, places, abstractions). 2. The great majority of nouns that end in -a are Feminine: profesorka (professor), lampa (lamp), kočka (cat), kniha (book), ryba (fish), fotka (photo), třída (classroom), podlaha (floor), budova (building)… 3. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

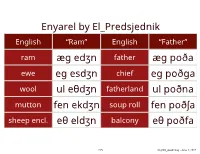

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 |

Edmonds CC Writing Center | MUK 113 Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 | www.edcc.edu/lsc FINDING AND FIXING APOSTROPHE ERRORS What is an Apostrophe Error? Apostrophes are used to show ownership and are used to show that one or more letters are missing in a contraction. An apostrophe error occurs when an apostrophe is needed to show possession or contraction, but it is not there or is in the wrong place. Apostrophes have two main uses: contractions and possession. If you can learn these rules, you can master apostrophe usage! Contractions: Contractions are shortened forms of words which add an informal tone to academic writing. An apostrophe indicates that one or more letters have been left out. To assess whether you need an apostrophe or not, re-read the sentence to see if you can expand the shortened contraction words by filling in the missing letters. Place an apostrophe where letters are missing. Thao wasn’t in class today. (The apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter “o”). Thao was not in class today. (Note that you can expand the shortened word “wasn’t” by just filling in the missing letter “o”). These are some of the most common contractions: I am = I’m It is = It’s Who is = Who’s She is = She’s She would = She’d She would have = She would’ve He is = He’s He would = He’d He would have = He would’ve Let us = Let’s You are = You’re They had = They’d When to Use It’s vs. -

The “Person” Category in the Zamuco Languages. a Diachronic Perspective

On rare typological features of the Zamucoan languages, in the framework of the Chaco linguistic area Pier Marco Bertinetto Luca Ciucci Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa The Zamucoan family Ayoreo ca. 4500 speakers Old Zamuco (a.k.a. Ancient Zamuco) spoken in the XVIII century, extinct Chamacoco (Ɨbɨtoso, Tomarâho) ca. 1800 speakers The Zamucoan family The first stable contact with Zamucoan populations took place in the early 18th century in the reduction of San Ignacio de Samuco. The Jesuit Ignace Chomé wrote a grammar of Old Zamuco (Arte de la lengua zamuca). The Chamacoco established friendly relationships by the end of the 19th century. The Ayoreos surrended rather late (towards the middle of the last century); there are still a few nomadic small bands in Northern Paraguay. The Zamucoan family Main typological features -Fusional structure -Word order features: - SVO - Genitive+Noun - Noun + Adjective Zamucoan typologically rare features Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition All Zamucoan languages present a morphological tripartition in their nominals. The base-form (BF) is typically used for predication. The singular-BF is (Ayoreo & Old Zamuco) or used to be (Cham.) the basis for any morphological operation. The full-form (FF) occurs in argumental position. -

Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject-Sharing and Index-Sharing

Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject-Sharing and Index-Sharing Juwon Lee The University of Texas at Austin Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar University at Buffalo Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2014 CSLI Publications pages 135–155 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2014 Lee, Juwon. 2014. Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject- Sharing and Index-Sharing. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 21st In- ternational Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, University at Buffalo, 135–155. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract In this paper I present an account for the lexical passive Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) in Korean. Regarding the issue of how the arguments of an SVC are realized, I propose two hypotheses: i) Korean SVCs are broadly classified into two types, subject-sharing SVCs where the subject is structure-shared by the verbs and index- sharing SVCs where only indices of semantic arguments are structure-shared by the verbs, and ii) a semantic argument sharing is a general requirement of SVCs in Korean. I also argue that an argument composition analysis can accommodate such the new data as the lexical passive SVCs in a simple manner compared to other alternative derivational analyses. 1. Introduction* Serial verb construction (SVC) is a structure consisting of more than two component verbs but denotes what is conceptualized as a single event, and it is an important part of the study of complex predicates. A central issue of SVC is how the arguments of the component verbs of an SVC are realized in a sentence.