Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

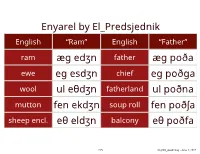

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

Andra Kalnača a Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar

Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Copyright © 2014 Andra Kalnača ISBN 978-3-11-041130-0 e- ISBN 978-3-11-041131-7 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Ieva Kalnača Contents Abbreviations I Introduction II 1 The Paradigmatics and Declension of Nouns 1 1.1 Introductory Remarks on Paradigmatics 1 1.2 Declension 4 1.2.1 Noun Forms and Palatalization 9 1.2.2 Nondeclinable Nouns 11 1.3 Case Syncretism 14 1.3.1 Instrumental 18 1.3.2 Vocative 25 1.4 Reflexive Nouns 34 1.5 Case Polyfunctionality and Case Alternation 47 1.6 Gender 66 2 The Paradigmatics and Conjugation of Verbs 74 2.1 Introductory Remarks 74 2.2 Conjugation 75 2.3 Tense 80 2.4 Person 83 3 Aspect 89 -

Declension of Nouns

DECLENSION OF NOUNS In English, the relationship between words in a sentence depends primarily on word order. The difference between the god desires the girl and the girl desires the god is immediately apparent to us. Latin does not depend on word order for basic meaning, but on inflections (changes in the endings of words) to indicate the function of words within a sentence. Thus the god desires the girl can be expressed in Latin deus puellam desiderat, puellam deus desiderat, or desiderat puellam deus without any change in basic meaning. The accusative ending of puellam shows that the girl is being acted upon (i.e., is the object of the verb) and is not the actor (i.e., the subject of the verb). Similarly, the nominative form of deus shows that the god is the actor (agent) in the sentence, not the object of the verb. The inflection of nouns is called declension. The individual declensions are called cases, and together they form the case system. Nouns, pronouns, adjectives and participles are declined in six Cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and vocative and two Numbers (singular and plural). (The locative, an archaic case, existed in the classical period only for a few words). Nominative Indicates the subject of a sentence. (The boy loves the book). Genitive Indicates possession. (The boy loves the girl’s book). Dative Indicates indirect object. (The boy gave the book to the girl). Accusative Indicates direct object. (The boy loves the book). Ablative Answers the questions from where? by what means? how? from what cause? in what manner? when? or where? The ablative is used to show separation (from), instrumentality or means (by, with), accompaniment (with), or locality (at). -

The Distribution of Definiteness Markers and the Growth of Syntactic Structure from Old Norse to Modern Faroese

The Distribution of Definiteness Markers and the Growth of Syntactic Structure from Old Norse to Modern Faroese. A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 Pauline Harries School of Arts, Languages and Cultures List of Contents 1. Introduction 10 1.1 Aims and scope of the thesis 10 1.2 Background to Faroese 11 1.3 Introduction to the Insular Scandinavian 12 1.3.1 Ancestry and development 12 1.3.2 Faroese as an Insular Scandinavian language 14 1.3.3 The Noun Phrase in Faroese 18 1.4 Introduction to LFG 20 2. Definiteness Marking in Old Norse 23 2.1 Introduction 23 2.2 Previous literature on Old Norse 24 2.2.1 Descriptive literature 24 2.2.2 Theoretical literature 28 2.2.3 Origins of hinn 32 2.3 Presentation of Data 33 2.3.1 Zero definite marking 33 2.3.2 The hinn paradigm 37 2.3.2.1 The bound definite marker 37 2.3.2.2 The free definite marker 39 2.3.2.3 The other hinn 43 2.3.3 Demonstratives 44 2.3.3.1 Relative Clauses 48 2.3.4 Adjectival marking of definiteness 49 2.3.4.1 Definite adjectives in Indo-European 50 2.3.4.2 Definite adjectives in Old Norse 53 2.3.4.3 The meaning of weak versus strong 56 2.3.5 Summary of Findings 57 2.4 Summary and discussion of Old Norse NP 58 2.4.1 Overview of previous literature 59 2.4.2 Feature Distribution and NP structure 60 2.5 Summary of Chapter 66 3. -

Negation, Referentiality and Boundedness In

WECATfON, REFERENTLALm ANT) BOUNDEDNESS flV BRETON A CASE STUDY Dl MARKEDNESS ANI) ASYMMETRY Nathalie Simone rMarie Schapansky B.A. (French), %=on Fraser University 1990 M.A. (Linguistics), Simon Fraser university 1992 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIEiEMEN'I'S FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Linguistics @Nathalie Simone Marie Schapansky, 1996 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY November 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. BibiiotMque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliogra~hicServices Branch des services bibiiographiques Your hie Vorre rbference Our hle Notre r6Orence The author has granted an k'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable nsn-exclusive f icence irtct5vocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of perrnettant a la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, prgttor, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque rnaniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes interessees. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial these. Ni la these ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent &re imprimes ou his/her permission. -

Anthropocentrism, Egocentrism and the Notion of Animacy Hierarchy Sandrine Sorlin, Laure Gardelle

Anthropocentrism, egocentrism and the notion of Animacy Hierarchy Sandrine Sorlin, Laure Gardelle To cite this version: Sandrine Sorlin, Laure Gardelle. Anthropocentrism, egocentrism and the notion of Animacy Hierarchy. International Journal of Language and Culture, John Benjamins Publishing, 2018, From Culture to Language and Back: The Animacy Hierarchy in language and discourse, 5 (2), 10.1075/ijolc.00004.gar. hal-01874511 HAL Id: hal-01874511 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01874511 Submitted on 5 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. (Introductory chapter) Anthropocentrism, egocentrism and the notion of Animacy Hierarchy Laure Gardelle, Université Grenoble-Alpes, LIDILEM Sandrine Sorlin, Aix Marseille Univ, LERMA, Aix-en-Provence, France Languages tend to exhibit different treatments of the entities of the extralinguistic world, with phrases that denote human beings (or more generally animates) at the top and phrases that denote inanimates at the bottom. This ranking is known as the Animacy Hierarchy. Croft (2003: 128) terms it one of the ‘best known grammatical hierarchies’, and the notion is so crucially important that it has made its way into the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Linguistics (Matthews 2007) or the Oxford English Dictionary (2017). -

Evidence from Evidentials

UBCWPL University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics Evidence from Evidentials Edited by: Tyler Peterson and Uli Sauerland September 2010 Volume 28 ii Evidence from Evidentials Edited by: Tyler Peterson and Uli Sauerland The University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 28 September 2010 UBCWPL is published by the graduate students of the University of British Columbia. We feature current research on language and linguistics by students and faculty of the department, and we are the regular publishers of two conference proceedings: the Workshop on Structure and Constituency in Languages of the Americas (WSCLA) and the International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages (ICSNL). If you have any comments or suggestions, or would like to place orders, please contact : UBCWPL Editors Department of Linguistics Totem Field Studios 2613 West Mall V6T 1Z4 Tel: 604 822 4256 Fax 604 822 9687 E-mail: <[email protected]> Since articles in UBCWPL are works in progress, their publication elsewhere is not precluded. All rights remain with the authors. iii Cover artwork by Lester Ned Jr. Contact: Ancestral Native Art Creations 10704 #9 Highway Compt. 376 Rosedale, BC V0X 1X0 Phone: (604) 793-5306 Fax: (604) 794-3217 Email: [email protected] iv TABLE OF CONTENTS TYLER PETERSON, ROSE-MARIE DÉCHAINE, AND ULI SAUERLAND ...............................1 Evidence from Evidentials: Introduction JASON BROWN ................................................................................................................9 -

Definiteness in a Language Without Articles – a Study on Polish

Definiteness in a Language without Articles – A Study on Polish Adrian Czardybon Hana Filip, Peter Indefrey, Laura Kallmeyer, Sebastian Löbner, Gerhard Schurz & Robert D. Van Valin, Jr. (eds.) Dissertations in Language and Cognition 3 Adrian Czardybon 2017 Definiteness in a Language without Articles – A Study on Polish BibliograVsche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen NationalbibliograVe; detaillierte bibliograVsche Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. D 61 © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2017 http://www.dupress.de Einbandgestaltung: Doris Gerland, Christian Horn, Albert Ortmann Satz: Adrian Czardybon, Thomas Gamerschlag Herstellung: docupoint GmbH, Barleben Gesetzt aus der Linux Libertine ISBN 978-3-95758-047-4 Für meine Familie Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Theoretical basis 9 2.1 The distribution of the definite article in English and German . 9 2.2 Approaches to definiteness . 13 2.2.1 Familiarity . 13 2.2.2 Uniqueness . 16 2.3 Löbner’s approach to definiteness . 18 2.3.1 Inherent uniqueness and inherent relationality . 18 2.3.2 Concept types . 19 2.3.3 Shifts and determination . 20 2.3.4 Semantic vs. pragmatic uniqueness . 22 2.3.5 Scale of uniqueness . 25 2.4 Mass/count distinction . 30 2.5 Definiteness strategies discussed in the Slavistic literature . 35 3 Demonstratives 43 3.1 Criteria for the grammaticalization of definite articles . 44 3.2 Polish determiners and the paradigm of ten . 46 3.3 Previous studies on demonstratives in Polish . 49 3.4 My analysis of ten . 55 3.4.1 The occurrence of ten with pragmatic uniqueness . -

5. Declension of Nouns

Kolumnentitel 91 5. DECLENSION OF NOUNS 5.1. Declensional Classes of Noun in Modern Lithuanian 5.1.1. Lithuanian noun infl ection has not been the subject of recent studies. There is no fi xed classifi cation for Lithuanian noun classes. The main grammars and other studies neither agree on the number of classes nor on the criteria to be used for establishing these classes. There are fi ve classes of nouns in Standard Modern Lithuanian (SML): (i)a, (i)u, (i)o, ė and i. Grouping of nouns into these classes is determined by the infl ec- tional stem of the noun. The class that a noun belongs to is brought out by characteristic endings in the nominative singular, and especially in the dative plural. Within each class it is possible to distinguish a set of specifi c endings which fall under different paradigms, the total number of which is twelve (cf. Ambrazas et al. 1997). It should be noted in this connection that classifi cation of nouns into the fi ve classes according to the infl ectional stem as proposed in A grammar of modern Lithuanian corre- sponds to the traditional classes usually referred to by numbers. The system of paradigms can thus be treated as a more convenient method used for displaying the distribution of nouns according to gender distinctions. 5.1.2. In this study we will introduce a classifi cation of noun classes which differs from the traditional one (cf. 5.1.1) and assume Dressler’s following concepts and defi nitions (Dressler et al.