Grammatical Gender and Declension Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

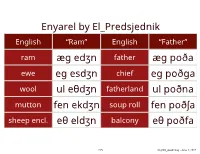

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Grammatical Gender in the German Multiethnolect Peter Auer & Vanessa Siegel

1 Grammatical gender in the German multiethnolect Peter Auer & Vanessa Siegel Contact: Deutsches Seminar, Universität Freiburg, D-79089 Freiburg [email protected], [email protected] Abstract While major restructurations and simplifications have been reported for gender systems of other Germanic languages in multiethnolectal speech, the article demonstrates that the three-fold gender distinction of German is relatively stable among young speakers of immigrant background. We inves- tigate gender in a German multiethnolect, based on a corpus of appr. 17 hours of spontaneous speech by 28 young speakers in Stuttgart (mainly of Turkish and Balkan backgrounds). German is not their second language, but (one of) their first language(s), which they have fully acquired from child- hood. We show that the gender system does not show signs of reduction in the direction of a two gender system, nor of wholesale loss. We also argue that the position of gender in the grammar is weakened by independent processes, such as the frequent use of bare nouns determiners in grammatical contexts where German requires it. Another phenomenon that weakens the position of gender is the simplification of adjective/noun agreement and the emergence of a generalized, gender-neutral suffix for pre-nominal adjectives (i.e. schwa). The disappearance of gender/case marking in the adjective means that the grammatical cat- egory of gender is lost in A + N phrases (without determiner). 1. Introduction Modern German differs from most other Germanic languages -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

Measuring the Similarity of Grammatical Gender Systems by Comparing Partitions

Measuring the Similarity of Grammatical Gender Systems by Comparing Partitions Arya D. McCarthy Adina Williams Shijia Liu David Yarowsky Ryan Cotterell Johns Hopkins University, Facebook AI Research, ETH Zurich [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract A grammatical gender system divides a lex- icon into a small number of relatively fixed grammatical categories. How similar are these gender systems across languages? To quantify the similarity, we define gender systems ex- (a) German, K = 3 (b) Spanish, K = 2 tensionally, thereby reducing the problem of comparisons between languages’ gender sys- Figure 1: Two gender systems partitioning N = 6 con- tems to cluster evaluation. We borrow a rich cepts. German (a) has three communities: Obst (fruit) inventory of statistical tools for cluster evalu- and Gras (grass) are neuter, Mond (moon) and Baum ation from the field of community detection (tree) are masculine, Blume (flower) and Sonne (sun) (Driver and Kroeber, 1932; Cattell, 1945), that are feminine. Spanish (b) has two communities: fruta enable us to craft novel information-theoretic (fruit), luna (moon), and flor are feminine, and cesped metrics for measuring similarity between gen- (grass), arbol (tree), and sol (sun) are masculine. der systems. We first validate our metrics, then use them to measure gender system similarity in 20 languages. Finally, we ask whether our exhaustively divides up the language’s nouns; that gender system similarities alone are sufficient is, the union of gender categories is the entire to reconstruct historical relationships between languages. Towards this end, we make phylo- nominal lexicon. -

Andra Kalnača a Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar

Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Copyright © 2014 Andra Kalnača ISBN 978-3-11-041130-0 e- ISBN 978-3-11-041131-7 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Ieva Kalnača Contents Abbreviations I Introduction II 1 The Paradigmatics and Declension of Nouns 1 1.1 Introductory Remarks on Paradigmatics 1 1.2 Declension 4 1.2.1 Noun Forms and Palatalization 9 1.2.2 Nondeclinable Nouns 11 1.3 Case Syncretism 14 1.3.1 Instrumental 18 1.3.2 Vocative 25 1.4 Reflexive Nouns 34 1.5 Case Polyfunctionality and Case Alternation 47 1.6 Gender 66 2 The Paradigmatics and Conjugation of Verbs 74 2.1 Introductory Remarks 74 2.2 Conjugation 75 2.3 Tense 80 2.4 Person 83 3 Aspect 89 -

Extending Research on the Influence of Grammatical Gender on Object

doi:10.5128/ERYa13.14 extending reSearCh on the influenCe of grammatiCal gender on objeCt ClaSSifiCation: a CroSS-linguiStiC Study Comparing eStonian, italian and lithuanian native SpeakerS Luca Vernich, Reili Argus, Laura Kamandulytė-Merfeldienė Abstract. Using different experimental tasks, researchers have pointed 13, 223–240 EESTI RAKENDUSLINGVISTIKA ÜHINGU AASTARAAMAT to a possible correlation between grammatical gender and classification behaviour. Such effects, however, have been found comparing speakers of a relatively small set of languages. Therefore, it’s not clear whether evidence gathered can be generalized and extended to languages that are typologically different from those studied so far. To the best of our knowledge, Baltic and Finno-Ugric languages have never been exam- ined in this respect. While most previous studies have used English as an example of gender-free languages, we chose Estonian because – contrary to English and like all Finno-Ugric languages – it does not use gendered pronouns (‘he’ vs. ‘she’) and is therefore more suitable as a baseline. We chose Lithuanian because the gender system of Baltic languages is interestingly different from the system of Romance and German languages tested so far. Taken together, our results support and extend previous findings and suggest that they are not restricted to a small group of languages. Keywords: grammatical gender, categorization, object classification, language & cognition, linguistic relativity, Estonian, Lithuanian, Italian 1. Introduction Research done in recent years suggests that our native language can affect non-verbal cognition and interfere with a variety of tasks. Taken together, psycholinguistic evidence points to a possible correlation between subjects’ behaviour in laboratory settings and certain lexical or morphological features of their native language. -

Declension of Nouns

DECLENSION OF NOUNS In English, the relationship between words in a sentence depends primarily on word order. The difference between the god desires the girl and the girl desires the god is immediately apparent to us. Latin does not depend on word order for basic meaning, but on inflections (changes in the endings of words) to indicate the function of words within a sentence. Thus the god desires the girl can be expressed in Latin deus puellam desiderat, puellam deus desiderat, or desiderat puellam deus without any change in basic meaning. The accusative ending of puellam shows that the girl is being acted upon (i.e., is the object of the verb) and is not the actor (i.e., the subject of the verb). Similarly, the nominative form of deus shows that the god is the actor (agent) in the sentence, not the object of the verb. The inflection of nouns is called declension. The individual declensions are called cases, and together they form the case system. Nouns, pronouns, adjectives and participles are declined in six Cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and vocative and two Numbers (singular and plural). (The locative, an archaic case, existed in the classical period only for a few words). Nominative Indicates the subject of a sentence. (The boy loves the book). Genitive Indicates possession. (The boy loves the girl’s book). Dative Indicates indirect object. (The boy gave the book to the girl). Accusative Indicates direct object. (The boy loves the book). Ablative Answers the questions from where? by what means? how? from what cause? in what manner? when? or where? The ablative is used to show separation (from), instrumentality or means (by, with), accompaniment (with), or locality (at). -

Chapter 3: Gender in Amharic Nominals

Page 1 of 31 CHAPTER 3: GENDER IN AMHARIC NOMINALS 1 INTRODUCTION Partially in preparation for the study of gender agreement in Chapter X, in this chapter I examine the gender system of Amharic nominals. I show how natural gender (aka semantic or biological gender, or sex) and grammatical gender (e.g., the arbitrary gender on inanimate objects) both must be part of the analysis of the Amharic gender system, and use Distributed Morphology assumptions about word formation to capture the distinction in a novel way. In Section 2, the main descriptive facts about gender in Amharic are presented. In Sections 3 and 4, I investigate where gender features are located within DPs in Amharic, arguing that natural gender (aka semantic or biological gender) is part of the feature bundle associated with the nominalizing head n, whereas grammatical gender is a diacritic feature on roots. In Section 4, I develop an analysis of gender using licensing conditions that predicts which of the two sources for gender are used for agreement. Previous analyses of gender and the broader implications of the analysis here are discussed in Section 5. Section 6 concludes. 2 GENDER IN NOMINALS As mentioned in Chapter 1, Amharic has two genders: masculine and feminine. The Amharic system for assigning gender is more reliant on natural gender (also called semantic or biological gender) than many of the more widely-known gender assignment systems (e.g., Spanish, French, Italian, Greek, etc.). For example, there is not a more or less equal division of the set of inanimate nouns into masculine and feminine. -

Grammatical Gender and Linguistic Complexity

Grammatical gender and linguistic complexity Volume I: General issues and specific studies Edited by Francesca Di Garbo Bruno Olsson Bernhard Wälchli language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 26 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J. (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. 17. Stenzel, Kristine & Bruna Franchetto (eds.). On this and other worlds: Voices from Amazonia. 18. Paggio, Patrizia and Albert Gatt (eds.). The languages of Malta. 19. Seržant, Ilja A. & Alena Witzlack-Makarevich (eds.). Diachrony of differential argument marking. 20. Hölzl, Andreas. A typology of questions in Northeast Asia and beyond: An ecological perspective. 21. Riesberg, Sonja, Asako Shiohara & Atsuko Utsumi (eds.). Perspectives on information structure in Austronesian languages.