Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

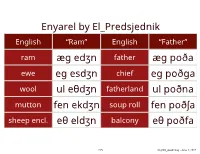

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

Animacy Encoding in English: Why and How

Animacy Encoding in English: why and how Annie Zaenen Jean Carletta Gregory Garretson PARC & Stanford University HCRC-University of Edinburgh Boston University 3333 Coyote Hill Road 2, Buccleuch Place Program in Applied Linguistics Palo Alto, CA 94304] Edinburgh EH8LW, UK 96 Cummington St., [email protected] [email protected] Boston, MA 02215 [email protected] Joan Bresnan Andrew Koontz-Garboden Tatiana Nikitina CSLI-Stanford University CSLI-Stanford University CSLI-Stanford University 220, Panama Street 220, Panama Street 220, Panama Street Stanford CA 94305 Stanford CA 94305 Stanford CA 94305 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] M. Catherine O’Connor Tom Wasow Boston University CSLI-Stanford University Program in Applied Linguistics 220, Panama Street 96 Cummington St., Stanford CA 94305 Boston, MA 02215 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract of entity representation within language: the definiteness dimension is linked to the status of the We report on two recent medium-scale initiatives entity at a particular point in the discourse, the annotating present day English corpora for animacy person hierarchy depends on the participants distinctions. We discuss the relevance of animacy for within the discourse, and the animacy status is an computational linguistics, specifically generation, the annotation categories used in the two studies and the inherent characteristic of the entities referred to. interannotator reliability for one of the studies. Each of these aspects, however, orders entities on a scale that makes them more or less salient or 1 Introduction ‘accessible’ when humans use their language. It has long been known that animacy is an The importance of accessibility scales is not important category in syntactic and morphological widely recognized in computational treatments of natural language analysis. -

4.1 Inflection

4.1 Inflection Within a lexeme-based theory of morphology, the difference between derivation and inflection is very simple. Derivation gives you new lexemes, and inflection gives you the forms of a lexeme that are determined by syntactic environment (cf. 2.1.2). But what exactly does this mean? Is there really a need for such a distinction? This section explores the answers to these questions, and in the process, goes deeper into the relation between morphology and syntax. 4.1.1 Inflection vs. derivation The first question we can ask about the distinction between inflection and derivation is whether there is any formal basis for distinguishing the two: can we tell them apart because they do different things to words? One generalization that has been made is that derivational affixes tend to occur closer to the root or stem than inflectional affixes. For example, (1) shows that the English third person singular present inflectional suffix -s occurs outside of derivational suffixes like the deadjectival -ize, and the plural ending -s follows derivational affixes including the deverbal -al: (1) a. popular-ize-s commercial-ize-s b. upheav-al-s arriv-al-s Similarly, Japanese derivational suffixes like passive -rare or causative -sase precede inflectional suffixes marking tense and aspect:1 (2) a. tabe-ru tabe-ta eat- IMP eat- PERF INFLECTION 113 ‘eats’ ‘ate’ b. tabe-rare- ru tabe-rare- ta eat - PASS-IMP eat- PASS-PERF ‘is eaten’ ‘was eaten’ c. tabe-sase- ru tabe-sase- ta eat- CAUS-IMP eat- CAUS-PERF ‘makes eat’ ‘made eat’ It is also the case that inflectional morphology does not change the meaning or grammatical category of the word that it applies to. -

The Formation of the Fifth Declension; Uses of the Ablative Case; and at the End of the Lesson We'll Review the Vocabulary Which You Should Memorize in This Chapter

Chapter 22: Fifth Declension. Chapter 22 covers the following: the formation of the fifth declension; uses of the ablative case; and at the end of the lesson we'll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There is one important rule to remember in this chapter: fifth declension represents e-stem nouns which are for the most part feminine in gender. Fifth Declension. Hooray, hooray! Latin only has five declensions, so this is the last declension we'll study. Once you've mastered fifth declension, you've learned everything you need to know about Latin nouns in this class. Fifth declension consists of nouns characterized by -ē. This declension is a unique concoction which the Romans brewed up at one point in their history and which did not survive long. As Latin after classical antiquity began evolving into the various Romance languages, this e-stem category of nouns was conflated into other declensions and disappeared as a separate grammatical category. Here are the endings for fifth-declension nouns. Let's recite them together: -es, -ei, -ei, -em, -e; -es, -erum, -ebus, -es, -ebus. Note the dominance of -e- (often -ē-) which is, without doubt, the most significant feature of this declension, though the -ē- produces no mandatory long marks, meaning no forms are distinguished by macrons in this declension. A close look at the endings shows why it was easy for the post-classical Romans to subsume fifth declension into third, for instance. Fifth and third look a lot like each other. In fact, the majority of fifth-declension endings look like a long ē-stem with third-declension endings appended on to it. -

Number Systems in Grammar Position Paper

1 Language and Culture Research Centre: 2018 Workshop Number systems in grammar - position paper Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald I Introduction I 2 The meanings of nominal number 2 3 Special number distinctions in personal pronouns 8 4 Number on verbs 9 5 The realisation of number 12 5.1 The forms 12 5.2 The loci: where number is shown 12 5.3 Optional and obligatory number marking 14 5.4 The limits of number 15 5.4.1 Number and the meanings of nouns 15 5.4.2 'Minor' numbers 16 5.4.3 The limits of number: nouns with defective number values 16 6 Number and noun categorisation 17 7 Markedness 18 8 Split, or mixed, number systems 19 9 Number and social deixis 19 10 Expressing number through other means 20 11 Number systems in language history 20 12 Summary 21 Further readings 22 Abbreviations 23 References 23 1 Introduction Every language has some means of distinguishing reference to one individual from reference to more than one. Number reference can be coded through lexical modifiers (including quantifiers of various sorts or number words etc.), or through a grammatical system. Number is a referential property of an argument of the predicate. A grammatical system of number can be shown either • Overtly, on a noun, a pronoun, a verb, etc., directly referring to how many people or things are involved; or • Covertly, through agreement or other means. Number may be marked: • within an NP • on the head of an NP • by agreement process on a modifier (adjective, article, demonstrative, etc.) • through agreement on verbs, or special suppletive or semi-suppletive verb forms which may code the number of one or more verbal arguments, or additional marker on the verb. -

Andra Kalnača a Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar

Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Copyright © 2014 Andra Kalnača ISBN 978-3-11-041130-0 e- ISBN 978-3-11-041131-7 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Ieva Kalnača Contents Abbreviations I Introduction II 1 The Paradigmatics and Declension of Nouns 1 1.1 Introductory Remarks on Paradigmatics 1 1.2 Declension 4 1.2.1 Noun Forms and Palatalization 9 1.2.2 Nondeclinable Nouns 11 1.3 Case Syncretism 14 1.3.1 Instrumental 18 1.3.2 Vocative 25 1.4 Reflexive Nouns 34 1.5 Case Polyfunctionality and Case Alternation 47 1.6 Gender 66 2 The Paradigmatics and Conjugation of Verbs 74 2.1 Introductory Remarks 74 2.2 Conjugation 75 2.3 Tense 80 2.4 Person 83 3 Aspect 89 -

Declension of Nouns

DECLENSION OF NOUNS In English, the relationship between words in a sentence depends primarily on word order. The difference between the god desires the girl and the girl desires the god is immediately apparent to us. Latin does not depend on word order for basic meaning, but on inflections (changes in the endings of words) to indicate the function of words within a sentence. Thus the god desires the girl can be expressed in Latin deus puellam desiderat, puellam deus desiderat, or desiderat puellam deus without any change in basic meaning. The accusative ending of puellam shows that the girl is being acted upon (i.e., is the object of the verb) and is not the actor (i.e., the subject of the verb). Similarly, the nominative form of deus shows that the god is the actor (agent) in the sentence, not the object of the verb. The inflection of nouns is called declension. The individual declensions are called cases, and together they form the case system. Nouns, pronouns, adjectives and participles are declined in six Cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and vocative and two Numbers (singular and plural). (The locative, an archaic case, existed in the classical period only for a few words). Nominative Indicates the subject of a sentence. (The boy loves the book). Genitive Indicates possession. (The boy loves the girl’s book). Dative Indicates indirect object. (The boy gave the book to the girl). Accusative Indicates direct object. (The boy loves the book). Ablative Answers the questions from where? by what means? how? from what cause? in what manner? when? or where? The ablative is used to show separation (from), instrumentality or means (by, with), accompaniment (with), or locality (at). -

How to Find Serial Verbs in English

How to Find Serial Verbs in English JOHN R. ROBERTS SIL International 1. Introducing Serial Verb Constructions Trask (1993:251-252) describes a serial verb construction (SVC) as: “A construction in which what appears to be a single clause semantically is expressed syntactically by a sequence of juxtaposed separate verbs, all sharing the same subject or agent but each with its own additional arguments, without the use of overt coordinating conjunctions.” Trask gives (1a-b) as examples of typical SVCs from the West African languages of Yoruba and Vagala. (1) a. Yoruba (West African) ó mú ìwé wá 3sg took book came „He brought the book.‟ b. Vagala (West African) ù kpá kíyzèé mòng ówl 3sg take knife cut meat „He cut the meat with a knife.‟ In a more recent cross-linguistic typological study, Aikhenvald (2006) says: “A serial verb construction (SVC) is a sequence of verbs which act together as a single predicate, without any overt marker of coordination, subordination, or syntactic dependency of any sort. Serial verb constructions describe what is conceptualized as a single event. They are monoclausal; their intonational properties are the same as those of a monoverbal clause, and they have just one tense, aspect and polarity value. SVCs may also share core and other arguments. Each component of an SVC must be able to occur on its own. Within an SVC, the individual verbs may have same, or different, transitivity values.” Aikhenvald (2006:1) also says SVCs are widespread in Creole languages, in the languages of West Africa, Southeast Asia (Chinese, Thai, Khmer, etc.), Amazonia, Oceania, and New Guinea.