Negation, Referentiality and Boundedness In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Not So Quirky: on Subject Case in Ice- Landic1

5 Not so Quirky: On Subject Case in Ice- landic 1 JÓHANNES GÍSLI JÓNSSON 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of subject case in Icelandic, extending and refining the observations of Jónsson (1997-1998) and some earlier work on this topic. It will be argued that subject case in Icelandic is more predictable from lexical semantics than previous studies have indicated (see also Mohanan 1994 and Narasimhan 1998 for a similar conclusion about Hindi). This is in line with the work of Jónsson (2000) and Maling (2002) who discuss various semantic generalizations about case as- signment to objects in Icelandic. This paper makes two major claims. First, there are semantic restrictions on non-nominative subjects in Icelandic which go far beyond the well- known observation that such subjects cannot be agents. It will be argued that non-nominative case is unavailable to all kinds of subjects that could be described as agent-like, including subjects of certain psych-verbs and intransitive verbs of motion and change of state. 1 I would like to thank audiences in Marburg, Leeds, York and Reykjavík and three anony- mous reviewers for useful comments. This study was supported by grants from the Icelandic Science Fund (Vísindasjóður) and the University of Iceland Research Fund (Rannsóknasjóður HÍ). New Perspectives in Case Theory. Ellen Brandner and Heike Zinsmeister (eds.). Copyright © 2003, CSLI Publications. 129 130 / JOHANNES GISLI JONSSON Second, the traditional dichotomy between structural and lexical case is insufficient in that two types of lexical case must be recognized: truly idio- syncratic case and what we might call semantic case. -

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

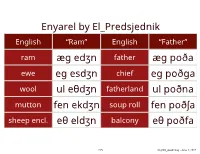

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

The Morphology of Modern Western Abenaki

The Morphology of Modern Western Abenaki Jesse Beach ‘04 Honors Thesis Dartmouth College Program of Linguistics & Cognitive Science Primary Advisor: Prof. David Peterson Secondary Advisor: Prof. Lindsay Whaley May 17, 2004 Acknowledgements This project has commanded a considerable amount of my attention and time over the past year. The research has lead me not only into Algonquian linguistics, but has also introduced me to the world of Native American cultures. The history of the Abenaki people fascinated me as much as their language. I must extnd my fullest appreciate to my advisor David Peterson, who time and again proposed valuable reference suggestions and paths of analysis. The encouragement he offered was indispensable during the research and writing stages of this thesis. He also went meticulously through the initial drafts of this document offering poignant comments on content as well as style. My appreciation also goes to my secondary advisor Lindsay Whaley whose door is always open for a quick chat. His suggestions helped me broaden the focus of my research. Although I was ultimately unable to arrange the field research component of this thesis, the generosity of the Dean of Faculty’s Office and the Richter Memorial Trust Grant that I received from them assisted me in gaining a richer understanding of the current status of the Abenaki language. With the help of this grant, I was able to travel to Odanak, Quebec to meet the remaining speakers of Abenaki. From these conversations I was able to locate additional materials that aided me tremendously in my analysis. Many individuals have offered me assistance in one form or another throughout the unfolding of my research. -

Nominal and Verbal Parameters in the Diachrony of Differential Object Marking in Spanish Marco García García University of Cologne

Chapter 8 Nominal and verbal parameters in the diachrony of differential object marking in Spanish Marco García García University of Cologne This paper deals with the influence that nominal and verbal parameters have on DOMinthe diachrony of Spanish. Comparing selected corpus studies, I will focus first on the different nominal parameters that build up the animacy and referentiality scales, in particular on an- imacy and definiteness. In order to clarify how far DOM has diachronically evolved, special attention will be paid to inanimate objects, which can be viewed as the alleged endpointin the development of DOM in Spanish. Secondly, I will provide a systematic overview of the relevant verbal parameters, which include aspect, affectedness and agentivity. The study will show a complex interaction of nominal and verbal parameters, revealing some unex- pected correlations: Obligatory object marking is not only found with human and strongly affected objects involved in a telic event, but also with inanimate, non-affected andagen- tive objects embedded in a stative event. In other words, in Spanish DOM patterns with both extremely high and extremely low transitivity. These findings sharply contrast with traditional accounts concerning the development as well as the explanation of DOM. 1 Introduction Differential object marking (DOM) is a well-attested phenomenon within Romance lan- guages (for an overview see Bossong 1998: 218–230). While in some Romance languages, such as Catalan or Modern Portuguese, DOM is confined to a reduced number of con- texts, in others, such as Sardinian or Spanish, it is found in many more contexts. This paper will focus on Spanish, where DOM seems to have reached a greater stage of de- velopment than in any other Romance language. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Hundred Sentences and XFST Assignments

Hundred Sentences and XFST Assignments 2-19-14 Your assignment • Make an elicitation checklist of at least 100 sentences covering these things: – Transitive and intransitive verbs. – Semantic verb classes: stativity, dynamicity, and telicity. – Tense/mood/aspect – Special sentence types: • Existential • Copula • Possession • Questions – Speech acts: • Statement • Command/prohibition • Question – Negation Your assignment continued • Noun types – Pronoun – Common – Proper – Count/Mass – Concrete/Abstract • Noun phrases – Definiteness – Possession – Proximity – Diminutive/Augmentative – Quantity • Cardinal numbers • Quantifiers: all, each, both, some – Ordinal (first, second) – Partitive • The top of the tree • The bottom of the tree Your assignment continued • Adjectives – Comparative – Superlative – Intensive (very) – Unintensive (a little) • Adpositions and/or case marking • Typical modiers of nouns and verbs. – Location, time, manner, etc. Example: Belele (Bwele) (Inspiration from Warlpiri and Iñupiaq) Bele-le word-generic Intransitive sentences. SV word order. “Wordkind” Fwe-le bar -la -to Verb morphology: root-aspect-tense Bird-gener sing-hab-pres “Birds sing” Aspects: habitual -la Fwe-n bar -la -to Punctual Ø Bird-def sing-hab-pres Inceptive -go “The bird sings” Fwe-n bar-na Tenses: Bird-def sing-past Present -to “The bird sang” Past -na Fwe-n bar- go- na Bird-def sing-incep-past “The bird started to sing” Example continued • Compound noun: First element not marked for number and definiteness Nar -bi ndo –ki -n There are adjective stems, but they happy -one day –pl –def have to be turned into nouns in order “the happy days” to use them. -bi turns an adjective into a noun. • Two noun phrases (either order, or can be discontinuous): Nar -bi -ki -n ndo –ki -n happy -one –pl-def day –pl –def Nouns and their modifiers can be in either order of can be “the happy ones the days” separated if the modifier is marked for number and ndo –ki -n nar -bi -ki -n definiteness. -

The Syntax of Answers to Negative Yes/No-Questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University

The syntax of answers to negative yes/no-questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University 1. Introduction This paper will argue that answers to polar questions or yes/no-questions (YNQs) in English are elliptical expressions with basically the structure (1), where IP is identical to the LF of the IP of the question, containing a polarity variable with two possible values, affirmative or negative, which is assigned a value by the focused polarity expression. (1) yes/no Foc [IP ...x... ] The crucial data come from answers to negative questions. English turns out to have a fairly complicated system, with variation depending on which negation is used. The meaning of the answer yes in (2) is straightforward, affirming that John is coming. (2) Q(uestion): Isn’t John coming, too? A(nswer): Yes. (‘John is coming.’) In (3) (for speakers who accept this question as well formed), 1 the meaning of yes alone is indeterminate, and it is therefore not a felicitous answer in this context. The longer version is fine, affirming that John is coming. (3) Q: Isn’t John coming, either? A: a. #Yes. b. Yes, he is. In (4), there is variation regarding the interpretation of yes. Depending on the context it can be a confirmation of the negation in the question, meaning ‘John is not coming’. In other contexts it will be an infelicitous answer, as in (3). (4) Q: Is John not coming? A: a. Yes. (‘John is not coming.’) b. #Yes. In all three cases the (bare) answer no is unambiguous, meaning that John is not coming. -

1 Aspect Marking and Modality in Child Vietnamese

1 Aspect Marking and Modality in Child Vietnamese Jennie Tran and Kamil Deen University of Hawai‛i at Mānoa This paper examines the acquisition of aspect morphology in the naturalistic speech of a Vietnamese child, aged 1;9. It shows that while the omission of aspect markers is the predominant error, errors of commission are somewhat more frequent than expected (~20%). Errors of commission are thought to be exceedingly rare in child speech (<4%, Sano & Hyams, 1994), and thus it appears as if these errors in child Vietnamese are more common than in other languages. They occur exclusively with perfective markers in modal contexts, i.e., perfective markers occur with non-perfective, but modal interpretation. We propose, following Hyams (2002), that these errors are permitted by the child’s grammar since perfective features license mood. Additional evidence from the corpus shows that all the perfective-marked verbs in modal context are eventive verbs. We thus further propose that the corollary to RIs in Vietnamese is perfective verbs in modal contexts. 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND There has been considerable debate regarding the acquisition of tense and aspect by young children. Studies on the acquisition of tense-aspect morphology have either attempted to make a general distinction between tense and aspect, or the more specific distinction between grammatical and lexical aspect, or they have centered their analyses around Vendler’s (1967) four-way classification of the inherent semantics of verbs: achievement, accomplishment, activity, and state. The majority of the studies have concluded that the use of tense and aspect inflectional morphology is initially restricted to certain semantic classes of verbs (Bronkard and Sinclair 1973, Antinucci and Miller 1976, Bloom et al.