Minimum of English Grammar Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

Definiteness Determined by Syntax: a Case Study in Tagalog 1 Introduction

Definiteness determined by syntax: A case study in Tagalog1 James N. Collins Abstract Using Tagalog as a case study, this paper provides an analysis of a cross-linguistically well attested phenomenon, namely, cases in which a bare NP’s syntactic position is linked to its interpretation as definite or indefinite. Previous approaches to this phenomenon, including analyses of Tagalog, appeal to specialized interpretational rules, such as Diesing’s Mapping Hypothesis. I argue that the patterns fall out of general compositional principles so long as type-shifting operators are available to the gram- matical system. I begin by weighing in a long-standing issue for the semantic analysis of Tagalog: the interpretational distinction between genitive and nominative transitive patients. I show that bare NP patients are interpreted as definites if marked with nominative case and as narrow scope indefinites if marked with genitive case. Bare NPs are understood as basically predicative; their quantificational force is determined by their syntactic position. If they are syntactically local to the selecting verb, they are existentially quantified by the verb itself. If they occupy a derived position, such as the subject position, they must type-shift in order to avoid a type-mismatch, generating a definite interpretation. Thus the paper develops a theory of how the position of an NP is linked to its interpretation, as well as providing a compositional treatment of NP-interpretation in a language which lacks definite articles but demonstrates other morphosyntactic strategies for signaling (in)definiteness. 1 Introduction Not every language signals definiteness via articles. Several languages (such as Russian, Kazakh, Korean etc.) lack articles altogether. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

Syntax and Morphology Semantics

Parent Tip Sheet Language Syntax & Morphology yntax is the development of sentence structure meaning your child’s first attempts at putting two words together. SMorphology refers to the structure and construction of words and the rules that determine changes in word meaning; it’s knowing plural forms 9 and correct use of verb tense. Introduce words from many different categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. The emergence of first words 9 typically begins around 12 months of Use the Plus One Rule: add a word to expand the length of your child’s utterance to model longer sentences. Also use correct grammar, even age. Syntax typically begins when if it means adding more than one word. E.g., if your child says ‘blue a child begins to combine words in ball” you can say “The blue ball is big.” early two word utterances (ex. Daddy 9 work) around 18-24 months. Read books with repetition, such as: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or I Went Walking. 9 A child needs approximately 50 Watch videos of people or objects in action and describe what is happening. words to begin to combine them 9 Pay attention to the use of plurals with an “s”, add them whenever into short phrases. When children possible. Point out words that do not use an “s” to be plural (e.g., men, begin to learn words, they learn that children) to understand placement in space. some words refer to objects, some 9 Play games with “in” and “on.” To focus on correlation with space. -

Mandative Subjunctive in Arabic Syntax: a Minimalist Study

البلقاء للبحوث Al-Balqa Journal for Research and Studies والدراسات Volume 16 Issue 1 Article 6 2013 Mandative Subjunctive in Arabic Syntax: A Minimalist Study Atef Jalabneh King Khalid University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/albalqa Recommended Citation Jalabneh, Atef (2013) "Mandative Subjunctive in Arabic Syntax: A Minimalist Study," Al-Balqa Journal for .Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 6 :البلقاء للبحوث والدراسات Research and Studies Available at: https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/albalqa/vol16/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Arab Journals Platform. It has been accepted for by an authorized editor. The journal البلقاء للبحوث والدراسات inclusion in Al-Balqa Journal for Research and Studies is hosted on Digital Commons, an Elsevier platform. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Mandative Subjunctive in Arabic Syntax: A Minimalist Study Dr. Atef Jalabneh Faculty of Languages and Translation-King Khalid University Abha- Saudi Arabia Abstract An Arabic sentence is dealt with in this article as SVO at spell-out and VSO at the logical form (LF). Thus, the objective of this study is to check the grammaticality of the mandative subjunctive structure in the absence of a case assignor for the nominative case. It also checks the relevant syntactic and semantic formal and informal features that support the grammaticality of mandative subjunctive at LF. To achieve the objectives, the researcher refers to Chomsky’ s (1981, 1986a, 1986b and 1995) Minimalist Views and Radford’s (1988) Empty Tense Theory. -

Official! Morphology & Syntax Syllabus

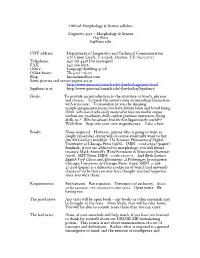

Official Morphology & Syntax syllabus Linguistics 4050 – Morphology & Syntax Haj Ross [email protected] UNT address: Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication 1155 Union Circle, # 305298, Denton, TX 76203-5017 Telephone: 940 565 4458 [for messages] FAX: 940 369 8976 Office: Language Building 407K Office hours: Th 4:00 – 6:00 Blog: haj.nadamelhor.com Some poetics and syntax papers are at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/hajpapers.html Squibnet is at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/haj/Squibnet/ Goals: To provide an introduction to the structure of words, phrases and clauses. To hook the unwary into an unending fascination with structure. To reawaken in you the sleeping morphopragmantactician you have always been and loved being. (Hint: who was it who easily mastered at least one mother tongue without any vocabulary drills, explicit grammar instruction, boring drills, etc.? Who has always been the best linguist in the world??) Well then. Step into your own magnificence. Take a bow. Books: None required. However, anyone who is going to want to deeply remember syntax will of course eventually want to buy Jim McCawley’s indelible The Syntactic Phenomena of English University of Chicago Press (1988). ISBN: 0226556247 (paper). Similarly, if you are addicted to morphology, you will always treasure Mark Aronoff’s Word Formation in Generative Grammar (1976). MIT Press. ISBN: 0-262-51017-0. And Beth Levin’s English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993) ISBN 0-226- 47533-6 (paper) is a delicious cookie jar of weird (and unweird) classes of verbs that you may have thought you had forgotten since you were three. -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Yes, It Is True. While Chinese Sound and Writing Systems Can Be Challenging for Some Learners, Chinese Grammar Is Rarely Deemed Difficult

Grammar I’ve heard that Chinese grammar is relatively easy. Is it true? Yes, it is true. While Chinese sound and writing systems can be challenging for some learners, Chinese grammar is rarely deemed difficult. Chinese is not an inflectional language, meaning it does not distinguish gender, person, tense, case, number, etc. Its sentence structures are mostly straightforward, and many of them overlap with English grammar. For example, the common English structure ‘Subject + Verb + Object’ structure, e.g. I love you, or My dog ate my homework, is also widely used in Chinese. What are some of the unique characteristics of Chinese grammar? Adjectives Are Verbs: Adjectives, or stative verbs, function as verbs, and are usually preceded by an intensifier such as ‘hěn’ (very), or ‘yǒudiǎnr’ (a little). Use of shì,verb ‘to be’,as is required in the English grammar (He is tall), is prohibited. Some examples: Zhōngwén hěn róngyì. (‘Chinese very easy.’) → Chinese is easy. Yīngwén yǒudiǎnr nán. (‘English a little hard.’) → English is a little hard. Note that the intensifier is dropped when a comparison is made: Zhōngwén róngyì. (‘Chinese easy.’) → Chinese is easier. Yīngwén nán. (‘English hard.’) → English is harder. Principle of Temporal sequence: Word order in a Chinese sentence can be very different from that in an English one, where the subject and verb often precede other linguistic units such as prepositions and time word, e.g. ‘I went to New York by train with a friend last weekend.’ A Chinese sentence, on the other hand, follows a temporal sequence principle in which word order is determined based on the relative sequence. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics.