Essentials of Language Typology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

Manual for Language Test Development and Examining

Manual for Language Test Development and Examining For use with the CEFR Produced by ALTE on behalf of the Language Policy Division, Council of Europe © Council of Europe, April 2011 The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All correspondence concerning this publication or the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Director of Education and Languages of the Council of Europe (Language Policy Division) (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). The reproduction of extracts is authorised, except for commercial purposes, on condition that the source is quoted. Manual for Language Test Development and Examining For use with the CEFR Produced by ALTE on behalf of the Language Policy Division, Council of Europe Language Policy Division Council of Europe (Strasbourg) www.coe.int/lang Contents Foreword 5 3.4.2 Piloting, pretesting and trialling 30 Introduction 6 3.4.3 Review of items 31 1 Fundamental considerations 10 3.5 Constructing tests 32 1.1 How to define language proficiency 10 3.6 Key questions 32 1.1.1 Models of language use and competence 10 3.7 Further reading 33 1.1.2 The CEFR model of language use 10 4 Delivering tests 34 1.1.3 Operationalising the model 12 4.1 Aims of delivering tests 34 1.1.4 The Common Reference Levels of the CEFR 12 4.2 The process of delivering tests 34 1.2 Validity 14 4.2.1 Arranging venues 34 1.2.1 What is validity? 14 4.2.2 Registering test takers 35 1.2.2 Validity -

Syntax and Morphology Semantics

Parent Tip Sheet Language Syntax & Morphology yntax is the development of sentence structure meaning your child’s first attempts at putting two words together. SMorphology refers to the structure and construction of words and the rules that determine changes in word meaning; it’s knowing plural forms 9 and correct use of verb tense. Introduce words from many different categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. The emergence of first words 9 typically begins around 12 months of Use the Plus One Rule: add a word to expand the length of your child’s utterance to model longer sentences. Also use correct grammar, even age. Syntax typically begins when if it means adding more than one word. E.g., if your child says ‘blue a child begins to combine words in ball” you can say “The blue ball is big.” early two word utterances (ex. Daddy 9 work) around 18-24 months. Read books with repetition, such as: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or I Went Walking. 9 A child needs approximately 50 Watch videos of people or objects in action and describe what is happening. words to begin to combine them 9 Pay attention to the use of plurals with an “s”, add them whenever into short phrases. When children possible. Point out words that do not use an “s” to be plural (e.g., men, begin to learn words, they learn that children) to understand placement in space. some words refer to objects, some 9 Play games with “in” and “on.” To focus on correlation with space. -

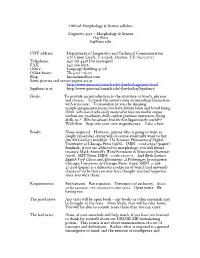

Official! Morphology & Syntax Syllabus

Official Morphology & Syntax syllabus Linguistics 4050 – Morphology & Syntax Haj Ross [email protected] UNT address: Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication 1155 Union Circle, # 305298, Denton, TX 76203-5017 Telephone: 940 565 4458 [for messages] FAX: 940 369 8976 Office: Language Building 407K Office hours: Th 4:00 – 6:00 Blog: haj.nadamelhor.com Some poetics and syntax papers are at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/hajpapers.html Squibnet is at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/haj/Squibnet/ Goals: To provide an introduction to the structure of words, phrases and clauses. To hook the unwary into an unending fascination with structure. To reawaken in you the sleeping morphopragmantactician you have always been and loved being. (Hint: who was it who easily mastered at least one mother tongue without any vocabulary drills, explicit grammar instruction, boring drills, etc.? Who has always been the best linguist in the world??) Well then. Step into your own magnificence. Take a bow. Books: None required. However, anyone who is going to want to deeply remember syntax will of course eventually want to buy Jim McCawley’s indelible The Syntactic Phenomena of English University of Chicago Press (1988). ISBN: 0226556247 (paper). Similarly, if you are addicted to morphology, you will always treasure Mark Aronoff’s Word Formation in Generative Grammar (1976). MIT Press. ISBN: 0-262-51017-0. And Beth Levin’s English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993) ISBN 0-226- 47533-6 (paper) is a delicious cookie jar of weird (and unweird) classes of verbs that you may have thought you had forgotten since you were three. -

Convergence and Divergence in Language Contact Situations

Sonderforschungsbereich Mehrsprachigkeit International Colloquium on Convergence and Divergence in Language Contact Situations 18–20 October 2007 University of Hamburg Research Centre on Multilingualism Welcome On behalf of our Research Centre on Multilingualism (Sonderforschungsbereich Mehrsprachigkeit), generously supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and the University of Hamburg, we would like to welcome you all here in Hamburg. This colloquium deals with issues related to convergence and divergence in language contact situations, issues which had been rather neglected in the past but have received much more attention in recent years. Five speakers from different countries have kindly accepted our invitation to share their expertise with us by presenting their research related to the theme of this colloquium. (One colleague from the US fell seriously ill and deeply regrets not being able to join us. Unfortunately, another invited speak- er cancelled his talk only two weeks ago.) All the other presentations are re- ports from ongoing work in the (now altogether 18) research projects in our centre. We hope that the three conference days will be informative and stimulating for all of us, and that the colloquium will be remembered for both its friendly atmosphere and its lively, controversial discussions. The organising commit- tee has done its best to ensure that this meeting with renowned colleagues from abroad will be a good place to make new friends or reinforce long-stand- ing professional contacts. There will be many opportunities for doing that – during the coffee breaks and especially during the conference dinner at an ex- cellent French restaurant on Thursday evening. -

Language Development Language Development

Language Development rom their very first cries, human beings communicate with the world around them. Infants communicate through sounds (crying and cooing) and through body lan- guage (pointing and other gestures). However, sometime between 8 and 18 months Fof age, a major developmental milestone occurs when infants begin to use words to speak. Words are symbolic representations; that is, when a child says “table,” we understand that the word represents the object. Language can be defined as a system of symbols that is used to communicate. Although language is used to communicate with others, we may also talk to ourselves and use words in our thinking. The words we use can influence the way we think about and understand our experiences. After defining some basic aspects of language that we use throughout the chapter, we describe some of the theories that are used to explain the amazing process by which we Language9 A system of understand and produce language. We then look at the brain’s role in processing and pro- symbols that is used to ducing language. After a description of the stages of language development—from a baby’s communicate with others or first cries through the slang used by teenagers—we look at the topic of bilingualism. We in our thinking. examine how learning to speak more than one language affects a child’s language develop- ment and how our educational system is trying to accommodate the increasing number of bilingual children in the classroom. Finally, we end the chapter with information about disorders that can interfere with children’s language development. -

Chapter One Approaching a Century of Markedness

Chapter One Approaching a Century of Markedness 1.1 Comparative-Historical Origins The concept of markedness originated within the vibrant cultural and intellectual milieu of early twentieth century European structural linguistics, which itself developed largely as an alternative to the comparative-historical linguistics that dominated the nineteenth century. "The history and comparison of languages is the hallmark of nineteenth century linguistics ... [This] approach pervaded the century, and came to be viewed as the only 'scientific' approach to language" (Morpurgo-Davies 1992, 159). Comparisons between genetically related lan guages-chiefly at the levels of phonology and morphology-dominated the work of many scholars during this age, helping to establish several theoretical and methodological foundations for modem and contemporary linguistics. An important catalyst for comparative-historical linguistics was achieved through the late eighteenth century discovery of formal similarities between Sanskrit and numerous other languages, including Greek, Latin, Russian, German, and English. This recognition led to the delineation of the Indo European (IE) family of languages. 1 The German scholar Franz Bopp is gener ally credited with foundi~g modem comparative-historical linguistics by virtue of his 1816 publication, Uber das Konjugationssystem der Sanskritsprache: in Vergleichung mit jenem der griechischen, lateinischen, persischen und german ischen Sprache. As the title indicates, Bopp examined and compared the verbal systems among several IE languages in an effort to demonstrate a common genetic link between them. The novelty of Bopp's approach lay in his attention to isolating certain formal (i.e., phonological and morphological) regularities among the data he compared. Bopp realized that such regularities-or, laws could be extrapolated to reconstruct unattested linguistic forms (see Jankowsky 1972, 57-59). -

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: a Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, Thierry Poibeau, Ekaterina Shutova, Anna Korhonen To cite this version: Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, et al.. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing. 2018. hal-01856176 HAL Id: hal-01856176 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01856176 Preprint submitted on 9 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Maria Ponti∗ Helen O’Horan∗∗ LTL, University of Cambridge LTL, University of Cambridge Yevgeni Berzaky Ivan Vuli´cz Department of Brain and Cognitive LTL, University of Cambridge Sciences, MIT Roi Reichart§ Thierry Poibeau# Faculty of Industrial Engineering and LATTICE Lab, CNRS and ENS/PSL and Management, Technion - IIT Univ. Sorbonne nouvelle/USPC Ekaterina Shutova** Anna Korhonenyy ILLC, University of Amsterdam LTL, University of Cambridge Understanding cross-lingual variation is essential for the development of effective multilingual natural language processing (NLP) applications. -

“The New Look” in the History of Linguistics (1965)

“The New Look” in the History of Linguistics (1965) W. Keith Percival What follows here is a summary of a paper presented at the 128th Meeting of the Lin- guistic Circle of Madison on December 9, 1965. A complete typescript or manuscript has not survived. Fortunately, Jon Erickson, the recorder of the Linguistic Circle of Madison, entered this detailed digest of the paper into the Linguistic Circle’s minutes. At the request of Charles T. Scott, the secretary of the Madison Linguistics department graciously provided me with copies of the minutes referring to all the papers that I presented to the Linguistic Circle in the years 1965- 69 while I was teaching linguistics at the Milwaukee campus of the University of Wisconsin. Needless to say, I feel much indebted to Professors Scott and Erickson, and to the departmental secretary. ---------- The purpose of “‘The New Look’ in the History of Linguistics” was to review two stan- dard treatises on the history of linguistics, namely Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft in Deutschland by Theodor Benfey (1869), and Linguistic Science in the Nineteenth Century by Holger Pedersen (1931) . In spite of the way Theodor Benfey (1809–1881) implicitly outlined the subject matter of his book in the title [“History of Linguistics and Oriental Philology since the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, with a Retrospective Glance at Earlier Periods”], he in fact devoted much attention to linguistic studies spanning the entire period from the end of the medieval period to the beginning of the nineteenth century. In his so-called retrospective survey [Rückblick auf die früheren Zeiten ], he dealt with the Renaissance and the eighteenth century in remarkable detail. -

Franz Bopp an August Wilhelm Von Schlegel Berlin, 16.06.1824

Franz Bopp an August Wilhelm von Schlegel Berlin, 16.06.1824 Empfangsort Bonn Anmerkung Unvollständiger Druck. Empfangsort erschlossen. Handschriften-Datengeber Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek - Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Signatur Mscr.Dresd.e.90,XIX,Bd.3,Nr.72 Blatt-/Seitenzahl 4 S. auf Doppelbl., hs. m. U. Format 24 x 19,5 cm Lefmann, S.: Franz Bopp, sein Leben und seine Wissenschaft. Erste Hälfte. Berlin 1891, S. Bibliographische Angabe 94‒95. Editionsstatus Einmal kollationierter Druckvolltext mit Registerauszeichnung August Wilhelm Schlegel: Digitale Edition der Korrespondenz [Version-07-21];https://august- Zitierempfehlung wilhelm-schlegel.de/version-07-21/letters/view/1596. [4] Berlin, den 16. Juni 1824. [1] Hochwohlgeborener, Hochgeehrtester Herr Professor! Vor allem erstatte ich Ew. Hochwohlgeboren meinen verbindlichsten Dank für die schätzbaren Geschenke, welche Sie mir durch Ihre vortreffliche Ausgabe des Bhag. und das 4te Heft der Ind. Bibl. gemacht. Wie sehr ich die erstere achte habe ich bereits Gelegenheit gehabtöffentlich auszusprechen ; zur Anzeige des 4ten Heftes wollte ich die Erscheinung des 1ten Hefts 2ten Bandes, wegen des Schlusses der Humboldtschen Abhandlung abwarten. Ihre kurzen aber lichtvoIlen Anmerkungen zu dessen Abhandlung haben mich sehr erfreut, sowie die schätzbaren Varianten ausPariser der Handschrift. [2] . Sie erhalten hierbei ein Exemplareiner kleinen Sammlung von Episoden ausdem Mah., um dessen wohlwollende Annahme ich Sie ergebenst bitte und hoffe, daß Ihnen das Durchlesen des Originals einige vergnügte Stunden machen werde. Es sind viele schwierige und dunkle Stellen darin, die ich in den Anmerkungen so viel es mir möglich gewesen zu erläutern gesucht habe. Ihre belehrenden Ansichten darüber werde ich mit vielem Danke aufnehmen. In der Schreibung des Textes werden Sie finden, daß ich in manchen Punkten Ihrem im Bhag. -

Basic Morphology

What is Morphology? Mark Aronoff and Kirsten Fudeman MORPHOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 1 Thinking about Morphology and Morphological Analysis 1.1 What is Morphology? 1 1.2 Morphemes 2 1.3 Morphology in Action 4 1.3.1 Novel words and word play 4 1.3.2 Abstract morphological facts 6 1.4 Background and Beliefs 9 1.5 Introduction to Morphological Analysis 12 1.5.1 Two basic approaches: analysis and synthesis 12 1.5.2 Analytic principles 14 1.5.3 Sample problems with solutions 17 1.6 Summary 21 Introduction to Kujamaat Jóola 22 mor·phol·o·gy: a study of the structure or form of something Merriam-Webster Unabridged n 1.1 What is Morphology? The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright, and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who coined it early in the nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is Greek: morph- means ‘shape, form’, and morphology is the study of form or forms. In biology morphology refers to the study of the form and structure of organisms, and in geology it refers to the study of the configuration and evolution of land forms. In linguistics morphology refers to the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch 2 MORPHOLOGYMORPHOLOGY ANDAND MORPHOLOGICAL MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS ANALYSIS of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure, and how they are formed. n 1.2 Morphemes A major way in which morphologists investigate words, their internal structure, and how they are formed is through the identification and study of morphemes, often defined as the smallest linguistic pieces with a gram- matical function. -

Dative Overmarking in Basque: Evidence of Spanish-Basque Convergence

Dative Overmarking in Basque: Evidence of Spanish-Basque Convergence Jennifer Austin University of New Jersey, Rutgers. [email protected] Abstract This paper investigates a recent change in the grammar of spoken Basque which results in the substitution of dative case and agreement for absolutive case and agreement in marking animate, specific direct objects. I argue that this pattern of use is due to convergence between the feature matrix of the functional category AGR in Spanish and Basque. In contrast to previous studies which point to interface areas as the locus of syntactic convergence, I argue that this is a change affecting the core grammar of Basque. Furthermore, I suggest that the appearance of this case marking pattern in spoken Basque is probably attributable to recent changes in the demographics of Basque speakers and that its use is related to the degree of proficiency in each language of adult bilingual speakers. Laburpena Lan honetan euskara mintzatuaren gramatikan gertatu berri den aldaketa bat ikertzen da, hain zuzen ere, kasu datiboa eta aditz komunztaduraren ordezkapena kasu absolutiboa eta aditz komunztaduraren ordez objektu zuzenak --animatuak eta zehatzak—markatzen direnean. Nire iritziz, erabilera hori gazteleraz eta euskaraz dagoen AGR delako kategori funtzionalaren ezaugarri taulen bateratzeari zor zaio. Aurreko ikerketa batzuetan hizkuntza arteko ukipen eremuak bateratze sintaktikoaren gunetzat jotzen badira ere, nire iritziz aldaketa horrek euskararen gramatika oinarrizkoari eragiten dio. Areago, esango nuke kasu marka erabilera hori, ziurrenik, euskal hiztunen artean gertatu berri diren aldaketa demografikoen ondorioz agertzen dela euskara mintzatuan eta hiztun elebidun helduek hizkuntza bakoitzean daukaten gaitasun mailari lotuta dagoela. Keywods: Bilingualism, syntactic convergence, language contact.