Implementing the Morphology-Syntax Interface: Challenges from Murrinh-Patha Verbs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

Syntax and Morphology Semantics

Parent Tip Sheet Language Syntax & Morphology yntax is the development of sentence structure meaning your child’s first attempts at putting two words together. SMorphology refers to the structure and construction of words and the rules that determine changes in word meaning; it’s knowing plural forms 9 and correct use of verb tense. Introduce words from many different categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. The emergence of first words 9 typically begins around 12 months of Use the Plus One Rule: add a word to expand the length of your child’s utterance to model longer sentences. Also use correct grammar, even age. Syntax typically begins when if it means adding more than one word. E.g., if your child says ‘blue a child begins to combine words in ball” you can say “The blue ball is big.” early two word utterances (ex. Daddy 9 work) around 18-24 months. Read books with repetition, such as: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or I Went Walking. 9 A child needs approximately 50 Watch videos of people or objects in action and describe what is happening. words to begin to combine them 9 Pay attention to the use of plurals with an “s”, add them whenever into short phrases. When children possible. Point out words that do not use an “s” to be plural (e.g., men, begin to learn words, they learn that children) to understand placement in space. some words refer to objects, some 9 Play games with “in” and “on.” To focus on correlation with space. -

Official! Morphology & Syntax Syllabus

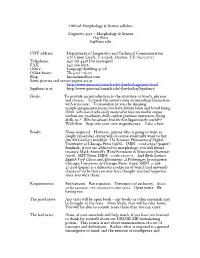

Official Morphology & Syntax syllabus Linguistics 4050 – Morphology & Syntax Haj Ross [email protected] UNT address: Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication 1155 Union Circle, # 305298, Denton, TX 76203-5017 Telephone: 940 565 4458 [for messages] FAX: 940 369 8976 Office: Language Building 407K Office hours: Th 4:00 – 6:00 Blog: haj.nadamelhor.com Some poetics and syntax papers are at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/hajpapers.html Squibnet is at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/haj/Squibnet/ Goals: To provide an introduction to the structure of words, phrases and clauses. To hook the unwary into an unending fascination with structure. To reawaken in you the sleeping morphopragmantactician you have always been and loved being. (Hint: who was it who easily mastered at least one mother tongue without any vocabulary drills, explicit grammar instruction, boring drills, etc.? Who has always been the best linguist in the world??) Well then. Step into your own magnificence. Take a bow. Books: None required. However, anyone who is going to want to deeply remember syntax will of course eventually want to buy Jim McCawley’s indelible The Syntactic Phenomena of English University of Chicago Press (1988). ISBN: 0226556247 (paper). Similarly, if you are addicted to morphology, you will always treasure Mark Aronoff’s Word Formation in Generative Grammar (1976). MIT Press. ISBN: 0-262-51017-0. And Beth Levin’s English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993) ISBN 0-226- 47533-6 (paper) is a delicious cookie jar of weird (and unweird) classes of verbs that you may have thought you had forgotten since you were three. -

Basic Morphology

What is Morphology? Mark Aronoff and Kirsten Fudeman MORPHOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 1 Thinking about Morphology and Morphological Analysis 1.1 What is Morphology? 1 1.2 Morphemes 2 1.3 Morphology in Action 4 1.3.1 Novel words and word play 4 1.3.2 Abstract morphological facts 6 1.4 Background and Beliefs 9 1.5 Introduction to Morphological Analysis 12 1.5.1 Two basic approaches: analysis and synthesis 12 1.5.2 Analytic principles 14 1.5.3 Sample problems with solutions 17 1.6 Summary 21 Introduction to Kujamaat Jóola 22 mor·phol·o·gy: a study of the structure or form of something Merriam-Webster Unabridged n 1.1 What is Morphology? The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright, and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who coined it early in the nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is Greek: morph- means ‘shape, form’, and morphology is the study of form or forms. In biology morphology refers to the study of the form and structure of organisms, and in geology it refers to the study of the configuration and evolution of land forms. In linguistics morphology refers to the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch 2 MORPHOLOGYMORPHOLOGY ANDAND MORPHOLOGICAL MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS ANALYSIS of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure, and how they are formed. n 1.2 Morphemes A major way in which morphologists investigate words, their internal structure, and how they are formed is through the identification and study of morphemes, often defined as the smallest linguistic pieces with a gram- matical function. -

Essentials of Language Typology

Lívia Körtvélyessy Essentials of Language Typology KOŠICE 2017 © Lívia Körtvélyessy, Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky, Filozofická fakulta UPJŠ v Košiciach Recenzenti: Doc. PhDr. Edita Kominarecová, PhD. Doc. Slávka Tomaščíková, PhD. Elektronický vysokoškolský učebný text pre Filozofickú fakultu UPJŠ v Košiciach. Všetky práva vyhradené. Toto dielo ani jeho žiadnu časť nemožno reprodukovať,ukladať do informačných systémov alebo inak rozširovať bez súhlasu majiteľov práv. Za odbornú a jazykovú stánku tejto publikácie zodpovedá autor. Rukopis prešiel redakčnou a jazykovou úpravou. Jazyková úprava: Steve Pepper Vydavateľ: Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach Umiestnenie: http://unibook.upjs.sk Dostupné od: február 2017 ISBN: 978-80-8152-480-6 Table of Contents Table of Contents i List of Figures iv List of Tables v List of Abbreviations vi Preface vii CHAPTER 1 What is language typology? 1 Tasks 10 Summary 13 CHAPTER 2 The forerunners of language typology 14 Rasmus Rask (1787 - 1832) 14 Franz Bopp (1791 – 1867) 15 Jacob Grimm (1785 - 1863) 15 A.W. Schlegel (1767 - 1845) and F. W. Schlegel (1772 - 1829) 17 Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767 – 1835) 17 August Schleicher 18 Neogrammarians (Junggrammatiker) 19 The name for a new linguistic field 20 Tasks 21 Summary 22 CHAPTER 3 Genealogical classification of languages 23 Tasks 28 Summary 32 CHAPTER 4 Phonological typology 33 Consonants and vowels 34 Syllables 36 Prosodic features 36 Tasks 38 Summary 40 CHAPTER 5 Morphological typology 41 Morphological classification of languages (holistic -

Verbal Morphology of the Southern Unami Dialect of Lenape1

Verbal Morphology of the Southern Unami Dialect of Lenape1 Louise St. Amour Abstract Because of a complex system of participant-verb agreement, the Lenape verb has a fascinating role in the structure of a sentence. Not only does the verb contain enough information about the nominal elements in the sentence to make a separate pronoun for the subject and object unnecessary, but it identifies what grammatical role each nominal element will play. It goes about this in a somewhat round-about way, assigning each participant to a morphological category, which itself does not indicate the grammatical role, but is assigned the grammatical role by a separate morpheme called a theme sign. In this thesis, I undertake to make the fascinating basics of Lenape verbal morphology, primarily as described by Goddard in his dissertation Delaware Verbal Morphology: A Descriptive and Comparative Study, more readily accessible. 1 Thanks to Jen Johnson and Charlie Huntington for their helpful feedback on this work. Thanks also to my advisor Nathan Sanders, my Lenape teacher Shelley DePaul, and Ted Fernald. All errors are my own. 1 Table of Contents 1. Intro……………………………………………………………………..…………3 1.1 Purpose 3 1.2 Who are the Lenape? 3 1.3 Sources 4 1.4 Notes on examples, and morphophonology 5 1.5 Structure of this paper 5 2. Noun verb interaction……………………………………………………..……….6 2.1 Nominal properties marked on verbs 6 2.1.1 Gender 6 2.1.2 Number and person 7 2.1.3 Obviation 9 2.1.4 Presence 11 2.1.5 Diminutive and Pejorative 12 2.2 Participants 14 2.2.1 Types of verbs 14 2.2.2 Basic participants for different types of verbs 15 2.2.3 Other patterns of participants 18 3. -

The Importance of Morphology, Etymology, and Phonology

3/16/19 OUTLINE Introduction •Goals Scientific Word Investigations: •Spelling exercise •Clarify some definitions The importance of •Intro to/review of the brain and learning Morphology, Etymology, and •What is Dyslexia? •Reading Development and Literacy Instruction Phonology •Important facts about spelling Jennifer Petrich, PhD GOALS OUTLINE Answer the following: •Language History and Evolution • What is OG? What is SWI? • What is the difference between phonics and •Scientific Investigation of the writing phonology? system • What does linguistics tell us about written • Important terms language? • What is reading and how are we teaching it? • What SWI is and is not • Why should we use the scientific method to • Scientific inquiry and its tools investigate written language? • Goal is understanding the writing system Defining Our Terms Defining Our Terms •Linguistics à lingu + ist + ic + s •Phonics à phone/ + ic + s • the study of languages • literacy instruction based on small part of speech research and psychological research •Phonology à phone/ + o + log(e) + y (phoneme) • the study of the psychology of spoken language •Phonemic Awareness • awareness of phonemes?? •Phonetics à phone/ + et(e) + ic + s (phone) • the study of the physiology of spoken language •Orthography à orth + o + graph + y • correct spelling •Morphology à morph + o + log(e) + y (morpheme) • the study of the form/structure of words •Orthographic phonology • The study of the connection between graphemes and phonemes 1 3/16/19 Defining Our Terms The Beautiful Brain •Phonemeà -

Minimum of English Grammar Glossary

Glossary, Further Definitions and Abbreviations Accusative (See Case) Adjective/Phrase A word/category which often denotes states or well being (e.g., happy, sad), and which can often take an adverb suffix {-ly}(e.g., sad>sadly) or prefix {un-} (e.g., unhappy). Adjectives merge with and modify nouns to form adjective phrases (AdjP) (e.g, red shoes, sad boy, little news). Adverb/Phrase A word/category which often denotes manner (e.g., greatly, quickly, softly). Adverbs merge with and modify verbs to form adverb phrases (e.g., softly spoke, quickly ran). In English, most Adverbs end with the suffix {-ly}. Affix A grammatical morpheme which inflects onto a stem and cannot stand alone as an individual word. A Bound morpheme is a morpheme that must attach to a word stem. A Free morpheme, on the other hand, may stand alone as a free word (e.g., the word visit in re-visit is a free morpheme (and hence a word). The {re-} portion of the word is a prefix and thus bound. A prefix attaches at the beginning of the word, an infix to the middle, and a suffix attaches at the end. Agreement When the Person/Number features of a verb match that of its subject: a Verb-to-Subject relationship of grammatical features. For example, the verb like-s projects {s} due to its 3rd person/singular features matched to the subject John (e.g., John likes syntax). Anaphor An anaphor is an expression (e.g., himself) which cannot have independent reference, but which must take its reference from an antecedent (e.g., He hurt himself)— where himself refers back to He. -

4. the History of Linguistics : the Handbook of Linguistics : Blackwell Reference On

4. The History of Linguistics : The Handbook of Linguistics : Blackwell Reference On... Sayfa 1 / 17 4. The History of Linguistics LYLE CAMPBELL Subject History, Linguistics DOI: 10.1111/b.9781405102520.2002.00006.x 1 Introduction Many “histories” of linguistics have been written over the last two hundred years, and since the 1970s linguistic historiography has become a specialized subfield, with conferences, professional organizations, and journals of its own. Works on the history of linguistics often had such goals as defending a particular school of thought, promoting nationalism in various countries, or focussing on a particular topic or subfield, for example on the history of phonetics. Histories of linguistics often copied from one another, uncritically repeating popular but inaccurate interpretations; they also tended to see the history of linguistics as continuous and cumulative, though more recently some scholars have stressed the discontinuities. Also, the history of linguistics has had to deal with the vastness of the subject matter. Early developments in linguistics were considered part of philosophy, rhetoric, logic, psychology, biology, pedagogy, poetics, and religion, making it difficult to separate the history of linguistics from intellectual history in general, and, as a consequence, work in the history of linguistics has contributed also to the general history of ideas. Still, scholars have often interpreted the past based on modern linguistic thought, distorting how matters were seen in their own time. It is not possible to understand developments in linguistics without taking into account their historical and cultural contexts. In this chapter I attempt to present an overview of the major developments in the history of linguistics, avoiding these difficulties as far as possible. -

A Short History of Morphological Theory∗

A short History of Morphological Theory∗ Stephen R. Anderson Dept. of Linguistics, Yale University Interest in the nature of language has included attention to the nature and structure of words — what we call Morphology — at least since the studies of the ancient Indian, Greek and Arab grammarians, and so any history of the subject that attempted to cover its entire scope could hardly be a short one. Nonetheless, any history has to start somewhere, and in tracing the views most relevant to the state of morphological theory today, we can usefully start with the views of Saussure. No, not that Saussure, not the generally acknowledged progenitor of modern linguis- tics, Ferdinand de Saussure. Instead, his brother René, a mathematician, who was a major figure in the early twentieth century Esperanto movement (Joseph 2012). Most of his written work was on topics in mathematics and physics, and on Esperanto, but de Saussure (1911) is a short (122 page) book devoted to word structure,1 in which he lays out a view of morphology that anticipates one side of a major theoretical opposition that we will follow below. René de Saussure begins by distinguishing simple words, on the one hand, and com- pounds (e.g., French porte-plume ‘pen-holder’) and derived words (e.g., French violoniste ‘violinist’), on the other. For the purposes of analysis, there are only two sorts of words: root words (e.g. French homme ‘man’) and affixes (e.g., French -iste in violoniste). But “[a]u point de vue logique, il n’y a pas de difference entre un radical et un affixe [. -

The Neat Summary of Linguistics

The Neat Summary of Linguistics Table of Contents Page I Language in perspective 3 1 Introduction 3 2 On the origins of language 4 3 Characterising language 4 4 Structural notions in linguistics 4 4.1 Talking about language and linguistic data 6 5 The grammatical core 6 6 Linguistic levels 6 7 Areas of linguistics 7 II The levels of linguistics 8 1 Phonetics and phonology 8 1.1 Syllable structure 10 1.2 American phonetic transcription 10 1.3 Alphabets and sound systems 12 2 Morphology 13 3 Lexicology 13 4 Syntax 14 4.1 Phrase structure grammar 15 4.2 Deep and surface structure 15 4.3 Transformations 16 4.4 The standard theory 16 5 Semantics 17 6 Pragmatics 18 III Areas and applications 20 1 Sociolinguistics 20 2 Variety studies 20 3 Corpus linguistics 21 4 Language and gender 21 Raymond Hickey The Neat Summary of Linguistics Page 2 of 40 5 Language acquisition 22 6 Language and the brain 23 7 Contrastive linguistics 23 8 Anthropological linguistics 24 IV Language change 25 1 Linguistic schools and language change 26 2 Language contact and language change 26 3 Language typology 27 V Linguistic theory 28 VI Review of linguistics 28 1 Basic distinctions and definitions 28 2 Linguistic levels 29 3 Areas of linguistics 31 VII A brief chronology of English 33 1 External history 33 1.1 The Germanic languages 33 1.2 The settlement of Britain 34 1.3 Chronological summary 36 2 Internal history 37 2.1 Periods in the development of English 37 2.2 Old English 37 2.3 Middle English 38 2.4 Early Modern English 40 Raymond Hickey The Neat Summary of Linguistics Page 3 of 40 I Language in perspective 1 Introduction The goal of linguistics is to provide valid analyses of language structure. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chapter 1 Introduction This book presents an account of the syntax of Meskwaki (or Fox), an Algonquian language spoken in Iowa. It also, by necessity, covers the morphology of Meskwaki, because it is impossible to discuss the syntax of an Algonquian language in isolation from morphology. Syntax plays a role in all areas of Meskwaki morphology: for example, the inflectional morphology on verbs is the means by which subjects are distinguished from objects; additional syntactic information is conveyed by the choice of a particular inflectional paradigm. Derivational affixes attached to verb stems may alter the argument structure of the verb, resulting in causative, applicative, antipassive, or other types of verbs. Certain classes of arguments may be incorporated into the verb stem. Even bi- clausal constructions comparable to English raising to object and tough movement affect the morphology of the matrix verb stem. In describing the syntax of Meskwaki it is also necessary to take account of discourse functions, such as topic and focus. For example, word order is mostly influenced by discourse conditions, resulting in a great deal of word order variation, including frequent use of discontinuous constituents. Another place in which syntax and discourse are intertwined is in the discourse-based distinction within third person known as OBVIATION, which plays a key syntactic role in distinguishing subject from object in the agreement system. The theoretical framework assumed here is Lexical Functional Grammar (Bresnan 1982b, 2000), which takes grammatical relations such as subject and object as theoretical primitives. The grammatical relations needed for an analysis of Meskwaki are described in 1.2; 1.3.