Basic Morphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Words: Is Lexicography for You? Lexicographers Decide Which Words Should Be Included in Dictionaries. They May Decide T

Creating Words: Is Lexicography for You? Lexicographers decide which words should be included in dictionaries. They may decide that a word is currently just a fad, and so they’ll wait to see whether it will become a permanent addition to the language. In the past several decades, words such as hippie and yuppie have survived being fads and are now found in regular, not just slang, dictionaries. Other words, such as medicare, were created to fill needs. And yet other words have come from trademark names, for example, escalator. Here are some writing options: 1. While you probably had to memorize vocabulary words throughout your school years, you undoubtedly also learned many other words and ways of speaking and writing without even noticing it. What factors are bringing about changes in the language you now speak and write? Classes? Songs? Friends? Have you ever influenced the language that someone else speaks? 2. How often do you use a dictionary or thesaurus? What helps you learn a new word and remember its meaning? 3. Practice being a lexicographer: Define a word that you know isn’t in the dictionary, or create a word or set of words that you think is needed. When is it appropriate to use this term? Please give some sample dialogue or describe a specific situation in which you would use the term. For inspiration, you can read the short article in the Writing Center by James Chiles about the term he has created "messismo"–a word for "true bachelor housekeeping." 4. Or take a general word such as "good" or "friend" and identify what it means in different contexts or the different categories contained within the word. -

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

Syntax and Morphology Semantics

Parent Tip Sheet Language Syntax & Morphology yntax is the development of sentence structure meaning your child’s first attempts at putting two words together. SMorphology refers to the structure and construction of words and the rules that determine changes in word meaning; it’s knowing plural forms 9 and correct use of verb tense. Introduce words from many different categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. The emergence of first words 9 typically begins around 12 months of Use the Plus One Rule: add a word to expand the length of your child’s utterance to model longer sentences. Also use correct grammar, even age. Syntax typically begins when if it means adding more than one word. E.g., if your child says ‘blue a child begins to combine words in ball” you can say “The blue ball is big.” early two word utterances (ex. Daddy 9 work) around 18-24 months. Read books with repetition, such as: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or I Went Walking. 9 A child needs approximately 50 Watch videos of people or objects in action and describe what is happening. words to begin to combine them 9 Pay attention to the use of plurals with an “s”, add them whenever into short phrases. When children possible. Point out words that do not use an “s” to be plural (e.g., men, begin to learn words, they learn that children) to understand placement in space. some words refer to objects, some 9 Play games with “in” and “on.” To focus on correlation with space. -

Official! Morphology & Syntax Syllabus

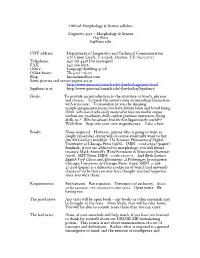

Official Morphology & Syntax syllabus Linguistics 4050 – Morphology & Syntax Haj Ross [email protected] UNT address: Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication 1155 Union Circle, # 305298, Denton, TX 76203-5017 Telephone: 940 565 4458 [for messages] FAX: 940 369 8976 Office: Language Building 407K Office hours: Th 4:00 – 6:00 Blog: haj.nadamelhor.com Some poetics and syntax papers are at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/hajpapers.html Squibnet is at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/haj/Squibnet/ Goals: To provide an introduction to the structure of words, phrases and clauses. To hook the unwary into an unending fascination with structure. To reawaken in you the sleeping morphopragmantactician you have always been and loved being. (Hint: who was it who easily mastered at least one mother tongue without any vocabulary drills, explicit grammar instruction, boring drills, etc.? Who has always been the best linguist in the world??) Well then. Step into your own magnificence. Take a bow. Books: None required. However, anyone who is going to want to deeply remember syntax will of course eventually want to buy Jim McCawley’s indelible The Syntactic Phenomena of English University of Chicago Press (1988). ISBN: 0226556247 (paper). Similarly, if you are addicted to morphology, you will always treasure Mark Aronoff’s Word Formation in Generative Grammar (1976). MIT Press. ISBN: 0-262-51017-0. And Beth Levin’s English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993) ISBN 0-226- 47533-6 (paper) is a delicious cookie jar of weird (and unweird) classes of verbs that you may have thought you had forgotten since you were three. -

Character-Word LSTM Language Models

Character-Word LSTM Language Models Lyan Verwimp Joris Pelemans Hugo Van hamme Patrick Wambacq ESAT – PSI, KU Leuven Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, 3001 Heverlee, Belgium [email protected] Abstract A first drawback is the fact that the parameters for infrequent words are typically less accurate because We present a Character-Word Long Short- the network requires a lot of training examples to Term Memory Language Model which optimize the parameters. The second and most both reduces the perplexity with respect important drawback addressed is the fact that the to a baseline word-level language model model does not make use of the internal structure and reduces the number of parameters of the words, given that they are encoded as one-hot of the model. Character information can vectors. For example, ‘felicity’ (great happiness) is reveal structural (dis)similarities between a relatively infrequent word (its frequency is much words and can even be used when a word lower compared to the frequency of ‘happiness’ is out-of-vocabulary, thus improving the according to Google Ngram Viewer (Michel et al., modeling of infrequent and unknown words. 2011)) and will probably be an out-of-vocabulary By concatenating word and character (OOV) word in many applications, but since there embeddings, we achieve up to 2.77% are many nouns also ending on ‘ity’ (ability, com- relative improvement on English compared plexity, creativity . ), knowledge of the surface to a baseline model with a similar amount of form of the word will help in determining that ‘felic- parameters and 4.57% on Dutch. Moreover, ity’ is a noun. -

Implementing the Morphology-Syntax Interface: Challenges from Murrinh-Patha Verbs

IMPLEMENTING THE MORPHOLOGY-SYNTAX INTERFACE: CHALLENGES FROM MURRINH-PATHA VERBS Melanie Seiss Universitat¨ Konstanz Proceedings of the LFG11 Conference Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2011 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract Polysynthetic languages pose special challenges for the morphology- syntax interface because information otherwise associated with words, phrases and clauses is encoded in a single morphological word. In this pa- per, I am concerned with the implementation of the verbal structure of the polysynthetic language Murrinh-Patha and the questions this raises for the morphology-syntax interface. 1 Introduction The interface between morphology and syntax has been a matter of great de- bate, both for theoretical linguistics and for grammar implementation (see, e.g. the discussions in Sadler and Spencer 2004). Polysynthetic languages pose special challenges for this interface because information otherwise associated with words, phrases and clauses is encoded in a single morphological word. In this paper, I am concerned with the implementation of the verbal structure of the polysynthetic language Murrinh-Patha and the questions this raises for the morphology-syntax interface. The Murrinh-Patha grammar is implemented with the grammar development platform XLE (Crouch et al. 2011) and uses an XFST finite state morphology (Beesley and Karttunen 2003). As Frank and Zaenen (2004) point out, a morphol- ogy module like this in combination with sublexical rules makes a lexicon with fully inflected forms unnecessary, which is especially important for a polysyn- thetic language as listing all possible morphological words would be unfeasible, if not impossible. However, this raises the question of the division of work be- tween syntactic grammar rules in XLE and morphological formations in XFST. -

Learning About Phonology and Orthography

EFFECTIVE LITERACY PRACTICES MODULE REFERENCE GUIDE Learning About Phonology and Orthography Module Focus Learning about the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language (often referred to as letter-sound associations, graphophonics, sound- symbol relationships) Definitions phonology: study of speech sounds in a language orthography: study of the system of written language (spelling) continuous text: a complete text or substantive part of a complete text What Children Children need to learn to work out how their spoken language relates to messages in print. Have to Learn They need to learn (Clay, 2002, 2006, p. 112) • to hear sounds buried in words • to visually discriminate the symbols we use in print • to link single symbols and clusters of symbols with the sounds they represent • that there are many exceptions and alternatives in our English system of putting sounds into print Children also begin to work on relationships among things they already know, often long before the teacher attends to those relationships. For example, children discover that • it is more efficient to work with larger chunks • sometimes it is more efficient to work with relationships (like some word or word part I know) • often it is more efficient to use a vague sense of a rule How Children Writing Learn About • Building a known writing vocabulary Phonology and • Analyzing words by hearing and recording sounds in words Orthography • Using known words and word parts to solve new unknown words • Noticing and learning about exceptions in English orthography Reading • Building a known reading vocabulary • Using known words and word parts to get to unknown words • Taking words apart while reading Manipulating Words and Word Parts • Using magnetic letters to manipulate and explore words and word parts Key Points Through reading and writing continuous text, children learn about sound-symbol relation- for Teachers ships, they take on known reading and writing vocabularies, and they can use what they know about words to generate new learning. -

Essentials of Language Typology

Lívia Körtvélyessy Essentials of Language Typology KOŠICE 2017 © Lívia Körtvélyessy, Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky, Filozofická fakulta UPJŠ v Košiciach Recenzenti: Doc. PhDr. Edita Kominarecová, PhD. Doc. Slávka Tomaščíková, PhD. Elektronický vysokoškolský učebný text pre Filozofickú fakultu UPJŠ v Košiciach. Všetky práva vyhradené. Toto dielo ani jeho žiadnu časť nemožno reprodukovať,ukladať do informačných systémov alebo inak rozširovať bez súhlasu majiteľov práv. Za odbornú a jazykovú stánku tejto publikácie zodpovedá autor. Rukopis prešiel redakčnou a jazykovou úpravou. Jazyková úprava: Steve Pepper Vydavateľ: Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach Umiestnenie: http://unibook.upjs.sk Dostupné od: február 2017 ISBN: 978-80-8152-480-6 Table of Contents Table of Contents i List of Figures iv List of Tables v List of Abbreviations vi Preface vii CHAPTER 1 What is language typology? 1 Tasks 10 Summary 13 CHAPTER 2 The forerunners of language typology 14 Rasmus Rask (1787 - 1832) 14 Franz Bopp (1791 – 1867) 15 Jacob Grimm (1785 - 1863) 15 A.W. Schlegel (1767 - 1845) and F. W. Schlegel (1772 - 1829) 17 Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767 – 1835) 17 August Schleicher 18 Neogrammarians (Junggrammatiker) 19 The name for a new linguistic field 20 Tasks 21 Summary 22 CHAPTER 3 Genealogical classification of languages 23 Tasks 28 Summary 32 CHAPTER 4 Phonological typology 33 Consonants and vowels 34 Syllables 36 Prosodic features 36 Tasks 38 Summary 40 CHAPTER 5 Morphological typology 41 Morphological classification of languages (holistic -

Linguistics 1A Morphology 2 Complex Words

Linguistics 1A Morphology 2 Complex words In the previous lecture we noted that words can be classified into different categories, such as verbs, nouns, adjectives, prepositions, determiners, and so on. We can make another distinction between word types as well, a distinction that cuts across these categories. Consider the verbs, nouns and adjectives in (1)-(3), respectively. It will probably be intuitively clear that the words in the (b) examples are complex in a way that the words in the (a) examples are not, and not just because the words in the (b) examples are, on the whole, longer. (1) a. to walk, to dance, to laugh, to kiss b. to purify, to enlarge, to industrialize, to head-hunt (2) a. house, corner, zebra b. collection, builder, sea horse (3) c. green, old, sick d. regional, washable, honey-sweet The words in the (a) examples in (1)-(3) do not have any internal structure. It does not seem to make much sense to say that walk , for example, consists of the smaller parts wa and lk . But for the words in the (b) examples this is different. These are built up from smaller parts that each contribute their own distinct bit of meaning to the whole. For example, builder consists of the verbal part build with its associated meaning, and the part –er that contributes a ‘doer’ reading, just as it does in kill-er , sell-er , doubt-er , and so on. Similarly, washable consists of wash and a part –able that contributes a meaning aspect that might be described loosely as ‘can be done’, as it does in refundable , testable , verifiable etc. -

Vs. Object Marker /Ta

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 7, pp. 1081-1092, July 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.7.1081-1092 On the Usage of Sinhalese Differential Object Markers Object Marker /wa/ vs. Object Marker /ta/ Kanduboda A, B. Prabath Ritsumeikan University, Ritsumeikan International, Global Gateway Program, Japan Abstract—Previous studies (Aisen, 2003; Kanduboda, 2011) on Sinhalese language have suggested that direct objects (i.e., accusative marked nouns) in active sentences can be marked by two distinctive case markers. In some sentences, accusative nouns can be denoted by the accusative case marker /wa/. In other sentences, the same nouns can again be denoted by the dative case marker /ta/. However, the verbs required by these accusatives were not investigated in the previous studies. Thus, the present study further conducted an investigation to observe whether these two types of case markings can occur with the same verbs. A free productivity task was conducted with 100 Sinhalese native speakers living in Sri Lanka. A comparison study was carried out using sentences with the verbs accompanying /wa/ accusatives and /ta/ accusatives. The results showed that, verbs accompanied by /wa/ case marker and verbs accompanied by /ta/ case marker are incongruent. Thus, this study concluded that Sinhalese active sentences consisting of transitive verbs are broadly divided into two patterns; those which take only /wa/ accusatives and those which take only /ta/ accusatives. Index Terms—Sinhalese language, active sentences, transitive verbs, /wa/ accusatives, /ta/ accusatives I. INTRODUCTION Sinhalese (also referred to as Sinhala, Singhala and Singhalese, (Englebretson & Carol, 2005)) is one of the major languages spoken in Sri Lanka. -

Words Their Way®: Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development

Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Words Their Way®: Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Introduction In this tutorial, we will learn about the stages of spelling development included in the professional development book titled, Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition. Copyright © 2017 by Pearson Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 1 Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Three Layers of English Orthography There are three layers of orthography, or spelling, in the English language-the alphabet layer, the pattern layer, and the meaning layer. Students' understanding of the layers progresses through five predictable stages of spelling development. Copyright © 2017 by Pearson Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 2 Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Alphabet Layer The alphabet layer represents a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds. In this layer, students use the sounds of individual letters to accurately spell words. Copyright © 2017 by Pearson Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 3 Words Their Way®: Word Study for Phonics, Vocabulary, and Spelling Instruction, Sixth Edition © 2016 Stages of Spelling Development Pattern Layer The pattern layer overlays the alphabet layer, as there are 42 to 44 sounds in English but only 26 letters in the alphabet. In this layer, students explore combinations of sound spellings that form visual and auditory patterns. Copyright © 2017 by Pearson Education, Inc. -

Number Systems in Grammar Position Paper

1 Language and Culture Research Centre: 2018 Workshop Number systems in grammar - position paper Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald I Introduction I 2 The meanings of nominal number 2 3 Special number distinctions in personal pronouns 8 4 Number on verbs 9 5 The realisation of number 12 5.1 The forms 12 5.2 The loci: where number is shown 12 5.3 Optional and obligatory number marking 14 5.4 The limits of number 15 5.4.1 Number and the meanings of nouns 15 5.4.2 'Minor' numbers 16 5.4.3 The limits of number: nouns with defective number values 16 6 Number and noun categorisation 17 7 Markedness 18 8 Split, or mixed, number systems 19 9 Number and social deixis 19 10 Expressing number through other means 20 11 Number systems in language history 20 12 Summary 21 Further readings 22 Abbreviations 23 References 23 1 Introduction Every language has some means of distinguishing reference to one individual from reference to more than one. Number reference can be coded through lexical modifiers (including quantifiers of various sorts or number words etc.), or through a grammatical system. Number is a referential property of an argument of the predicate. A grammatical system of number can be shown either • Overtly, on a noun, a pronoun, a verb, etc., directly referring to how many people or things are involved; or • Covertly, through agreement or other means. Number may be marked: • within an NP • on the head of an NP • by agreement process on a modifier (adjective, article, demonstrative, etc.) • through agreement on verbs, or special suppletive or semi-suppletive verb forms which may code the number of one or more verbal arguments, or additional marker on the verb.