Determining Gender Markedness in Wari' Joshua Birchall University Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

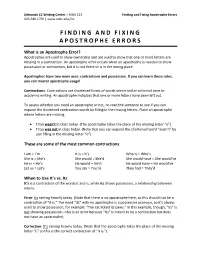

Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 |

Edmonds CC Writing Center | MUK 113 Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 | www.edcc.edu/lsc FINDING AND FIXING APOSTROPHE ERRORS What is an Apostrophe Error? Apostrophes are used to show ownership and are used to show that one or more letters are missing in a contraction. An apostrophe error occurs when an apostrophe is needed to show possession or contraction, but it is not there or is in the wrong place. Apostrophes have two main uses: contractions and possession. If you can learn these rules, you can master apostrophe usage! Contractions: Contractions are shortened forms of words which add an informal tone to academic writing. An apostrophe indicates that one or more letters have been left out. To assess whether you need an apostrophe or not, re-read the sentence to see if you can expand the shortened contraction words by filling in the missing letters. Place an apostrophe where letters are missing. Thao wasn’t in class today. (The apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter “o”). Thao was not in class today. (Note that you can expand the shortened word “wasn’t” by just filling in the missing letter “o”). These are some of the most common contractions: I am = I’m It is = It’s Who is = Who’s She is = She’s She would = She’d She would have = She would’ve He is = He’s He would = He’d He would have = He would’ve Let us = Let’s You are = You’re They had = They’d When to Use It’s vs. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

An Investigation of Possession in Moroccan Arabic

Family Agreement: An Investigation of Possession in Moroccan Arabic Aidan Kaplan Advisor: Jim Wood Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2017 Abstract This essay takes up the phenomenon of apparently redundant possession in Moroccan Arabic.In particular, kinship terms are often marked with possessive pronominal suffixes in constructions which would not require this in other languages, including Modern Standard Arabic. In the following example ‘sister’ is marked with the possessive suffix hā ‘her,’ even though the person in question has no sister. ﻣﺎ ﻋﻨﺪﻫﺎش ُﺧﺘﻬﺎ (1) mā ʿend-hā-sh khut-hā not at-her-neg sister-her ‘She doesn’t have a sister’ This phenomenon shows both intra- and inter-speaker variation. For some speakers, thepos- sessive suffix is obligatory in clausal possession expressing kinship relations, while forother speakers it is optional. Accounting for the presence of the ‘extra’ pronoun in (1) will lead to an account of possessive suffixes as the spell-out of agreement between aPoss◦ head and a higher element that contains phi features, using Reverse Agree (Wurmbrand, 2014, 2017). In regular pronominal possessive constructions, Poss◦ agrees with a silent possessor pro, while in sentences like (1), Poss◦ agrees with the PP at the beginning of the sentence that expresses clausal posses- sion. The obligatoriness of the possessive suffix for some speakers and its optionality forothers is explained by positing that the selectional properties of the D◦ head differ between speakers. In building up an analysis, this essay draws on the proposal for the construct state in Fassi Fehri (1993), the proposal that clitics are really agreement markers in Shlonsky (1997), and the account of clausal possession in Boneh & Sichel (2010). -

Adnominal Possession: Combining Typological and Second Language Perspectives

Adnominal possession: combining typological and second language perspectives Björn Hammarberg and Maria Koptjevskaja-Tamm 1. Introduction The notion of possession and its linguistic manifestations have been a popular topic in linguistic literature for a long time. What we will attempt here is to explore the domain of adnominal possession - pos- sessive relations and their manifestations within the noun phrase - in one particular language from two combined points of view: the ty- pological characteristics of the system, and the picture that emerges from second language learners' attempts to handle adnominal pos- session in production. We are focusing on Swedish, a language with a distinctive and rather elaborate system of adnominal possession. Our aim is twofold: to present an overview of how the Swedish sys- tem of adnominal possessive constructions works, and to show how acquisitional aspects connect with typological aspects in this domain. The English phrases Peter's hat, my son and a boy's leg all exem- plify prototypical cases of adnominal possession whereby one entity, the possessee, referred to by the head of the possessive noun phrase, is represented as possessed in one way or another by another entity, the possessor, referred to by the attribute. It has become a common- place in linguistics that possession is a difficult, if not impossible, notion to grasp (for a survey of adnominal possession in a cross- linguistic perspective cf. Koptjevskaja-Tamm 2001). However, even though it seems impossible to give a reasonable general definition for all the meanings covered by possessive constructions across lan- guages and even in one language, we can still provide criteria for identifying a possessive construction, or possessive constructions in a language. -

Serial Verb Constructions: Argument Structural Uniformity and Event Structural Diversity

SERIAL VERB CONSTRUCTIONS: ARGUMENT STRUCTURAL UNIFORMITY AND EVENT STRUCTURAL DIVERSITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Melanie Owens November 2011 © 2011 by Melanie Rachel Owens. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/db406jt2949 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Beth Levin, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Joan Bresnan I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Vera Gribanov Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Abstract Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) are constructions which contain two or more verbs yet behave in every grammatical respect as if they contain only one. -

Declension of Nouns

DECLENSION OF NOUNS In English, the relationship between words in a sentence depends primarily on word order. The difference between the god desires the girl and the girl desires the god is immediately apparent to us. Latin does not depend on word order for basic meaning, but on inflections (changes in the endings of words) to indicate the function of words within a sentence. Thus the god desires the girl can be expressed in Latin deus puellam desiderat, puellam deus desiderat, or desiderat puellam deus without any change in basic meaning. The accusative ending of puellam shows that the girl is being acted upon (i.e., is the object of the verb) and is not the actor (i.e., the subject of the verb). Similarly, the nominative form of deus shows that the god is the actor (agent) in the sentence, not the object of the verb. The inflection of nouns is called declension. The individual declensions are called cases, and together they form the case system. Nouns, pronouns, adjectives and participles are declined in six Cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and vocative and two Numbers (singular and plural). (The locative, an archaic case, existed in the classical period only for a few words). Nominative Indicates the subject of a sentence. (The boy loves the book). Genitive Indicates possession. (The boy loves the girl’s book). Dative Indicates indirect object. (The boy gave the book to the girl). Accusative Indicates direct object. (The boy loves the book). Ablative Answers the questions from where? by what means? how? from what cause? in what manner? when? or where? The ablative is used to show separation (from), instrumentality or means (by, with), accompaniment (with), or locality (at). -

"A/O Possession in Modern Maori" (2011)

Kenny Baclawski Maori Linguistics final paper A/O Possession in Modern Maori Kenneth Baclawski Linguistics 54: Maori Linguistics Professor James N. Stanford, Professor Margaret Mutu, Senior Lecturer Arapera Ngaha Dartmouth College, University of Auckland February 24th, 2011 1. Introduction Possession is a widely discussed topic in Polynesian Linguistics in part because of the complex dual system shared by most languages in the Polynesian family and retained largely unchanged until today. This possession system is represented by the notion of A/O possession: a dual possessive system with a strong semantic component, most often related as the presence or absence of control between possessor and possessee. Some linguists (Mutu, 2011) have alluded to the possibility of some levelling occurring in certain languages, but most point to a surprisingly strong retention throughout the Polynesian language family. Despite this supposed unity throughout Polynesia, linguists are less than unified in their interpretation of this possessive system. Wilson, for example quickly dismiss the idea that the Maori and Hawaiian systems exhibit an alienable/inalienable distinction (Wilson, 1982). Others, such as Schutz (on Maori, 1995) and Du Feu (on Rapa Nui, 1996), however, describe the system in exactly those terms. Understandably, authors such as Wilson resist the label of inalienability in order to suggest the semantic complexity underpinning the system. A cycle of complexity has thus been created in the literature, and most writings on Polynesian possession focus on the precise semantic motivation behind the synchronic possessive system. Few if any linguists, however, have considered the possessive system diachronically as a process of gradual levelling of a Proto-Polynesian possessive system that was most likely to a greater extent semantically motivated. -

Possession As a Lexical Relation: Evidence from the Hebrew Construct State* Daphna Heller Rutgers University

Possession as a Lexical Relation: Evidence from the Hebrew Construct State* Daphna Heller Rutgers University The literature on genitives (Partee 1997, Barker 1995) has generally assumed that the relation of possession (or ownership) is a special case of contextual relations. This has been challenged by Vikner & Jensen (in press) who analyze possession as a lexical relation. This paper presents an analysis of the construct state in Hebrew supporting the view that possession is a lexical relation. The head noun of the construct state is analyzed as a function from individuals into individuals (type <e,e>) that takes the genitive phrase as its argument. In accordance with Vikner & Jensen’s theory, an extra argument slot representing the genitive relation is lexically available for inherently relational nouns, and it is added to sortal nouns by a lexical rule. New data is provided to support the functional nature of the head noun and its restriction to lexical relations. 1. Introduction: The construct state in Hebrew Construct state nominals in Hebrew (and Arabic) have received much attention in the generative literature (Borer 1984, 1996, Ritter 1988, 1991, Siloni 1991, 1997, Dobrovie-Sorin 2000 among others). This genitive construction exhibits some unique properties that can be illustrated by comparing it to a second genitive construction, known as the free state. Compare the construct state (CS) in (1a) with the free state in (1b): (1) a. mapat ha-ir b. ha-mapa Sel ha-ir map the-city the-map of the-city both: ‘The city’s map’ (roughly) The two constructions exhibit the same word order – the head noun precedes the genitive phrase, but they differ in the form of their * For comments and helpful discussion I would like to thank the audience at WCCFL XXI, the participants of SURGE (the Rutgers semantics reading group), and Chris Barker, Ivano Caponigro, Shai Cohen, Veneeta Dayal, Heather Robinson, Gianluca Storto and Alex Zepter. -

A Crosslinguistic Verb-Sensitive Approach to Dative Verbs

LING 7800-009 CU Boulder Levin & Rappaport Hovav Summer 2011 Conceptual Categories and Linguistic Categories VI: A Crosslinguistic Verb-sensitive Approach to Dative Verbs 1 Revisiting possession • Lecture I briefly explored possession as a grammatically relevant component of meaning, • However, the approaches to event conceptualization examined so far have had little to say about this notion, with the exception of the localist approach: it takes possession to be a type of location. However, as we show here, the relation between the two notions with respect to argument realization is more complex than the localist approach suggests. • Key points about the nature of possession from Lecture I: — Possession is a relation between a possessor and a possessum—an entity over which the possessor exerts some form of control (e.g., Tham 2004). — The grammatically relevant notion of possession is quite broad (e.g., Heine 1997, Tham 2004): it encompasses instances of both alienable and inalienable possession, both abstract and concrete possessums, including types of information, but is insensitive to certain real life types of possession, such as legal possession. • The dative alternation was used to diagnose the presence of lexicalized possession: (1) a. Kim gave a ticket to tonight’s concert to Jill. (to variant) b. Kim gave Jill a ticket to tonight’s concert. (Double object variant) — give, a verb which lexicalizes nothing more than the causation of possession (e.g., Goldberg 1995, Jackendoff 1990, Pinker 1989), is perhaps THE canonical dative alternation verb. — The double object construction, which is specifically associated with the dative alternation, has an entailment which involves the (noncausative) verbs of possession have or get: (1b) entails (2).