Genericity and Definiteness in English and Spanish*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Definiteness Determined by Syntax: a Case Study in Tagalog 1 Introduction

Definiteness determined by syntax: A case study in Tagalog1 James N. Collins Abstract Using Tagalog as a case study, this paper provides an analysis of a cross-linguistically well attested phenomenon, namely, cases in which a bare NP’s syntactic position is linked to its interpretation as definite or indefinite. Previous approaches to this phenomenon, including analyses of Tagalog, appeal to specialized interpretational rules, such as Diesing’s Mapping Hypothesis. I argue that the patterns fall out of general compositional principles so long as type-shifting operators are available to the gram- matical system. I begin by weighing in a long-standing issue for the semantic analysis of Tagalog: the interpretational distinction between genitive and nominative transitive patients. I show that bare NP patients are interpreted as definites if marked with nominative case and as narrow scope indefinites if marked with genitive case. Bare NPs are understood as basically predicative; their quantificational force is determined by their syntactic position. If they are syntactically local to the selecting verb, they are existentially quantified by the verb itself. If they occupy a derived position, such as the subject position, they must type-shift in order to avoid a type-mismatch, generating a definite interpretation. Thus the paper develops a theory of how the position of an NP is linked to its interpretation, as well as providing a compositional treatment of NP-interpretation in a language which lacks definite articles but demonstrates other morphosyntactic strategies for signaling (in)definiteness. 1 Introduction Not every language signals definiteness via articles. Several languages (such as Russian, Kazakh, Korean etc.) lack articles altogether. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

Predicate Logic

Logical Form & Predicate Logic Jean Mark Gawron Linguistics San Diego State University [email protected] http://www.rohan.sdsu.edu/∼gawron Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 1/30 Predicates and Arguments Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 2/30 Logical Form The Logical Form of English sentences can be represented by formulae of Predicate Logic, What do we mean by the logical form of a sentence? We mean: we can capture the truth conditions of complex English expressions in predicate logic, given some account of the denotations (extensions) of the simple expressions (words). Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 3/30 The Leading Idea: Extensions Nouns, verbs, and adjectives have predicates as their translations. What does ’predicate’ mean? ’Predicate’ means what it means in predicate logic. Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 4/30 Intransitive verbs Translating into predicate logic (1) a. Johnwalks. b. walk(j) (2) a. [[j]] = John b. “The extension of ’j’ is the individual John.” c. [[walk]] = {x | x walks } d. “The extension of ’walk’ is the set of walkers” (3) a. [[John walks]] = [[walk(j)]] b. [[walk(j)]] = true iff [[j]] ∈ [[walk]] Logical Form & Predicate Logic – p. 5/30 Extensional denotations • Remember two kinds of denotation. For work with logic, denotations are always extensions. • We call a denotation such as [[walk]] (a set) an extension, because it is defined by the set of things the word walk describes or “extends over” • The denotation [[j]] is also extensional because it is defined by the individual the word John describes. • Next we extend extensional denotation to transitive verbs, nouns, and sentences. -

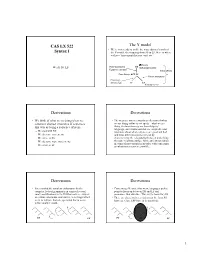

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Grammatical Gender and Grammatical Stems

Grammatical gender and grammatical stems How many grammatical genders exist in Czech? How can we tell the grammatical gender of a noun? What is a grammatical stem and how do we determine it? Why is knowing the grammatical stem important? How does the ending of a noun help us to know whether it is a hard- or soft-stem noun? Like other European languages (German, French, Spanish) but unlike English, Czech nouns are marked for grammatical gender. Czech has three grammatical genders: Masculine (M), Feminine (F), and Neuter (N). M and F partly overlap with the natural gender of human beings, so we have učitel for a male teacher and učitelka for a female teacher, sportovec for a male athlete and sportovkyně for a female athlete… But grammatical gender is a feature of all nouns (names of inanimate things, places, abstractions…), and it plays an important role in how Czech grammar works. To determine the grammatical gender of a noun (Maskulinum, femininum nebo neutrum?), we look at the ending—the last consonant or vowel—of the word in the Nominative singular (the basic or dictionary form of the word). 1. The great majority of nouns that end in a consonant are Masculine: profesor (professor), hrad (castle), stůl (table), pes (dog), autobus (bus), počítač (computer), čaj (tea), sešit (workbook), mobil (cell-phone)… Masculine nouns can be further divided into animate nouns (people and animals) and inanimate nouns (things, places, abstractions). 2. The great majority of nouns that end in -a are Feminine: profesorka (professor), lampa (lamp), kočka (cat), kniha (book), ryba (fish), fotka (photo), třída (classroom), podlaha (floor), budova (building)… 3. -

(2012) Perspectival Discourse Referents for Indexicals* Maria

To appear in Proceedings of SULA 7 (2012) Perspectival discourse referents for indexicals* Maria Bittner Rutgers University 0. Introduction By definition, the reference of an indexical depends on the context of utterance. For ex- ample, what proposition is expressed by saying I am hungry depends on who says this and when. Since Kaplan (1978), context dependence has been analyzed in terms of two parameters: an utterance context, which determines the reference of indexicals, and a formally unrelated assignment function, which determines the reference of anaphors (rep- resented as variables). This STATIC VIEW of indexicals, as pure context dependence, is still widely accepted. With varying details, it is implemented by current theories of indexicali- ty not only in static frameworks, which ignore context change (e.g. Schlenker 2003, Anand and Nevins 2004), but also in the otherwise dynamic framework of DRT. In DRT, context change is only relevant for anaphors, which refer to current values of variables. In contrast, indexicals refer to static contextual anchors (see Kamp 1985, Zeevat 1999). This SEMI-STATIC VIEW reconstructs the traditional indexical-anaphor dichotomy in DRT. An alternative DYNAMIC VIEW of indexicality is implicit in the ‘commonplace ef- fect’ of Stalnaker (1978) and is formally explicated in Bittner (2007, 2011). The basic idea is that indexical reference is a species of discourse reference, just like anaphora. In particular, both varieties of discourse reference involve not only context dependence, but also context change. The act of speaking up focuses attention and thereby makes this very speech event available for discourse reference by indexicals. Mentioning something likewise focuses attention, making the mentioned entity available for subsequent dis- course reference by anaphors. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Prosodic Focus∗

Prosodic Focus∗ Michael Wagner March 10, 2020 Abstract This chapter provides an introduction to the phenomenon of prosodic focus, as well as to the theory of Alternative Semantics. Alternative Semantics provides an insightful account of what prosodic focus means, and gives us a notation that can help with better characterizing focus-related phenomena and the terminology used to describe them. We can also translate theoretical ideas about focus and givenness into this notation to facilitate a comparison between frameworks. The discussion will partly be structured by an evaluation of the theories of Givenness, the theory of Relative Givenness, and Unalternative Semantics, but we will cover a range of other ideas and proposals in the process. The chapter concludes with a discussion of phonological issues, and of association with focus. Keywords: focus, givenness, topic, contrast, prominence, intonation, givenness, context, discourse Cite as: Wagner, Michael (2020). Prosodic Focus. In: Gutzmann, D., Matthewson, L., Meier, C., Rullmann, H., and Zimmermann, T. E., editors. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Semantics. Wiley{Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781118788516.sem133 ∗Thanks to the audiences at the semantics colloquium in 2014 in Frankfurt, as well as the participants in classes taught at the DGFS Summer School in T¨ubingen2016, at McGill in the fall of 2016, at the Creteling Summer School in Rethymnos in the summer of 2018, and at the Summer School on Intonation and Word Order in Graz in the fall of 2018 (lectures published on OSF: Wagner, 2018). Thanks also for in-depth comments on an earlier version of this chapter by Dan Goodhue and Lisa Matthewson, and two reviewers; I am also indebted to several discussions of focus issues with Aron Hirsch, Bernhard Schwarz, and Ede Zimmermann (who frequently wanted coffee) over the years. -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova.