REVIEWS Possession and Ownership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Shilluk Lexicography with Audio Data Bert Remijsen, Otto Gwado Ayoker & Amy Martin

Shilluk Lexicography With Audio Data Bert Remijsen, Otto Gwado Ayoker & Amy Martin Description This archive represents a resource on the lexicon of Shilluk, a Nilo-Saharan language spoken in South Sudan. It includes a table of 2530 lexicographic items, plus 10082 sound clips. The table is included in pdf and MS Word formats; the sound clips are in wav format (recorded with Shure SM10A headset mounted microphone and and Marantz PMD 660/661 solid state recorder, at a sampling frequency of 48kHz and a bit depth of 16). For each entry, we present: (a) the entry form (different for each word class, as explained below); (b) the orthographic representation of the entry form; (c) the paradigm forms and/or example(s); and (d) a description of the meaning. This collection was built up from 2013 onwards. The majority of entries were added between 2015 and 2018, in the context of the project “A descriptive analysis of the Shilluk language”, funded by the Leverhulme Trust (RPG-2015- 055). The main two methods through which the collection was built up are focused lexicography collection by semantic domain, whereby we would collect e.g. words relating to dwellings / fishing / etc., and text collection, whereby we would add entries as we came across new words in the course of the analysis of narrative text. We also added some words on the basis of two earlier lexicographic studies on Shilluk: Heasty (1974) and Ayoker & Kur (2016). We estimate that we drew a few hundred words from each. Comparing the lexicography resource presented here with these two resources, our main contribution is detail, in that we present information on the phonological form and on the grammatical paradigm. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

A Crossover Puzzle in Hindi Scrambling

Universität Leipzig November òýÔÀ A crossover puzzle in Hindi scrambling Stefan Keine University of Southern California (presenting joint work with Rajesh Bhatt) Ô Introduction Condition C, i.e., if it does not amnesty a Condition C violation in the base position (see Lebeaux ÔÀ, òýýý, Chomsky ÔÀÀç, Sauerland ÔÀÀ, Fox ÔÀÀÀ, • Background and terminology Takahashi & Hulsey òýýÀ). Ô. Inverse linking ( ) a. *He thinks [John’s mother] is intelligent. A possessor may bind a pronoun c-commanded by its host DP (May ÔÀÞÞ, Ô Ô b. * mother thinks is intelligent. Higginbotham ÔÀý, Reinhart ÔÀç). We will refer to this phenomena as [John’sÔ ]ò heÔ ò inverse linking (see May & Bale òýýâ for an overview). • Movement-type asymmetries (Ô) a. [Everyone’sÔ mother] thinks heÔ is a genius. English A- and A-movement dier w.r.t. several of these properties: b. [No one’s mother-in-law] fully approves of her . Ô Ô (â) Weak crossover (WCO) ò. Crossover a. A-movement Crossover arises if a DP moves over a pronoun that it binds and the resulting Every boyÔ seems to hisÔ mother [ Ô to be intelligent ] structure is ungrammatical (Postal ÔÀÞÔ, Wasow ÔÀÞò). b. A-movement (ò) Strong crossover (SCO): pronoun c-commands trace *Which boyÔ did hisÔ mother say [ Ô is intelligent ]? a. *DPÔ ... pronÔ ... tÔ (Þ) Secondary strong crossover (SSCO) b. *WhoÔ does sheÔ like Ô? a. A-movement (ç) Weak crossover (WCO): pronoun does not c-command trace [ Every boy’sÔ mother ]ò seems to himÔ [ ò to be intelligent ] a. *DP ... [ ... pron ...] ... t Ô DP Ô Ô b. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

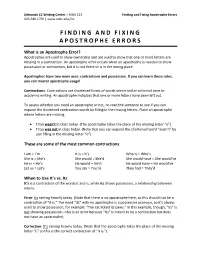

Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 |

Edmonds CC Writing Center | MUK 113 Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 | www.edcc.edu/lsc FINDING AND FIXING APOSTROPHE ERRORS What is an Apostrophe Error? Apostrophes are used to show ownership and are used to show that one or more letters are missing in a contraction. An apostrophe error occurs when an apostrophe is needed to show possession or contraction, but it is not there or is in the wrong place. Apostrophes have two main uses: contractions and possession. If you can learn these rules, you can master apostrophe usage! Contractions: Contractions are shortened forms of words which add an informal tone to academic writing. An apostrophe indicates that one or more letters have been left out. To assess whether you need an apostrophe or not, re-read the sentence to see if you can expand the shortened contraction words by filling in the missing letters. Place an apostrophe where letters are missing. Thao wasn’t in class today. (The apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter “o”). Thao was not in class today. (Note that you can expand the shortened word “wasn’t” by just filling in the missing letter “o”). These are some of the most common contractions: I am = I’m It is = It’s Who is = Who’s She is = She’s She would = She’d She would have = She would’ve He is = He’s He would = He’d He would have = He would’ve Let us = Let’s You are = You’re They had = They’d When to Use It’s vs. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

An Investigation of Possession in Moroccan Arabic

Family Agreement: An Investigation of Possession in Moroccan Arabic Aidan Kaplan Advisor: Jim Wood Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2017 Abstract This essay takes up the phenomenon of apparently redundant possession in Moroccan Arabic.In particular, kinship terms are often marked with possessive pronominal suffixes in constructions which would not require this in other languages, including Modern Standard Arabic. In the following example ‘sister’ is marked with the possessive suffix hā ‘her,’ even though the person in question has no sister. ﻣﺎ ﻋﻨﺪﻫﺎش ُﺧﺘﻬﺎ (1) mā ʿend-hā-sh khut-hā not at-her-neg sister-her ‘She doesn’t have a sister’ This phenomenon shows both intra- and inter-speaker variation. For some speakers, thepos- sessive suffix is obligatory in clausal possession expressing kinship relations, while forother speakers it is optional. Accounting for the presence of the ‘extra’ pronoun in (1) will lead to an account of possessive suffixes as the spell-out of agreement between aPoss◦ head and a higher element that contains phi features, using Reverse Agree (Wurmbrand, 2014, 2017). In regular pronominal possessive constructions, Poss◦ agrees with a silent possessor pro, while in sentences like (1), Poss◦ agrees with the PP at the beginning of the sentence that expresses clausal posses- sion. The obligatoriness of the possessive suffix for some speakers and its optionality forothers is explained by positing that the selectional properties of the D◦ head differ between speakers. In building up an analysis, this essay draws on the proposal for the construct state in Fassi Fehri (1993), the proposal that clitics are really agreement markers in Shlonsky (1997), and the account of clausal possession in Boneh & Sichel (2010). -

Determining Gender Markedness in Wari' Joshua Birchall University Of

Determining Gender Markedness in Wari’ Joshua Birchall University of Montana 1. Introduction Grammatical gender is rare across Amazonian languages. The language families that possess grammatical gender properties are Arawak, Chapakuran and Arawá. Wari’, a Chapakuran (Txapakura) language of Brazil, is unusual among these languages in that it possesses three gender categories: what we can refer to as masculine, feminine and neuter. While efforts have been made to posit the functionally unmarked gender in Arawak and Arawá languages, no such analysis has been given for any Chapakuran language. In this paper I propose that neuter is the functionally unmarked grammatical gender of Wari’. Aikhenvald (1999:84) states that masculine is the functionally unmarked gender for non-Caribbean Arawak languages, while Dixon (1999:298) claims that feminine is the unmarked gender in Arawá languages. Functionally unmarked gender refers to the gender that is obligatorily assigned when its designation is otherwise opaque. With attempts, as in Greenberg (1987), to claim a genetic relationship between Chapakuran languages and the Arawak and Arawá families, the presence of gender is a major grammatical similarity and possible motivating factor for such a hypothesis and thus should be examined. In order to investigate this claim, I first present an outline of the Wari’ gender distinctions and then proceed to describe how gender is manifested within the clause. A case is then presented for neuter as the functionally unmarked gender. This claim is further examined for its historical implications, especially regarding genetic affiliation. All of the data1 used in this paper come from Everett and Kern (1997). 2. Gender Distinctions The three gender distinctions we find in Wari’ are largely determined by the semantic domain of the noun. -

Publ 106271 Issue CH06 Page

REMARKS AND REPLIES 151 Focus on Cataphora: Experiments in Context Keir Moulton Queenie Chan Tanie Cheng Chung-hye Han Kyeong-min Kim Sophie Nickel-Thompson Since Chomsky 1976, it has been claimed that focus on a referring expression blocks coreference in a cataphoric dependency (*Hisi mother loves JOHNi vs. Hisi mother LOVES Johni). In three auditory experiments and a written questionnaire, we show that this fact does not hold when a referent is unambiguously established in the discourse (cf. Williams 1997, Bianchi 2009) but does hold otherwise, validating suggestions in Rochemont 1978, Horvath 1981, and Rooth 1985. The perceived effect of prosody, we argue, building on Williams’s original insight and deliberate experimental manipulation of Rochemont’s and Horvath’s examples, is due to the fact that deaccenting the R-expres- sion allows hearers to accommodate a salient referent via a ‘‘question under discussion’’ (Roberts 1996/2012, Rooth 1996), to which the pro- noun can refer in ambiguous or impoverished contexts. This heuristic is not available in the focus cases, and we show that participants’ interpretation of the pronoun is ambivalent here. Keywords: cataphora, focus, deaccenting, question under discussion 1 Focus and Cataphora Since Chomsky 1976, it has often been repeated that backward anaphora is blocked if the ‘‘anteced- ent’’ receives focus. This is illustrated by the purported contrast in the answers to the questions in (1). These examples, and judgments, are from Bianchi 2009.1 (1) a. As for John, who does his wife really love? ?*Hisi wife loves JOHNi. b. As for John, I believe his wife hates him. -

A Grammar of Umbeyajts As Spoken by the Ikojts People of San Dionisio Del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Salminen, Mikko Benjamin (2016) A grammar of Umbeyajts as spoken by the Ikojts people of San Dionisio del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/50066/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/50066/ A Grammar of Umbeyajts as spoken by the Ikojts people of San Dionisio del Mar, Oaxaca, Mexico Mikko Benjamin Salminen, MA A thesis submitted to James Cook University, Cairns In fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Language and Culture Research Centre, Cairns Institute College of Arts, Society and Education - James Cook University October 2016 Copyright Care has been taken to avoid the infringement of anyone’s copyrights and to ensure the appropriate attributions of all reproduced materials in this work. Any copyright owner who believes their rights might have been infringed upon are kindly requested to contact the author by e-mail at [email protected]. The research presented and reported in this thesis was conducted in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, 2007. The proposed research study received human ethics approval from the JCU Human Research Ethics Committee Approval Number H4268.