An Investigation of Possession in Moroccan Arabic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

A Phonological Effect of Phasal Boundaries in the Construct State Of

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Lingua 150 (2014) 315--331 www.elsevier.com/locate/lingua Where it’s [at]: A phonological effect of phasal boundaries in the construct state of Modern Hebrew Noam Faust * Hebrew University of Jerusalem Received 6 June 2013; received in revised form 31 July 2014; accepted 2 August 2014 Available online 15 September 2014 Abstract The consonant of the feminine marker /at/ of Modern Hebrew is absent from certain configurations, but present in others (N-at+N constructs). In this paper, I propose to regard this phenomenon a case of allomorphy, conditioned both phonologically and morpho- syntactically. The consonant is analyzed as floating. In consequence, additional skeletal support is needed to explain its realization. One possible, independently motivated source for such support is Lowenstamm’s (1996) ‘‘initial CV’’: the floating /t/ attaches to the initial CV of the following word. Still, the question is raised why this happens mainly in that very specific configuration. N-at+N constructions are therefore compared to the minimally different Nat+Adj, and four differences are singled-out. After a prosodic solution is judged insufficient, syntactic structures are proposed for both constructions and the four differences are related to phase-structure, under the assumption that D is the first phasal head of the nominal architecture. Adopting Scheer’s (2009) claim that Lowenstamm’s initial CV marks phase boundaries, rather than word-boundaries, it is then shown that the /t/ remains afloat exactly when the phase structure motivated by the four differences renders the initial CV of the following phase inaccessible; but if phase structure allows it, the same /t/ can be linked to that following CV. -

The Hebrew Construct State in an Endocentric Model of the NP

The Hebrew Construct State in an Endocentric Model of the NP Benjamin Bruening (University of Delaware) rough draft, January 5, 2021 Abstract Ritter (1991) is widely cited as having shown that Hebrew nominals require functional struc- ture like DP and Num(ber)P above the lexical NP (see, e.g., Preminger 2020). I demonstrate here that a very simple analysis is available in a model where the maximal projection of the nominal is a projection of the head N. This analysis posits very little movement and requires few auxiliary assumptions. Most dependents of N are simply base-generated in their surface positions. There is no need for functional projections like DP and NumP, and hence no argu- ment from Hebrew for their existence. 1 Basic Word Order: N and its Arguments Ritter (1991) is widely cited as having shown that Hebrew nominals require functional structure like DP and Num(ber)P above the lexical NP. Preminger (2020) illustrates the argument with the following non-derived noun that takes two arguments, an internal one (a PP) and an external one. In such cases, the order is N-S-O (noun-subject-object):1 (1) nic(a)xon ha-miflaga al yerive-ha victory.CS the-political.party(F) on rival.Pl.CS-3SgF.Poss ‘the victory of the political party over its rivals’ (Preminger 2020: (1a)) (Note that this possessive construction is known as the construct state, “CS” in the gloss; this will be important throughout this paper. The construct state has a head noun, here ‘victory’, followed immediately by a possessor; here the possessor is the external argument of the N, ‘the political party’.) The assumption behind the argument is that the noun and its internal argument (here the PP) combine first, and then the external argument combines with the constituent that results from that combination. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Our Hebrew Curriculum – NETA

BISHVIL HAIVRIT/ ADVANCED INTERMEDIATE ADVANCED BEGINNER BEGINNER SPEAK SPEAK SPEAK SPEAK In conversation about any topic in thirty In dialogue about school, family In a short 10-sentence dialogue In conversation on any topic in 20 sentences sentences or more entertainment in 15 sentences about daily life (holidays, school, -Give a short lecture on a theoretical topic -Speak in an interview schedule, etc.) -Express an opinion in 5-6 sentences WRITE WRITE WRITE WRITE -Personal or chronological report In standard modern Hebrew in various -In short notes (greeting, apology) -A paragraph on a personal topic -Short story adapted in elementary Hebrew forms of communication in 50-70 -In a personal letter of 15 sentences -A memo of 7-8 sentences sentences -In a 10 sentence announcement or request -An assertion of opinion in 5-6 sentences READ READ READ Press releases, journal articles, biblical READ Independently, original literary works (100- -An informative paragraph of 12-15 sentences verses, and short stories in elementary A 10- to 12- sentence 150 pages), Hebrew news articles, and -Comprehend a short story, poem or Hebrew (70-100 sentences) paragraph, description or folktale religious texts supported opinion LISTEN LISTEN LISTEN LISTEN Comprehend most components of a Comprehend short dialogue and Comprehend short dialogue Comprehend short dialogue and conversation of songs and on any topic about daily life (up to 24 sentences) or a about daily life, (up to 25 sentences) or a summarize informative lectures on places, among native speakers -

The Ongoing Eclipse of Possessive Suffixes in North Saami

Te ongoing eclipse of possessive sufxes in North Saami A case study in reduction of morphological complexity Laura A. Janda & Lene Antonsen UiT Te Arctic University of Norway North Saami is replacing the use of possessive sufxes on nouns with a morphologically simpler analytic construction. Our data (>2K examples culled from >.5M words) track this change through three generations, covering parameters of semantics, syntax and geography. Intense contact pressure on this minority language probably promotes morphological simplifcation, yielding an advantage for the innovative construction. Te innovative construction is additionally advantaged because it has a wider syntactic and semantic range and is indispensable, whereas its competitor can always be replaced. Te one environment where the possessive sufx is most strongly retained even in the youngest generation is in the Nominative singular case, and here we fnd evidence that the possessive sufx is being reinterpreted as a Vocative case marker. Keywords: North Saami; possessive sufx; morphological simplifcation; vocative; language contact; minority language 1. Te linguistic landscape of North Saami1 North Saami is a Uralic language spoken by approximately 20,000 people spread across a large area in northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland. North Saami is in a unique situation as the only minority language in Europe under intense pressure from majority languages from two diferent language families, namely Finnish (Uralic) in the east and Norwegian and Swedish (Indo-European 1. Tis research was supported in part by grant 22506 from the Norwegian Research Council. Te authors would also like to thank their employer, UiT Te Arctic University of Norway, for support of their research. -

Rule Based Morphological Analyzer of Kazakh Language

Rule Based Morphological Analyzer of Kazakh Language Gulshat Kessikbayeva Ilyas Cicekli Hacettepe University, Department of Hacettepe University, Department of Computer Engineering, Computer Engineering, Ankara,Turkey Ankara,Turkey [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Zaurbekov, 2013) and it only gives specific Having a morphological analyzer is a very alternation rules without generalized forms of critical issue especially for NLP related alternations. Here we present all generalized tasks on agglutinative languages. This paper forms of all alternation rules. Moreover, many presents a detailed computational analysis studies and researches have been done upon on of Kazakh language which is an morphological analysis of Turkic languages agglutinative language. With a detailed (Altintas and Cicekli, 2001; Oflazer, 1994; analysis of Kazakh language morphology, the formalization of rules over all Coltekin, 2010; Tantug et al., 2006; Orhun et al, morphotactics of Kazakh language is 2009). However there is no complete work worked out and a rule-based morphological which provides a detailed computational analyzer is developed for Kazakh language. analysis of Kazakh language morphology and The morphological analyzer is constructed this paper tries to do that. using two-level morphology approach with The organization of the rest of the paper is Xerox finite state tools and some as follows. Next section gives a brief implementation details of rule-based comparison of Kazakh language and Turkish morphological analyzer have been presented morphologies. Section 3 presents Kazakh vowel in this paper. and consonant harmony rules. Then, nouns with their inflections are presented in Section 4. 1 Introduction Section 4 also presents morphotactic rules for nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs and Kazakh language is a Turkic language which numerals. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Possessive Constructions in Najdi Arabic

Possessive Constructions in Najdi Arabic Eisa Sneitan Alrasheedi A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theoretical Linguistics School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics Newcastle University July, 2019 ii Abstract This thesis investigates the syntax of possession and agreement in Najdi Arabic (NA, henceforth) with a particular focus on the possession expressed at the level of the DP (Determiner Phrase). Using the main assumptions of the Minimalist Program (Chomsky 1995, and subsequent work) and adopting Abney’s (1987) DP-hypothesis, this thesis shows that the various agreement patterns within the NA DP can be accounted for with the use of a probe/goal agreement operation (Chomsky 2000, 2001). Chapter two discusses the syntax of ‘synthetic’ possession in NA. Possession in NA, like other Arabic varieties, can be expressed synthetically using a Construct State (CS), e.g. kitaab al- walad (book the-boy) ‘the boy’s book’. Drawing on the (extensive) literature on the CS, I summarise its main characteristics and the different proposals for its derivation. However, the main focus of this chapter is on a lesser-investigated aspect of synthetic possession – that is, possessive suffixes, the so-called pronominal possessors, as in kitaab-ah (book-his) ‘his book’. Building on a previous analysis put forward by Shlonsky (1997), this study argues (contra Fassi Fehri 1993), that possessive suffixes should not be analysed as bound pronouns but rather as an agreement inflectional suffix (à la Shlonsky 1997), where the latter is derived by Agree between the Poss(essive) head and the null pronoun within NP. -

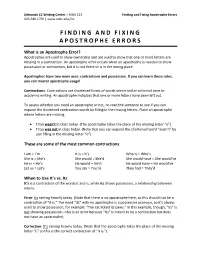

Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 |

Edmonds CC Writing Center | MUK 113 Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 | www.edcc.edu/lsc FINDING AND FIXING APOSTROPHE ERRORS What is an Apostrophe Error? Apostrophes are used to show ownership and are used to show that one or more letters are missing in a contraction. An apostrophe error occurs when an apostrophe is needed to show possession or contraction, but it is not there or is in the wrong place. Apostrophes have two main uses: contractions and possession. If you can learn these rules, you can master apostrophe usage! Contractions: Contractions are shortened forms of words which add an informal tone to academic writing. An apostrophe indicates that one or more letters have been left out. To assess whether you need an apostrophe or not, re-read the sentence to see if you can expand the shortened contraction words by filling in the missing letters. Place an apostrophe where letters are missing. Thao wasn’t in class today. (The apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter “o”). Thao was not in class today. (Note that you can expand the shortened word “wasn’t” by just filling in the missing letter “o”). These are some of the most common contractions: I am = I’m It is = It’s Who is = Who’s She is = She’s She would = She’d She would have = She would’ve He is = He’s He would = He’d He would have = He would’ve Let us = Let’s You are = You’re They had = They’d When to Use It’s vs. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

Determining Gender Markedness in Wari' Joshua Birchall University Of

Determining Gender Markedness in Wari’ Joshua Birchall University of Montana 1. Introduction Grammatical gender is rare across Amazonian languages. The language families that possess grammatical gender properties are Arawak, Chapakuran and Arawá. Wari’, a Chapakuran (Txapakura) language of Brazil, is unusual among these languages in that it possesses three gender categories: what we can refer to as masculine, feminine and neuter. While efforts have been made to posit the functionally unmarked gender in Arawak and Arawá languages, no such analysis has been given for any Chapakuran language. In this paper I propose that neuter is the functionally unmarked grammatical gender of Wari’. Aikhenvald (1999:84) states that masculine is the functionally unmarked gender for non-Caribbean Arawak languages, while Dixon (1999:298) claims that feminine is the unmarked gender in Arawá languages. Functionally unmarked gender refers to the gender that is obligatorily assigned when its designation is otherwise opaque. With attempts, as in Greenberg (1987), to claim a genetic relationship between Chapakuran languages and the Arawak and Arawá families, the presence of gender is a major grammatical similarity and possible motivating factor for such a hypothesis and thus should be examined. In order to investigate this claim, I first present an outline of the Wari’ gender distinctions and then proceed to describe how gender is manifested within the clause. A case is then presented for neuter as the functionally unmarked gender. This claim is further examined for its historical implications, especially regarding genetic affiliation. All of the data1 used in this paper come from Everett and Kern (1997). 2. Gender Distinctions The three gender distinctions we find in Wari’ are largely determined by the semantic domain of the noun.