AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Strategy of Case-Marking

Case marking strategies Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov1 Radboud University Nijmegen DRAFT January 2006 Abstract Two strategies of case marking in natural languages are discussed. These are defined as two violable constraints whose effects are shown to converge in the case of differential object marking but diverge in the case of differential subject marking. The strength of the case bearing arguments will be shown to be of utmost importance for case marking as well as voice alternations. The strength of arguments can be viewed as a function of their discourse prominence. The analysis of the case marking patterns we find cross-linguistically is couched in a bidirectional OT analysis. 1. Assumptions In this section we wish to put forward our three basic assumptions: (1) In ergative-absolutive systems ergative case is assigned to the first argument x of a two-place relation R(x,y). (2) In nominative-accusative systems accusative case is assigned to the second argument y of a two-place relation R(x,y). (3) Morphologically unmarked case can be the absence of case. The first two assumptions deal with the linking between the first (highest) and second (lowest) argument in a transitive sentence and the type of case marking. For reasons of convenience, we will refer to these arguments quite sloppily as the subject and the object respectively, although we are aware of the fact that the labels subject and object may not be appropriate in all contexts, dependent on how they are actually defined. In many languages, ergative and accusative case are assigned only or mainly in transitive sentences, while in intransitive sentences ergative and accusative case are usually not assigned. -

Appendix a PCC Protocol Death Senior National Figure.Pdf

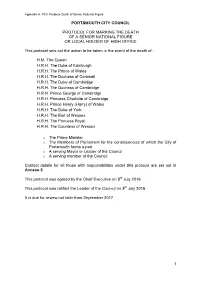

Appendix A: PCC Protocol Death of Senior National Figure PORTSMOUTH CITY COUNCIL PROTOCOL FOR MARKING THE DEATH OF A SENIOR NATIONAL FIGURE OR LOCAL HOLDER OF HIGH OFFICE This protocol sets out the action to be taken in the event of the death of: H.M. The Queen H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh H.R.H. The Prince of Wales H.R.H. The Duchess of Cornwall H.R.H. The Duke of Cambridge H.R.H. The Duchess of Cambridge H.R.H. Prince George of Cambridge H.R.H. Princess Charlotte of Cambridge H.R.H. Prince Henry (Harry) of Wales H.R.H. The Duke of York H.R.H. The Earl of Wessex H.R.H. The Princess Royal H.R.H. The Countess of Wessex o The Prime Minister o The Members of Parliament for the constituencies of which the City of Portsmouth forms a part o A serving Mayor or Leader of the Council o A serving member of the Council Contact details for all those with responsibilities under this protocol are set out in Annexe 5 This protocol was agreed by the Chief Executive on 8th July 2016 This protocol was ratified the Leader of the Council on 8th July 2016 It is due for review not later than September 2017 1 Appendix A: PCC Protocol Death of Senior National Figure PART 1 Implementation of the Protocol on hearing of the death Action required Authorised by Other Notes Portsmouth City Council’s Implementation will be The implementing officer mourning Protocol will be authorised by the Chief will arrange for flags to be implemented on the formal Executive or Assistant lowered immediately and announcement of the Chief Executive for books of condolence to be death of any one of those implementation by Claire opened on the next persons named on page 1 Looney, Partnership & working day. -

Sinitic Languages of Northwest China: Where Did Their Case Marking Come From?* Dan Xu

Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?* Dan Xu To cite this version: Dan Xu. Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?*. Cao, Djamouri and Peyraube. Languages in contact in Northwestern China, 2015. hal-01386250 HAL Id: hal-01386250 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01386250 Submitted on 31 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?* XU DAN 1. Introduction In the early 1950s, Weinreich (1953) published a monograph on language contact. Although this subject drew the attention of a few scholars, at the time it remained marginal. Over two decades, several scholars including Moravcsik (1978), Thomason and Kaufman (1988), Aikhenvald (2002), Johanson (2002), Heine and Kuteva (2005) and others began to pay more attention to language contact. As Thomason and Kaufman (1988: 23) pointed out, language is a system, or even a system of systems. Perhaps this is why previous studies (Sapir, 1921: 203; Meillet 1921: 87) indicated that grammatical categories are not easily borrowed, since grammar is a system. -

Handbook on Sensitive Practice for Health Care Practitioners

Handbook on Sensitive Practice for Health Care Practitioners: Lessons from Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse Handbook on Sensitive Practice for Health Care Practitioners: Lessons from Adult Survivors of Child- hood Sexual Abuse was researched and written by Candice L. Schachter, Carol A. Stalker, Eli Teram, Gerri C. Lasiuk and Alanna Danilkewich Également en français sous le titre Manuel de pratique sensible à l’intention des professionnels de la santé – Leçons tirées des personnes qui ont été victimes de violence sexuelle durant l’enfance The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada. Contents may not be reproduced for commercial purposes, but any other reproduction, with acknowledgements, is encouraged. Recommended citation: Schachter, C.L., Stalker, C.A., Teram, E., Lasiuk, G.C., Danilkewich, A. (2008). Handbook on sensitive practice for health care practitioner: Lessons from adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada. This publication may be provided in alternate formats upon request. For further information on family violence issues please contact: National Clearinghouse on Family Violence Family Violence Prevention Unit Public Health Agency of Canada 200 Eglantine Driveway Jeanne Mance Building, 1909D, Tunney’s Pasture Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K9 Telephone: 1-800-267-1291 or (613) 957-2938 Fax: (613) 941-8930 TTY: 1-800-561-5643 or (613) 952-6396 Web site: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/nc-cn E-mail: [email protected] © 2009 Candice L. Schachter, Carol A. Stalker, Eli Teram, Gerri C. -

2 Race, Class, and Residence in the Chicago Ummah

2 Race, Class, and Residence in the Chicago Ummah Ethnic Muslim Spaces and American Muslim Discourses The racial landscape of a city influences how close American Muslims have come to fulfilling the ummah ideals there. When I arrived in Chicago in the spring of 2002 to research Muslims in the city, two things stood out. One was the city’s diversity. Chicago was a nexus of global flows. Filled with people from all over the world—Bosnians, Mexicans, Nigerians, and Vietnamese—Chicago fit my idea of a global village. But alongside these global flows were major inequalities, particularly in the racially segregated housing, the second thing that stood out. Indeed, Chicago has always been known for its racist residential patterns and ethnic neighborhoods. “Germans settled on the North Side, Irish on the South Side, Jews on the West Side, Bohemians and Poles on the Near Southwest Side.”1 In the nineteenth century, European immigrants carved out ethnic lines across the city which, with the rise of black migration to Chicago in the 1920s, soon had viciously racist and economically devastating consequences. Fear and widespread propaganda created large-scale white resistance to African Americans. As whites maneuvered to keep blacks out of their neighborhoods and fled from the ones where blacks did settle, African Americans were confined to and concentrated in the South Side’s Black Belt. Business owners then moved from this expanding black area and invested their resources and profits elsewhere. As the community’s resources declined and the population grew, neighborhoods in the Black Belt steadily turned into overcrowded slums.2 Outside the South Side’s Black Belt, a flourishing metropolis took form, setting the stage for Chicago to become a major international city. -

Long Corner Kicks in the English Premier League

Pulling, C.: LONG CORNER KICKS IN THE ENGLISH PREMIER LEAGUE... Kinesiology 47(2015)2:193-201 LONG CORNER KICKS IN THE ENGLISH PREMIER LEAGUE: DELIVERIES INTO THE GOAL AREA AND CRITICAL AREA Craig Pulling Department of Adventure Education and Physical Education, University of Chichester, England, United Kingdom Original scientific paper UDC: 796.332.012 Abstract: The purpose of this study was to investigate long corner kicks within the English Premier League that entered either the goal area (6-yard box) or the critical area (6-12 yards from the goal-line in the width of the goal area) with the defining outcome occurring after the first contact. A total of 328 corner kicks from 65 English Premier League games were analysed. There were nine goals scored from the first contact (2.7%) where the ball was delivered into either the goal area or the critical area. There was a significant association between the area the ball was delivered to and the number of attempts at goal (p<.03), and the area the ball was delivered to and the number of defending outcomes (p<.01). The results suggest that the area where a long corner kick is delivered to will influence how many attempts at goal can be achieved by the attacking team and how many defensive outcomes can be conducted by the defensive team. There was no significant association between the type of delivery and the number of attempts at goal from the critical area (p>.05). It appears as though the area of delivery is more important than the type of delivery for achieving attempts at goal from long corner kicks; however, out of the nine goals observed within this study, seven came from an inswinging delivery. -

Possessive Constructions in Modern Low Saxon

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN MODERN LOW SAXON a thesis submitted to the department of linguistics of stanford university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of arts Jan Strunk June 2004 °c Copyright by Jan Strunk 2004 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Joan Bresnan (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Tom Wasow I certify that I have read this thesis and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Dan Jurafsky iii iv Abstract This thesis is a study of nominal possessive constructions in modern Low Saxon, a West Germanic language which is closely related to Dutch, Frisian, and German. After identifying the possessive constructions in current use in modern Low Saxon, I give a formal syntactic analysis of the four most common possessive constructions within the framework of Lexical Functional Grammar in the ¯rst part of this thesis. The four constructions that I will analyze in detail include a pronominal possessive construction with a possessive pronoun used as a determiner of the head noun, another prenominal construction that resembles the English s-possessive, a linker construction in which a possessive pronoun occurs as a possessive marker in between a prenominal possessor phrase and the head noun, and a postnominal construction that involves the preposition van/von/vun and is largely parallel to the English of -possessive. -

The Case of Restricted Locatives Ora Matushansky

The case of restricted locatives Ora Matushansky To cite this version: Ora Matushansky. The case of restricted locatives. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung , 2019, 23 (2), 10.18148/sub/2019.v23i2.604. halshs-02431372 HAL Id: halshs-02431372 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02431372 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The case of restricted locatives1 Ora MATUSHANSKY — SFL (CNRS/Université Paris-8)/UiL OTS/Utrecht University Abstract. This paper examines the cross-linguistic phenomenon of locative case restricted to a closed class of items (L-nouns). Starting with Latin, I suggest that the restriction is semantic in nature: L-nouns denote in the spatial domain and hence can be used as locatives without further material. I show how the independently motivated hypothesis that directional PPs consist of two layers, Path and Place, explains the directional uses of L-nouns and the cases that are assigned then, and locate the source of the locative case itself in p0, for which I then provide a clear semantic contribution: a type-shift from the domain of loci to the object domain. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Towards Licensing of Adverbial Noun Phrases in HPSG

Towards Licensing of Adverbial Noun Phrases in HPSG Beata Trawinski University of Tubingen¨ Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar Center for Computational Linguistics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2004 CSLI Publications pages 294–312 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2004 Trawinski, Beata. 2004. Towards Licensing of Adverbial Noun Phrases in HPSG. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Head- Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Center for Computational Linguistics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 294–312. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract This paper focuses on aspects of the licensing of adverbial noun phrases (AdvNPs) in the HPSG grammar framework. In the first part, empirical is- sues will be discussed. A number of AdvNPs will be examined with respect to various linguistic phenomena in order to find out to what extent AdvNPs share syntactic and semantic properties with non-adverbial NPs. Based on empirical generalizations, a lexical constraint for licensing both AdvNPs and non-adverbial NPs will be provided. Further on, problems of structural li- censing of phrases containing AdvNPs that arise within the standard HPSG framework of Pollard and Sag (1994) will be pointed out, and a possible solution will be proposed. The objective is to provide a constraint-based treatment of NPs which describes non-redundantly both their adverbial and non-adverbial usages. The analysis proposed in this paper applies lexical and phrasal implicational constraints and does not require any radical mod- ifications or extensions of the standard HPSG geometry of Pollard and Sag (1994). Since adverbial NPs have particularly high frequency and a wide spec- trum of uses in inflectional languages such as Polish, we will take Polish data into consideration. -

How Do Young Children Acquire Case Marking?

INVESTIGATING FINNISH-SPEAKING CHILDREN’S NOUN MORPHOLOGY: HOW DO YOUNG CHILDREN ACQUIRE CASE MARKING? Thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences 2015 HENNA PAULIINA LEMETYINEN SCHOOL OF PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCES 2 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. 8 DECLARATION .......................................................................................................................... 9 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT .......................................................................................................... 9 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: General introduction to language acquisition research ...................................... 11 1.1. Generativist approaches to child language............................................................ 11 1.2. Usage-based approaches to child language........................................................... 14 1.3. The acquisition of morphology ............................................................................. -

Morphological Causatives Are Voice Over Voice

Morphological causatives are Voice over Voice Yining Nie New York University Abstract Causative morphology has been associated with either the introduction of an event of causation or the introduction of a causer argument. However, morphological causatives are mono-eventive, casting doubt on the notion that causatives fundamentally add a causing event. On the other hand, in some languages the causative morpheme is closer to the verb root than would be expected if the causative head is responsible for introducing the causer. Drawing on evidence primarily from Tagalog and Halkomelem, I argue that the syntactic configuration for morphological causatives involves Voice over Voice, and that languages differ in whether their ‘causative marker’ spells out the higher Voice, the lower Voice or both. Keywords: causative, Voice, argument structure, morpheme order, typology, Tagalog 1. Introduction Syntactic approaches to causatives generally fall into one of two camps. The first view builds on the discovery that causatives may semantically consist of multiple (sub)events (Jackendoff 1972, Dowty 1979, Parsons 1990, Levin & Rappaport Hovav 1994, a.o.). Consider the following English causative–anticausative pair. The anticausative in (1a) consists of an event of change of state, schematised in (1b). The causative in (2a) involves the same change of state plus an additional layer of semantics that conveys how that change of state is brought about (2b). (1) a. The stick broke. b. [ BECOME [ stick STATE(broken) ]] (2) a. Pat broke the stick. b. [ Pat CAUSE [ BECOME [ stick STATE(broken) ]]] Word Structure 13.1 (2020): 102–126 DOI: 10.3366/word.2020.0161 © Edinburgh University Press www.euppublishing.com/word MORPHOLOGICAL CAUSATIVES ARE VOICE OVER VOICE 103 Several linguists have proposed that the semantic CAUSE and BECOME components of the causative are encoded as independent lexical verbal heads in the syntax (Harley 1995, Cuervo 2003, Folli & Harley 2005, Pylkkänen 2008, a.o.).