Why Was the Story of Arash-I Kamangir Excluded from the Shahnameh?” Iran Nameh, 29:2 (Summer 2014), 42-63

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

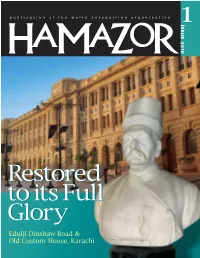

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Gènes Et Mythes Littéraires : Pour Un Modèle Biologique Du Dynamisme Mythique

G`eneset mythes litt´eraires: pour un mod`elebiologique du dynamisme mythique Abolghasem Ghiasizarch To cite this version: Abolghasem Ghiasizarch. G`eneset mythes litt´eraires: pour un mod`elebiologique du dy- namisme mythique. Litt´eratures. Universit´eGrenoble Alpes, 2011. Fran¸cais. <NNT : 2011GRENL001>. <tel-00596834> HAL Id: tel-00596834 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00596834 Submitted on 30 May 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE GRENOBLE Spécialité : Imaginaire Arrêté ministériel : 7 août 2006 Présentée par « Abol Ghasem / GHIASIZARCH » Thèse dirigée par « Philippe / WALTER » préparée au sein du Laboratoire CRI – Centre de Recherche sur l’Imaginaire (EA 610) dans l'École Doctorale Langues, Littératures et Sciences Humaines GÈNES ET MYTHES LITTÉRAIRES : POUR UN MODÈLE BIOLOGIQUE DU DYNAMISME MYTHIQUE Thèse soutenue publiquement le « 14 janvier 2011», devant le jury composé de : M. Jean Bruno RENARD Professeur à l’Université Montpellier 3, Président M. Claude THOMASSET Professeur à l’Université Paris IV Sorbonne, Rapporteur M. Philippe WALTER Professeur à l’Université Grenoble 3, Membre GÈNES ET MYTHES LITTÉRAIRES : POUR UN MODÈLE BIOLOGIQUE DU DYNAMISME MYTHIQUE 2 REMERCIEMENT Qui ne remercie pas le peuple, ne remercie pas Dieu non plus. -

Nnnnãvr-N Paznû

THE MANUSCRTpTs or ð¿Nen ¿NenÃðn-N,iua n¡vn ;n¿j vt-vI nà r-NÃtw ø BY zARToSr-n nnnnÃvr-n paZnû Olga Yastrebova Zarto$t-e Bahrãm was a Zoroastrian poet who lived in Iran in the late 13th century. He is one of the few Zoroastrian authors who wrote in Persian and whose name and scraps of biographical information have been preserved to our days. The most significant and well known of his works are Ardãya-Wrãf-nãmet, ëangranghãðe' nãme2, andQesse-ye 'lJmar Xattãb va iãhzdde'ye irãn-zamr-n3, a collection of parables on the perishable nature of this world.a All of them were written in hazaj- e mosaddas metre. For several centuries tradition ascribed to him the authorship of Zarto!çnãme (onginally Mowlûd-Zartoflt)s, but as Ch. Rempis and R. Ahfi showed in their studies published independently in 1963 and 1964, the real author was another Zoroastrian, named Kay-Kâüs b. Kay-Xosrow b. Dãrã, from the city of Ray.6 The episode of Zaratustra's biography which is the subject of Õangranghãëe- nãme, is nol found in any other source except this poem. After Zaratu$tra's religion had been successfully disseminated in the kingdom of Go5tasp, the news reached the Indian sage Õangranghãðe. This wise man is said to have been one of the teachers of GoStasp's famous counsellor Jãmãsp. ðangranghaðe summoned Zarto5t to take part in a dispute, and spent two years preparing for it. He devoted all his time to gathering difficult questions and riddles. After the long period of I Text published twice: Jamasp Asa 1902; Afift 1964. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Comparison of Arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh Based on the Ancient Story of Bahmannameh

Propósitos y Representaciones May. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(3), e1092 ISSN 2307-7999 Current context of education and psychology in Europe and Asia e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1092 RESEARCH NOTES Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh Comparación de la arrogancia en Shahnameh y Bahmannameh basada en la antigua historia de Bahmannameh Zohreh Amiri PhD student in Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Reza Ashrafzadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Mohammad Shah Badiezadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Received 07-08-20 Revised 08-10-20 Accepted 09-02-20 On line 03-06-21 *Correspondence Cite as: Email: [email protected] Amiri, Z., Ashrafzadeh, R., & Shah Badiezadeh, M. (2021). Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(SPE3), e1092. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1092 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2021. Este artículo se distribuye bajo licencia CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Internacional (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh Summary One of the most important aspects of the struggle of warriors and warriors in epic works is the arrogance that is called by the comrades before the start of the hand-to-hand battle. It is accompanied by pride in ancestry, race, and ridicule. -

L2/20-246 Teeth and Bellies: a Proposed Model for Encoding Book Pahlavi

L2/20-246 Teeth and bellies: a proposed model for encoding Book Pahlavi Roozbeh Pournader (WhatsApp) September 7, 2020 Background In Everson 2002, a proposal was made to encode a unified Avestan and Pahlavi script in the Unicode Standard. The proposal went through several iterations, eventually leading to a separate encoding of Avestan as proposed by Everson and Pournader 2007a, in which Pahlavi was considered non-unifiable with Avestan due to its cursive joining property. The non-cursive Inscriptional Pahlavi (Everson and Pournader 2007b) and the cursive Psalter Pahlavi (Everson and Pournader 2011) were later encoded too. But Book Pahlavi, despite several attempts (see the Book Pahlavi Topical Document list at https://unicode.org/L2/ topical/bookpahlavi/), remains unencoded. Everson 2002 is peculiar among earlier proposals by proposing six Pahlavi archigraphemes, including an ear, an elbow, and a belly. I remember from conversations with Michael Everson that he intended these to be used for cases when a scribe was just copying some text without understanding the underlying letters, considering the complexity of the script and the loss of some of its nuances to later scribes. They could also be used when modern scholars wanted to represent a manuscript as written, without needing to over-analyze potentially controversial readings. Meyers 2014 takes such a graphical model to an extreme, trying to encode pieces of the writing system, most of which have some correspondence to letters, but with occasional partial letters (e.g. PARTIAL SHIN and FINAL SADHE-PARTIAL PE). Unfortunately, their proposal rejects joining properties for Book Pahlavi and insists that “[t]he joining behaviour of the final stems of the characters in Book Pahlavi is more similar to cursive variants of Latin than to Arabic”. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

NEWSLETTER CENTER for IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol

CIS NEWSLETTER CENTER FOR IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 13, No.2 MEALAC–Columbia University–New York Fall 2001 Encyclopædia Iranica: Volume X Published Fascicle 1, Volume XI in Press With the publication of fascicle ISLAMIC PERSIA: HISTORY AND 6 in the Summer of 2001, Volume BIOGRAPHY X of the Encyclopædia Iranica was Eight entries treat Persian his- completed. The first fascicle of Vol- tory from medieval to modern ume XI is in press and will be pub- times, including “Golden Horde,” lished in December 2001. The first name given to the Mongol Khanate fascicle of volume XI features over 60 ruled by the descendents of Juji, the articles on various aspects of Persian eldest son of Genghis Khan, by P. Jack- culture and history. son. “Golshan-e Morad,” a history of the PRE-ISLAMIC PERSIA Zand Dynasty, authored by Mirza Mohammad Abu’l-Hasan Ghaffari, by J. Shirin Neshat Nine entries feature Persia’s Pre-Is- Perry. “Golestan Treaty,” agreement lamic history and religions: “Gnosti- arranged under British auspices to end at Iranian-American Forum cism” in pre-Islamic Iranian world, by the Russo-Persian War of 1804-13, by K. Rudolph. “Gobryas,” the most widely On the 22nd of September, the E. Daniel. “Joseph Arthur de known form of the old Persian name Encyclopædia Iranica’s Iranian-Ameri- Gobineau,” French man of letters, art- Gaub(a)ruva, by R. Schmitt. “Giyan ist, polemist, Orientalist, and diplomat can Forum (IAF) organized it’s inau- Tepe,” large archeological mound lo- who served as Ambassador of France in gural event: a cocktail party and pre- cated in Lorestan province, by E. -

Iran's Holiday Calendar

IRAN’S HOLIDAY CALENDAR 2016 January 2016 Your Travel Companion 1 goingIRAN wants you to see, read, and know everything about Iran. Ask us about all your needs. goingIRAN strives to acquaint Iranian art and culture with audiences abroad. COPYRIGHT All of the published content on this e-Booklet have all rights reserved. All goingIRAN content, logos and graphic designs of this e-Booklet are property of the Web Gasht Nameh Company. Solely Web Gasht Nameh holds the right to publish and use the formerly stated material. Any use of the goingIRAN graphics (logo, content, design) may only happen through the written request of the user and the ac- ceptance of goingIRAN. Upon our realization of any violation of goingIRAN’s rights, legal action will be taken. IRAN’S HOLIDAY CALENDAR Author: Rojan Hemmati & Alireza Sattari (Sourced From an authentic 2016 Iranian Calendar) Central Office: Tehran-IRAN Post code: 1447893713 Designed by Studio TOOL www.goingiran.com [email protected] 2 Aside from the national holidays that follow the Persian Solar Calendar, many of Iran’s holidays are in accordance with events in the Islamic religion and follow the Mus- lim Lunar Calendar, which moves about 10 days forward each year. A few examples of Iranian holidays are: Iranian New Year (Nowruz): Celebrated on the first day of spring, this date has been the mark of the New Year for over 5,000 years throughout several ancient cultures. It embraces the spring equinox and has been celebrated in the same unique Iranian way for the past 3,000 years. It is also deeply rooted in the Zoroastrian belief system. -

Arash Zeini 8Th May 2020

Response to ‘Next steps on Book Pahlavi’ (L2/20-135) Arash Zeini 8th May 2020 Introduction Pournader & Hai (2020) might be right in saying that ‘Book Pahlavi may be the best-known complex script not yet encoded in Unicode’. However, I am inclined to add that Book Pahlavi is certainly one of the least researched and understood scripts of late antiquity. Much work is needed before we can make reliable statements about the palaeography of Book Pahlavi. The issues that have puzzled the Unicode experts are in part genuinely difficult to answer. But in my view, the wrong questions have also been asked at times.1 In this document I will attempt to answer the questions raised by Pournader & Hai (2020) which is a very welcome addition to the proposals as it consolidates the questions that have remained unanswered. Please note that my rendering of Middle Persian words and Pahlavi characters is limited by the possibilities offered by the available fonts, which are not designed to accurately represent the scribal idiosyncrasies. If any representations raise more questions, please contact me for clarifications. Question 1 yh/1: The MP suffix -īh, transliterated <-yh>, is written / in Book Pahlavi. Contrary to Meyers (2014:12), the correct analysis of / is ! + + or $ + -. Some- times the scribes abbreviate or rather simplify this sequence of characters to . This happens most commonly at the end of the line, and not in everymanu- script. It is, for instance, very rare in manuscripts of the Pahlavi Yasna. Meyers 1See, for instance, Pournader & Hai (2020:6) on the issue of <b> as raised by Meyers (2014). -

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan 著者 Ubaidulloev Zubaidullo journal or The bulletin of Faculty of Health and Sport publication title Sciences volume 38 page range 43-58 year 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00126173 筑波大学体育系紀要 Bull. Facul. Health & Sci., Univ. of Tsukuba 38 43-58, 2015 43 The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia: Tajikistan Zubaidullo UBAIDULLOEV * Abstract Tajik people have a rich and old traditions of sports. The traditional sports and games of Tajik people, which from ancient times survived till our modern times, are: archery, jogging, jumping, wrestling, horse race, chavgon (equestrian polo), buzkashi, chess, nard (backgammon), etc. The article begins with an introduction observing the Tajik people, their history, origin and hardships to keep their culture, due to several foreign invasions. The article consists of sections Running, Jumping, Lance Throwing, Archery, Wrestling, Buzkashi, Chavgon, Chess, Nard (Backgammon) and Conclusion. In each section, the author tries to analyze the origin, history and characteristics of each game refering to ancient and old Persian literature. Traditional sports of Tajik people contribute as the symbol and identity of Persian culture at one hand, and at another, as the combination and synthesis of the Persian and Central Asian cultures. Central Asia has a rich history of the traditional sports and games, and significantly contributed to the sports world as the birthplace of many modern sports and games, such as polo, wrestling, chess etc. Unfortunately, this theme has not been yet studied academically and internationally in modern times. Few sources and materials are available in Russian, English and Central Asian languages, including Tajiki. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected];