Arash Zeini 8Th May 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gènes Et Mythes Littéraires : Pour Un Modèle Biologique Du Dynamisme Mythique

G`eneset mythes litt´eraires: pour un mod`elebiologique du dynamisme mythique Abolghasem Ghiasizarch To cite this version: Abolghasem Ghiasizarch. G`eneset mythes litt´eraires: pour un mod`elebiologique du dy- namisme mythique. Litt´eratures. Universit´eGrenoble Alpes, 2011. Fran¸cais. <NNT : 2011GRENL001>. <tel-00596834> HAL Id: tel-00596834 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00596834 Submitted on 30 May 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE GRENOBLE Spécialité : Imaginaire Arrêté ministériel : 7 août 2006 Présentée par « Abol Ghasem / GHIASIZARCH » Thèse dirigée par « Philippe / WALTER » préparée au sein du Laboratoire CRI – Centre de Recherche sur l’Imaginaire (EA 610) dans l'École Doctorale Langues, Littératures et Sciences Humaines GÈNES ET MYTHES LITTÉRAIRES : POUR UN MODÈLE BIOLOGIQUE DU DYNAMISME MYTHIQUE Thèse soutenue publiquement le « 14 janvier 2011», devant le jury composé de : M. Jean Bruno RENARD Professeur à l’Université Montpellier 3, Président M. Claude THOMASSET Professeur à l’Université Paris IV Sorbonne, Rapporteur M. Philippe WALTER Professeur à l’Université Grenoble 3, Membre GÈNES ET MYTHES LITTÉRAIRES : POUR UN MODÈLE BIOLOGIQUE DU DYNAMISME MYTHIQUE 2 REMERCIEMENT Qui ne remercie pas le peuple, ne remercie pas Dieu non plus. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected]; -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

Why Was the Story of Arash-I Kamangir Excluded from the Shahnameh?” Iran Nameh, 29:2 (Summer 2014), 42-63

Saghi Gazerani, “Why Was the Story of Arash-i Kamangir Excluded from the Shahnameh?” Iran Nameh, 29:2 (Summer 2014), 42-63. Why Was the Story of Arash-i Kamangir Excluded from the Shahnameh?* Saghi Gazerani Independent Scholar In contemporary Iranian culture, the legendary figure of Arash-i Kamangir, or Arash the Archer, is known and celebrated as the national hero par excellence. After all, he is willing to lay down his life by infusing his arrow with his life force in order to restore territories usurped by Iran’s enemy. As the legend goes, he does so in order to have the arrow move to the farthest point possible for the stretch of land over which the arrow flies shall be included in Iranshahr proper. The story without a doubt was popular for many centuries, but during the various upheavals of the twentieth century, the story of Arash the Archer was invoked, and in the hands of artists with various political leanings his figure was imbued with layers reflecting the respective artist’s ideological presuppositions.1 The most famous of modern renditions of Arash’s legend is Siavash Kasra’i’s narrative poem named after its protagonist. An excerpt of Kasra’i’s rendition of Arash’s story *For further discussion of this issue please see my ture,” www.iranicaonline.org (accessed March 3, forthcoming work, On the Margins of Historiog- 2014). Arash continues to make his appearance; raphy: The Sistani Cycle of Epics and Iran’s Na- for a recent operatic performance of the legend, tional History (Leiden: Brill, 2014). -

Read the Introduction

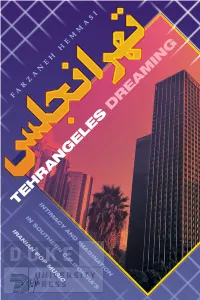

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

A History of Persian Literature Volume XVII Volumes of a History of Persian Literature

A History of Persian Literature Volume XVII Volumes of A History of Persian Literature I General Introduction to Persian Literature II Persian Poetry in the Classical Era, 800–1500 Panegyrics (qaside), Short Lyrics (ghazal); Quatrains (robâ’i) III Persian Poetry in the Classical Era, 800–1500 Narrative Poems in Couplet form (mathnavis); Strophic Poems; Occasional Poems (qat’e); Satirical and Invective poetry; shahrâshub IV Heroic Epic The Shahnameh and its Legacy V Persian Prose VI Religious and Mystical Literature VII Persian Poetry, 1500–1900 From the Safavids to the Dawn of the Constitutional Movement VIII Persian Poetry from outside Iran The Indian Subcontinent, Anatolia, Central Asia after Timur IX Persian Prose from outside Iran The Indian Subcontinent, Anatolia, Central Asia after Timur X Persian Historiography XI Literature of the early Twentieth Century From the Constitutional Period to Reza Shah XII Modern Persian Poetry, 1940 to the Present Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan XIII Modern Fiction and Drama XIV Biographies of the Poets and Writers of the Classical Period XV Biographies of the Poets and Writers of the Modern Period; Literary Terms XVI General Index Companion Volumes to A History of Persian Literature: XVII Companion Volume I: The Literature of Pre- Islamic Iran XVIII Companion Volume II: Literature in Iranian Languages other than Persian Kurdish, Pashto, Balochi, Ossetic; Persian and Tajik Oral Literatures A HistorY of Persian LiteratUre General Editor – Ehsan Yarshater Volume XVII The Literature of Pre-Islamic Iran Companion Volume I to A History of Persian Literature Edited by Ronald E. Emmerick & Maria Macuch Sponsored by Persian Heritage Foundation (New York) & Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University Published in 2009 by I. -

A History of Ottoman Poetry

351 whose works, if read aloud, would have been incomprehen- sible to all but a very few of their contemporaries. The moment that poetry became anything beyond a toy it had to go, as the Khayriyya of Nabi can bear witness. Even as the conventional idiom of a literary coterie, it contained within itself the elements of decay; there was ever present from the beginning the danger which eventually proved fatal, that the Persian embroidery should encroach too much upon the Turkish background, and should eventually cover and conceal this altogether. When this happened, as we have seen it did at the close of the Classic Age, there was nothing left but to set about undoing the work which it had taken all these centuries to complete. If we look upon the history of the Archaic and Classic Periods as that of the gradual I building up and development of this artificial Perso-Turkish literary idiom, we may regard the history of the Transition and Modern Schools as that of its gradual demolition and decline. I have spoken of the language, but it is the same with the spirit which therein found expression. The spirit of Perso- Turkish poetry had no true Hfe; its semblance of life was but a series of changes reflected from a foreign literature in a foreign land. It may imlccd \)v. that llicsi: clKiiiges ui-re n(jt altogether the result of deliberate imitation on the part of (li<- 'Osnianli poets; it is possible that the Zeitgeist that was al work in Persia passed in ilue course over Turkey loo, ;iiid th.it (ril.iin ideas successively lilliil the intellectual air in eitliei (onnliw I'ut sufli is no| the opinion ol the 'links Iheinsc-lves; and thr. -

The Impact of the Modernity Discourse on Persian Fiction

The Impact of the Modernity Discourse on Persian Fiction Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Comparative Studies in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Saeed Honarmand, M.A. Graduate Program in Comparative Studies The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Richard Davis, Advisor Margaret Mills Philip Armstrong Copyright by Saeed Honarmand 2011 Abstract Modern Persian literature has created a number of remarkable works that have had great influence on most middle class people in Iran. Further, it has had representation of individuals in a political context. Coming out of a political and discursive break in the late nineteenth century, modern literature began to adopt European genres, styles and techniques. Avoiding the traditional discourses, then, became one of the primary characteristics of modern Persian literature; as such, it became closely tied to political ideologies. Remarking itself by the political agendas, modern literature in Iran hence became less an artistic source of expression and more as an interpretation of political situations. Moreover, engaging with the political discourse caused the literature to disconnect itself from old discourses, namely Islamism and nationalism, and from people with dissimilar beliefs. Disconnectedness was already part of Iranian culture, politics, discourses and, therefore, literature. However, instead of helping society to create a meta-narrative that would embrace all discourses within one national image, modern literature produced more gaps. Historically, there had been three literary movements before the modernization process began in the late nineteenth century. Each of these movements had its own separate discourse and historiography, failing altogether to provide people ii with one single image of a nation. -

Historical, Mythical and Religious Narratives of the Babylonian Talmud

Historical, Mythical and Religious Narratives of the Babylonian Talmud in their Middle Persian Context Azadeh Ehsani Chombeli A Thesis In the Department Of Religions and Cultures Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2018 © Azadeh Ehsani Chombeli, 2018 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Azadeh Ehsani Chombeli Entitled: Historical, Mythical and Religious Narratives of the Babylonian Talmud in their Middle Persian Context and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Marguerite Mendell _____________________________________________External Examiner Dr. Touraj Daryaee _____________________________________________External to Program Dr. Ivana Djordjevic _____________________________________________Examiner Dr. Naftali Cohn _____________________________________________Examiner Dr. Mark Hale _____________________________________________Thesis Supervisor Dr. Richard Foltz Approved by __________________________________________________________ Dr. Leslie Orr, Graduate Program Director Tuesday, June 26, 2018 Dr. André Roy, Dean Faculty of Arts and Science ABSTRACT Historical, Mythical and Religious Narratives of the Babylonian Talmud in their -

Hillenbrand 2018 Iran Radpis

Carole Hillenbrand, Professorial Fellow, School of Medieval History, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK Robert Hillenbrand, Professorial Fellow, School of Art History, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK ABSTRACT This article presents the first full English translation of the Arabic text of that portion of Rashid al-Din’s Jami‘ al-Tawarikh (“World History”) which deals with five of the earliest Pishdadian or mythical kings of Iran. This text has a particular importance in that it dates from the lifetime of the author. Its content is distinctively different from that of the much longer and better-known narrative of Firdausi that deals with these monarchs. It is thus a reminder of the co-existence of several versions of this material. Alongside a brief commentary on the text itself, the article considers the role and content of the four paintings that accompany it, focusing on how they interpret the accompanying text, their storytelling techniques, their evocation of the Ilkhanate court and how far they presage future developments in Iranian painting. ANCIENT IRANIAN KINGS IN THE WORLD HISTORY OF RASHID AL-DIN Carole and Robert Hillenbrand Four of the most celebrated ancient kings of Iran make a perfunctory and somewhat unexpected appearance in the pictorial cycle of the Edinburgh fragment of the Jami‘ al- Tawarikh or World History of Rashid al-Din (d.1318), produced in Tabriz, the Mongol 1 capital of Iran, in the lifetime of the author.i The relevant text, with its accompanying images, comes almost at the beginning of the manuscript in its present truncated form – for the volume lacks both a frontispiece and the appropriate introductory matter.