Musicalization in Qualified Media of Poetry and Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gènes Et Mythes Littéraires : Pour Un Modèle Biologique Du Dynamisme Mythique

G`eneset mythes litt´eraires: pour un mod`elebiologique du dynamisme mythique Abolghasem Ghiasizarch To cite this version: Abolghasem Ghiasizarch. G`eneset mythes litt´eraires: pour un mod`elebiologique du dy- namisme mythique. Litt´eratures. Universit´eGrenoble Alpes, 2011. Fran¸cais. <NNT : 2011GRENL001>. <tel-00596834> HAL Id: tel-00596834 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00596834 Submitted on 30 May 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE GRENOBLE Spécialité : Imaginaire Arrêté ministériel : 7 août 2006 Présentée par « Abol Ghasem / GHIASIZARCH » Thèse dirigée par « Philippe / WALTER » préparée au sein du Laboratoire CRI – Centre de Recherche sur l’Imaginaire (EA 610) dans l'École Doctorale Langues, Littératures et Sciences Humaines GÈNES ET MYTHES LITTÉRAIRES : POUR UN MODÈLE BIOLOGIQUE DU DYNAMISME MYTHIQUE Thèse soutenue publiquement le « 14 janvier 2011», devant le jury composé de : M. Jean Bruno RENARD Professeur à l’Université Montpellier 3, Président M. Claude THOMASSET Professeur à l’Université Paris IV Sorbonne, Rapporteur M. Philippe WALTER Professeur à l’Université Grenoble 3, Membre GÈNES ET MYTHES LITTÉRAIRES : POUR UN MODÈLE BIOLOGIQUE DU DYNAMISME MYTHIQUE 2 REMERCIEMENT Qui ne remercie pas le peuple, ne remercie pas Dieu non plus. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and Dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract

Date:12/1/18 A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and Homer's Iliad are among the first literary masterpieces of Iran and Greece. These teachings include the educational teachings of Zal and Roudabeh, and Paris and Helen. This paper presents a comparative look at the immortal effect of this Iranian poet with Homer's poem-- the Greek blind poet. In this comparison, using a content analysis method, the effects of the educational teachings of these two stories are extracted and expressed, The results of this study show that the human and universal educational teachings of Shahnameh are far more than that of Homer's Iliad. Keywords: teachings, education,analysis,Shahname,Iliad. Introduction The literature of every nation is a mirror of the entirety of thought, culture and customs of that nation, which can be expressed in elegance and artistic delicacy in many different ways. Shahnameh and Iliad both represent the literature of the two peoples of Iran and Greece, which contain moral values for the happiness of the individual and society. "The most obvious points of Shahnameh are its advice and many examples and moral commands. To do this, Ferdowsi has taken every opportunity and has made every event an excuse. Even kings and warriors are used for this purpose. "Comparative literature is also an important foundation for the exodus of indigenous literature from isolation, and it will be a part of the entire literary heritage of the world, exposed to thoughts and ideas, and is also capable of helping to identify contemplation legacies in the understanding and friendship of the various nations."(Ghanimi, 44: 1994) Epic literature includes poems that have a spiritual aspect, not an individual one. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

Persian 2704 SP15.Pdf

Attention! This is a representative syllabus. The syllabus for the course you are enrolled in will likely be different. Please refer to your instructor’s syllabus for more information on specific requirements for a given semester. THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Persian 2704 Introduction to Persian Epic Instructor: Office Hours: Office: Email: No laptops, phones, or other mobile devices may be used in class. This course is about the Persian Book of Kings, Shahnameh, of the Persian poet Abulqasim Firdawsi. The Persian Book of Kings combines mythical themes and historical narratives of Iran into a mytho-historical narrative, which has served as a source of national and imperial consciousness over centuries. At the same time, it is considered one of the finest specimen of Classical Persian literature and one of the world's great epic tragedies. It has had an immense presence in the historical memory and political culture of various societies from Medieval to Modern, in Iran, India, Central Asia, and the Ottoman Empire. Yet a third aspect of this monumental piece of world literature is its presence in popular story telling tradition and mixing with folk tales. As such, a millennium after its composition, it remains fresh and rife in cultural circles. We will pursue all of those lines in this course, as a comprehensive introduction to the text and tradition. Specifically, we will discuss the following in detail: • The creation of Shahname in its historical context • The myth and the imperial image in the Shahname • Shahname as a cornerstone of “Iranian” identity. COURSE MATERIAL: • Shahname is available in English translation. -

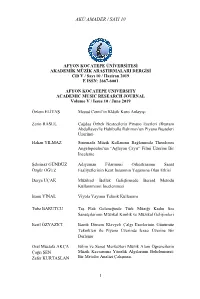

Akü Amader / Sayi 10 1

AKÜ AMADER / SAYI 10 AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ AKADEMİK MÜZİK ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ Cilt V / Sayı 10 / Haziran 2019 E ISSN: 2667-6001 AFYON KOCATEPE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC MUSIC RESEARCH JOURNAL Volume V / Issue 10 / June 2019 Özlem ELİTAŞ Mesud Cemil’in Klâsik Koro Anlayışı Zerin RASUL Çağdaş Özbek Bestecilerin Piyano Eserleri (Rustam Abdullayev'le Habibulla Rahimov'un Piyano Besteleri Üzerine) Hakan YILMAZ Sinemada Müzik Kullanımı Bağlamında Theodoros Angelopoulos’un “Ağlayan Çayır” Filmi Üzerine Bir İnceleme Şehrinaz GÜNDÜZ Adıyaman Filarmoni Orkestrasının Sanat Özgür OĞUZ Faaliyetlerinin Kent İnsanının Yaşamına Olan Etkisi Derya UÇAK Müziksel Bellek Geliştirmede Berard Metodu Kullanımının İncelenmesi Banu YİNAL Viyola Yayının Teknik Kullanımı Tuba BARUTCU Taş Plak Geleneğinde Türk Müziği Kadın Ses Sanatçılarının Müzikal Kimlik ve Müzikal Gelişimleri Beril ÖZYAZICI Barok Dönem Klavyeli Çalgı Eserlerinin Günümüz Teknikleri ile Piyano Üzerinde İcrası Üzerine Bir Derleme Oral Mustafa AKÇA Bilim ve Sanat Merkezleri Müzik Alanı Öğrencilerin Çağrı ŞEN Müzik Kavramına Yönelik Algılarının Belirlenmesi: Zafer KURTASLAN Bir Metafor Analizi Çalışması 1 AKÜ AMADER / SAYI 10 AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ AKADEMİK MÜZİK ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ Cilt V / Sayı 10 / Haziran 2019 E ISSN: 2667-6001 AFYON KOCATEPE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC MUSIC RESEARCH JOURNAL Volume V / Issue 10 / June 2019 Sahibi / Owner Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi adına Devlet Konservatuvarı Müdürü Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Editörler / Editors Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Duygu SÖKEZOĞLU ATILGAN Yardımcı Editörler / Co-Editorials Doç. Çağhan ADAR Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Safiye YAĞCI Öğr. Elm. Filiz YILDIZ Yayın Kurulu / Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Prof. Dr. Emel Funda TÜRKMEN Doç. Çağhan ADAR Doç. Servet YAŞAR Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Duygu SÖKEZOĞLU ATILGAN Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Sevgi TAŞ Dr. -

Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War Against Stronger States?

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2004 Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War against Stronger States? Sang Hyun Park University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Park, Sang Hyun, "Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War against Stronger States?. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2346 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sang Hyun Park entitled "Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War against Stronger States?." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Robert A. Gorman, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Mary Caprioli, Donald W. Hastings, April Morgan, Anthony J. Nownes Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sang-Hyun Park entitled “Cognitive Theory of War: Why Do Weak States Choose War against Stronger States?” I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. -

Arash Zeini 8Th May 2020

Response to ‘Next steps on Book Pahlavi’ (L2/20-135) Arash Zeini 8th May 2020 Introduction Pournader & Hai (2020) might be right in saying that ‘Book Pahlavi may be the best-known complex script not yet encoded in Unicode’. However, I am inclined to add that Book Pahlavi is certainly one of the least researched and understood scripts of late antiquity. Much work is needed before we can make reliable statements about the palaeography of Book Pahlavi. The issues that have puzzled the Unicode experts are in part genuinely difficult to answer. But in my view, the wrong questions have also been asked at times.1 In this document I will attempt to answer the questions raised by Pournader & Hai (2020) which is a very welcome addition to the proposals as it consolidates the questions that have remained unanswered. Please note that my rendering of Middle Persian words and Pahlavi characters is limited by the possibilities offered by the available fonts, which are not designed to accurately represent the scribal idiosyncrasies. If any representations raise more questions, please contact me for clarifications. Question 1 yh/1: The MP suffix -īh, transliterated <-yh>, is written / in Book Pahlavi. Contrary to Meyers (2014:12), the correct analysis of / is ! + + or $ + -. Some- times the scribes abbreviate or rather simplify this sequence of characters to . This happens most commonly at the end of the line, and not in everymanu- script. It is, for instance, very rare in manuscripts of the Pahlavi Yasna. Meyers 1See, for instance, Pournader & Hai (2020:6) on the issue of <b> as raised by Meyers (2014). -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected]; -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

Research Analysis in Eclectic Theory (Kaboudan and Sfandiar)

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering Vol:8, No:7, 2014 Research Analysis in Eclectic Theory (Kaboudan and Sfandiar) Farideh Alizadeh, Mohd Nasir Hashim 8- Western-influenced theatre and 9- Eclectic theatre [3]. In Abstract—Present research investigates eclecticism in Iranian the current study, researcher attempts to investigate Kaboudan theatre on the basis of eclectic theory. Eclectic theatre is a new theory and Sfandiar as a kind of Iranian contemporary theatre on the in postmodernism. The theory appeared during 60th – 70th century in basis of and relying on eclectic theatre. The present research some theatres such as “Conference of the Birds”. objective is to review the eclectic theater in Iranian current Special theatrical forms have been developed in many geographical- cultural areas of the world and are indigenous to that theater. area. These forms, as compared with original forms, are considered to be traditional while being comprehensive, the form is considered to II. SUMMARY OF THE STORY be national. Kaboudan and Sfandiar theatre has been influenced by Upon Garzam1 trick (one of the king companions), Sfandiar elements of traditional form of Iran. is charged to overthrow Goshtaseb ruling. Goshtaseb (the king) asks others to help, but all are talking about Sfandiar Keywords—Eclectic theatre, theatrical forms, tradition, play. conspiracy at night and capturing Bactria. Then, upon I. INTRODUCTION Goshtaseb order and in front of Sfandiar, children breaks his wing. Like mocking players they send him far from the palace EW approach of Critical Theories in Eclectic Theatre has and imprison him in Gonbadan castle.