Re(Art)Iculating Empowerment: Cooperative Explorations with Community Development Workers in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

Barbara Lorson

COMPARISON OF NEONATAL OUTCOMES IN MATERNAL USERS AND NON-USERS OF HERBAL SUPPLEMENTS A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Holly A Larson, B.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Master‟s Examination Committee: Dr. Maureen Geraghty, Advisor Approved by Annette Haban Bartz ______________________________ Dr. Christopher A. Taylor Advisor Graduate Program in Allied Medical Professions COMPARISON OF NEONATAL OUTCOMES IN MATERNAL USERS AND NON-USERS OF HERBAL SUPPLEMENTS By Holly A. Larson, M.S. The Ohio State University, 2008 Dr. Maureen Geraghty, Advisor This pilot study was a retrospective chart review. The purposes of this study were to describe the prevalence herbal supplement use, to identify characteristics linked to increased herbal supplement use and, to identify adverse outcomes linked to herbal supplement use. Rate of use in the study sample of 2136 charts was 1.1% and identified 17 supplements. The most common supplements identified were teas. Characteristics of the neonates and controls were analyzed as appropriate and revealed no statistical significance. Characteristics of the mothers also revealed no statistical difference. There was a statistically significant difference between herbal users and herbal non-users and the trimester prenatal care began. Neonatal outcomes were statistically different on two measures. Further study is needed to be able to make recommendations regarding safety and efficacy of herbal supplements as well as to be able to better understand motives for choosing to use them. ii Dedicated to the Mama and the Daddy Bears iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my advisor, Dr. -

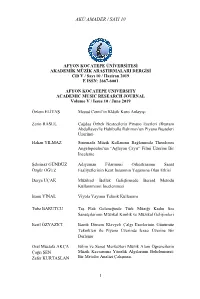

Akü Amader / Sayi 10 1

AKÜ AMADER / SAYI 10 AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ AKADEMİK MÜZİK ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ Cilt V / Sayı 10 / Haziran 2019 E ISSN: 2667-6001 AFYON KOCATEPE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC MUSIC RESEARCH JOURNAL Volume V / Issue 10 / June 2019 Özlem ELİTAŞ Mesud Cemil’in Klâsik Koro Anlayışı Zerin RASUL Çağdaş Özbek Bestecilerin Piyano Eserleri (Rustam Abdullayev'le Habibulla Rahimov'un Piyano Besteleri Üzerine) Hakan YILMAZ Sinemada Müzik Kullanımı Bağlamında Theodoros Angelopoulos’un “Ağlayan Çayır” Filmi Üzerine Bir İnceleme Şehrinaz GÜNDÜZ Adıyaman Filarmoni Orkestrasının Sanat Özgür OĞUZ Faaliyetlerinin Kent İnsanının Yaşamına Olan Etkisi Derya UÇAK Müziksel Bellek Geliştirmede Berard Metodu Kullanımının İncelenmesi Banu YİNAL Viyola Yayının Teknik Kullanımı Tuba BARUTCU Taş Plak Geleneğinde Türk Müziği Kadın Ses Sanatçılarının Müzikal Kimlik ve Müzikal Gelişimleri Beril ÖZYAZICI Barok Dönem Klavyeli Çalgı Eserlerinin Günümüz Teknikleri ile Piyano Üzerinde İcrası Üzerine Bir Derleme Oral Mustafa AKÇA Bilim ve Sanat Merkezleri Müzik Alanı Öğrencilerin Çağrı ŞEN Müzik Kavramına Yönelik Algılarının Belirlenmesi: Zafer KURTASLAN Bir Metafor Analizi Çalışması 1 AKÜ AMADER / SAYI 10 AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNİVERSİTESİ AKADEMİK MÜZİK ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ Cilt V / Sayı 10 / Haziran 2019 E ISSN: 2667-6001 AFYON KOCATEPE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC MUSIC RESEARCH JOURNAL Volume V / Issue 10 / June 2019 Sahibi / Owner Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi adına Devlet Konservatuvarı Müdürü Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Editörler / Editors Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Duygu SÖKEZOĞLU ATILGAN Yardımcı Editörler / Co-Editorials Doç. Çağhan ADAR Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Safiye YAĞCI Öğr. Elm. Filiz YILDIZ Yayın Kurulu / Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Uğur TÜRKMEN Prof. Dr. Emel Funda TÜRKMEN Doç. Çağhan ADAR Doç. Servet YAŞAR Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Duygu SÖKEZOĞLU ATILGAN Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Sevgi TAŞ Dr. -

Noodle Soup Bubble Milk Tea $3.50 Hot Milk Tea $3.00 (Served Cold Or Warm) ** Beef Stew Noodle Soup $10.00 Black Tea Chocolate Honeydew

Noodle Soup Bubble Milk Tea $3.50 Hot Milk Tea $3.00 (served cold or warm) ** Beef Stew Noodle Soup $10.00 Black Tea Chocolate Honeydew ** Curry Chicken Noodle Soup $9.00 Black Tea Chocolate Coconut Green Tea Almond Thai Tea ** Curry Tofu Noodle Soup * $8.75 Green Tea Almond Honeydew Strawberry Mango Coconut Minced Pork Noodle Soup $7.50 Strawberry Mango Green Apple Green Apple Taro Watermelon Wonton Noodle Soup $8.50 Papaya Watermelon Thai Tea Taro Vegetable Noodle Soup $7.50 Lo Mein Noodle Slush (Icees) $4.00 Hot Ginger Milk Tea $3.25 Minced Pork Sauce w/ Noodle $7.50 Strawberry Kiwi Pineapple Ginger Milk Tea Ginger Almond Milk Tea Mix Vegetable w/ Cellophane Noodle * $7.50 Green Apple Orange Mango Ginger Green Milk Tea Ginger Coconut Milk Tea ** Curry Chicken w/ Noodle $9.00 Passionfruit Lemon Peach Ginger Chocolate Milk Tea ** Curry Tofu w/ Noodle * $8.75 Pomegranate Lychee Cherry (Create your own, mix 2 flavors) Beef Stew w/ Noodle $10.00 Flavored Ice Tea $2.75 (choose Green Tea or Black Tea) ** Spicy Pan Fried Ramen $7.75 Strawberry Kiwi Peach Pomegranate Rice Fruit Shake (Smoothies) $4.25 Green Apple Orange Pineapple Lychee ** Curry Chicken Over Rice $8.50 Strawberry Kiwi Pineapple Passionfruit Lemon Mango Cherry ** Curry Tofu Over Rice * $7.50 Green Apple Orange Mango House Tea Beef Stew Over Rice $9.00 Passionfruit Lemon Peach Ice Black Tea………$2.00 Hot Black Tea……. .$1.85 Minced Pork Sauce Over Rice $6.50 Pomegranate Lychee Cherry Ice Green Tea……..$2.00 Hot Green Tea…….$1.85 (Create your own, mix 2 flavors) Side Order Milk Shake -

W W W . K a B a B R O L L S . C

WWW.KABABROLLS.COM Your diet is a bank account. Good food choices are good investments. … Bethenny Frankel WWW.KABABROLLS.COM Your Menu Options now that’s what you call a comprehensive urban ‘Desi’ menu! WWW.KABABROLLS.COM Dahi Puri CHAATS & APPETIZERS (The ultimate appetizer/snack, packed Mix Chaat with rich texture and flavor) Pani Puri Serving Tradition Since 2005 Events are all about chat – communication and Papri Chaat togetherness. Why not ‘chaat and chat,' an excellent companion to go with your official or social gathering, which adds authenticity to the Sev Puri theme of the cuisine and is a great way to prep your taste buds for the coming feast. Bhel Puri Chana Chaat Dahi Aloo Chaat Meethi Puri WWW.KABABROLLS.COM Fruit Chaat CHAATS & APPETIZERS (The ultimate appetizer/snack, packed with rich texture and flavor) Serving Tradition Since 2005 & more… Mutton Shami Kabab Samosas (Chicken/Mutton/Aloo) Masala Fries WWW.KABABROLLS.COM Cream of Chicken SOUPS Cream of Tomato Serving Tradition Since 2005 Very popular in our winter menu, the soups we serve are tangy and spicy, and they are a perfect start to complement your dining event. WWW.KABABROLLS.COM Grilled Salad Charcoal grilled chicken over a bed of fresh mixed salad SALADS with our signature dressing Serving Tradition Since 2005 Garden Salad Lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers and carrots with our We are worthy of our salad offering too. Authentic signature dressing and an original twist added to them to make them all the better. You must make our grilled salad an inclusion to your menu, for all the ‘only salad’ Raita Salad guests joining your event. -

A Look at the History of Instrumental Performance

Turkish Journal of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation; 32(3) ISSN 2651-4451 | e-ISSN 2651-446X A LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF INSTRUMENTAL PERFORMANCE Haydarov Azizbek1, Talaboyev Azizjon2, Madaminov Siddiqjon3, Mamatov Jalolxon4 1,2,3,4Fergana Regional Branch of Uzbekistan State Institute of Arts and Culture [email protected], [email protected]. [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT This article tells about the emergence and development of Uzbek folk music and instrumental performance in Central Asia. There are many legends about the creation of musical instruments. One of such legends is cited by musicologist B.Matyokubov. According to the narrations, the instruments of Tanbur, Dutor, Nay, and Gijjak are the four angels may be due to their efforts, namely, the messenger angel Gabriel, the angel Michael who moves the world, the angel Isrofil who blows the trumpet in the Hereafter, and the angel of death in the body of Adam. According to musicians and craftsmen, they took mulberry wood from heaven to make instruments. From the above it can be concluded that our national instruments were formed before and during our era, and some of them still retain their appearance, albeit partially. Keywords: music, instrument, circle, tanbur, rubob, ud, melody. In the book of President Islam Karimov "High spirituality is an invincible force" The book proudly acknowledges the discovery of a bone flute along with gold and bronze objects in a woman's grave in the village of Muminabad near Samarkand, which has a unique musical culture in the Bronze Age. The circular circle-shaped instrument found in the Saymalitosh rock drawings on the Fergana mountain range and depicted among the participants of the ceremony is also believed to date back to the 2nd century BC. -

Tea Practices in Mongolia a Field of Female Power and Gendered Meanings

Gaby Bamana University of Wales Tea Practices in Mongolia A Field of Female Power and Gendered Meanings This article provides a description and analysis of tea practices in Mongolia that disclose features of female power and gendered meanings relevant in social and cultural processes. I suggest that women’s gendered experiences generate a differentiated power that they engage in social actions. Moreover, in tea practices women invoke meanings that are also differentiated by their gendered experience and the powerful position of meaning construction. Female power, female identity, and gendered meanings are distinctive in the complex whole of cultural and social processes in Mongolia. This article con- tributes to the understudied field of tea practices in a country that does not grow tea, yet whose inhabitants have turned this commodity into an icon of social and cultural processes in everyday life. keywords: female power—gendered meanings—tea practices—Mongolia— female identity Asian Ethnology Volume 74, Number 1 • 2015, 193–214 © Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture t the time this research was conducted, salty milk tea (süütei tsai; сүүтэй A цай) consumption was part of everyday life in Mongolia.1 Tea was an ordi- nary beverage whose most popular cultural relevance appeared to be the expres- sion of hospitality to guests and visitors. In this article, I endeavor to go beyond this commonplace knowledge and offer a careful observation and analysis of social practices—that I identify as tea practices—which use tea as a dominant symbol. In tea practices, people (women in most cases) construct and/or reappropri- ate the meaning of their gendered identity in social networks of power. -

High Chai the Thick Sweet Spiced Milk-Tea with a Subtle Burn at the Back of the Throat, Namely Chai, Is an Integral Part of the Rhythm of Life in India

High Chai The thick sweet spiced milk-tea with a subtle burn at the back of the throat, namely Chai, is an integral part of the rhythm of life in India. Tea is India’s most popular drink. Chai warms the heart and awakens the soul. The sweet and delicate, yet fiery, punch of its aromatic spices wafts through you as you sip and has you hooked in a heartbeat. It is made across the country, from the comfort of homes to scattered tiny tea stalls on road sides, right up to the splendour of the residences of the maharajas. Café Delhi introduces High Chai which evokes the rich traditions of the Indian chai culture, of sharing food and sipping chai. We have created an innovative twist on the traditional afternoon tea, marrying the Indian luxury with the tradition of British heritage. A beautiful selection of food has been exclusively crafted for this menu. Using traditional spices from across India, with a range of exotic tea blends such as, masala chai and kashmiri chai. 13.95 per person Pre-booking is required Namkeen chandni chowk samosa punjabi style samosas stuffed with spiced pea & potato, in a flaky & crisp pastry aubergine pakode deep fried in a spicy batter papdi chaat crisp flour pancake spheres, chickpeas, potatoes, yoghurt, mint & tamarind chutney dhokla steamed chickpea cake served with tamarind chutney malai soya soya pieces marinated in a natural yoghurt, garlic, cheese & ground masala paneer kati roll Indian cheese in a cumin infused yoghurt marinade rolled in a naan vada pav spiced potato fritter sandwiched between a pav (bun) meetha coconut gulab jamun Indian donuts soaked in a rose scented syrup, dusted with coconut flakes jalebi sugar syrup golden-coloured rings of deep-fried maida batter pistachio kheer traditional rice pudding finished with crushed pistachio This menu cannot be used in conjunction with any other menu per table. -

8 the Orpheus-Type Myth in Turkmen Musical Tradition Sławomira Żerańska-Kominek Institute of Musicology, University of Warsaw

8 The Orpheus-Type Myth in Turkmen Musical Tradition Sławomira Żerańska-Kominek Institute of Musicology, University of Warsaw Introduction Few figures from Greek mythology have played such a significant role in Eu- ropean culture. An heroic voyager into the underworld, the most faithful of lovers, a priest, the mutilated victim of female jealousy, a teacher of human- ity and an inventor, Orpheus was first and foremost a musician and poet, the embodiment of the artist. The countless reinterpretations of the ancient legend which have arisen over the centuries in the minds of musicians, philoso- phers, poets and painters have sought in the image of the Thracian singer the essence and the sense of artistic creativity, linked most closely to religious experience. The divine gift of music and poetry enable him to attain levels of consciousness that are inaccessible to ordinary humans and connect him to the supernatural world. As the ‘translator of the Gods’, the poet reveals to people spiritual truths, he is the conduit of sacred mysteries which are accessible to the chosen few alone. In sacrificing his life, Orpheus becomes the First Artist to transmit to future generations the secret of his art. The image of a mythical poet-musician who dies of love while seeking im- mortality in art is not the exclusive property of European culture. A remark- ably similar figure can be found in the tradition of the peoples of Central Asia. Görogly (Son of the Grave) is an initiated singer, a soulful poet, who, in tread- ing the path of love, vanquishes death, restores harmony to the universe and brings cultural goods to mankind. -

Loanwords in Uyghur in a Historical and Socio-Cultural Perspective (1), DOI: 10.46400/Uygur.712733 , Sayı: 2020/15, S

Uluslararası Uygur Araştırmaları Dergisi Sulaiman, Eset (2020). Loanwords in Uyghur in a Historical and Socio-Cultural Perspective (1), DOI: 10.46400/uygur.712733 , Sayı: 2020/15, s. 31-69. LOANWORDS IN UYGHUR IN A HISTORICAL AND SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE (1) [Araştırma Makalesi-Research Article] Eset SULAIMAN* Geliş Tarihi: 01.04.2020 Kabul Tarihi: 13.06.2020 Abstract Modern Uyghur is one of the Eastern Turkic languages which serves as the regional lingua franca and spoken by the Uyghur people living in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) of China, whose first language is not Mandarin Chinese. The number of native Uyghur speakers is currently estimated to be more than 12 million all over the world (Uyghur language is spoken by more than 11 million people in East Turkistan, the Uyghur homeland. It is also spoken by more than 300,000 people in Kazakhstan, and there are Uyghur-speaking communities in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, India, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Mongolia, Australia, Germany, the United States of America, Canada and other countries). The Old Uyghur language has a great number of loanwords adopted from different languages at different historical periods. The loanwords come from sources such as ancient Chinese, the ancient Eastern Iranian languages of Saka, Tocharian and Soghdian of the Tarim Basin. Medieval Uyghur, which developed from Old Uyghur and Karakhanid Turkic, is in contrast to Old Uyghur, is a language containing a substantial amount of Arabic and Persian lexical elements. Modern Uyghur was developed on the basis of Chaghatay Turki, which had also been heavily influenced by Arabic and Persian vocabularies. -

Winter Flavors

Choose your Choose your Choose your Step 1: Flavor Step 2: drink type Step 3: Topping All drinks include one toppoing Small: $3.50 Medium: $4.50 Large: $5.00 Slushie Iced Tea Almond* Green Apple Peach Tapioca Pearls Frozen Drink with Sweetened or Flavored Gummie Bear-like Texture. Avocado* Habanero Lime Pineapple any flavor. with any flavor. -Organic Green Soft and Gooey on the Outside, Sweet and Chewy on the inside. Banana Hibiscus Pistachio* Served over Ice. -Organic Black Chai* Honeydew* Raspberry -Organic Berried Treasure Popping Pearls OR Cheesecake* Lavender Rose Smoothie* Milk Tea A sweet fruit juice pearl that bursts with flavor when bitten into. Cherry Lemonade Strawberry Milk-based creamy Sweetened Black Tea Blueberry Mango Pomegranate Chocolate Lime Taro* frozen drink. and Milk. Cherry Orange Strawberry Cinnamon Bun* Lychee Thai Tea* *Contains Milk Milk and Iced Teas are served over ice. Green Apple Passion Fruit Vanilla Yogurt Coconut* Matcha* Vanilla* Lychee Peach Coffee* Mango Violet Or, get your drink hot! Cookies & Cream* Mint Watermelon Substitute Soy, Hemp, Coconut or Almond Milk +$1.00 OR Jellies Cotton Candy* Orange *contains milk Add Whipped Cream to Any Drink +$.50 Meat from a coconut soaked in jelly-like fruit juice. Cucumber Passion Fruit Unless otherwise specifed while ordering, Flavors Mango Stars Lychee Or mix any 2! containing milk are served as smoothies. Flavors not Strawberry Stars Coffee Sugar-Free: containing milk are served as slushies. Rainbow: Mango, Strawberry & Coconut Pomegranate, Wildberry Lemonade, -

Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics

Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics Rafis Abazov Greenwood Press CULTURE AND CUSTOMS OF THE CENTRAL ASIAN REPUBLICS The Central Asian Republics. Cartography by Bookcomp, Inc. Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics 4 RAFIS ABAZOV Culture and Customs of Asia Hanchao Lu, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abazov, Rafi s. Culture and customs of the Central Asian republics / Rafi s Abazov. p. cm. — (Culture and customs of Asia, ISSN 1097–0738) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–33656–3 (alk. paper) 1. Asia, Central—History. 2. Asia, Central—Social life and customs. I. Title. DK859.5.A18 2007 958—dc22 2006029553 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by Rafi s Abazov All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2006029553 ISBN: 0–313–33656–3 ISSN: 1097–0738 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Series Foreword vii Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Notes on Transliteration xvii Chronology xxi 1 Introduction: Land, People, and History 1 2 Thought and Religion 59 3 Folklore and Literature 79 4 Media and Cinema 105 5 Performing Arts 133 6 Visual Arts 163 7 Architecture 191 8 Gender, Courtship, and Marriage 213 9 Festivals, Fun, and Leisure 233 Glossary 257 Selected Bibliography 263 Index 279 Series Foreword Geographically, Asia encompasses the vast area from Suez, the Bosporus, and the Ural Mountains eastward to the Bering Sea and from this line southward to the Indonesian archipelago, an expanse that covers about 30 percent of our earth.